Abstract

Objectives: To clarify the correlation between the Japanese Aging Male Questionnaire (JAMQ) and the Aging Males’ Symptoms (AMS) scale through the factor analysis in Japanese male.

Materials and methods: In 61 male patients who visited the LOH outpatient clinic of Teikyo University Hospital, subjective symptoms featuring LOH were evaluated using the JAMQ and AMS. Factor analysis was performed on each questionnaire to clarify the LOH-related factors. Correlational analysis between the subscale scores representing such factors and the serum hormone profiles was also performed.

Results: Factor analysis of the JAMQ revealed an internal structure consisting of three subgroups: somatic, psychological and sexual factors with good categorization of the indicators to the appropriate subgroup. In contrast, the indicators of the AMS showed incomplete conformity to the subgroups of the JAMQ. Correlational analysis showed that each score on the JAMQ subgroups had the highest coefficient of correlation with the corresponding AMS subgroup (p < 0.001). There was no significant association between total and free serum testosterone levels and the total and subscale scores on either AMS or JAMQ.

Conclusions: The results of factor analysis suggest that the sexual perceptions of Japanese populations might differ from those of Caucasian populations. JAMQ would be useful to separately assess individual aspects of somatic, psychological and sexual symptoms related to LOH among Japanese males.

Introduction

Testosterone and its metabolites play a crucial role in the health and development of males. Decreased testosterone levels cause a range of symptoms including sexual dysfunction, cognitive impairment, decreased energy, depressed mood, increased fat mass, sarcopenia, anemia and reduced bone mineral density [Citation1]. Low testosterone levels can also have an impact on physical, social, emotional, cognitive and sexual functioning [Citation2], all of which are key components of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [Citation3]. In the case of male hypogonadism, decreased energy levels and impaired sexual performance appear to be the most important QOL issues. The negative impact of hypogonadism on sexual function, energy level, body composition, mood and cognitive function is likely to have an adverse effect on QOL.

Late onset hypogonadism (LOH) is a clinical and biochemical syndrome associated with advancing age. It is characterized by the presence of any of the typical signs or symptoms of LOH listed above and a deficiency in serum testosterone levels [Citation4–6]. Patients with LOH complaint about somatic, psychological and sexual symptoms such as increase in visceral fat, decrease in muscle volume and strength, change in mood, fatigue, depressed mood and decreased sexual functions. Many of these symptoms are similar to those associated with female menopause and depression [Citation7]. LOH becomes a target of treatment when the clinical symptoms are related to a reduction in testosterone levels. Thus, the qualitative and quantitative evaluation of symptoms of LOH by screening questionnaires is essential to determining the severity of the syndrome. Furthermore, such questionnaires are useful for evaluating the efficacy of treatment.

The Aging Males’ Symptoms (AMS) scale is a self-rating questionnaire that was originally developed and validated in a German database, that is, predominantly Caucasian. It consists of 17 items of psychological, somatic and sexual symptoms. It has been used worldwide to evaluate the severity of symptoms of LOH [Citation8–10]. It also has been shown to be effective for evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of testosterone replacement therapy in the treatment of LOH [Citation11]. It is the most frequently used tool for measuring HRQOL in aging males [Citation12]. The scale was designed and standardized as a self-administered questionnaire to (1) assess symptoms of aging (independent from those which are disease-related) between groups of males under different conditions, (2) evaluate the severity of symptoms over time and (3) measure changes pre- and post-androgen replacement therapy.

The scale began as a listing of symptoms/complaints and a comparison of more than 200 variables in more than 100 medically well-characterized males. During recent years, international research has contributed to the development of the AMS scale as a patient-reported outcome scale used in clinical studies in all age groups of men. Furthermore, the AMS scale is well accepted internationally and is available in 21 languages [Citation9]. Indeed, comparison of the internal structure of the German sample against samples from other countries shows a high degree of similarity, with a few notable exceptions. In the Asian samples, three out of five items intended to categorize in the psychological factor subgroup seem to associate more with the somatic subgroup. This finding suggests that the individual domain scores of the AMS are not fully independent in the Asian samples.

