Abstract

Aim: Variations in diagnosing and treating testosterone (T) deficiency between different regions of the world were analyzed in 2006, and repeated in 2010. At present, the changes since 2006 were analyzed.

Methods: About 731 physicians were interviewed in Europe, South Africa, Central and South America regarding factors determining: (1) prescription of T or withholding T, (2) factors in the long-term use of T and the role of T formulations therein, (3) awareness of the wider spectrum of action of T (cardiometabolic disease) (4) reimbursement of T and its impact on (continued) use and (5) best strategies for information on T for physicians.

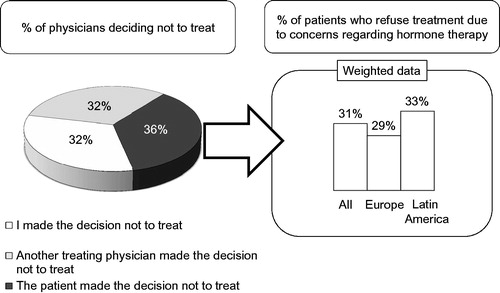

Results: Total T was a key factor in identifying hypogonadism, but for >80% of physicians, clinical symptoms were weighed during diagnosis. Once diagnosed, >85% received T treatment, but the treatment compliance was problematic. Of these patients, 36% decided not to start or continue the treatment.

Conclusion: More hypogonadal men are treated than before, but ∼20% goes unidentified. Physicians have a greater awareness that T deficiency can be an element in cardiovascular and metabolic disease, but more education of physicians on diagnosis and treatment of hypogonadism are needed. Problems with reimbursement of T are barriers in the prescription of T and its use by patients.

Introduction

In an earlier study, carried out in 2006, we analyzed variations between different regions of the world in diagnosing and treating testosterone (T) deficiency [Citation1]. This study addressed the following: (1) reasons/concerns to prescribe or not to prescribe T, (2) what category of T-deficient patients would not receive T on the basis of these concerns, (3) the role of concerns about prostate pathology in the decision not to provide T treatment and (4) further, the role of T in the management of erectile dysfunction (ED) in regard to the advent of efficacious phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors. In a second report where the same issues were broadly addressing, it appeared that at present more men were treated with T. ED and lack of libido (2006) but also depression and obesity [Citation2] were regarded as potential symptoms of T deficiency. To prescribe T for 70% of physicians, severity of complaints was more significant than laboratory values of T. Concerns about prostate disease remained strong and, therefore, 11% of eligible patients did not receive T.

In the present report, the following items were addressed: (1) to explore the evolution of screening, diagnosis and treatment behaviours since 2006, (2) to identify factors that motivate physicians to prescribe T or withhold T treatment from their patients, (3) to determine factors in the long-term use of T treatment and the potential role of the nature of formulation of T preparations, (4) to explore whether the awareness is growing among physicians that T deficiency is associated with a wide spectrum of metabolic and cardiovascular disease, (5) to assess what the impact is of reimbursement of T prescriptions both on prescribing behaviour of physicians and patient acceptance of T treatment and (6) to develop the best strategies, in the view of physicians, to increase insight of physicians into the above items.

Design of the study

The survey was conducted by Blueprint Partnership, Manchester, UK, sponsored by Bayer Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany. Countries were selected on the basis of use of T in the country and local facilities of performing these interviews with physicians who were known to be qualified and the interviews contained ready to answer questions. A 45-min survey was provided by 731 health care professionals across 11 countries (Germany, UK, Spain, Italy, Switzerland, Sweden, Norway, South Africa, Brazil, Mexico and Colombia). This was a larger number of countries than in the earlier surveys reported in 2007 and 2012 in view of the wider use of T since the earlier studies. Of these professionals, 303 were urologists, 115 endocrinologists, 40 cardiologists, 63 internists and 210 primary care physicians. Of these professionals, 469 were from Europe and 262 from Central and South America and South Africa. The study was larger than those in 2010 (292 professionals) and 2006 (353 professionals).

USA was not included in this survey. In contrast to other countries, the direct-to-consumer advertising in USA may trigger substantial patients’ demand for T therapy. This has not only resulted in a higher increase in T prescriptions in USA (see comparison between USA and UK [Citation3]), but also to a heated discussion about safety and indication for T and prescribing habits in USA led by the FDA [Citation4]. In the current situation, it was felt that a survey among US physicians would be strongly influenced and biased by the ongoing debate.

