Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the validity of a point-of-care test to diagnose infectious mononucleosis (IM) compared with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) specific serology.

Methods: Patients over 14 years with sore throat and four Centor criteria—tonsillar exudate, fever, lymph glands tenderness and absence of cough—and negative pharyngeal testing for group A β-haemolytic streptococcal antigen were consecutively recruited. All patients underwent pharyngotonsillar swab for microbiological culture, the rapid OSOM MonoTest for the diagnosis of IM in whole blood, the Paul–Bunnell test and complete blood analysis with serology for EBV and cytomegalovirus the day after the visit and at 15 days. Sensitivity and specificity were determined.

Results: We included 145 patients with a mean age of 24 ± 6.8 years. Of these, serology was determined in 129 subjects, with IM being diagnosed in 14 (10.9%). Both the MonoTest and the Paul–Bunnell test were positive in 13 patients with IM (92.9%) with no patient without disease being positive for either test—sensitivity of 92.9% (95% CI: 64.2–99.6%) and specificity of 100% (95% CI: 96–100%). The culture showed streptococcus A infection in 1 case (0.7%) and streptococcus C in 62 cases (42.8%). A total of 78 patients presented past infection by EBV (60.5%).

Conclusions: Only one out of 10 patients with sore throat, four Centor criteria and negative rapid test for streptococcal infection presents IM. Despite the MonoTest presenting optimum sensitivity and specificity, it was found to have the same validity as the Paul–Bunnell test, with serological study continuing to be necessary for precise diagnosis of IM.

KEY MESSAGE(S):

In patients with a sore throat, fever, swollen tonsils, tender cervical glands and no cough, almost 40% have a negative throat culture

In patients suspected for infectious mononucleosis, only 10% actually have the disease

Introduction

Infectious mononucleosis (IM) is an acute, self-limiting lymphoproliferative disease caused by the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). The severity of the disease varies, with symptoms that include fever, pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, and malaise (Citation1). Splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, jaundice and splenic rupture can occur but these complications are rare (Citation2). The peak age distribution of IM ranges from 15 to 30 years. Mild infections in younger children may often remain undiagnosed.

A symptom-based diagnosis of IM is not sufficiently accurate, since some clinical symptoms of IM are also detected in other virally induced diseases, such as cytomegalovirus infection, human herpes virus 6, human immunodeficiency virus, adenovirus, herpes simplex virus, as well as in other infections, mainly streptococcal infection or toxoplasmosis. In an acute infection, heterophile antibodies that agglutinate sheep erythrocytes are produced. This process is the basis for the Paul–Bunnell rapid latex agglutination test. This test continues to be popular because of the relative reliability of the antibody as a diagnostic indicator and the ease with which it can be demonstrated, and because the duration of the presence of the antibody usefully reflects the period of clinically significant disease in the sector of the population in which IM is most prevalent (Citation3). None the less, heterophile antibodies may be absent, particularly in young children as well as in many as 20% of adults with EBV IM (Citation4,Citation5). Moreover, it can also be found in patients with diseases other than IM. To perform this test blood must be sent to the laboratory and, in some centres, this is often not carried out until the following morning, with patients frequently not returning to the centre, thereby losing the possibility to diagnose IM. The availability of a point-of-care test in the consulting office would facilitate the diagnosis of this disease. However, studies on the validity of these tests have not shown sufficient sensitivity and specificity for their generalised use in everyday medical practice (Citation6).

Alternatively, antibodies to the viral capsid antigen (VCA), such as VCA-immunoglobulin G (IgG) and/or IgM antibodies (VCA-IgM), are produced slightly earlier than the heterophile antibody and are more specific for EBV infection. The VCA-IgG antibody persists past the stage of acute infection and signals the development of immunity (Citation2,Citation3,Citation7). The main objective of this study was to evaluate the validity of a point-of-care test based on heterophile antibody detection for the diagnosis of primary EBV infection defined by EBV-specific serology. As secondary objectives we determined the demographic, clinical and analytical data of patients with IM compared with those without this disease and established the aetiological causes of patients with suspected IM.

