Abstract

Many developed industrialized countries perceive considerable value in developing practice based research networks. In this paper, the development of the Scottish Primary Care Research Network (SPCRN) from 1924–2013 is described. After a false start in the early twentieth century and some local developments 10–15 years ago, the Scottish Primary Care Research Network was finally built upon existing networks of teaching and training practices centred on research active departments of general practice and primary care. This meant that a climate already favourable to research existed and several of the necessary skills were available. Long-term funding commitment to the network by the National Health Service meant that the infrastructure could be developed in the knowledge that it would be likely to become incorporated into wider Scottish and UK systems. Two-thirds of Scottish practices regularly participate in research at a rate of 50–60 studies each year, which result in a range of publications that influence clinical decisions and health policy. As the success of the network grows, greater demands are placed upon it, and the capacity of practices to continue to engage in research may be tested.

KEY MESSAGE:

Scotland's Primary Care Research Network has developed over the last 90 years, after several false starts.

Climate, infrastructure and skills have been identified as the key factors contributing to our development, which may be of interest to other countries or regions.

INTRODUCTION

The overall aim of a Primary Care Research Network (PCRN) is to support and promote high quality research aimed at improving the quality and cost-effectiveness of services offered by the health system as well as securing lasting improvements to health nationally and internationally. In 1924, PCRN initiated by Sir James Mackenzie began to decline and eventually failed (Citation1). Even though the Institute of Clinical Research in St Andrews, Scotland had been directed by ‘the father of general practice based research’ and supported by the UK's Medical Research Council for five years, it could not be sustained as a viable research collaboration once he became too unwell to lead it (Citation2). The rationale for the existence of research in primary care proposed by Mackenzie remains as valid today as it was a century ago (Citation3,Citation4).

The difference between then and now is that several successful research networks exist and several countries, which do not already possess such an organization, are developing them (Citation5). In Scotland, the PCRN has developed through various stages, learning lessons from experience elsewhere, and is now successfully integrated with a range of other primary care academic activities (Citation6).

In the hiatus between 1924 and the successful emergence of a Scottish national network from 1999, there were repeated failures to prosecute primary care research and then successful local and regional network developments. In 1988, an analysis of the difficulties produced a prescient report with three main conclusions (Citation7). For primary care research to succeed there needs to be: a climate of opinion in which research is expected, valued and rewarded; adequate infrastructure such as the resources and advice to support clinicians and the methodological, interpersonal and organizational skills necessary. At that point, the Chief Scientist Office (CSO) in Scotland, which was responsible for health research infrastructure to the National Health Service, did not adopt the recommendations and a further decade had to elapse before the necessary conditions for change developed. Following the Culyer reforms across the UK, in which health service funding to support research was made more explicit, local networks such as WestNet and TayRen were established in 1998 (Citation8,Citation9). In Scotland, the primary care networks were strongly influenced by several years’ experience in the Netherlands as well as evidence emerging from North America and Australia (Citation10–12).

Investigate disease before it leads to pathological changes to facilitate earlier diagnosis.

Investigate the symptoms and signs, which presented in general practice to elucidate their mechanism of production and their significance for the patient.

Study the relationship between environmental factors and disease.

Pay special attention to the investigation and recording of the health and illnesses of children.

One of the principal considerations determining the success of any organization is its ability to match form to function (Citation13). An important report informing developments in Scotland was that provided to the NHS in Southwest England which summarized the options to be considered as shown in (Citation14). The four models vary in the level of complexity and central control, which is reflected in their outputs.

Table 1. Typology of primary care research networks.

OBJECTIVES

In the east of Scotland, the network quickly moved from the mutually supportive, academic, crystal model to the carousel option of TayRen, which more effectively engaged clinicians (Citation15). Under pressure to increase research productivity from funders and universities local networks were amalgamated into larger entities and an orbital model evolved by 2002. This increased efficiency without losing the practitioner engagement, which can be a feature of the more centralized bicycle wheel model. This paper summarizes progress with a PCRN in Scotland where it is embedded in the Scottish School of Primary Care (SSPC), which has two other work streams: programmes of research and academic career development.

