Abstract

The European General Practice Research Network (EGPRN) and the European Rural and Isolated Practitioner Association (EURIPA) convened a historic joint meeting in Malta in October 2013. Speakers reviewed the inadequacies of the current system and conduct of clinical science research and the use and misuse of the resulting findings. Rural communities offer extraordinary opportunities to conduct more holistic, integrative, and relevant research using new methods and data sources. Investigators presented exciting research findings on questions important to the health of those in rural areas. Participants discussed several strategies to enhance the capacity and stature of rural health research and practice. EGPRN and EURIPA pledged to work together to develop rural research courses, joint research projects, and a European Rural Research Agenda based on the most urgent priorities and the European definition of general practice research in rural health care.

Advances in health care research will come increasingly from rural settings, where resource limits and knowledge of the populations will drive innovation in research methods and questions.

Emerging strategies—such as practice networks linked electronically that generate big data—will make it more feasible to conduct research in rural settings.

INTRODUCTION

Some cling to the myth of the rural family doctor practicing antiquated medicine in tranquil isolation. That myth must give way to the modern reality of cutting edge innovation and complex care systems found in many rural practices. In the future, rural networks linked electronically will produce some of the most creative and important health care research. These were a few of the lessons learned at the October 2013 joint conference in Malta of the European General Practice Research Network (EGPRN) and the European Rural and Isolated Practitioners Association (EURIPA).

This was the first time that the two groups convened a joint meeting. One might wonder what could unite two such unlikely groups. Researchers live in densely populated urban centres and concern themselves with theoretical pursuits. Rural practitioners locate in areas of low population density with limited resources and concentrate on practical solutions to health care problems. The meeting showed both groups that they had much in common. It heralded a new way of thinking about research and rural health care. Participants heard about the significant problems with the current state of medical knowledge. They shared exciting findings on important health care research conducted in rural settings. They came to appreciate the opportunities, and challenges, offered by research initiatives that take advantage of the special micro-cultures found in rural places.

In this paper, we describe the growing concerns over the value of health care research, most of which is conducted in urban academic health centres and involves a small fraction of the population. We argue that rural settings offer great promise for research that will have greater relevance and impact through new methods, subjects, and questions.

RELEVANCE, QUALITY, USE, AND IMPACT OF RESEARCH

Health care research aims to generate evidence that will change practices and improve health outcomes. There are numerous vital factors to consider when assessing the relevance, quality, and impact of the results of research. The investigator(s), subject(s), setting, hypothesis, research methods, and uses of the research findings are some of the more important considerations.

Relevance

A significant portion of the European population is rural, ranging from 32.1% in the south to 20.9% in the north. This compares to 17.8% in North America and 11.3% in Australia and New Zealand (Citation1). Europe also has one of the oldest populations among the world's regions, with a mean age of 41 years compared to 29 years in Asia (Citation2). Europe's old age dependency ratio (number of people older than 64 per 100 people) is 24 and is projected to almost double to 47 by 2050 versus 10 and 27 in Asia, respectively. Studies in England show that the net impact of in-migration of older people and out-migration of younger people was 44.4 for rural areas and 38.5 for urban areas in 2006 (Citation3).

Although more than one in four Europeans (about one in two people worldwide) live in rural areas, most biomedical research takes place in academic health centres based in urban areas. Limited practice specialists generate the vast majority of clinical studies and resulting publications. Primary care doctors provide most care in most health systems. These incongruities raise concerns about relevance when researchers pose narrowly focused questions and recruit primarily urban subjects that may not reflect the needs or nature of the entire population.

There is a gap between the research that is done and the research that needs to be done. That gap will widen as primary care patients and practices become more complex. The rising prevalence and burden of chronic or non-communicable diseases (NCD) demand broader research questions that consider the needs of those with multiple illnesses. Two out of three patients in primary care over age 50 have more than one chronic disease (Citation4). Yet, most studies apply strict criteria to exclude those with diseases other than the condition under study to reduce confounding variables. Excluding patients with multiple chronic diseases from studies may improve the precision, but diminishes the relevance of the findings. Similarly, the relative complexity and complexity per unit time are significantly greater for encounters involving family doctors, than other specialists such as cardiologists or psychiatrists (Citation5). These realities cast doubt on the applicability of research that is focused on narrow questions, excludes subjects with co-morbid conditions, and takes place in urban specialist practices less complex than those of rural primary care.

