Abstract

This study sought to explore the lived experiences of physically active prostate cancer survivors on androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), who exercise individually. Three older men (74–88 years old) with prostate cancer, using ADT continuously for at least 12 months and regularly exercising for at least 6 months, participated in this qualitative pilot study, informed by interpretive phenomenology. Data were gathered using individual semi-structured interviews, audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Coherent stories were drawn from each transcript and analyzed using iterative and interpretive methods. van Manen’s lifeworld existentials provided a framework for interpreting across the research text. Three notions emerged: Getting started, Having a routine and Being with music. Together they reveal what drew the participants to exercising regularly despite the challenges associated with their cancer and treatments. This study provides insights into the benefits of, and what it means for, older men with prostate cancer to regularly exercise individually. These findings may assist cancer clinicians and other allied health professionals to be more attuned to prostate cancer survivors’ lived experiences when undergoing ADT, allowing clinicians to better promote regular exercise to their patients as a foundational component of living well.

Introduction

Prostate cancer has the highest rate of new cancer cases for men in many countries, including New Zealand and Australia [Citation1,Citation2]. As a result of improvements in detection and/or treatments, prostate cancer is now characterized by high 5-year survival rates of 88% [Citation2]. This has resulted in 53 296 Australian men surviving at least 5-years post prostate cancer diagnosis [Citation2].

One of the most common treatments for men with prostate cancer is androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) [Citation3,Citation4], as it is effective for improving overall, disease-free survival [Citation5]. While ADT reduces the progression of the cancer by directly reducing testosterone production, its usage often results in side effects and symptoms that ultimately reduce the men’s overall health, well-being and quality of life [Citation6,Citation7]. These side effects include significant increases in fatigue, alterations in body composition (increased fat mass and reduced muscle and bone mass) as well as reduced physical function and levels of physical activity [Citation8–10]. As most prostate cancer survivors are 65 years of age or older [Citation1], these ADT-related side effects may further contribute to the premature development of other comorbidities including sarcopenia, frailty and osteoporosis [Citation11] as well as cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome [Citation12,Citation13].

With cancer survivorship now becoming increasingly recognized as an integral component of cancer care [Citation14], additional research is now investigating ways to reduce these ADT-related side effects and symptoms. An example of this is the research into the benefits of structured exercise and habitual physical activity. A recent systematic review of this literature indicates that both structured and habitual physical activity have many significant body composition, muscular function, fatigue and quality-of-life benefits for prostate cancer survivors [Citation15]. Unfortunately, only a relatively low proportion of men with prostate cancer are regular exercisers [Citation16–18], even though many of these men believe that exercise is beneficial [Citation19–21].

One reason why many men with prostate cancer may not be physically active is that they perceive more barriers than facilitators to exercise. One of the issues that might impact these barriers and facilitators to physical activity is whether to perform such exercise individually or as a group. This issue has been examined in the breast cancer [Citation22] and wider older adult [Citation23] literatures, with studies comparing the benefits and/or determinants of exercise to these different exercise options. One of the themes that come through these literatures is that it is imperative to have both group- and individual-based exercise options for men with prostate cancer, as there is considerable variation in all population groups regarding the most preferred physical activities and whether such activities are preferentially performed individually or in groups [Citation24,Citation25]. Such inter-individual variation may reflect various factors including each person’s primary barriers, motives and facilitators to physical activity and to the meaning that being physical active plays in their overall lived experience.