METHODS

Network organization

SPCRN is one of six topic-specific networks (diabetes, stroke, medicines for children, mental health and dementia) now funded by the CSO (£377K [€439K] in 2012–13). The network, initially titled Scottish Practices and Professionals engaged in Research (SPPiRe), currently engages with a wide range of primary care health professionals and promotes high quality research in areas for which primary care has particular responsibility. These include disease prevention, health promotion, screening and early diagnosis, as well as the management of long-term conditions, such as arthritis and heart disease. SPCRN is operationally managed at a regional level by the five nodes based in the east, north, northeast, southeast and west of Scotland. The Director and the network manager who provide some national co-ordination are based in the division of Population Health Sciences at the University of Dundee. An efficient mechanism is in place for reimbursing primary care professionals for their involvement in research studies by electronic transfer of funds within four weeks of invoices being received from a budget of £80K [€93K] in 2012–13 (Citation16). A database of professionals interested in PC research in Scotland has gradually grown from 135 to 531 over the past five years, and two-thirds of general medical practices have engaged in at least one project over the past five years (Citation17).

Recruitment to research 2007–13

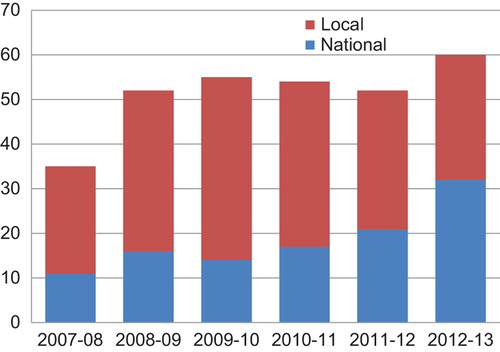

shows the number of national and local studies facilitated by SPCRN 2007–13. The total number of studies, which SPCRN recruited to annually, has increased from 35 in 2007–08 to 60 in 2012–13. The number of national studies has increased from 11 to 32 in this period, and the number of local studies has increased from 24 to 28.

The total number of practices recruited to studies adopted by SPCRN in 2012–13 was 659 compared with 635 in 2007–08. This represents 272 practices, which took part in at least one study adopted by SPCRN in 2012–13, i.e. 27% (272/991) of all general practices in Scotland in 2012 (Citation18).

The study targets for patient recruitment are highly variable as some studies are qualitative and require small numbers and others are clinical trials. The amount of SPCRN resource required per study is not directly related to the number of patients recruited. Where patients with existing conditions are identified from electronic records, the mean number of patients approached for every one recruited to a study is 10. For acute conditions, it is more commonly around one in three (Citation19). The number of patients recruited to SPCRN studies in 2007–08 was 11 952 as a result of several large epidemiological studies such as the Scottish Family Health Study (Generation Scotland) (Citation20). In 2012–13 patient recruitment was 6188 due to a wider range of studies on the SPCRN portfolio including an increased emphasis on clinical trials (Citation21).

Research productivity

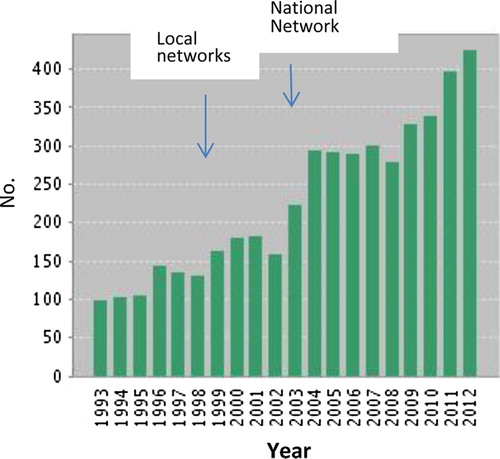

Data from the Web of Science on journal articles published on Primary Care, General Practice or Family Medicine in Scotland show a rise from 160 to over 400 per annum over the period during which the network developed. Although publications of primary care research have increased globally, the rate of increase has been more rapid in countries with established research networks including Scotland (Citation22). The quality of publications also improved significantly with Scottish primary care publications regularly appearing in the highest impact journals (Citation23,Citation24) ().

Public involvement

The process of empowering patients and the public to take an active part in health-related research has been highlighted as an NHS priority. Involvement in research refers to active involvement between people who use services, carers and researchers, rather than the use of people as participants in research as research ‘subjects’ (Citation25). Through patient and public involvement (PPI) in study design and project steering groups, SPCRN encourages research activity to be focused on what will really benefit patients, carers and public using front-line services. The six Scottish topic-specific research networks produced a joint strategy document for PPI in 2009 (Citation26).