Quality

Even for urban patients receiving care from specialists, there are serious concerns about the accuracy and durability of clinical intervention trials. Ionnaidis looked at highly cited studies published in major general clinical or high-impact specialty journals over a 14 year period (Citation6). Subsequent studies replicated or confirmed the landmark findings of the highly cited studies only 44% of the time. In effect, this meant that one could better predict the outcome of a coin flip (50%) than whether the findings of a widely cited study in a major journal would prove accurate and enduring (44%). There are several reasons for this disconcerting result. As noted earlier, the setting and subjects of research are important and are not as inclusive as needed. In addition, journals rarely publish research showing negative results or replicating other studies. Finally, the peer review process has been found wanting with major deficiencies in the rigour and quality of manuscript reviews (Citation7).

Use

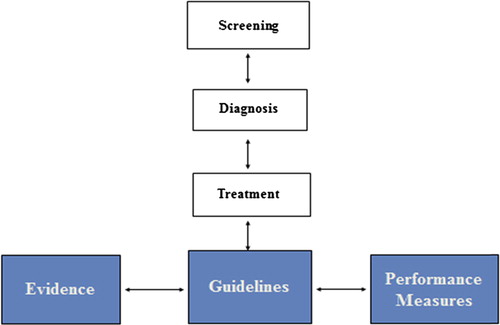

The findings from clinical studies describe the efficacy of the intervention studied. Too often, efficacy is presumed to reflect effectiveness without taking account of the special setting, resources, and highly selected subjects involved in the study. The evidence derived from research is then synthesized into guidelines, recommendations, standards, care pathways, algorithms, or other summarized statements that purport to represent best practice (see ). Guidelines are used increasingly to create performance measures that drive professional behaviour by tracking and rewarding (or punishing) clinicians for adherence to those guidelines.

Different types of guidelines depend on different kinds of evidence and on the order in which they are considered. For instance, implementing screening guidelines is a common task in primary care. Screening guidelines by definition advise looking for a disease in a person who does not yet have symptoms of the disease. Screening guidelines, however, can be developed only after valid treatment and diagnosis guidelines have been developed.

As an example, should a middle-aged man be advised to undergo prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing to screen for prostate cancer? Several types of guidelines and evidence are needed to decide whether PSA testing is useful. First, there must be a treatment guideline based on evidence showing that there are treatments for prostate cancer (surgery, radiation, chemotherapy). Without a treatment to cure or delay the onset of a disease, there is little value in finding the disease. Next, there must be a diagnosis guideline based on evidence that there is an accurate method to diagnose prostate cancer (prostate biopsy). Without an accurate diagnosis of prostate cancer, the treatment will not be applied to appropriate patients (i.e., those diagnosed with prostate cancer). Only after demonstrating valid treatment and diagnosis guidelines can the question be asked whether there is value in screening with PSA testing.

Finally, a screening guideline can be promoted only when there is good evidence that earlier diagnosis and treatment when asymptomatic leads to better outcomes than waiting until symptoms develop. Thus, one must work ‘backwards’ from a treatment guideline to a diagnosis guideline before deciding on a screening guideline. In the case of PSA screening, the controversy has centred on whether there is an effective treatment for prostate cancer that extends or improves quality of life and whether PSA testing is sufficiently discriminatory to identify men at high risk of dying of prostate cancer (Citation8).

Impact

The translation of research findings into the evidence used for guidelines is a laborious task. Study conclusions are usually compiled into an evidence table. To the extent possible, results from all relevant studies are pooled to increase the power of their conclusions. A common error is to assume that a statistically significant result means that the intervention should be recommended. A significant result is only the beginning of the guideline process. The preferences of patients for the benefits, harms, costs, and alternatives to the intervention must then be estimated.

Another frequent mistake when developing guidelines is to extrapolate from studies that provide indirect evidence, such as improvement in an intermediate outcome or indicator, and conclude that the outcomes that matter to patients are also improved (e.g., mortality rate, disability, pain).

An example of this type of mistake involves glycated haemoglobin (haemoglobin A1c, or HbA1c). The conventional wisdom in the diabetes community for many years was that the target for HbA1c should be less than 7.0% for those with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Yet, there were virtually no studies that looked at the impact of such a target on the outcomes experienced by those with diabetes. Several large trials and a meta-analysis recently addressed this issue and found either little or no benefit (Citation9,Citation10) or increased death rates (Citation11) when intensive glucose control efforts kept the HbA1c less than 7.0%. In effect, these large studies suggest that keeping haemoglobin A1c levels below 7.0% would result in 39 000 excess deaths each year for older Europeans with type 2 diabetes (Citation12).