Several studies have investigated the determinants of physical activity in men with prostate cancer. Most of these studies have used the theory of planned behavior (a quantitative approach) to gain an insight into the perceived benefits, barriers, motives and facilitators to these men’s physical activity engagement [Citation16,Citation26–28]. Qualitative research methods have also been used to explore men’s prostate cancer experiences, such as older men’s experiences of living with the diagnosis, from newly diagnosed up to five years [Citation29,Citation30], constructions of masculinity [Citation31,Citation32], sex and sexuality [Citation33], undergoing diagnostic imaging procedures [Citation34], having a changed body [Citation35] and andropausal symptoms [Citation36]. While several studies have examined breast cancer survivors’ experiences or patterns of physical activity using a qualitative design [Citation37–40], only three such studies were located examining this issue in men with prostate cancer [Citation19–Citation21]. These two studies observed that the men cited many physical and quality-of-life benefits of being physically active but that they also experienced several barriers to physical activity including fatigue, limited self-efficacy to physical activity engagement, issues accessing community-based group exercise programs and the associated time and monetary costs associated with these group exercise programs [Citation20,Citation21]. Therefore, there is virtually no peer-reviewed literature on how physically active men who exercise alone and are undergoing ADT for prostate cancer describe their exercise experience and how they perceive various barriers and facilitators to such physical activity. The aim of this pilot study was, therefore, to explore the lived experiences of physically active prostate cancer survivors on ADT who have chosen to exercise individually.

Methods

A qualitative descriptive methodology [Citation41], with a hue of interpretive phenomenology [Citation42], guided this exploratory pilot study. The phenomenological hue [Citation41] was deemed appropriate for exploring the “lived-through quality” [Citation42] of the experiences and interpretations of prostate cancer survivors on ADT who chose to exercise alone. Ontologically, it was assumed that the meanings participants ascribed to being an exerciser in the context of being on ADT may be concealed within routine activity patterns or be taken-for-granted. Furthermore, by keeping the questions phenomenological in nature, it was assumed that participants’ stories about exercising may reveal notions beyond just those of the facilitators of, and barriers to, physical activity already reported in the literature. “Being an exerciser” in the context of being on ADT for prostate cancer was the phenomenon of interest. Congruent with the methodology, participants were asked to describe particular exercise moments and events, as well as their understandings of exercising while in recovery. Furthermore, it was assumed that the researcher (WM’s) pre-understandings could not be put to one side or bracketed. In accord, her existing knowledge and prejudices were reflected on prior to data gathering and revisited during data analysis to consider how they may be influencing data interpretation [Citation42,Citation43].

Ethics approval was granted by the Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee 08/58. The study was completed as partial completion of a Bachelor of Health Science Honours degree for WM.

Participants

Inclusion criteria were that the participants had to be older men (65 years or older) living in the community in private residences in Auckland, New Zealand, who had a confirmed diagnosis of prostate cancer, were undergoing ADT for at least 12 months and had been engaged in a regular exercise program for a minimum of six months. Up to five participants were sought; however, locating and recruiting potential participants was more difficult than anticipated.

The study’s three participants were aged between 74 and 88 years old, had been diagnosed with prostate cancer for 3–5 years, were receiving ADT for a period of 3–4 years and had been engaging in regular personal exercise activities for between 2 and 5 years. All three were currently married and living with their spouse.

Procedures

Purposive recruitment method was used. A primary care clinician (urologist) identified nine potentially eligible participants from his patient list. Of these, two were not able to be contacted; the remaining seven were contacted by telephone by WM and sent information packs about the study with a consent form to return via a pre-paid envelope, indicating their voluntary participation for the study. Two men who received information packs were ineligible due to a lack of regular exercise within the previous six months. Of the remaining five men, three gave written consent to participate. No further contact was made with the two potential participants who did not respond.

Data gathering

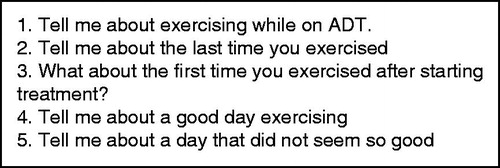

Consistent with the methodology, conversational-style, in-depth individual interviews of 1–1.5 hours using a semi-structured interview schedule were conducted at a time and location of the participants’ choice. All chose to be interviewed at home. With the aim of gathering participants’ in-depth, descriptive accounts of their lived experiences of exercising while undergoing ADT, open questions were used (see ). Probing questions using the participants’ words, where possible, such as say more about feeling too rigid to go to the gym, were used to uncover deeper meanings of the phenomenon of interest. Recruiting one participant at a time, each interview was conducted, audio taped, transcribed verbatim and analyzed by WM prior to conducting an interview with the next participant. In line with the methodology, this process allowed ongoing data analysis to inform the following interview.