Integration of SPCRN with other UK research networks

Scottish primary care researchers have a long tradition of working with colleagues in other parts of the UK and internationally in Europe, Australia, Africa and North America (Citation27,Citation30). The Department of Health (DH) in England has established the Primary Care Research Network (England) (PCRNe), which is part of the UK Clinical Research Network (UKCRN) (Citation31). There are eight Local Research Networks (LRNs) covering the whole of England. Although funding arrangements differ between Scotland and the English regional networks, we try to ensure the conditions for productive collaboration. To ensure that SPCRN is fully collaborating with the PCRN in England, the SSPC Research Manager is a member of the PCRN managers’ group, which meets in London on a monthly basis. In addition, the SSPC Director and the SSPC Research Manager are members of the UK PCRN Advisory Group.

Within Scotland, SPCRN is represented by the SSPC Research Manager at the six-monthly meetings, with CSO and managers of the other Scottish Topic Specific Research Networks and at the NHS R&D Advisory Group meetings. At an operational level, collaboration with the topic-specific research networks is continuing with collaborative work on studies spanning the full spectrum of activity in the networks (Citation32–35).

RESULTS

Improving network efficiency

Many randomized controlled trials fail to recruit enough participants (Citation36). SPCRN has tried to identify the issues which operate in Scotland via pre-trial modelling and to address them using, for example, local electronic record searches and record linkage to some of Scotland's other research assets (Citation37–40). Several studies now use an acute recruitment software tool TrialTorrent, which is similar to developments in other networks such as England's primary care research network (Citation41,Citation42). We have also initiated a ‘direct to patient’ Scottish Health Research Register (SHARE), which will work with practices within the network to enable rapid feasibility studies and patient recruitment (Citation43). This will enable those residents of the country who are willing to allow their health records to be accessed confidentially to identify them as potential study subjects to be approached directly (Citation44).

Enabling factors

SPCRN was built upon an existing network of undergraduate teaching and postgraduate training networks centred on research active departments of general practice and primary care (Citation45,Citation46). This meant that the climate was already favourable and several of the necessary skills were available. A long-term funding commitment to the network by the CSO meant that the infrastructure could be developed in the knowledge that it would be likely to become incorporated into wider Scottish and UK systems. The overall aim of research networks is to support and promote high quality research aimed at improving the quality and cost-effectiveness of services offered by the NHS as well as securing lasting improvements to health nationally and internationally (Citation47,Citation48).

Conclusion

As the success of the network grows, greater demands are placed upon it so the capacity of practices to continue to engage in research may be tested. Unlike England, Scotland does not have a primary care research site initiative incentive scheme, which provides infrastructure funding to primary care practices that agree to support NIHR Clinical Research Network Portfolio studies on a regular basis. Various schemes exist but annual payments range from £1–44K (€1.2–51.3K) (Citation49). As a result, our participation in the RCGP's Research Ready scheme covering the minimum requirements of the Research Governance Framework for undertaking primary care research is limited (Citation50).

The other major limitation is the low capacity of primary care academics that are able to generate study questions which attract external peer-reviewed support. Although the Scottish Clinical Research Excellence Development Scheme enables a small number of aspiring academic general practitioners to undertake academic careers, their numbers are limited to one or two post-doctoral academics each year (Citation51). There is a risk that we may develop excellent research infrastructure in the community and risk seeing it used mainly by hospital colleagues and other scientists who are interested in our patients and whose research is not necessarily relevant to the delivery of primary care.

In the long-term, a PCRN's success depends upon its interaction with clinicians working in primary care and their patients: answering the questions they ask, involving them in study design and conduct; translating research insights into better patient care.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

REFERENCES

- MacNaughton J. The St Andrews Institute for Clinical Research: An early experiment in collaboration. Med. Hist. 2002; 46:549–68.

- Mackenzie J. A defence of the thesis that ‘the opportunities of the general practitioner are essential for the investigation of disease and the progress of medicine.’ Br Med J. 1921;1:797–804.

- Mackenzie J, First Annual Report of the St Andrews Institute for Clinical Research October 1920. Hodder Frowde and Hodder & Stoughton, London.