Conflict of interest and the inherent bias that it brings also represent challenges to high quality guidelines. There are potential sources of conflict beyond the obvious one of financial gain received from promoting a certain procedure or product in which one has a vested interest. Many times investigators have built their academic careers and reputations on a particular theory or line of inquiry that may be difficult to discard. It is for these reasons that some have argued for a radical rethinking of how guidelines are developed (Citation13).

RURAL RESEARCH IN THE EUROPEAN CONTEXT

Rural health research is crucial to the provision of quality health care for the rural population of Europe. WHO Europe reported that ‘in the health sector and beyond, limited data and analysis of the situation of rural populations, and in particular of the rural poor, contribute to their invisibility and neglect in policy processes in many countries’ and that ‘the rural dimension is often neglected in analyses of health status and health system performance.’ Data on differences between rural and urban areas on these topics are typically scarce, lacking a comprehensive view of all health system functions, public health governance, and a full spectrum of health issues’ (Citation14). The report concluded that there appeared to be marked rural versus urban health inequalities, especially in Eastern and Southern Europe. Rural populations had a lack of qualified health workers; less access to pharmacies, health promotion and prevention services, and effective emergency care; greater distances to secondary care; and poor general infrastructure (e.g., housing, transport). The lack of data and research are barriers to drawing meaningful conclusions and to informing politicians and health care planners as to needed changes. Failure to adequately study and plan rural health services will lead to a further widening of the rural–urban divide.

Rural life may appear to offer a more peaceful life than the inner city, but landscapes can be deceptive. Sometimes a landscape seems to be less a setting for the life of its inhabitants than a curtain behind which their struggles, achievements and accidents take place (Citation15). ‘Research is the most important tool for identifying those struggles and challenges. Some of the first general practice researchers were rural GPs such as Will Pickles, one of the fathers of modern epidemiology (Citation16).

CREATING BETTER RESEARCH

The first day of the Malta conference provided a glimpse of what better research might look like. There were exciting presentations (Citation17) on the use of electronic technologies to improve care to rural patients in Ireland with multiple chronic diseases and to screen and treat those with alcohol problems in several European countries. A French-based network is providing important information on depression in primary care. Simple reporting and audit systems were described that are helping to improve patient safety in Croatia. After-hours coverage approaches were contrasted between Latvia, Spain, Sweden, and the UK.

The second day focused on the need to build capacity in rural general practice research, develop a standard definition of rural and rural deprivation, work in partnerships with others to generate relevant and useful research, appoint rural physicians to academic positions, establish academic centres of rural health and practice, promote research networks in General Practice, identify priorities for rural practice research, and improve understanding of the complexity and importance of rural issues for health and research.

Conference participants identified a number of urgent research priorities where EGPRN and EURIPA should work together. These included developing and identifying European-specific tools to measure health and poverty in rural populations, assessing the impact of rurality and urbanity on patient care and outcomes, designing rural services to keep care local while assuring best possible outcomes, addressing the impact of ageing rural populations, assessing patient safety in rural settings, understanding the effects of austerity on rural health care systems and outcomes, and exploring the special training needs for rural health care workers so they are fit for purpose.

Participants concluded that Europe lags other parts of the world in supporting rural health care and research, especially Australia, North America, and South Africa. These other regions have established rural medical schools and raised the academic status and capacity of rural practice. A committed, knowledgeable and skilled rural workforce will promote rural practice as a positive career choice, leading to improved recruitment and retention. The unanimous consensus pointed to promoting greater research capacity across Europe as the most urgent priority.

EGPRN and EURIPA committed to working together to improve capacity through rural research courses, joint research projects, and a European Rural Research Agenda based on the most urgent priorities (Citation18) and the European definition of general practice (Citation19).

THE FUTURE IS RURAL RESEARCH

Nearly €300 billion are spent annually on research worldwide. There is a growing consensus that the funds are not well spent. Research must be more relevant and transparent, and better prioritized (Citation20). Against this backdrop of global yearning for more effective research, the Malta conference offered a way forward.

There were several common themes that emerged from the conference and offered a glimpse of why there exist tremendous opportunities for research in the rural setting. Most obvious is that rural health care issues and populations have infrequently been the subject of research. Another reason is that the relative isolation and limited resources in rural communities demand clever and practical strategies. In a way, the historical liabilities of rural health care can become assets in an increasingly connected world where people travel around the world in a day and stay connected continuously through electronic media. Rural communities by contrast tend to be more stable and develop unique micro-cultures that provide shelter from the outside contamination that can skew study results in urban settings.

