Abstract

Background: Patients often have multiple chronic diseases, use multiple prescriptions and over the counter medications resulting in polypharmacy. Many of them store these medications for future use in their homes, rather than take them as directed by their physician, resulting in a waste of health care resources, and potentially dangerous misuse.

Objectives: This study aimed to investigate the magnitude of medication home hoarding, the exchange of medication with family/friends, families’ beliefs about the medication use, source of medication, pharmaceutical class, cost of stored medicine and conditions of storage.

Methods: A structured questionnaire was administered within the homes in two rural areas in Crete.

Results: Forty families participated in the study including 85 individual household members (36 men, and 49 women with an average age of 56.5 ± 24.3 mean ± SD). There were a total of 557 medications recorded, with 324 different medications representing a total value of €8954. The mean quantity of medication boxes stored in each home was 8.5 ± 5.8. Cardiovascular medications accounted for 56% of medications for current use; whereas analgesics (24%), and antibiotics (17%), were the most medications being stored for future use. Exchange of medicine was very common (95%). Beliefs that ‘more expensive medication is more effective’, and that ‘over the counter medications are safe because they were easily available’ were expressed.

Conclusions: Medications are being stored in large quantities in these rural areas, with a large percentage of them being wasted or misused.

KEY MESSAGE(S):

In rural Crete (Greece), people store a large amount of medication at home, often under inappropriate storage conditions

Medication is commonly exchanged between families and friends

Medications, like analgesics and antibiotics, are often stored for future use to treat similar symptoms

Background

Patients with multiple chronic diseases may use multiple medications, both prescription and over the counter (OTC), resulting in polypharmacy, inappropriate use of medications, and increased risk of adverse effects (Citation1–4). Furthermore, many patients stockpile medications in their homes resulting in a waste of health care resources, and potentially dangerous misuse especially of the OTC medication (Citation5–10).

In Greece, a country where many medicines are licensed for sale OTC by pharmacists, little is known about the home storage and use of OTC medicine, though concerns have been raised about the potential dangers of self-medication and abuse of drugs (Citation11–13).

As general practitioners undertaking home visits to patients in rural areas of Crete for many years, we have noticed that patients stored abundant amounts of medicines for current use or for an anticipated illness. Some of these were OTC medications that had been freed from the physicians’ prescriptions to reduce the burden for the primary care services. Concerned by our observations, we aimed to quantify the magnitude of the problem in two rural areas in Crete, and identify beliefs on the medication use. The hypothesis was that a large amount of medications would be stored, that patients would often exchange medications with friends or family, and sometimes uses OTC medication without an appropriate indication. We also hypothesized that some families would hold incorrect beliefs about the medication use (for example: that expensive medication is more effective).

Methods

Setting

A household survey was conducted in two rural areas in the county of Heraklion, in Crete, Greece, in 2008. These mountainous rural areas have approximately 1500 inhabitants with agriculture as their primary employment. The rural areas are served by the first author (I.T.).

Participants

Forty families have finally participated in the study. The families were randomly selected from a register provided by the local authorities that contained precise information about the households. All families approached agreed to participate.

Data collection and instruments

A structured questionnaire with both open and closed questions was administered within the homes of the participating families. The questionnaire was piloted with 10 patients and content and face validity was checked prior to its implementation.

The questionnaire covered the demographics of the household, and details of the number and pharmaceutical class of medications stored, cost of medications, information about their use (current or future) and about who dispensed the medicine. Medicines were classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. Health beliefs and attitudes (for example, about exchanging medications with friends and family, cost related to efficacy) were included in the questionnaire.

The questionnaire also requested information about where medicines were stored to establish whether the storage conditions were appropriate. Inappropriate storage arrangements were defined as positions with high humidity, heat, dust, light and positions easily accessed by the children.

The questionnaire was directed at the person who had the responsibility for the illness management within the family, and who normally determined where medicines were stored, whether or not to use medications, and which to choose.

Ethics

The scientific committee of the Venizeleion Hospital of Heraklion, Crete approved this study. All families willing to participate in the study were informed about the scope and the purpose of the study and gave their written consent.

Analysis of data

The unit of analysis was the family. The calculation of the power of the sample study revealed a need of almost 80 families. As we did not achieve this sample size, the analysis of data was restricted to descriptive statistics. The continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD, while the categorical data was expressed as frequencies and percentages.