Methods

Study design

We performed a longitudinal, observational study carried out in six consultations in an urban primary care centre from April 2006 to December 2009. Adults aged 14 years or more with acute pharyngitis and the presence of the four Centor criteria (Citation8)—history of fever (temperature > 38.5°C), presence of tonsillar exudates or hypertrophy, presence of tender cervical glands, and absence of cough—and a negative result in a rapid test group A β-haemolytic streptococcus (GABHS) (OSOM Strep. A, Genzyme) were consecutively recruited. The study fulfilled all the regulations referring to observational studies. The Spanish health care authorities were informed and approved the implementation of this study and its characteristics. All the data included in the database were encoded to ensure confidentiality. Consent from patients, parents or legal guardians were obtained prior to participation in the study.

Procedures

All the patients underwent pharyngotonsillar swab for microbiological culture, which was sent to the Department of Microbiology of the Hospital Joan XXIII of Tarragona with AMIES (Copan Innovation, Italy) as medium. Samples were seeded on a plate of blood agar and were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of CO2 at 5% during 48 h. A culture was considered positive for GABHS with a growth of any number of β-haemolytic colonies, Gram staining with streptococcal morphology and a catalase negative test with posterior identification with an automated panel for WIDER Gram positive cocci (Soria Melguizo). Results were confirmed with posterior serogrouping with the Streptococcal Grouping Kit (Oxford, UK). The culture was considered negative after 48 h of incubation with the absence of β-haemolytic colonies.

On determining the presentation of four Centor criteria and a rapid antigen detection test negative for GABHS, informed consent was then requested from the patients to participate in this study. The patients were then referred to a nurse to undergo the rapid OSOM MonoTest (Genzyme) for the diagnosis of IM, with a finger prick to obtain whole blood. This test uses colour immunochromatographic dipstick technology with bovine erythrocyte extract coated on the membrane. Both rapid tests were performed according to manufacturer's instructions.

All patients also underwent the Paul–Bunnell test and complete blood analysis with serology for EBV and cytomegalovirus the day after the visit and at 15 days. EBV specific serologies were used as reference methods. Only specimens with specific IgM to VCA with or without positive VCA-IgG were considered positive. Negative VCA-IgM results with positive VCA-IgG results indicated past infection.

Statistical analysis

Clinical characteristics were compared using the t test for continuous variables and χ2 analysis for categorical variables. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values were calculated from a 2 × 2 table analysis. Statistical significance was accepted at P ≤ 05.

Results

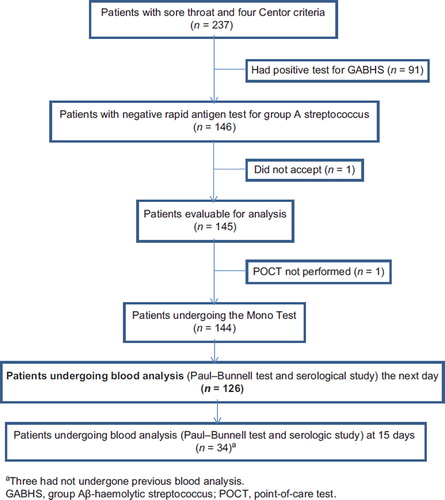

Of the 237 patients with sore throat and four Centor criteria, 146 patients (61.6%) were negative for group A β-haemolytic streptococcus. One patient did not give informed consent to perform the tests and thus the number of patients evaluable was 145 (). Microbiological cultures were performed in all the patients and in all except one the rapid MonoTest was carried out, with 13 being positive (9%) and 131 negative for IM. A total of 126 patients presented the following day for the blood analysis, the Paul–Bunnell test and serology for EBV and cytomegalovirus (86.9%). Only 34 patients returned on day 15 for the second Paul–Bunnell test and serology study (23.4%). Of these, 3 patients did not undergo the blood analysis the first day.