There were a number of criteria for physicians to qualify as respondents in this survey, such as time spent in direct patient care, number of patients with hypogonadism treated in a typical month (at least two patients or one patient in small countries) and the number of patients the physician in question had personally decided to treat with T (>25 = high treatment provider, 5–25 = low treatment provider and non-treating physician if the decision to treat their patients had not been taken by those physicians themselves but by others).

About 40% of patients had received long-term T treatment (>5 years). About 25% had adjustments in the first year of treatment and had therefore been on T treatment for maybe less than one year, the remaining 35% had been on T treatment between 1 and 5 years.

If comparisons are made between the present data and the studies of 2006 and 2010, then it is of note that the analysis of 2015 included different but also more countries than the earlier studies of 2006 and 2010. The use of terminology also varied between the studies with questions in 2006 and 2010 aligned to “patients with T deficiency” and questions in 2015 aligned to “patients with hypogonadism”. Hypogonadism refers to clinical symptoms and proven subnormal T levels upon laboratory measurement.

Statistical significance was assessed using 95% confidence intervals.

Significance testing was run within categories – i.e. between treating and non-treating, between individual markets, between regions and between practice settings. Due to the amount of data, significant market differences were analyzed when they were compared with multiple markets (i.e. one market is significantly higher or lower than the majority of markets in its region), while differences between individual markets are not shown unless considered of particular interest.

Weighting has been applied to patient volume questions only, therefore, proportion estimates provided by physicians with high patient case load contributed more to the data collection than those with a low patient caseload.

Weighting by current caseload is based on the number of adult male hypogonadal patients personally seen in a typical month. Elsewhere weighting has not been applied. The implications of this are in terms of the global total, the balance between the different countries is reflected by the sample size and not by the total population size of that country.

Weighting was applied differently in comparison to the 2010/2006 reports; all data were weighted. General trends were now looked at in comparison to the 2010/2006 reports where applicable, to assess similarities/differences and assess trends in importance, but direct comparison between the findings should be done with caution since all the samples were relatively small. The medical background of physicians who diagnose and treat hypogonadal patients may have varied per region/country. In Scandinavia, the role of primary care physicians is much more significant than in Spain and Italy where specialists are more often the decision-makers. The latter is also the case in Latin America. This may impact on the approach taken to diagnose and treat hypogonadism and associated pathology.

The spectrum of medical conditions associated with hypogonadism

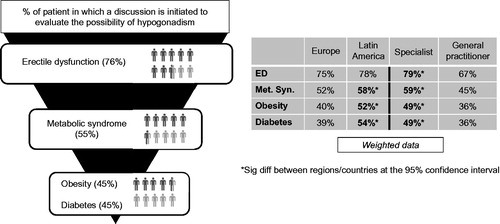

There is an increasing awareness among physicians that T deficiency is associated with a larger array of pathological conditions than sexual dysfunction per se [Citation5]. At present, 94% of physicians recognize this link. The potential association of T deficiency with cardiovascular disease [Citation6] was recognized in 52%, diabetes mellitus in 41%, obesity in 39%, depression in 29%, loss of bone mineral density in 22% [Citation7]. Remarkably, metabolic syndrome only in 11%, though obesity and diabetes mellitus, as features of the metabolic syndrome, were mentioned more frequently. However, when physicians were prompted, this association increased to 48%, behind symptoms such as ED (90%), hyposexual desire (86%), fatigue/low energy (63%), loss of muscle mass/strength (56%) and before symptoms as depression (40%), obesity (37%) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (33%). Obviously, ED features highest to initiate testing for T deficiency (76%), the metabolic syndrome (55%), obesity (45%) and diabetes mellitus (45%) might do the same, more so in Latin America than Europe and more so by specialists than by general practitioners (). Of the patients with erectile problems, 38% turn out to be hypogonadal, 24% of the men with metabolic syndrome, 20% of the obese patients and 18% of the patients with diabetes mellitus.

Testing of T deficiency

Of the physicians interviewed, the following patterns emerged. On a monthly basis, 31 male patients were tested suspecting a low level of T (15% of male patients’ caseload). Of the primary care physicians, 73% will personally order tests for T deficiency and the remaining 27% will refer to a specialist. In Germany, Sweden and South Africa, the specialist is mostly an urologist and in UK, Switzerland and Mexico, patients will be rather referred to an endocrinologist.