Kumamoto et al. conducted a community-based study (n > 1000) on quality of life (QOL) in healthy men and women between age 30 and 60, using a questionnaire that included items on mental and neurological symptoms, symptoms related to cardiovascular disorders, symptoms related to locomotive disorders, perceptual disorders and symptoms of sexual functions [Citation11,Citation13]. Using this questionnaire as a starting point, we developed the Japanese Aging Male Questionnaire (JAMQ) consisting of 18 questions (). The JAMQ was specifically designed to overcome the aberrant factorization of sexual perceptions among Japanese subjects taking the AMS. This scale has three dimensions of symptoms/complaints: psychological factors, somatic factors and sexual and urinary factors.

Table 1. JAMQ.

The purpose of this study was to assess the correlation between JAMQ and the AMS in Japanese male to demonstrate the usefulness of the JAMQ for clinical application. To complete our research task, factor analysis of the AMS and JAMQ was carried out individually to compare the effectiveness of each tool in assessing LOH. Our particular interest was to determine how clearly each questionnaire reflected the three subgroups of symptoms (psychological, somatic and sexual) identified by the factor analysis.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The subjects of this research were 61 patients who self-referred for symptoms of LOH either to the Men’s Health Clinic of Teikyo University Hospital, Tokyo, or its related facilities. This study was reviewed by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Teikyo University, and all subjects gave their informed consent prior to being included in the study.

Methods

At the time of first visit, subjective symptoms were evaluated using the AMS and JAMQ questionnaires. Blood samples were collected between 9:00 and 11:00 am. Total and free serum testosterone levels were measured as part of the endocrinological examination.

shows the items in JAMQ translated into English. (The English version of JAMQ has not yet been validated.) The JAMQ has 18 items and the first 17 are structured such that the individual subject can score the intensity of the symptoms on an ordinal scale of 1 to 4, that is, 1 stands for “almost none”, 2 for “moderate”, 3 for “severe” and 4 for “very severe”. Only question 18 is differently structured to assess the frequency of sexual intercourse. Consequently, item 18 was excluded from the analysis when calculating the total scores [Citation9]. shows the items in the AMS. Each item has five degrees of severity of symptoms [Citation8–10].

Table 2. AMS Questionnaire.

Data analysis

The analyses were performed using the SAS statistical package (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). A p value of less than 0.05, two-tailed, was considered statistically significant. First, a factor analysis was conducted to independently determine the structure of AMS items versus the JAMQ items. Common factors were extracted from the items by factor analysis (principal component analysis) provided that each eigenvalue was greater than 1.0. Eigenvalues measure the amount of variation in the total sample accounted for by each factor. If a factor has a low eigenvalue, then it is contributing little to the explanation of variances in the variables and may be disregarded as being redundant with more important factors. The common factor axes were rotated by the varimax method to show the distinct nature of each factor. These methods are standardized and commonly used in studies involving factor analysis [Citation14,Citation15]. Second, correlational analysis was performed between the individual item scores of each factor of AMS and JAMQ, respectively. Finally, correlational analysis was also performed between the scores obtained on the AMS and JAMQ and serum levels of total and free testosterone.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

shows the patients’ characteristics. Thirty-two subjects were under 50, 24 subjects were between 50 and 64, and 4 subjects were older than 65 years of age. The median values of total and free serum testosterone were 367.7 ng/dl and 12.1 pg/ml, respectively; no significant differences in these levels were found among the different age groups. The median scores of total JAMQ were 35, whereas those of the total AMS score were 46. No significant differences in scoring were found between the different age groups.

Table 3. Patients’ characteristics.

