Abstract

Background: Studies investigating interventions, aimed at improving patient satisfaction by exploring the patient's request for help, show conflicting results.

Objectives: To investigate whether writing down the request for help on a request card, prior to the consultation improves patient satisfaction.

Methods: This study was a single-blind randomized controlled trial, in which the patients were blinded to the intervention. Patients were recruited in two rural practices (five GPs) and one urban practice (four GPs) in The Netherlands. Consecutive patients with a new request for help were asked to participate. All patients received general information about patient satisfaction. After randomization, patients in the intervention group were asked to fill in a card with their request(s) for help; the general practitioners started the consultations with these questions. We used the ‘Professional Care’ subscale of the Consultation Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ) to examine the effect of the intervention on patient satisfaction. Secondary outcomes were patient satisfaction measured with the patient's VAS score, the GP's VAS score on satisfaction, consultation time, the other subscales of the CSQ, and the number of consultations during follow-up.

Results: There was no difference in patient satisfaction (CSQ, VAS) between both groups. We also did not find any differences between the other subscales of the CSQ.

Conclusion: A beneficial effect of the use of a ‘request card’ by the patient on patient satisfaction of the consultation could not be demonstrated.

KEY MESSAGE:

Patient satisfaction in primary care is already very high in the Netherlands.

The use of a request card on which the patient can write his request for help, prior to the consultation, has no beneficial effects on patient satisfaction and consultation time.

Introduction

Patient-centred outcomes such as patient satisfaction have become important in evaluating health care nowadays (Citation1). Thoroughly exploring the patient's request for help is considered a requisite for effective communication, which in turn is an important factor in patient satisfaction with the consultation. Request cards, leaflets and pre-visit questionnaires, aimed at encouraging patients to take an active role in the consultation, have generated variable results with respect to patient satisfaction (Citation2–6). One study observed a positive effect on patient satisfaction, but at the cost of an increased consultation time (Citation2). The current study was set up, because of the variable results and concerns regarding the methodological quality of previous studies. The primary objective of this single-blind randomized controlled trial was to evaluate whether a request card filled out by the patient prior to the consultation with the general practitioner (GP), and used by the GP during the consultation, could improve patient satisfaction with the consultation.

Methods

Study design

This study was a single-blinded randomized controlled trial, in which the patients were blinded to the intervention. Patients in both study groups were asked to participate in a patient satisfaction study. Inclusion and randomization was performed by one of the authors in all practices (BSB). Sealed non-transparent envelopes were used for randomization (in blocks of 10). Patients in the intervention group received an envelope with general information about the study and patient satisfaction, and a request card. Patients could fill out one or two questions on this card before consultation. The patients in the control group received an envelope with only general information about patient satisfaction. Patients were instructed to hand over this envelope and, if applicable, the request card to the GP at the beginning of the consultation. The GP used questions on the request card to start the consultation. The study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01466140.

Selection of study subjects

All patients were recruited in two rural practices (5 GPs) and one urban practice (4 GPs) in The Netherlands between January and March 2011. BSB spent five days in the urban practice, and six days in both rural practices for inclusion and randomization. All patients who made an appointment for a new problem were asked to participate, regardless of age. Exclusion criteria were mental disability, no or too little understanding of the Dutch language, illiteracy and limited eyesight.

Measurements

At the end of the consultation, the GP recorded the type of consultation (minor ailment, psychosocial, reassurance or other) and its duration, and his satisfaction with the consultation on a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). Demographic characteristics, medical history, medication use and the number of consultations during one month of follow-up were extracted from the electronic medical records for all patients. Patients were asked for their level of education (low: primary school or less; medium: junior general secondary education, junior secondary pre-vocational education or comparable level of education; high: senior general secondary education, pre- university education or higher). All patients scored their satisfaction (VAS) and filled out the complete ‘Consultation Satisfaction Questionnaire’ (CSQ), which consists of four subscales: ‘general satisfaction,’ ‘depth of relationship,’ ‘perceived time’ and ‘professional care (Citation1).’ The questions of the ‘professional care’ subscale, which we used to examine patient satisfaction with a consultation, cover the following topics: physical examination, giving information about the illness and treatment, agreeing with the advice of the GP and treating patients as an individual. All questions were rescaled to a 100-point scale. For this study, the CSQ was translated into Dutch, according to the World Health Organization criteria (Citation7).

Outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was patient satisfaction measured with the ‘professional care’ subscale of the CSQ (Citation1). Secondary outcomes were patient satisfaction measured with the patient's VAS score, the GP's VAS score on satisfaction, consultation time, the other subscales of the CSQ, and the number of consultations during follow-up.

Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 18.0.3 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois, USA). We used a significance level of 5% for all tests. Categorical variables were compared by using the Chi-Square test. As the scores on the outcome variables were highly skewed to the left the Mann–Whitney test was used to test for the differences between intervention and control group, and the 95% confidence intervals of the differences of the medians are reported. In a previous study, standard deviations of the scores on the subscale ‘Professional Care’ were 11.8 (intervention group) and 16.1 (control group). That study had found a difference of 7.3 points between both groups while the study was originally aimed at detecting a difference of 1.7 points (Citation2). Our sample size calculation was based on a standard deviation of 15. At a power of 90% and an alpha of 5% (two-sided), the sample size required to detect a difference of 7 points on the subscale ‘Professional Care’ was 196 patients. We chose to aim for 210 patients.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Isala Clinics Zwolle, the Netherlands. All patients gave informed consent.