Data analysis

Data analysis proceeded by WM reading each participant’s transcript and extracting relevant stories about particular exercising events and the interpretations of what exercising meant to them [Citation42]. Approximately 6–8 discrete stories per participant were identified. Rather than return the entire transcripts to each participant for member checking, these 6–8 stories for each participant were collated and printed, then returned to the specific participant for verification. All participants were happy these transcripts were a true account of their interview and none wanted any aspects of these transcripts to be changed or removed.

An iterative method of data analysis occurred concurrently with subsequent data gathering. Participant’s verified stories and accounts of exercising were read and reread to gain an understanding of each story and the whole text. Each story was then analyzed using van Manen’s [Citation42] selective reading approach by highlighting evocative sections of text and by writing and re-writing interpretations of the meanings within it. Once all participants’ stories were interpreted, an understanding across the whole research text occurred using van Manen’s [Citation42] holistic reading approach. It was a way of moving beyond the individual subjective stories to thematic notions occurring across all participants’ stories. As this method proceeded, notions evident in the text about the exercise context, embodied experiences and embodied time when exercising, and experiencing others, led to using three of van Manen’s [Citation42] four fundamental existentials to guide interpretation of the whole research text: lived space, lived body and lived time. This method allowed shared and unique meanings to emerge which were then grouped under the relevant existential notions.

Trustworthiness in this study was promoted by WM employing research methods consistent with hermeneutic phenomenology and her prior exploration of pre-understandings and reflexive journaling throughout the study. Participants verified the accuracy of their stories and nominated a pseudonym to preserve confidentiality. Engagement in a hermeneutic circle mode of interpreting occurred through moving between the parts, or stories, and the whole of the research text. It was a way of staying grounded in the text while exploring the meanings behind it. The other researchers, VW and JK, guided WM’s engagement in the process and asked questions to promote deep thinking. Criteria used to evaluate this qualitative study’s merit were “aesthetic merit, impact, ontological and educative authenticity, and ethics” [Citation44]. The stories and interpretations were judged as having subjective appeal as they evoked the reader’s emotional and interpretive responses, and they articulated the participants’ lived experiences of particular exercising moments as well as their understanding of these events.

Results

Three notions emerged through analysis within and across the participants’ stories; Getting started, Having a routine and Being with music. While they are articulated separately, in reality they are ontologically interconnected. Each is presented by offering one highly illustrative quote followed by an interpretation of the meanings.

Getting started

Getting started uncovers participants’ experiences of beginning an exercise program. These participants showed determination to be active despite their negative experiences of being diagnosed with, and undergoing treatment for their cancer. Their self-judgments seemed to affect their motivation to participate in exercise as well as their sense of control over the exercise experience.

Joe’s story reflects others’ stories of getting started with exercise:

When I was first diagnosed with prostate cancer, I realised it was serious. I never felt so crook; I asked my Lord to take me. I can’t take anymore; take me. I just wanted to die. I was putting on a tremendous amount of weight. I felt really sick and I did nothing physical, and I felt too rigid to go to the gym. I felt I must keep a positive state of mind so I went to the local gym and signed up.

As Joe describes feeling “so crook”, his words express the profound experience of being faced with the reality of knowing he had prostate cancer and “just wanted to die” He reveals being overwhelmed by the decline in his physical abilities and physicality. Getting his body active meant “keeping positive” and suggests it was his way of getting over feeling like he could not “take any more”. Exercising helped him regain the will to live. As Joe finished this story, he smiled as he explained his daughter was very pleased he had signed up for the same gym she attends. This exercise therefore gave Joe something to focus on in life besides his cancer.

Having a routine

The participants talked about making and having exercise as a routine part of the day. It was about taking the time needed for themselves, being in contact with their own mind and bodies and dwelling in their own world.