Factor analysis of the questionnaires

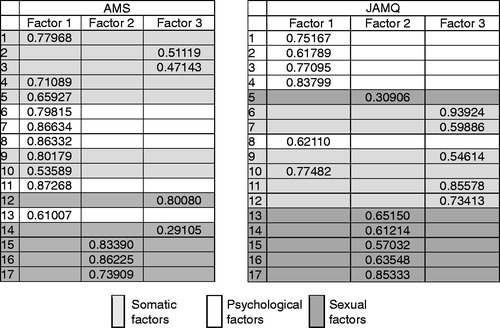

Five factors had eigenvalues of more than 1 in both the AMS and the JAMQ. Concerning AMS, the eigenvalues for the first through fifth factors were 7.46, 2.12, 1.32, 1.12 and 1.08, respectively. Concerning JAMQ, they were 6.73, 1.76, 1.35, 1.17 and 1.07, respectively. Factor analysis was then performed setting the significant number of factors to 3, because AMS is usually divided into three categories, namely, somatic, psychological and sexual, and because the effectiveness of doing so was confirmed in a previous study [Citation16]. shows the results of this analysis. The cumulative proportion rates of the three factors were 77% for AMS and 58% for JAMQ. The numbers shown are the highest factor loadings for each of the questions. In the original AMS, questions 1 through 5, and 9 through 10 were classified as somatic factors, but questions 2 and 3 were classified separately into Factor 3 in this study. The questions originally categorized as psychological factors, questions 6 through 8, 11 and 13 were all classified into Factor 1 together with the somatic factors. The questions originally categorized as sexual factors, questions 12 and 14 through 17 were partly classified into Factor 2 (questions 15 through 17) and partly into Factor 3 (questions 12 and 14) in this study.

When AMS was applied to the subjects in the present study, the three subgroups proposed by Heinemann [Citation8] did not fit well. On the other hand, in JAMQ, when Factor 1 was considered psychological, Factor 2 as sexual, and Factor 3 as somatic, it matched very well with the content of the questions. However, question 10 “Have headaches, feel heavy-headed and suffer from stiff shoulders” was classified as Factor 1, although the question was originally intended to reflect somatic symptoms. The reason for this discrepancy is addressed in the discussion, and we finally divided JAMQ into the three subgroups as shown in .

Table 4. Subgroups of JAMQ.

Correlational analysis of the questionnaires

shows the results of the correlational analyses between the AMS and JAMQ scores. Each score on the three factor items had the highest coefficient of correlation with that of corresponding factors in the other scale (p < 0.001). The correlation analysis showed the significant variation in the coefficient of correlation between AMS and JAMQ. For example, sexual domain in AMS had the highest coefficient with psychological domain in JAMQ. shows the results of correlation analysis between biological parameters (i.e. total and free serum testosterone levels) and the response to questionnaires (i.e. the AMS and JAMQ scores). There were no significant associations between the biological parameters and the total scores of AMS and JAMQ or with the scores of each factor of AMS and JAMQ.

Table 5. Coefficient of correlation between the JAMQ and AMS scores.

Table 6. Correlation of JAMQ and AMS scores with the levels of sexual hormones.

Discussion

This study supports the prevalent 3-factor model of LOH, namely, somatic, psychological and sexual [Citation7,Citation17–23]. In this regard, JAMQ conformed better with the pre-existing model than the AMS in Japanese subjects. The AMS was presented for the first time in 1999 by Heinemann [Citation8]. Subsequently, this questionnaire was translated into various languages, including Japanese, and its validity was tested in clinical subsets from different countries [Citation9]. To date, there have been a few reports of problems with the Japanese version of AMS [Citation24–26]. Indeed, five of the seven somatic items seemed not to be associated with the somatic factor [Citation26]. The attitudes toward sex in the Japanese culture differ from those of other cultures; we have had concerns about the validity of using the AMS in Japanese subjects. For example, AMS question 12 reads: “Feeling that you have passed the zenith of life”. Unlike questions 15 through 17, one would not expect a Japanese male to interpret question 12 as being related to sexual symptoms. In Japan the phrase “apex or zenith of one’s life” evokes psychological or somatic factors; and most Japanese men will tend to associate this indicator with work, family, and physical potential. Therefore, Japanese subjects would be more likely to interpret question 12 as a request for information about one’s outlook on life as it relates to somatic or psychological symptoms as opposed to a sexual factor. Indeed, in this analysis, this question was categorized as Factor 3 (somatic) together with question 2 “Complaints in joints or muscles” and question 3 “Sweating”. It is difficult to find adequate words in English to describe the images these questions evoke. The most we can say is that question 12 is definitely different from questions 15–17 that ask directly about sexual conditions. When complementarity with AMS is considered, JAMQ might be more useful if it is evaluated by dividing it into three factors. Future studies will have to determine the validity of JAMQ in evaluating the efficacy of therapeutic treatments for LOH.