Laboratory diagnosis

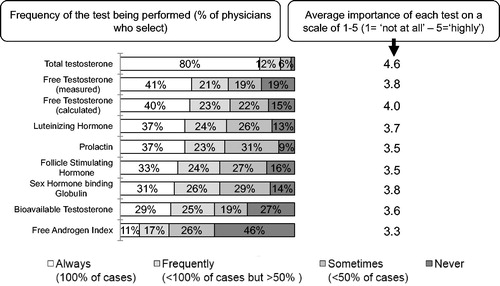

As expected, laboratory measurement of total T figured prominently. In 2015, the scale used was “always” (in 100% of cases), “frequently” (in most cases <100% but >50% of cases), “sometimes” (<50% of cases) and “never”. The data show that total T was measured in the EU in 77% always and 14% frequently, in Latin America, 86% always and 9% frequently. For comparison, in 2006 and 2010, the scale was “never”, “sometimes” and “regularly”. “Regularly” used in 2006 and 2010 should be interpreted as “always”, and is equal to “frequently” in 2015 (). There was no great change from the earlier reports (74% in 2006 report but 76% in 2010 report, possibly due to differences in the weighting applied).

Measurement of free T was reported to be performed frequently by 41% in 2015 (47% in 2010 and 46% in 2006) and sometimes by 40% in 2015 (39% in 2010 and 30% in 2006). Measurement of the main carrier protein of T: sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) was regularly done by 31% in 2015 (by 29% in 2010 and by 32% in 2006) of the respondents and sometimes by 55% (45% in 2010 and 39% in 2006). Free T can be calculated by introducing the value of total T and SHBG into a mathematical model and this was regularly done by 40% in 2015 compared with 37% in 2010 and 29% in 2006 and sometimes by 45% in 2015 as compared with 43% in 2010 and 31% in 2006 of the respondents. The Free Androgen Index (FAI) which is calculated by dividing plasma total T by plasma SHBG (a not very accurate index of free T levels) was used regularly by 11% in 2015 compared with 23% in 2010 and 26% in 2006 regularly and sometimes by 43% in 2015 compared with 53% in 2010 and 28% in 2006. Luteinizing hormone was regularly measured: 37% in 2015 and 32% in 2010 and 62% in 2006, and in 2015, sometimes in 50% compared with 36% in 2010 and 31% in 2006.

Interpretation of the laboratory results

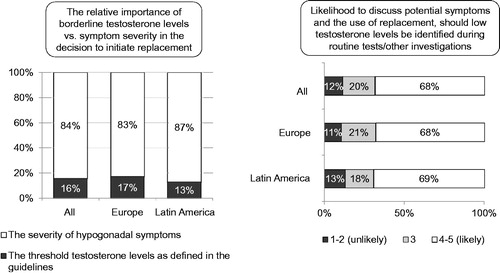

Of the participating physicians, ∼10% did not know the cut off level of T for the diagnosis of hypogonadism. This was particularly true for the physicians who did not initiate T treatment (29%). But 49% used a certain value of total T for the diagnosis of hypogonadism. This was 9.8 nmol/l in Europe and 8.8 nmol/l in Latin America. These values are lower than a cut-off level of 12.0 nmol/l often cited in the literature [Citation8]. Of the respondents, 41% indicated that their diagnosis of hypogonadism did not rest solely on a laboratory value of total T. Of the respondents, 83% in Europe and 87% in Latin America indicated that, in fact, the severity of symptoms of T deficiency carried greater weight to treat with T than the laboratory values (). This was 70% of physicians in 2010 and 72% in 2006. The remaining physicians (13% in Latin America and 17% in Europe) attributed greater importance to the obtained laboratory values, down from 28% in 2006. There was agreement among 87–89% of physicians that subnormal T values detected during routine laboratory tests should, and did in fact, prompt a further enquiry into symptoms of hypogonadism and possible T administration. This was very likely the case with 68–69% of physicians in both Europe and Latin America and likely with 18–21%.