- Smith BH, Guthrie B, Sullivan FM, Morris AD. A thesis that still warrants defence and promotion. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41: 1518–22.

- Hummers-Pradier E, Bleidorn J, Schmiemann G, Joos S, Becker A, Altiner A, et al. General practice-based clinical trials in Germany—a problem analysis. German ‘clinical trials in German general practice network’. Trials 2012;13:205.

- Ryan K, Wyke S. The evaluation of primary care research networks in Scotland. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:154–55.

- Howie JGR. Report of the working group on research in healthcare in the community. Edinburgh: Chief Scientist Organization, Scottish Home and Health Department; 1988.

- Research and Development Task Force. Supporting research and development in the NHS. London: HMSO; 1994.

- NHS Executive. R&D in primary care: National working group report. London: Department of Health; 1997.

- Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development: English introduction. Available at http://www.zonmw.nl/en/programmes/primary-focus/programme/ (accessed 3 September 2013).

- Starfield B. Is primary care essential? Lancet 1994;344: 1129–33.

- van Weel C, Smith H, Beasley JW. Family practice research networks. Experiences from 3 countries. J Fam Pract. 2000;49: 938–43.

- Hannaford P, Hunt J, Sullivan F, Wyke S. Shaping the future: A primary care research and development strategy for Scotland. Health Bull (Edinb). 1999;57:295–9.

- Exworthy M, Day P, Robinson R, Peckham S, Evans D. Primary care research networks. Project report.: Institute for Health Policy Studies; Southampton, 1997.

- Pitkethly M, Sullivan F. Four years of TayRen, a primary care research and development network. PHCR&D 2003;4:279–83.

- Study flowchart. Available at http://www.sspc.ac.uk/images/SPCRNDocuments/flowchart%20guidance%20for%20researchers%20final3.pdf (accessed 3 September 2013).

- Primary Care Researchers in Scotland (PCRiS). Available at http://chain.ulcc.ac.uk/chain/primarycareresearchers(scotland)_subgroup.html (accessed 3 September 2013).

- http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/General-Practice/Publications/2012-12-18/2012-12-18-GP-Workforce-Report.pdf (accessed 3 September 2013).

- McKinstry B, Hammersley V, Daly F, Sullivan F. Recruitment and retention in a multicentre randomised controlled trial in Bell's palsy: A case study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:15 .

- Smith BH, Campbell H, Blackwood D, Connell J, Connor M, Deary IJ, et al. Generation Scotland: The Scottish family health study; a new resource for researching genes and heritability. BMC Med Genet. 2006;7:74.

- Campbell MK, Snowdon C, Francis D, Elbourne D, McDonald AM, Knight R, et al. Recruitment to randomised trials: Strategies for trial enrolment and participation study. The STEPS study. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11:iii,ix–105.

- Glanville J, Kendrick T, McNally R, Campbell J, Hobbs FD. Research output on primary care in Australia, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States: Bibliometric analysis. Br Med J. 2011;342:d1028.

- Sullivan FM, Swan IRC, Donnan PT, Morrison JMM, Smith BM, McKinstry B, et al. Early treatment with prednisolone or acyclovir and recovery in Bell's Palsy. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1598–607.

- Price D, Musgrave SD, Shepstone L, Hillyer EV, Sims EJ, Gilbert RF, et al. Leukotriene antagonists as first-line or add-on asthma-controller therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1695–707.

- Entwistle VA, O’Donnell M. Research funding organisations and consumer involvement. J Health Serv Res Policy 2003;8 :129–31.

- Patient & public involvement strategy for Scottish topic-specific research networks. Available at http://www.sspc.ac.uk/images/SPCRNDocuments/Scottish%20Topic%20Specific%20Research%20Network%20PPI%20Strategy%202009.pdf (accessed 3 September 2013).

- van Schayck OC, Maas T, Kaper J, Knottnerus AJ, Sheikh A. Is there any role for allergen avoidance in the primary prevention of childhood asthma? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1323–8.

- Mercer SW, Gunn J, Bower P, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Managing patients with mental and physical multimorbidity. Br Med J. 2012;345:e5559.

- Grant L, Brown J, Leng M, Bettega N, Murray SA. Palliative care making a difference in rural Uganda, Kenya and Malawi: Three rapid evaluation field studies. BMC Palliat Care 2011; 10:8.