Question 10 of the JAMQ (i.e. headache) was also misclassified as Factor 1 (psychological) in the factor analysis of this study. We offer the following interpretation of this apparently inconsistent result. About 50% of patients who visit the Men’s Health clinic in Japan have a history of visiting neuropsychiatrists or psychosomatic (i.e. alternative) internal medicine practitioners for depression [Citation11]. Thus, they principally complain of psychological symptoms, such as depression, or vegetative symptoms, such as coldness in one’s hands and feet or sweating. It is common in the Japanese culture for a psychological state to manifest as a somatic symptom. For example, Japanese people tend to “wrap one’s arms over one’s head” when they feel depressed. Hence, it is not unreasonable that symptoms of a headache would be classified as a psychological factor.

Uniquely, questions 13 through 15 in JAMQ ask about lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). (13, Find it hard to urinate or it takes a long time to finish urinating. 14, Frequently feel the urge to urinate during the night. 15, Have difficulty controlling my bladder and sometimes experience incontinence.) AMS does not contain the question about LUTS; however, JAMQ was designed to assess LUTS to enable us to obtain the information regarding LUTS induced via aging. In the current study, we analyzed JAMQ to categorize every question into three specific domains, such as somatic, psychogenic and sexual domain as AMS does. As results, all of these three questions in JAMQ were categorized in the sexual domain. Community-based and clinical data demonstrate a strong and consistent association between LUTS and ED, suggesting that elderly men with LUTS should be evaluated for sexual dysfunction and vice versa [Citation27]. Our study confirmed that questionnaires on LUTS were associated with sexual function by factor analysis. JAMQ is a unique questionnaire that can assess LUTS in LOH patients.

We should address some limitations in this study. First, we examined the correlation between AMS and JAMQ in the heterogeneous population, in which there are male subjects whose testosterone are normal and the symptoms are mild. This study conceives a nature of the pilot study for the clinical application among LOH patients in Japan. Therefore, in this study, total scores of both AMS and JAMQ were not significantly associated with total and free serum testosterone. Thus, neither the AMS nor JAMQ might be suitable tools for screening of LOH. However, recent study shows the testosterone changes in LOH patients are more important and predictive for the LOH symptoms [Citation28]. We need to assess the correlation between the testosterone change and both questionnaires score in the future. Moreover, we should assess the LOH patients with low testosterone level to confirm the exact potential as the screening tool of JAMQ.

This study supports several important conclusions. First, one cannot assume the validity of a questionnaire in other cultures. Factor analysis of the internationally accepted AMS and the JAMQ demonstrated better conformity of the JAMQ to the pre-existing 3-factor model of LOH and less than optimal factorization of the AMS in items pertaining to sexual perceptions in the Japanese population. Whether the differences are semantic or cultural, any questionnaire that has been translated into another language should be subject to rigorous factor analysis before it is applied to the sample. The second and more surprising conclusion is that, cultural differences aside, neither the AMS nor the JAMQ correlated with the signs and symptoms of LOH. This finding seriously limits the relevance of both questionnaires as a screening tool for the identification of LOH, and definitive diagnosis on a clinical basis alone remains out of reach. The JAMQ may still be useful to separately assess the individual aspects of somatic, psychological and sexual symptoms related to LOH in Japanese populations. It remains to be seen whether the JAMQ will be effective for evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of testosterone replacement therapy in the treatment of LOH, and the JAMQ, itself, requires future validation in English.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Reference

- Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in adult men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:1995–2010

- Novak A, Brod M, Elbers J. Andropause and quality of life: findings from patient focus groups and clinical experts. Maturitas 2002;43:231–7

- Horie S. Low testosterone level in men and quality of life. In: Preedy VR, Watson RR, eds. Handbook of disease burdens and quality of life measures. New York: Springer; 2010:2615--31

- Morales A, Lunenfeld B. Investigation, treatment and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males. Official recommendations of ISSAM. International Society for the Study of the Aging Male. Aging Male 2002;5:74–86

- Nieschlag E, Swerdloff R, Behre HM, et al. Investigation, treatment and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males. Aging Male 2005;8:56–8