Tom’s story stands out as revealing the importance of exercise as part of the day’s routine:

I get up early in the morning and I generally get on [the treadmill] about 10 past 7 and I go until 10 past 8. I just walk. When I first started I thought I don’t think I will last on my own. It was difficult the first time. I felt like doing nothing; I thought I may not make it, I was so weak, I just wanted to die. I think it was my own will power. I wanted to stop but I said that if you stop you will do it all of the time so you have to carry on no matter what. After I completed one hour of my exercise I felt so good and could breathe so much easier; really breathe easier. But you know I never give up, because I thought if you give up you start to make excuses all of the time. So even when I am as sore as everything, I keep on until my hour is up. I just made up my mind you know that I want to get better and it’s all in the mind. I feel so good and feel like I can do anything. Some weekends I will miss it when I go away but when I come back I will go straight back on it. It is good. I do miss it after a while if I go away to Rotorua say for a week to help with family stuff. But then I miss my treadmill, you know, it is my routine. Like a cup of coffee a day you miss it if you don’t have it.

Tom’s story shows how much he looks forward to being on the treadmill each day. And in saying that he does his “hour on the treadmill” even when he is “as sore as everything” Tom discloses his resoluteness to gain control of his health through keeping going with his exercise program. Yet when he reflects back on his first time on the treadmill, we hear how profound his physical weakness was. His words announce his uncertainty; he was not sure he could do it. Yet something within himself made him keep going. Initially, his inner drive was all that kept him going. Yet the regular exercising changed his uncertainty in his physical body to reclaiming his sense of physicality. He “knows” his exercise is good for him. And in saying his exercise is “like a cup of coffee” Tom hints at how compelling being on the treadmill is in his daily routine. In the midst of living with prostate cancer, Tom’s embodied self is drawn to exercise.

Being with Music

While the previous two themes of meaning were common across the three participants, Tom’s next story reveals how music plays a part in his recovery and his exercise regime:

I go into my music room and start playing my sax and singing on the karaoke. It cures me a bit when you are down that’s how I came through it. Yeah, I came through my sickness; it [my music] saved me. You know I love music and when I complete my morning exercise program for an hour, I forget I am working out when listening to music on my ipod. I feel so good and feel like I can do anything.

Being very fond of music, Tom’s words suggest music evokes deep enjoyment and, therefore, is the thing which is most enriching to being in his daily exercise routine. Tom’s experience implies reverence for the mystery of what is happening in the moment, as he states “it cures me a bit”. He suggests the enjoyment, the emotional response, is in itself a healing of the physical body. Being “saved” by music opened up the possibility for Tom to be engaged in his exercise program in a transformative way. The music carried him beyond merely exercising. Listening to music means Tom is in the flow of doing his treadmill workout, while forgetful of being there to exercise. The experience suggests exercise with music opens up a deeper, existential sense of being in the world beyond the context of his prostate cancer.

Discussion

The thematic findings, Getting started, Having a routine and Experiencing music as exercise, describe the subjective experiences of the three prostate cancer survivors participating in exercise within the context of this study. Congruent with hermeneutic phenomenology, three of Van Manen’s [Citation45] four existentials: “lived space”, “lived body”, and “lived time”, informed the method of interpreting across the participants’ stories. The notion of “lived other” was not utilized as it was not deemed relevant to the subjective content of the men’s stories.

Lived space

According to van Manen [Citation45], lived space is felt space. It is the mode in which one’s body inhabits a space and how it affects the way a person feels about themselves [Citation45]. The participants in this study had chosen to exercise individually rather than in a group program setting. Each described experiences of being spiritually attuned to the spaces and places in which they exercised. Recall how Tom spoke of his exercising with music as curing him a bit when he was down. From a phenomenological view, space is not just an external object or an internal experience, but a space sensate awareness that refers us to the world in which we find ourselves [Citation45]. Similarly, seeing life’s possibilities typified men’s attitudes to living, two years after their prostate cancer diagnosis [Citation30]. Livneh [Citation46] identified seeking comfort in, or actively relying on, religion and spirituality as a method used by some cancer patients to increase their psychological well-being and help them live with the medical aspects of their disease. Such spiritual experiences may bring a sense of self-preservation by allowing participants to understand their cancer diagnosis, get on with the treatment and assimilate their diagnosis into their lives [Citation47]. Correspondingly, experiencing enjoyment and gentleness in being physically active were given as reasons for older breast cancer survivors to start and continue exercising post-diagnosis [Citation40].