Results

Demographic and socio-economical characteristics

Family medication storage and usage was assessed in 40 families. This was half the number of families originally identified as the use of the questionnaire and interview was extremely time consuming and took longer than expected. The 40 families included 85 individuals (36 men and 49 women with an average age of 56.5 ± 24.3 mean ± SD). Demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the interviewees are illustrated in .

Table I. Demographic and socio-economic characteristics of interviewees

Family member responsible for the medication use

In all participating families, the family-member responsible for the illness management, including the selection of the medication and when to use it, was in almost all cases female (). The only exception to this was one household in which a single male lived alone.

Exchange of medications, patients’ beliefs and conditions of medication storage

The study revealed that 38 families (95%) exchanged medications within the family; only two families (5%) did not exchange medications at all. In addition, seven families (17.5%) exchanged medications among friends, relatives, and neighbours. Most medications exchanged were those that were intended for use in the event of future symptoms (e.g. analgesics, antibiotics).

Most samples (60%, 24 out of 40) expressed the belief that the more expensive the medication was, the more effective it would be. In regard to OTC medications, 87.5% (35 out of 40) believed that they were safe because they were so easily available. Inappropriate storage conditions were observed in 80% (n = 32) of the households (usually in the kitchen and the bathroom) and only in 20% (n = 8) were considered appropriate.

Quantity of stored medications

All families had at least one medication in their home. Two families (5%) had one medication stored at home, 17.5% (7 families) had between two and five medications, 27.5% (11 families) had between six and eight medications, and 50% (20 families) had more than eight medications. There were a total of 557 medications reported, representing 324 different medications value. Of the 557 medications, 394 were in current use and 163 were stored for future use. The mean quantity of medications per family being stored for current and future use is reported in .

Table II. Stored medications. Mean values of stored medications per family.

Allocation of stored medications

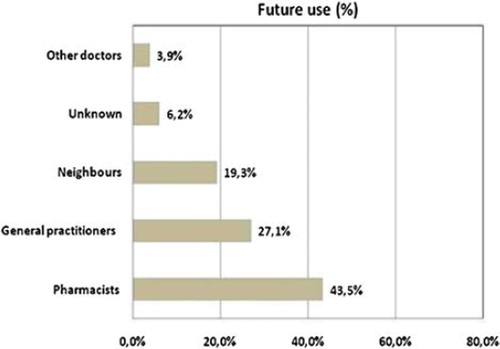

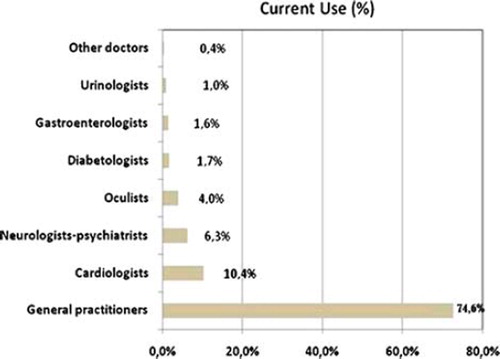

Medications used currently were mainly prescribed by general practitioners and some by specialists. The medications that were stored for future use and used occasionally were mainly purchased from a pharmacist. More details about providers of the stored medications are mentioned in and .

Figure 1. Medication allocation for current use (% of different specialized doctors that prescribed them).

The responses suggested that GPs rarely suggested medications, to be taken only in case of recurrent symptoms (e.g. constipation or low back pain). The only exceptions were paracetamol (8% out of the 24% regarding paracetamol (N02BE01) and constipation medications (laxatives—2% of the total medications stored for future use).

Pharmaceutical classes and cost of stored medications

The most common therapeutic classes of medications according to the ATC system that were stored at home for current use were cardiovascular agents (56%), and for future use analgesics (24%) and antibiotics (17%). More details are given in .

Table III. Type of drugs stored (ATC groups) for current (% of the medicine for current use) and future use (% of the medicine stored for future use).

The mean value of stored medications per family in Euros was 225 ± 320 (mean ± SD). The total value of medications stored for current use was €7414, while for future use it was €1540 and the total value was €8954. On average, families spent 0.6 ± 0.48 % of their monthly income on their medications.

Discussion

Key findings of the study

This pragmatic study conducted in rural areas in the largest island of Greece, revealed how common home storage of medication was. Exchange of medications was common within the family as well as with neighbours, friends and relatives. Some families had incorrect beliefs about the medications use. Many of the medications stored for future use were obtained without a prescription, underlining the important role of pharmacists and general practitioners.