- Wang C, Nieschlag E, Swerdloff RS, et al. ISA, ISSAM, EAU, EAA and ASA recommendations: investigation, treatment and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males. Aging Male 2009;12:5–12

- Seftel AD. Male hypogonadism. Part I: Epidemiology of hypogonadism. Int J Impot Res 2006;18:115–20

- Heinemann L, Zimmermann T, Vermeulen A, Thiel C. A new “Aging Males Symptoms” (AMS) rating scale. The Aging Male 1999;2:105–14

- Heinemann LA, Saad F, Zimmermann T, et al. The Aging Males’ Symptoms (AMS) scale: update and compilation of international versions. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:15

- Moore C, Huebler D, Zimmermann T, et al. The Aging Males’ Symptoms scale (AMS) as outcome measure for treatment of androgen deficiency. Eur Urol 2004;46:80–7

- Maruyama O, Ide H, Yoshi T, et al. The efficacy of ‘Aging Male Questionnaire’ (Kumamoto) for Japanese PADAM patients. The Aging Male 2006;9:19

- Kratzik C, Heinemann LA, Saad F, et al. Composite screener for androgen deficiency related to the Aging Males’ Symptoms scale. Aging Male 2005;8:157–61

- Hisasue S, Kumamoto Y, Sato Y, et al. Prevalence of female sexual dysfunction symptoms and its relationship to quality of life: a Japanese female cohort study. Urology 2005;65:143–8

- Yokoyama K, Araki S, Matusoka K, et al. Socioeconomic factors affecting alcohol consumption in Japan. Alcoholism 1999;35:13–22

- Takeuchi T, Nakao M, Nishikitani M, Yano E. Stress perception and social indicators for low back, shoulder and joint pains in Japan: national surveys in 1995 and 2001. Tohoku J Exp Med 2004;203:195–204

- Daig I, Heinemann LA, Kim S, et al. The Aging Males’ Symptoms (AMS) scale: review of its methodological characteristics. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:77 . doi:10.1186/1477-7525-1-77

- Nieschlag E, Swerdloff R, Behre HM, et al. Investigation, treatment and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males. ISA, ISSAM, and EAU recommendations. Eur Urol 2005;48:1–4

- Lunenfeld B, Saad F, Hoesl C. ISM, ISSAM, and EAU recommendations for the investigation and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males: scientific background and rationale. The Aging Male 2005;8:59–74

- Duncan A, Hays T. The development of a men’s health center at an integrated academic health center. The J Men’s Health Gender 2005;2:17–20

- Rhoden EL, Morgentaler A. Risks of testosterone-replacement therapy and recommendations for monitoring. N Engl J Med 2004;350:482–92

- Bremner WJ, Vitiello MV, Prinz PN. Loss of circadian rhythmicity in blood testosterone levels with aging in normal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1983;56:1278–81

- Harman SM, Metter EJ, Tobin JD, et al. Longitudinal effects of aging on serum total and free testosterone levels in healthy men. Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001;86:724–31

- Gao HB, Shan LX, Monder C, Hardy MP. Suppression of endogenous corticosterone levels in vivo increases the steroidogenic capacity of purified rat Leydig cells in vitro. Endocrinology 1996;137:1714–8

- Kawa G, Taniguchi H, Kinoshita H, et al. Aging male symptoms and serum testosterone levels in healthy Japanese middle-aged men. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi 2008;99:645–51

- Kobayashi K, Hashimoto K, Kato R, et al. The Aging Males’ Symptoms scale for Japanese men: reliability and applicability of the Japanese version. Int J Impot Res 2008;20:544–8

- Kobayashi K, Kato R, Hashimoto K, et al. Factor analysis of the Japanese version of the Aging Males' Symptoms rating scale. Hinyokika Kiyo 2009;55:475–8

- Gacci M, Eardley I, Giuliano F, et al. Critical analysis of the relationship between sexual dysfunctions and lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol 2011;60:809–25

- Holm AC, Fredrikson MG, Theodorsson E, et al. Change in testosterone concentrations over time is a better predictor than the actual concentrations for symptoms of late onset hypogonadism. Aging Male 2011;14:249–56