Treatment decisions

Once hypogonadism had been diagnosed 85–87% of the patients received treatment with T. Treatment was initiated in 69–70% by the physicians interviewed. There were no differences between Europe and Latin America. In 2010, men diagnosed with T deficiency who actually received T treatment were divided into men <45 years and men >45 years, Of the men with T deficiency <45 years, 71% received T treatment in 2006 and 74% in 2010. Of the men >45 years, 63% received T treatment in 2006 and 72% in 2010. The reasons why men under 45 years in 2010 did not receive T treatment were that patients did not find it necessary (10%) or opted for alternative treatment (16% in 2010 compared with 7% in 2006) in 2015 of the men who did not receive T treatment, in 32% the attending physician decided not to treat, in 32% another physician had decided not to treat and in 36% the patient was not willing to undergo T treatment ().

Choice of modality of initiating T treatment: modern modalities (long-acting T depot injections and transdermal T) in comparison to other T treatment modalities?

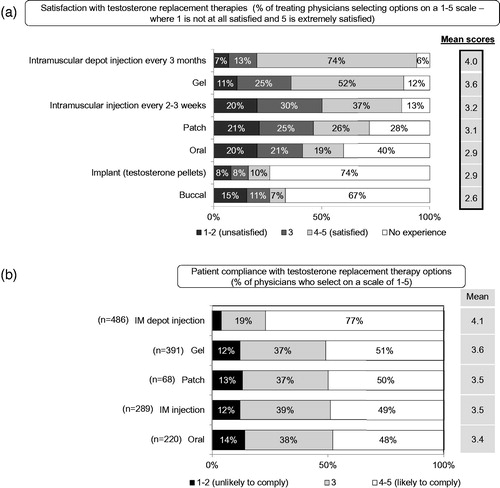

There was no tendency worldwide to start with the more modern T treatment modalities (long-acting depot T or transdermal T); in Europe there was a greater tendency to initiate patients on transdermal T. On a global level, patients starting on long-acting depot T treatment are gaining ground, presently between 18% and 62%. In 2006, 18% were on long-acting T depot [Citation9], in 2010, this was 47% and in 2015 37% with an increase of short-acting T depot injections. It is of note that many more countries were included in the analysis of 2015 (11 countries) compared with five countries in the research of 2010 and 2006. Satisfaction of physicians with treatment modalities of T are depicted in . Treatment satisfaction was highest with T depot injections, followed by T gel. Some treatment modalities such as oral T undecanoate [Citation10] or T by nasal route [Citation11] were not mentioned.

Figure 5. (A) Physicians’ satisfactions with treatment modality of testosterone. (B) Patient compliance with treatment modality of testosterone.

When switching T treatment, treatment with long-acting depot T was the most likely choice (use increased from 43% to 61%). When treatment with long-acting depot T was stopped, transdermal T was the most likely choice.

Compliance

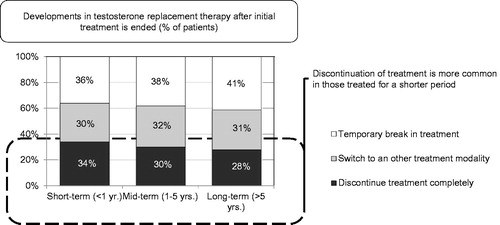

Patient compliance with long-term treatment is a problem of great magnitude, encountered regardless of geographical location or of primary care or specialist practice. Patient compliance is the most commonly selected key driver towards the switching or cessation of treatment in patients (selected by 42–52% of physicians depending on treatment duration). Following this was patient request (selected by 34–37% of physicians), a lack of observable improvement from treatment (selected by 30–35% of physicians) and the financial burden of long-term treatment (selected by 25–28% of physicians). The latter were particularly high in South Africa (selected by 79% of physicians79%). Some kind of problem in this regard was encountered in 49–56% of patients. Stopping treatment was initiated by 36–46% by the patients; this occurred more so if treatment had been relatively short (<12 months) (). Around 31–36% of patients indicated no benefit from T administration or encountered financial problems (26–30%). The latter were particularly high in South Africa (79%). A similar proportion of physicians selected the rise of prostate-specific antigen as a key driver to the switching or cessation of treatment (24–28%), 9–15% selected the enlargement of prostate volume and 9–13% of physicians an increase of haematocrit. Whereas patient compliance, patient request and a lack of observable improvement weigh more for shorter term treatment (<12 months), the latter weighed more in longer term treatment (1–5 years). It was seen that discontinuation of treatment was higher in patients changing treatment approach within 12 months of initiation ().

Figure 6. Development in testosterone replacement therapy after initial treatment is ended (% of patients).