- Beasley JW, Holden RJ, Sullivan F. Electronic health records: Research into design and implementation. Br J Gen Pract. 2011; 61:604–5.

- Sullivan F, Butler C, Cupples M, Kinmonth AL. Primary care research networks in the United Kingdom. Br Med J. 2007; 334:1093–4.

- Wiles N, Thomas L, Abel A, Ridgway N, Turner N, Campbell J, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for primary care based patients with treatment resistant depression: Results of the CoBalT randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;381:375–84.

- O’Donnell MJ, Xavier D, Liu L, Zhang H, Chin SL, Rao-Melacini P, et al. Risk factors for ischaemic and intracerebral haemorrhagic stroke in 22 countries (the INTERSTROKE study): A case-control study. Lancet 2010; 376:112–23.

- Treweek S, Pearson E, Smith Neville R, Boswell B, Sergeant P, Sullivan F. Desktop software to identify patients eligible for recruitment into a clinical trial: Using SARMA to recruit to the ROAD feasibility trial. Inform Prim Care. 2010;18:51–8.

- Grigg J. Wheeze and intermittent treatment: WAIT parent-determined oral Montelukast therapy for preschool wheeze. Available at http://public.ukcrn.org.uk/Search/StudyDetail.aspx?StudyID = 8869 (accessed 3 September 2013).

- A new pathway for the regulation and governance of health research. Available at http://www.acmedsci.ac.uk/p47prid88.html (accessed 3 September 2013).

- Treweek S, Lockhart P, Pitkethly M, Cook JA, Kjeldstrøm M, Johansen M, et al. Methods to improve recruitment to randomised controlled trials: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Br Med J. Open 2013;3:e002360.

- Treweek S, Ricketts IW, Francis J, Eccles M, Bonetti D, Pitts NB, et al. Developing and evaluating intervention to reduce inappropriate prescribing by general practitioners of antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections: A randomised controlled trial to compare paper-based and web-based modelling experiments. Implement Sci. 2011;6:16.

- Treweek S, Barnett K, Maclennan G, Bonetti D, Eccles MP, Francis JJ, et al. E-mail invitations to general practitioners were as effective as postal invitations and were more efficient. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65 793e797.

- Williams B, Dowell J, Humphris G, Themessl-Huber M, Rushmer R, Ricketts I, et al. Developing a longitudinal database of routinely recorded primary care consultations linked to service use and outcome data. SSM 2010; 70:473–8.

- TrialTorrent. Available at http://www.taydynamic.com/solutions/trialtorrent (accessed 3 September 2013).

- Peterson KA, Delaney BC, Arvanitis TN, Taweel A, Sandberg EA, Speedie S, et al. A model for the electronic support of practice-based research networks. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:560–7.

- Sullivan FM, Treweek S, Grant A, Daly F, Nicolson D, McKinstry B, et al. Improving recruitment to clinical trials with a register of a million patients who agree to the use of their clinical records for research in the Scottish Health Research Register (SHARE). Trials 2011. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-12-S1-A115.

- Scottish Health Research Register. Available at http://www.registerforshare.org/ (accessed 3 September 2013).

- Howie J, Whitfield M. Academic general practice in the UK medical schools, 1948–2000 a short history. Edinburgh University press, Edinburgh, 2011.

- Howie JGR. Patient-centredness and the politics of change: A day in the life of academic general practice. London: Nuffield Trust; 1999.

- Chief Scientist Office Scotland. Available at http://www.cso.scot.nhs.uk/ (accessed 3 September 2013).

- National Institute for Health Research. Available at http://www.nihr.ac.uk/Pages/default.aspx (accessed 3 September 2013).

- Primary Care Research Site initiative. Available at http://www.crncc.nihr.ac.uk/about_us/pcrn/primary_care_practitioners (accessed 3 September 2013).

- RCGP Research Ready. Available at http://www.rcgp.org.uk/clinical-and-research/research-opportunities-and-awards/research-ready-self-accreditation.aspx (accessed 3 September 2013).

- Scottish Clinical Research Excellence Development Scheme. Available at http://www.scotmt.scot.nhs.uk/key-documents/screds.aspx (accessed 3 September 2013).