Although the men in this study did not give a reason for engaging in their own individual exercise programs, their stories suggested a sense of being comfortable doing their own thing in their own way. Such an interpretation is consistent with some older breast cancer survivors who may feel self-conscious in an organized exercise group; particularly, if other group members had different life experiences [Citation40].

Lived body

Interpretively, the notion of the lived body refers to experiencing one’s body as not merely an object in the world but rather a way of being-in-the-world through which one understands and comes to value things. Recall how Joe initially described feeling too rigid to go to the gym. His words were illustrative of how the participants in this study described an embodied sense of exercising initially being too difficult or hard. Such a finding is not surprising based on the wide and varied side effects and symptoms affecting physical function and energy levels that is associated with ADT [Citation9,Citation10]. However, this initial inability to be physically active changed over time as they experienced the benefits of regular exercise, as exemplified by Tom speaking of missing his treadmill when he was away for a few days. Collectively, exercising in the context of living with prostate cancer and being on ADT became something of who these men were, they were exercisers, as well as being a mode of regaining their physical prowess and sense of masculinity. The experience of becoming exercisers rings true with Frank’s [Citation48] interpretation of embodied “craftsmanship” for those who survive cancer. By this Frank [Citation48] refers to the precise way in which people, in the context of survivorship, build and train their bodies; a craft in which “the practical and the creative merge and become indistinguishable”.

Similarly, prostate cancer survivors in other studies spoke of how physical activity provided them with an embodied, confident sense of self [Citation19,Citation20] and how it reduced their anxiety about their cancer treatments and risk of disease progressions [Citation19,Citation21]. And, while not necessarily through physical activity, re-engaging with everyday activities has been interpreted as a way men gain a sense of control over their bodies when living with prostate cancer [Citation30]. Comparable reports about the benefits of physical activity have also been expressed in qualitative studies involving breast cancer survivors. Specifically, the act of performing regular exercise is self-reported as assisting women regain a sense of personal control and strength, improving their body image and physical independence and helping them to embrace life after breast cancer treatment [Citation37,Citation39,Citation40]. The men in this study did not refer to their ADT treatment, although its affects were hinted at in their stories. One interpretation is that they did not want to dwell on its negative effects on their masculinity, but rather focus on the positive role that exercise played in helping them regain their masculine qualities. This interpretation is supported by previous findings that reconstructing masculinity is experienced as important by men post-prostatectomy for prostate cancer [Citation32]. Or the participants may have just wanted to get on with their physical recovery, despite being on ADT; an interpretation congruent with women on hormone therapy not wanting cancer to “interfere with their lives” [Citation40] when getting back into exercise after breast cancer.

Lived time

Lived time or temporality is time as it is lived, not clock time, but subjective time that seems to speed up or slow down depending on what is happening in one’s life [Citation45]. Just as Tom spoke of keeping on until his hour of exercise was up, the participants’ stories revealed events in which time was experienced as going by slowly. Yet, time could also slip away unnoticed such as Tom forgetting he was working out when immersed in exercising. This notion aligns with Breaden’s [Citation49] interpretation of clock time as being less relevant than “self time” for breast cancer survivors. In a similar way, experiencing life as being lived “more fully” in the time one had left was evident for men two years after their prostate cancer diagnosis [Citation30].

Study limitations

Due to the limitations of an Honours degree dissertation for WM, this study drew insights from only a small number of prostate cancer survivors on ADT who regularly exercised. However, qualitative approaches and phenomenology, in particular, are used to uncover deep understandings and therefore a large number of participants is not necessarily needed to achieve this aim [Citation32,Citation50]. Furthermore, this study does not provide the whole picture of the phenomenon of interest. While it provides some insight into the lived experiences of these three men, it does not seek to suggest the meanings will be similar for all prostate cancer survivors engaging in regular exercise. Despite WM being female, participants disclosed deeply personal stories. However, it is not evident whether or how the data obtained may have been different with a male researcher.