Patient compliance with T treatment modality was highest with T depot injection, followed by T gel, T patch, short-acting T injections and oral T. The compliance with the latter treatment modalities were not really different ().

Financial aspects of treatment with T

Insurance coverage of T treatment varies per country/region of the world. It varies also with T treatment modality. The problem is substantial: only 32% of physicians indicate not to have experienced any reimbursement problem. Particularly, Italy and South Africa feature high in this regard. For oral T, the percentage lies between 6% and 51%; for T gels between 13% and 62%. For short acting, intramuscular T injections were 4–69% and T depot injections were highest between 32% and 89%. There are considerable differences between countries. This being so, it does not gravely impact on the prescription of T itself but may affect choice of T preparations. For instance, short-acting T preparations are more widely used in South Africa than elsewhere.

In some countries, patients will have to pay expenses of (certain types of) T treatment out of their own pocket. In our enquiry, 39% hypogonadal patients currently used a type of T treatment that was widely available and was reimbursed. Among doctors, 17% hesitated to prescribe a type of T treatment that is not reimbursed, and physicians estimated that 41% of hypogonadal patients will not follow the advice to use T treatment if this requires a significant out of pocket payment.

With regard to the more modern T treatment modalities, such as long-acting T depot injections, there would be an 18% reduction in first users and a 14% reduction in patients already receiving this T preparation if there was no reimbursement. For the T gel, these figures would, respectively, be 24% and 13%. There was no clear difference what amount of money patients were prepared to pay out of pocket for new patients and patients already receiving T treatment. It varied per country but the amount was higher in Germany and Switzerland. Of long-acting depot T injection, it was the perception that it was much more expensive than it actually was. For patients who could afford to pay expenses for T treatment out of their own pocket, long-acting depot T was the most widely prescribed T treatment modality.

Education of physicians on T deficiency and treatment

How would physicians like to be educated on T treatment and the potential role of the pharmaceutical industry therein?

Regardless of their geographical locations, physicians received information at medical meetings (63–73%) or equally through journal papers. Internet education and information was mentioned 42–50%. Information via medical representatives was obtained by 31–51%. Training days, marketing material and online training received ratings of 19–35%.

If physicians could express their own wishes in this regard, then medical meetings (95%) or journal papers (95%) were thought most ideal to obtain encourage retention of new information and promote belief, followed by training days (88%) and internet (81%). Visits from sales representatives were valued by 79% and marketing materials by 66%.

Discussion

It is now recognized that hypogonadism is a medical condition that needs to be treated [Citation12]. Hypogonadism not only affects sexual functioning but a wide array of cardiometabolic factors and well-being [Citation13]. There is increasing evidence that hypogonadism contributes to increased morbidity and mortality [Citation12]. It has been debated whether normalization of T level is associated with reduced incidence of myocardial infarction and mortality in men. A recent study points in that direction, showing a reduction in myocardial infarction, stroke and mortality in men treated properly with T, i.e. men achieving physiological T levels under therapy [Citation14].

But still a substantial portion of hypogonadal men remain unidentified. This lack of identification lies mainly with primary care physicians (often gatekeepers of medical treatment) and other non-treaters who express that they would need more guidance with diagnosing and treating hypogonadism in this regard. While complaints such as ED may prompt measurements of T, other conditions associated with hypogonadism (metabolic syndrome, obesity, diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis) [Citation15] do not always present a trigger, particularly with physicians who treat no or few patients with hypogonadism.

Several reports indicate that the use of T medication has risen substantially, both in USA and in Europe [Citation3,Citation4,Citation16,Citation17]. Several authors have expressed concerns that part of these prescriptions has not been justified by the clinical symptoms and particularly by appropriate measurement of serum T in the laboratory [Citation3,Citation4,Citation16–19]. The data collection in these studies was largely retrospective. This survey was not specifically designed to answer the question whether men, before receiving T treatment, had their serum T measured, but it is safe to say, on the basis of the data, that at least 77% of the patients in Europe and 86% in Latin America) had their serum T measured. These figures become 91% and 95%, respectively, if it was assessed whether serum T had been determined in 50–100% of the cases. Though, maybe less than desirable, it compares favourably with the reports of Layton et al. [Citation3] and Nguyen et al. [Citation4].