The presence of IM was determined in a total of 129 patients. Of these, the serology of 14 patients (10.9%) was positive for VCA-IgM. describes the demographic, clinical and analytical data of the group of patients with IM compared with the group without active disease. The patients with IM were somewhat younger, presented more fatigue, more nausea and/or vomiting and more palatal petechiae than those without serological evidence of active IM. The leukocyte count, transaminase and gammaglutamyltransferase levels were also significantly greater among the patients with IM. Both the MonoTest and the Paul–Bunnell tests were positive in 13 of the patients serologically diagnosed with active IM (sensitivity of 92.9%; 95% CI: 64.2–99.6%) while none of the patients without disease showed positivity in either the Paul–Bunnell test or the MonoTest (specificity of 100%; 95% CI: 96–100%). The positive and negative predictive values were 100% (95% CI: 71.7–100%) and 99.1% (95% CI: 94.6–99.9%), respectively. The discordant case corresponded to a 16-year-old woman in whom blood analysis was performed twice. In this case, the first Paul–Bunnell test was also negative while the test carried out at 15 days was positive with the serological results for VCA-IgM already being positive the next day. depicts the results of the microbiological study of the pharyngeal swab, indicating that 62 patients were positive for group C β-haemolytic streptococcus (42.8% of all the cultures). It is also of note that only one of the patients with a negative rapid antigen detection test for GABHS had streptococcal pharyngitis by GABHS. A total of 78 patients were VCA-IgM negative and VCA-IgG positive indicating past infection (60.5%). No patient presented acute cytomegalovirus infection while 44 patients were IgG positive for this virus (34.1%).

Table I. Demographic and clinical data depending on the presence or absence of infectious mononucleosis.a

Table II. Results of the throat culture performed.

Discussion

Main results

In primary health care, the clinical diagnosis of IM is confirmed by a heterophile antibody test. Most of the rapid kits commercially available rely on this classic method. In the present study, we compared a point-of-care test (MonoTest) with EBV-specific serology. The MonoTest demonstrated optimum sensitivity greater than 90%, with a specificity of 100%, the same as that of the Paul–Bunnell test.

Limitations

Serology for EBV could not be determined in all the cases since only 126 patients returned the following day for analysis and only 34 came at 15 days, despite a total of 145 patients having accepted to participate in the study. The serological status could not be determined in a total of 14 patients and thus, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution. Another limitation of the study is the definition of disease. To determine whether a patient presents active IM, performance of the EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA-1) together with VCA-IgM and VCA-IgG is recommended, however, this could not be performed in our laboratory. None the less, we do not believe that the results would have significantly differed with this test. We were able to follow all patients with sore throat and four Centor criteria over four years in six consulting offices, recruiting a total of 237 patients. The number of cases observed with IM was; however, lower than expected, with only 14 cases.

Diagnosis challenges

One important aspect to be taken into account is the population analysed. All the results observed in our study specifically refer to those patients with sore throat with four Centor criteria and with a negative result for GABHS, i.e. patients in whom a streptococcal infection is initially highly suspected but the negative result for GABHS makes IM very likely to occur. Among these patients, only 10% of patients with a suspicion of IM actually have this disease. Diagnosis of IM is actually over diagnosed when it is based on clinical grounds. Other mononucleosis-like infections can mimic the symptoms of IM and even though supportive care is the mainstay of the therapy for all these syndromes some other therapies and counselling are specific for IM. Its diagnosis is therefore important in primary care. Furthermore, IM is associated, albeit infrequently, with several severe complications. Owing to the risk of splenic rupture, it has been recommended that athletes avoid returning to sport until four weeks after diagnosis when symptoms have resolved (Citation9). Fatigue resolves more slowly than in other mononucleosis-like infections, since patients usually require about two months to achieve a stable level of recovery (Citation10). For treatment, corticosteroids are recommended in patients with IM and impending airway obstruction caused by tonsillar enlargement.