Results

Patient characteristics

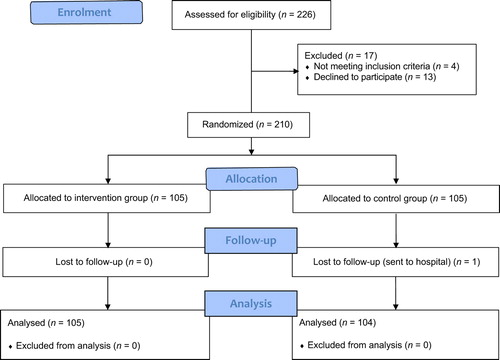

shows the number of participants involved throughout the trial. In the study, 209 patients participated; one patient was lost to follow-up due to a medical emergency. Data on follow-up visits and consultation time were missing for six and 56 patients, respectively. Baseline characteristics of the study group are presented in . In the intervention group, mean age was slightly higher compared to the control group. There was a potential relevant difference between these groups regarding macrovascular complications.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics. The values represent mean ± SD (standard deviation), median (p25–p75) or numbers (%).

Outcomes

shows that the median score of the patients in both groups was 92.9 points on the ‘professional care’ subscale. The 95% confidence interval of the difference between these median scores ranged from 0 to 3.6. The median (interquartile range) VAS satisfaction of patients in both groups was 9.0 (8.0—10.0). There was no difference between groups in the number of consultations for the same problem after one month of follow-up. In addition, no differences were observed on the other subscales of the CSQ.

Table 2. Primary and secondary outcomes.

Discussion

This study showed that patient satisfaction did not improve when patients were asked to write down their request for help. In the past, two studies showed that thoroughly exploring the request for help improved patient satisfaction. In the study by McLean et al., the GP used a written prompt with pre-specified questions (Citation2). Although an increase in patient satisfaction was found, the mean duration of consultation increased with one minute in the intervention group. Little et al., also showed a positive effect on patient satisfaction, but only with short consultations (Citation3). In contrast, three other studies showed no effects on patient satisfaction (Citation4–6). Only one study, using a leaflet as intervention, was a double-blind randomized controlled trial (Citation5). It seems that the described attempts (request cards, leaflets and pre-visit questionnaires) to improve the elicitation of the patient's request for help do not result in greater patient satisfaction.

As this study concerns, there are several possible explanations. First, as in several other studies, patient satisfaction was already high. Therefore, any further improvement was hard to achieve. It is possible that participating GPs already explored the request for help very well. GP's in training in the Netherlands receive extensive communication training (Citation8). Second, it is not unlikely that the GPs were more motivated in thoroughly exploring the request for help in both study groups because they were participating in this study. Finally, the study population consisted of patients with relative high education, which may imply a certain amount of selection on practice level. Perhaps well-educated patients are more capable of expressing their request for help and, therefore, a request card may have less effect on exploring the request for help, and in turn patient satisfaction.

The strength of this study is the sample size and its single-blind study design. It was impossible to blind the doctors to the intervention, because they received the envelopes of the patients. We could have opted for a different control group in which these patients also had to fill in a request card. However, we wanted to compare our intervention with daily practice.

Besides the already mentioned possibility of selection on practice level, this study had some other limitations. At the end of each consultation, we should have asked the patients whether their questions had been answered. Second, the duration of the consultation was missing in 56 participants, which hampers a reliable conclusion. Finally, we included all new requests for help. We have to admit that a request for help is more important when patients are afraid of a certain disease, while with a small problem, the request for help is less important and more obvious.

Conclusion

A beneficial effect of the use of a ‘request card’ by the patient on patient satisfaction, when consulting for mostly minor problems could not be demonstrated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the following general practices and GPs for participating in our study: ‘Westerbeek en Tan-Koning’ (Giethoorn): R. D. Westerbeek, H. Tan-Koning; ‘Kolderveen’ (Nijeveen): P. Speelman, R. Poutsma; ‘De Linden’ (Zwolle): Chr Meyer, C. R. Meeder, H. J. W. Pruijs, A. N. J. Brizar-Zuurmond; ‘Huisartsen Sleeuwijk’ (Sleeuwijk): R. J. P. de Gardeyn, M. F. M. Hoogstraten, S. T. Houweling, M. Biewenga.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper

REFERENCES

- Baker R. Development of a questionnaire to assess patients’ satisfaction with consultations in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40:487–90.

- McLean M, Armstrong D. Eliciting patients’ concerns: A randomized controlled trial of different approaches by the doctor. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:663–6.

- Little P, Dorward M, Warner G, Moore M, Stephens K, Senior J, et al. Randomised controlled trial of effect of leaflets to empower patients in consultations in primary care. Br Med J. 2004;328:441.

- Hornberger J, Thom D, MaCurdy T. Effects of a self-administered previsit questionnaire to enhance awareness of patients’ concerns in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:597–606.

- McCann S, Weinman J. Empowering the patient in the consultation: A pilot study. Patient Educ Couns. 1996;27:227–34.

- Albertson G, Lin CT, Schilling L, Cyran E, Anderson S, Anderson RJ. Impact of a simple intervention to increase primary care provider recognition of patient referral concerns. Am J Managed Care 2002;8:375–81.

- Management of substance abuse. Process of translation and adaption of instruments. http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/ (accessed 16 December 2010).

- Baarveld F, Bottema, BJAM: Raamcurriculum Huisartsopleidingen. Utrecht, SVUH; 2005.