Initiation of T treatments and compliance with it, particularly in the longer term, need to improve. Beneficial effects of T have a timetable to appear, so not all effects will be manifest in the short term [Citation20]. Physicians should have a better understanding of the benefits of longer term T treatment, particularly with the newer insights of the beneficial effects of T treatment for cardiometabolic health, bone mass and muscle mass, and mood [Citation21,Citation22]. Particularly, the beneficial effects on weight loss and improvement of glucose and lipids are progressive over time for as long as 5–8 years [Citation23–28].

Reimbursement of T treatment presents barriers to the use of T treatment [Citation29]. It is not unreasonable to assume that insurance bodies view T as less vital to a person’s health than is the case with other hormone deficiencies (cortisol, insulin and thyroid hormone). Time has come to update that view. Part of the responsibility should lie with health care professionals in the area of cardiovascular and metabolic disease who themselves lack awareness that T deficiency may be a factor in the diseases they treat (obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, lipid disorders) [Citation30]. A study in Sweden showed that quality-adjusted life-years compared with costs of long-term depot T were cost effective. In addition, if outcomes were expressed as incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-years gained with long-term T depot injection therapy, they compared favourably with no treatment (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio) [Citation31].

With regard to the role of patients, ∼33% of patients decide not to receive treatment. In addition, at some point, ∼33% of patients discontinue after initiation of T treatment, with a temporary intermission at some point in 35–40% of patients. This was somewhat better compared with what had been encountered in the earlier studies of 2006 and 2010 but still a considerable figure, awaiting further analysis since hypogonadism is detrimental to men’s health [Citation12,Citation21].

This study did not include USA, even though USA represents >80% of the world’s T market and where T treatment receives more public attention, also due to the direct-to-consumer advertising. As a result, the discussion about perceived cardiovascular disease risk had more impact in USA than elsewhere [Citation32,Citation33].

Compared with the studies of 2006 and 2010, there were fewer concerns regarding serious side effects of T treatment in the study of 2015. This was justified. Over the last 5 years, several reports have authoritatively indicated that treatment with T has acceptable risks with regard to prostate cancer [Citation34] and cardiovascular risk and that treatment following the existing guidelines is acceptably safe [Citation33,Citation35].

Declaration of interest

The survey was performed by Blueprint Partnership, Manchester, UK, and funded by Bayer Pharma AG, Berlin, Germany. The author has no conflict of interests to declare.

References

- Gooren LJ, Behre HM, Saad F, et al. Diagnosing and treating testosterone deficiency in different parts of the world. Results from global market research. Aging Male 2007;10:173–81

- Gooren LJ,Behre HM. Diagnosing and treating testosterone deficiency in different parts of the world: changes between 2006 and 2010. Aging Male 2012;15:22–7

- Layton JB, Li D, Meier CR, et al. Testosterone lab testing and initiation in the United Kingdom and the United States, 2000 to 2011. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:835–42

- Nguyen CP, Hirsch MS, Moeny D, et al. Testosterone and “age-related hypogonadism” – FDA concerns. N Engl J Med 2015;373:689–91

- Guay AT. Testosterone and erectile physiology. Aging Male 2006;9:201–6

- Yassin A, Saad F, Haider A, Gooren L. The role of the urologist in the prevention and early detection of cardiovascular disease. Arab J Urol 2011;9:57–61

- Yassin A. Testosterone replacement therapy: is there a need for testosterone replacement therapy in older men? Arab J Urol 2010;8:8–10

- Bhasin S, Pencina M, Jasuja GK, et al. Reference ranges for testosterone in men generated using liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry in a community-based sample of healthy nonobese young men in the Framingham Heart Study and applied to three geographically distinct cohorts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:2430–9

- Morales A, Nieschlag E, Schubert M, et al. Clinical experience with the new long-acting injectable testosterone undecanoate. Report on the educational symposium on the occasion of the 5th World Congress on the Aging Male, 9–12 February 2006, Salzburg, Austria. Aging Male 2006;9:221–7

- Jungwirth A, Plas E, Geurts P. Clinical experience with andriol testocaps – the first Austrian surveillance study on the treatment of late-onset hypogonadism. Aging Male 2007;10:183–7

- Mattern C, Hoffmann C, Morley JE, Badiu C. Testosterone supplementation for hypogonadal men by the nasal route. Aging Male 2008;11:171–8

- Muraleedharan V, Jones TH. Testosterone and mortality. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014;81:477–87