Prevalence of IM

Few studies have been performed in primary care to determine the prevalence of IM. Aronson et al., (Citation11) studied the prevalence and the clinical and laboratory findings of IM in ambulatory adult patients presenting with sore throat and observed the presence of positive heterophile tests in 2.1% of the patients aged 16 to 73 years. Our result of a little over 10% may be explained by the selection of the subjects since they were required to fulfil four Centor criteria with a negative GABHS result. In the present study, the patients diagnosed with IM more frequently presented fatigue, nausea and vomiting, and palatal petechiae, similar to other reports (Citation11). In addition, the patients with IM presented a high leukocyte count as well as high ALAT and gammaglutamyltransferase levels than patients without IM. Indeed, elevated hepatic transaminase levels are relatively common in patients with IM, occurring in approximately half of the patients (Citation12).

Validity of rapid tests in the diagnosis of IM

summarizes the different studies analysing the validity of rapid tests published so far (13-20). In a Scandinavian study published 10 years ago, the authors analysed different commercial brands and found that the best performing tests in these surveys were Clearview IM (Unipath Limited) and Contrast Mono (Genzyme diagnostics), the latter being very similar to that used in this study (Citation21). Other tests such as those based on polymerase chain reaction have demonstrated greater sensitivity than the heterophile antibody test in children. However, despite being highly specific, they are also very expensive and are, therefore, outside the means of primary care (Citation6).

Table III. Summary of the validity of the rapid tests for the diagnosis of infectious diseases.

In our study the performance of both the Paul– Bunnell and the MonoTest was the same, since they considered the same number of subjects as positive. In addition, one case diagnosed with IM by serology was not detected with either the MonoTest or with classical antibody detection. The advantage of the former is that it costs less (€6.4 one determination versus €8 for a Paul–Bunnell test), avoids blood analyses and perhaps most importantly, avoids the patient leaving the office. Furthermore, this point-of-care test requires minimal training and no specialized laboratory personnel and results are available in five minutes. Another interestingly point is that in our study with patients with a mean age of 24 years, a little more than 60% of the patients had already had EBV infection. This has also been described in other studies and may be explained in that IM in children, particularly under the age of 2 years, may not be clinically expressed.

Importance of other streptococcal infections

Beyond the results of the validity of the test, it is of note that in the present study only 10% of the patients suspected of having IM actually presented the disease. However, infection by group C β-haemolytic streptococcus was much more frequent, and does not require treatment with antibiotics. In addition, if we add all the streptococci observed these infections were five-fold more prevalent among the patients with sore throat fever, cervical adenopathy, exudate, absence of cough and negative GABHS than infection by EBV. In a previous study we observed a greater incidence of 15% of pharyngitis by group C streptococci among patients with two or more Centor criteria (Citation22), but in the present study we only included patients with four Centor criteria and found that less than 40% of these patients presented an aetiology by GABHS and a little over 42% of those who were GABHS negative had Strep C infection.

Conclusion

Clinicians face a diagnostic challenge when a patient with the classic fever, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy triad of infectious mononucleosis has a negative heterophile antibody test. This screening test, although commonly considered sensitive for the presence of EBV infection, may be negative early after infection. With our sample of 129 patients with sore throat, four Centor criteria and a negative rapid test result for GABHS, both the MonoTest and Paul–Bunnell test achieved a sensitivity of 92.9% and a specificity of 100%. The results of this study should be confirmed with other commercial kits including a larger number of cases to achieve more accurate diagnoses in consulting offices. Meanwhile, although the MonoTest could currently replace the Paul–Bunnell test in some cases, serological studies are still required for precise diagnosis. As Terry once asked, if the result of the point-of-care test is negative, can IM be ruled out? (Citation23)

Declaration of interest: To perform this study all the participating primary care physicians were provided with OSOM MonoTest Genzyme strips by the Leti Laboratory. None of the physicians received any direct or indirect economic support from the Leti Laboratory for undertaking this study. Competing interest of CL: He declares having received tests free of charge from Leti for investigational studies. In the last three years Leti has covered the travel and accommodation cots for seeking the inclusion of physicians in a control group in the Happy Audit study in Murcia. Leti also covered the accommodation costs during an international congress on respiratory disease in primary care in 2010.