Strengths and limitations

We are aware that this study is predominantly descriptive and its results were based on a small number of families from one geographical location (rural areas of Crete), which limits the generalisation of the study findings (external validity). Although the questionnaire was piloted before its implementation and content and face validity were checked, information about its reliability and internal validity is not available. Time constraints meant that we did not reach our planned sample, which limits the power of the study; though the time spent personally administering the questionnaire enabled an in-depth understanding of medication storage and usage in the families interviewed. Importantly, this study has the benefit of being a pragmatic life study that sampled directly the households in which the medications were stored, not through databases of GPs or pharmacists.

Family member responsible for the medication use

The finding that women were mainly accountable for the medication management has previously been described (Citation9). This underlines the important role of woman in all aspects of health care, including as the main decision maker for the management of the stored medications. The dominant role of women in Crete has been described since the ancient times (Citation14).

Exchange of medications, families’ beliefs, and condition of storage

Exchange of medications (especially analgesics and antibiotics) was common, a finding in accordance with other studies (Citation10,Citation15). One main difference of our study is that we asked about exchange both within and outside the family, whilst other studies restricted their investigation to exchange with neighbours, relatives and friends (Citation5,Citation7,Citation10,Citation11).

In common with Njah et al. (Citation16) we demonstrated that some families have incorrect views about the appropriate use of medications, believing that the more expensive a medication is, the more effective it will be. Similarly, the belief that over the counter medications is safe because they were easily accessible has been reported by Clark et al. (Citation17).

The proper storage conditions are important because they can lead to chemical instability resulting in a reduction in the effectiveness and potential increase in undesirable effects of the medication (Citation18). In the study of Wasserfallen et al. conducted in Switzerland, inappropriate storage conditions were found in 48.8% of the cases (Citation15). Our study revealed higher percentages of inappropriate storage conditions because of our more stringent standards (Citation20).

Medication allocation

The stored medications currently being used for chronic diseases were mainly drugs prescribed by general practitioners or specialists (). The high proportion of drugs given by cardiologists and ophthalmologists probably reflects conditions in which additional testing (such as an echocardiogram, or a split lamp examination) was required at follow up necessitating specialist care.

Most of the medications stored for future use were considered OTC primarily because they were purchased from pharmacists or exchanged from relatives-friends. Even when they were obtained on a past prescription they were considered to be ‘OTC’ because the intention was to use them in the future without medical advice to treat similar symptoms (e.g. the use of antibiotics for symptoms of the common cold). Only the 10% of the medications stored for future use (8% paracetamol and 2% laxatives) were given on the advice of general practitioners to treat medical conditions that require taking drugs in an irregular basis, though there may be some misclassification about the original source of advice on individual drugs.

The medications that were stored for occasional future use were given primarily by a pharmacist. Pharmacists play an important role in the management of OTC medications, which has also been underlined in the literature (Citation19). Abou-Auda reported that the pharmacist was the decision maker in drugs provided in 80.8% of the families studied in Saudi-Arabia (Citation7).

Stored medications

Junius-Walker et al., in a study conducted in Germany reported that 26.7% of interviewees used more than five medications, which is less than half the 67.5% in our study, though the proportion using OTC or prescribed medications are similar (Citation20). The use of OTC medications is a significant problem, which increases the risk of undesirable effects and the drug interactions (Citation21). For example, Barat et al., indentified significant interactions in the 15.3% of the cohort who received OTC medicines (Citation22). A particularly high percentage of OTC medications were reported in our study, in comparison to other studies (Citation10,Citation19,Citation23).

Pharmaceutical classes and cost

In our study cardiovascular drugs accounted for a very high proportion of stored medications, which is also in accordance with other studies (Citation15,Citation20). As described in other studies, analgesics were the most likely drugs stored for future use (Citation7,Citation8,Citation15). It is well recognized that patient's prescribed antibiotics store them for use in future similar illnesses (Citation7–9). This is a particular problem in Greece where people can buy most antibiotics without a prescription, resulting in an increased antimicrobial resistance (Citation12,Citation24).

OTC medications represented a significant percentage of the total cost of medication. Similar results were demonstrated by Wasserfalen et al. (Citation15) and Αbou et al., where the 0.72% of family's total income was used for medications (Citation7).

Implications of the study

Our survey in rural Crete adds to the evidence from a range of healthcare systems on the subject of stored prescribed and OTC medication, which inform European health care strategies. This is particularly pertinent in Greece where the government is targeting the current high cost of pharmaceuticals, so that our findings will be of interest to health policy makers who are struggling to accommodate financial restrictions that will impact on the national health system.