- Biswas M, Hampton D, Newcombe RG, Rees DA. Total and free testosterone concentrations are strongly influenced by age and central obesity in men with type 1 and type 2 diabetes but correlate weakly with symptoms of androgen deficiency and diabetes-related quality of life. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2012;76:665–73

- Sharma R, Oni OA, Gupta K, et al. Normalization of testosterone level is associated with reduced incidence of myocardial infarction and mortality in men. Eur Heart J 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv346

- Corona G, Rastrelli G, Maggi M. Diagnosis and treatment of late-onset hypogonadism: systematic review and meta-analysis of TRT outcomes. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;27:557–79

- Baillargeon J, Urban RJ, Kuo YF, et al. Screening and monitoring in men prescribed testosterone therapy in the U.S., 2001–2010. Publ Health Rep 2015;130:143–52

- Jasuja GK, Bhasin S, Reisman JI, et al. Ascertainment of testosterone prescribing practices in the VA. Med Care 2015;53:746–52

- Muram D, Zhang X, Cui Z, Matsumoto AM. Use of hormone testing for the diagnosis and evaluation of male hypogonadism and monitoring of testosterone therapy: application of hormone testing guideline recommendations in clinical practice. J Sex Med 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12968

- Huhtaniemi IT. Editorial Comment on “Use of hormone testing for the diagnosis and evaluation of male hypogonadism and monitoring of testosterone therapy: application of hormone testing guideline recommendations in clinical practice”. J Sex Med 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12972

- Saad F, Aversa A, Isidori AM, et al. Onset of effects of testosterone treatment and time span until maximum effects are achieved. Eur J Endocrinol 2011;165:675–85

- Zarotsky V, Huang MY, Carman W, et al. Systematic literature review of the risk factors, comorbidities, and consequences of hypogonadism in men. Andrology 2014;2:819–34

- Jones TH. Testosterone and cardiovascular disease. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:612–13

- Saad F, Haider A, Doros G, Traish A. Long-term treatment of hypogonadal men with testosterone produces substantial and sustained weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:1975–81

- Yassin A, Doros G. Testosterone therapy in hypogonadal men results in sustained and clinically meaningful weight loss. Clin Obes 2013;3:73–83

- Haider A, Yassin A, Doros G, Saad F. Effects of long-term testosterone therapy on patients with “diabesity”: results of observational studies of pooled analyses in obese hypogonadal men with type 2 diabetes. Int J Endocrinol 2014;2014:683515. doi: 10.1155/2014/683515

- Traish AM, Haider A, Doros G, Saad F. Long-term testosterone therapy in hypogonadal men ameliorates elements of the metabolic syndrome: an observational, long-term registry study. Int J Clin Pract 2014;68:314–29

- Francomano D, Lenzi A, Aversa A. Effects of five-year treatment with testosterone undecanoate on metabolic and hormonal parameters in ageing men with metabolic syndrome. Int J Endocrinol 2014;2014:527470. doi: 10.1155/2014/527470

- Saad F, Yassin A, Doros G, Haider A. Effects of long-term treatment with testosterone on weight and waist size in 411 hypogonadal men with obesity classes I-III: observational data from two registry studies. Int J Obes 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.1139

- Carruthers M, Cathcart P, Feneley MR. Evolution of testosterone treatment over 25 years: symptom responses, endocrine profiles and cardiovascular changes. Aging Male 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.3109/13685538.2015.1048218

- Saad F. The emancipation of testosterone from niche hormone to multi-system player. Asian J Androl 2015;17:58–60

- Arver S, Luong B, Fraschke A, et al. Is testosterone replacement therapy in males with hypogonadism cost-effective? An analysis in Sweden. J Sex Med 2014;11:262–72

- Morgentaler A. Testosterone deficiency and cardiovascular mortality. Asian J Androl 2015;17:26–31

- Morgentaler A, Feibus A, Baum N. Testosterone and cardiovascular disease – the controversy and the facts. Postgrad Med 2015;127:159–65

- Khera M, Crawford D, Morales A, et al. A new era of testosterone and prostate cancer: from physiology to clinical implications. Eur Urol 2014;65:115–23

- Lunenfeld B, Mskhalaya G, Zitzmann M, et al. Recommendations on the diagnosis, treatment and monitoring of hypogonadism in men. Aging Male 2015;18:5–15