References

- Hoagland RJ. The clinical manifestations of infectious mononucleosis: A report of two hundred cases. Am J Med Sci. 1960;240:55–63.

- Ebell M. Epstein–Barr virus infectious mononucleosis. Am Fam Physician 2004;70:1279–87.

- Hurt C, Tammaro D. Diagnostic evaluation of mononucleosis-like illness. Am J Med. 2007;120:911.e1–8.

- Sumaya CV, Ench Y. Epstein–Barr infectious mononucleosis in children. II. Heterophile antibody and viral-specific responses. Pediatrics 1985;75:1011–9.

- Gómez MC, Nieto JA, Escribano MA. Evaluation of two slide agglutination tests and a novel immunochromatographic assay for rapid diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:840–1.

- Bell AT, Fortune B, Sheeler R. Clinical inquiries. What test is the best for diagnosing infectious mononucleosis? J Fam Pract. 2006;55:799–802.

- Hess RD. Routine Epstein–Barr virus diagnostics from the laboratory perspective: still challenging after 35 years. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3381–7.

- Centor RM. Witherspoon JM, Dalton HP, Brody CE, Link K. The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room. Med Decis Making 1981;1:239–46.

- Waninger KN, Harcke HT. Determination of safe return to play for athletes recovering from infectious mononucleosis: a review of the literature. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15:410–6.

- Rea TD, Russo JE, Katon W, Ashley RL, Buchwald DS. Prospective study of the natural history of infectious mononucleosis caused by Epstein–Barr virus. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14:234–42.

- Aronson MD, Komaroff AL, Pass TM, Ervin CT, Branch WT. Heterophile antibody in adults with sore throat: frequency and clinical presentation. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96:505–8.

- Grotto I, Mimouni D, Huerta M, Mimouni M, Cohen D, Robin G, . Clinical and laboratory presentation of EBV positive infectious mononucleosis in young adults. Epidemiol Infect. 2003;131:683–9.

- Farhat SE, Finn S, Chua R, Smith B, Simor E, George P, . Rapid detection of infectious mononucleosis-associated heterophile antibodies by a novel immunochromatographic assay and a latex agglutination test. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1597–600.

- Linderholm M, Boman J, Juto P, Linde A. Comparative evaluation of nine kits for rapid diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis and Epstein–Barr virus-specific serology. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:259–61.

- Gerber MA, Shapiro ED, Ryan RW, Bell GL. Evaluations of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay procedure for determining specific Epstein–Barr virus serology and of rapid test kits for diagnosis for infectious mononucleosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:3240–1.

- Elgh F, Linderholm M. Evaluation of 6 commercially available kits using purified heterophile antigen for the rapid diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis compared with EBV specific serology. Clin Diagn Virol. 1996;7:17–21.

- Rogers R, Windust A, Gregory J. Evaluation of a novel dry latex preparation for demonstration of infectious mononucleosis heterophile antibody in comparison with three established tests. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:95–8.

- Gómez MC, Niieto JA, Escribano MA. Evaluation of two slide agglutination tests and a novel immunochromatographic assay for rapid diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:840–1.

- Bruu AL, Hjetland R, Holter E, Mortensen L, Natås O, Petterson W. Evaluation of 12 commercial tests for detection of Epstein–Barr virus-specific and heterophile antibodies. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:451–6.

- De Ory F, Guisasola ME, Sanz JC, García-Bermejo I. Evaluation of four commercial systems for the diagnosis of Epstein–Barr virus primary infections. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:444–8.

- Skurtveit KJ, Bjelkarøy WI, Christensen NG, Thue G, Sandberg S, Hoddevik G. Quality of rapid tests for determination of infectious mononucleosis. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2001;121:1793–7.

- Llor C, Calviño O, Hernández S, Crispi S, Pérez-Bauer M, Fernández Y, . Repetition of the rapid antigen test in initially negative supposed streptococcal pharyngitis is not necessary in adults. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:1340–4.

- Terry LM. Point-of-care testing and recognizing and preventing errors. Br J Nurs. 2002;11:1036–9.