The rural tradition of collaboration lends itself to the power of practice-based research networks (PBRNs). Through PBRNs, relatively small sample sizes in one small community can be multiplied many times over by collecting data from multiple communities. In the future, there will be new sources of evidence, such as data mining of electronic health record systems, continuous quality improvement projects, and community oriented primary care (COPC) initiatives. Moving from research that reflects a narrow reductionism to a more relevant and comprehensive perspective will require new study designs involving complexity science, qualitative studies, and mixed methods protocols. Promising technologies offer powerful tools for conducting sophisticated research, such as geographic mapping and electronic health records.

The celebrated researchers of tomorrow may well be rural clinicians working as part of a research network with sufficient resources including methodologists, study coordinators, biostatisticians, and other research specialists. One can only imagine the exciting findings that they will present at future conferences—perhaps when they share those findings they will refer back to the common ground they found in Malta.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors should like to thank the rural family doctors who do it all—patient care, teaching, community service, and research. They are our inspiration.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. Both authors received support from EGPRN and EURIPA to attend the conference in Malta.

REFERENCES

- World Urbanization Prospects: The 2011 revision. United Nations: New York, 2012. Available at http://www.unpopulation.org (accessed 5 May 2014).

- Pew Research Center. Attitudes about aging: A global perspective. Chapter 3. Aging in major regions of the world, 2010 to 2050. Available at http://www.pewglobal.org/2014/01/30/chapter-3-aging-in-major-regions-of-the-world-2010-to-2050 (accessed 5 May 2014).

- Commission for rural communities. Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. State of the Countryside Report. Cheltenham: Commission for Rural Communities. 2010. Available at http://www.defra.gov.uk/crc/documents/state-of-the-countryside-report/sotc2010 (accessed 5 May 2014).

- Glynn LG, Valderas JM, Healy P, Burke E, Newell J, Gillespie P, et al. The prevalence of multimorbidity in primary care and its effect on health care utilization and cost. Fam Pract. 2011; 28:516–23.

- Katerndahl DA, Wood R, Jaén CR. A method for estimating relative complexity of ambulatory care. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:341–7.

- Ionnaidis JP. Contradicted and initially stronger effects in highly cited research. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294:218–28.

- Smith R. Peer review: A flawed process at the heart of science and journals. J R S Med. 2006;99:178–82.

- United States Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for prostate cancer. May 2012. Available at http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/prostatecancerscreening.htm (accessed 5 May 2014).

- ADVANCE Collaborative Group. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2560–72.

- Boussageon R, Bejan-Angoulant T, Saadatian-Elahi M, Lafont S, Bergeonneau C, Kassai B, et al. Effect of intensive glucose lowering treatment on all-cause mortality, cardiovascular death, and microvascular events in type 2 diabetes: Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br Med J. 2011;343:d4169.

- The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2545.

- Sinclair AJ, Paolisso G, Castro M, Bourdel-Marchasson I, Gadsby R, Rodriguez Mañas L, et al. European diabetes working party for older people 2011 clinical guidelines for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Executive summary. Diabetes Metab. 2011;37(Suppl. 3):S27–38.

- Lenzer J. Why we can't trust clinical guidelines. Br Med J. 2013;346:f3830.

- Rural poverty and health systems in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2010.

- Berger J. A fortunate man: The story of a country doctor. London: RCGP; 2005.

- Pickles W. Epidemiology in a country practice. London: RCGP; 1984.

- European General Practice Research Network (EGPRN). Abstracts from the first joint EGPRN & EURIPA meeting in Attard, Malta, 17th–20th October, 2013. Theme: Research into different contexts in general practice/family medicine: Rural vs. urban perspectives. Eur J Gen Pract. 2014;20:40–60.

- Lionis C, Stoffers HE, Hummers-Pradier E, Griffiths F, Rotar- Pavlic D, Rethans JJ. Setting priorities and identifying barriers for general practice research in Europe. Results from an EGPRW meeting. Fam Pract. 2004;21:587–93.

- Allen J, Gay B, Crebolder H, Heyrman J, Svab I, Ram P. The European definitions of the key features of the discipline of general practice: The role of the GP and core competencies. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52:526–7.

- Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, Garattini S, Grant J, Metin Gülmezoglu A, et al. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet 2014; 383:156–65.