Conclusion

The findings of this study may be of assistance to prostate and other cancer survivors by assisting their clinicians better understand the experience of being a prostate cancer survivor on ADT and in particular how individual physical activity may assist in this journey. Turning to the lived experience has made it possible for the essential qualities of the phenomenon in participating in individual physical activity as a prostate cancer survivor on ADT to be described. As many similarities in the stories of these men exist with the literature for physically active breast cancer survivors, such findings may be at least somewhat relevant to other forms of cancer characterized by various physical and psychosocial challenges. Therefore, our findings may be applicable to cancer clinicians, cancer support workers and allied health professionals like nurses, physiotherapists and clinical exercise physiologists who may all have important roles to play in encouraging their cancer patients to use physical activity as a key component of their survivorship process. Future research should involve larger sample sizes and also compare the experiences of these men who exercise in group-based classes to those who exercise alone.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the participants in this study and to the urologist who assisted with recruitment.

References

- Ministry of Health. Cancer: New Registrations and Deaths 2009. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2012

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & Australasian Association of Cancer Registries 2010. Cancer in Australia: an overview, 2010. Cancer series no. 60. Cat. No. Can 56

- Shahinian VB, Kuo Yf, Freeman JL, et al. Increasing use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists for the treatment of localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer 2005;103:1615–24

- Meng MV, Grossfeld GD, Sadetsky N, et al. Contemporary patterns of androgen deprivation therapy use for newly diagnosed prostate cancer. Urology 2002;60:7–11

- Messing EM, Manola J, Yao J, et al. Immediate versus deferred androgen deprivation treatment in patients with node-positive prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. Lancet Oncol 2006;7:472–9

- Gomella LG. Contemporary use of hormonal therapy in prostate cancer: managing complications and addressing quality-of-life issues. BJU Int 2007;99:25–9

- Gooren LJG. Options of androgen treatment in the aging male. Aging Male 1999;2:73–80

- Thorsen L, Courneya K, Stevinson C, Fosså S. A systematic review of physical activity in prostate cancer survivors: outcomes, prevalence, and determinants. Support Care Cancer 2008;16:987–97

- Truong PT, Berthelet E, Lee JC, et al. Prospective evaluation of the prevalence and severity of fatigue in patients with prostate cancer undergoing radical external beam radiotherapy and neoadjuvant hormone therapy. Can J Urol 2006;13:3139–46

- Grossmann M, Zajac JD. Management of side effects of androgen deprivation therapy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2011;40:655–71

- Bylow K, Dale W, Mustian K, et al. Does androgen-deprivation therapy accelerate the development of frailty in older men with prostate cancer? Cancer 2007;110:2604–13

- Kintzel PE, Chase SL, Schultz LM, O'Rourke TJ. Increased risk of metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Pharmacotherapy 2008;28:1511–22

- Newton R, Galvão D. Exercise in prevention and management of cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2008;9:135–46

- Alfano CM, Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Hahn EE. Cancer survivorship and cancer rehabilitation: Revitalizing the link. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:904–6

- Keogh JWL, MacLeod RD. Body composition, physical fitness, functional performance, quality of life, and fatigue benefits of exercise for prostate cancer patients: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;43:96–110

- Keogh JWL, Shepherd D, Krägeloh CU, et al. Predictors of physical activity and quality of life in new zealand prostate cancer survivors undergoing androgen-deprivation therapy. N Z Med J 2010;123:20–9

- Bellizzi KM, Rowland JH, Jeffery DD, McNeel T. Health behaviors of cancer survivors: examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:8884–93

- Coups EJ, Ostroff JS. A population-based estimate of the prevalence of behavioral risk factors among adult cancer survivors and noncancer controls. Prev Med 2005;40:702–11

- Keogh JWL, Patel A, MacLeod RD, Masters J. Perceptions of physically active men with prostate cancer on the role of physical activity in maintaining their quality of life: possible influence of androgen deprivation therapy. Psychooncology 2013. In press

- Craike M, Livingston P, Botti M. An exploratory study of the factors that influence physical activity for prostate cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:1019–28

- Bourke L, Sohanpal R, Nanton V, et al. A qualitative study evaluating experiences of a lifestyle intervention in men with prostate cancer undergoing androgen suppression therapy. Trials 2012;13:208

- Floyd A, Moyer A. Group versus individual exercise interventions for women with breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev 2010;4:22–41