Conclusions

This descriptive study revealed that a large amount of medication is stored in homes, often under inappropriate storage conditions. They are commonly exchanged between families and friends. The most concerning finding was the storage and use of medications without a prescription, based solely on the patient's perceived symptoms. These findings may inform stakeholders and health planners who are currently considering policies to reduce accessibility and cost of pharmaceutical products.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Associate Professor of the Social Medicine Philalithis Anastas, Director of the Master in Public Health and Health Care Management, for his support of this project. The authors should also like to thank Dr Hilary Pinnock for her kind contribution in linguistically checking and editing this manuscript.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Mc Graw C, Drennan V. Self-administration of medicine and older people. Nurs Stand. 2001;15:33–6.

- Goh LY, Vitry AI, Semple SJ, Esterman A, Luszcz MA. Self-medication with over-the-counter drugs and complementary medications in South Australia's elderly population. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2009;9:42.

- Fulton MM, Allen ER. Polypharmacy in elderly: A literature review. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005;17:123–32.

- Bond C, Hannaford P. Issues related to monitoring the safety of over the-counter (OTC) medicines. Drug Saf. 2003;26: 1065–74.

- Kasilo OJ, Nhachi CF, Mutangadura EF. Epidemiology of household medications in urban Gweru and Harare. Cent Afr J Med. 1991;37:167–71.

- Zargarzadeh AH, Tavakoli N, Hassanzadeh A. A survey on the extent of medication storage and wastage in urban Iranian households. Clin Ther. 2005;27:970–8.

- Abou-Auda HS. An economic assessment of the extent of medication use and wastage among families in Saudi Arabia and Arabian Gulf countries. Clin Ther. 2003;25:1276–92.

- Aljinovic-Vucic V, Trkulja V, Lackovic Z. Content of home pharmacies and self-medication practices in households of pharmacy and medical students in Zagreb, Croatia: Findings in 2001 with a reference to 1977. Croat Med J. 2005;46: 74–80.

- Okumura J, Wakai S, Umenei T. Drug utilization and self-medication in rural communities in Vietnam. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:1857–86.

- Yousif MA. In-home drug storage and utilization habits: a Sudanese study. East Mediterr Health J. 2002;8:422–31.

- Antonakis N, Xylouri I, Alexandrakis M, Cavoura C, Lionis C. Seeking prescribing patterns in rural Crete: A pharmacoepidemiological study from a primary care area. Rural Remote Health 2006;6:488.

- Goosens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with ESAC Project Group. Lancet 2005;365:579–87.

- Kontarakis N, Tsiligianni IG, Papadokostakis P, Giannopoulou E, Tsironis L, Moustakis V, . Antibiotic prescriptions in primary health care in a rural population in Crete, Greece. BMC Res Notes 2011;4:38.

- Grammatikakis IE. The woman in Minoic Crete. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2011;24:968–72.

- Wasserfallen JB, Bourgeois R, Bula C, Yersin B, Buclin T. Composition and cost of drugs stored at home by elderly patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:731–7.

- Njah M, Ben Abdelaziz A, Naseur C, Yazid B, Nouira A, Ajmi T. Attitudes and practices in the Sahelian Tunisian population regarding drug usage. Tunis Med. 2002;80:249–54.

- Clark D, Layton D, Shakir SA. Monitoring the safety of over the counter drugs. We need a better way than spontaneous reports. Br Med J. 2001;29:323:706–7.

- Deutsch ME. Keeping drugs at the proper temperature. Science 2004;305:478.

- Sierralta OE, Scott DM. Pharmacists as non prescription drug advisors. Am Pharm. 1995;35:36–8.

- Junius-Walker U, Theile G, Hummers-Pradier E. Prevalence and predictors of polypharmacy among older primary care patients in Germany. Fam Pract. 2007;24:14–9.

- Hersh EV, Pinto A, Moore PA. Adverse drug interactions involving common prescription and over-the-counter analgesic agents. Clin Ther. 2007;29(Suppl.):2477–97.

- Barat I, Andreasen F, Damsgaard EM. The consumption of drugs by 75-year-old individuals living in their own homes. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2000;56:501–9.

- Gonzalez J, Orero A, Prieto J. Storage of antibiotics in Spanish households. Rev Esp Quimroter 2006;19:275–85.

- Eurobarometer study on antimicrobial resistance. April 2010. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_338_sum_en.pdf (accessed 14 October 2010).