- Cyarto EV, Brown WJ, Marshall AL. Retention, adherence and compliance: important considerations for home- and group-based resistance training programs for older adults. J Sci Med Sport 2006;9:402–12

- Wilcox S, King AC, Brassington GS, Ahn DK. Physical activity preferences of middle-aged and older adults: a community analysis. J Aging Phys Act 1999;7:386–99

- Booth ML, Bauman A, Owen N, Gore CJ. Physical activity preferences, preferred sources of assistance, and perceived barriers to increased activity among physically inactive australians. Prev Med 1997;26:131–7

- Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Rodgers WM, Murnaghan DM. Determinants of exercise intention and behavior in survivors of breast and prostate cancer: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Cancer Nurs 2002;25:88–95

- Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Reid RD, et al. Three independent factors predicted adherence in a randomized controlled trial of resistance exercise training among prostate cancer survivors. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:571–9

- Hunt-Shanks TT, Blanchard CM, Baker F, et al. Exercise use as complementary therapy among breast and prostate cancer survivors receiving active treatment: examination of exercise intention. Integr Cancer Ther 2006;5:109–16

- Krumwiede K, Krumwiede N. The lived experience of men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2012;39:E443–50

- Jonsson A, Aus G, Bertero C. Living with a prostate cancer diagnosis: a qualitative 2-year follow-up. Aging Male 2010;13:25–31

- Rivera-Ramos ZA, Buki LP. I will no longer be a man! Manliness and prostate cancer screenings among Latino men. Psychol Men Masculinity 2011;12:13–25

- Gannon K, Guerro-Blanco M, Patel A, Abel P. Re-constructing masculinity following radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Aging Male 2010;13:258–264

- Walker LM, Robinson JW. Sexual adjustment to androgen deprivation therapy: struggles and strategies. Qual Health Res 2012;22:452–65

- Mathers SA, McKenzie GA, Robertson EM. A necessary evil: the experiences of men with prostate cancer undergoing imaging procedures. Radiography 2011;17:284–91

- Ervik B, Asplund K. Dealing with a troublesome body: a qualitative interview study of men's experiences living with prostate cancer treated with endocrine therapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2012;16:103–8

- Grunfeld EA, Halliday A, Martin P, Drudge-Coates L. Andropause syndrome in men treated for metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Nurs 2012;5:63–9

- Burke SM, Sabiston CM. The meaning of the mountain: exploring breast cancer survivors' lived experiences of subjective well-being during a climb on Mt. Kilimanjaro. Qual Res Sport and Exerc 2010;2:1–16

- Unruh AM, Elvin N. In the eye of the dragon: women's experience of breast cancer and the occupation of dragon boat racing. Can J Occup Ther 2004;71:138–49

- McDonough MH, Sabiston CM, Crocker PRE. An interpretative phenomenological examination of psychosocial changes among breast cancer survivors in their first season of dragon boating. J Appl Sport Psychol 2008;20:425–40

- Whitehead S, Lavelle K. Older breast cancer survivors' views and preferences for physical activity. Qual Health Res 2009;19:894–906

- Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods: whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000;23:334–40

- van Manen M. Researching lived experience: human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. London, Ontario: The Althouse Press; 2001

- Smythe EA, Ironside PM, Sims SL, et al. Doing Heideggerian hermeneutic research: a discussion paper. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45:1389–97

- Sparkes AC, Smith B. Judging the quality of qualitative inquiry: criteriology and relativism in action. Psychol Sport Exerc 2009;10:491–7

- van Manen M. From meaning to method. Qual Health Res 1997;7:345–69

- Livneh H. Psychosocial adaptation to cancer: the role of coping strategies. J Rehabil 2000;44:151–60

- Thomas J, Retsas A. Transacting self-preservation: a grounded theory of the spiritual dimensions of people with terminal cancer. Int J Nurs Stud 1999;36:191–201

- Frank AW. Survivorship as craft and conviction: reflections on research in progress. Qual Health Res 2003;13:247–55

- Breaden K. Cancer and beyond: the question of survivorship. J Adv Nurs 1997;26:978–84

- Carless D, Sparkes AC. The physical activity experiences of men with serious mental illness: three short stories. Psychol Sport Exerc 2008;9:191–210