ABSTRACT

Background Traumatic knee symptoms are frequently seen, however, evidence about the course and prognostic factors are scarce.

Objectives To describe the one and six-year course of traumatic knee symptoms presenting in general practice, and to identify prognostic factors for persistent knee symptoms.

Methods Adolescents (≥12 years) and adults with traumatic knee symptoms (n = 328) from general practice were followed for six years with self-report questionnaires and physical examination.

Results Persistent knee symptoms were reported by 27% of the patients at one year and by 33% at six years. There was a strong relationship (OR: 11.0, 95% CI: 5.0–24.2) between having persistent knee symptoms at one year and at six-year follow-up. Prognostic factors associated with persistent knee symptoms at one year were age, poor general health, history of non-traumatic knee symptoms, absence floating patella and laxity on the anterior drawer test (AUC: 0.72). At six-year follow-up, age, body mass index > 27, non-skeletal co-morbidity, self-reported crepitus of the knee, history of non-traumatic knee symptoms, and laxity on the anterior drawer test were associated with persistent knee symptoms (AUC: 0.82).

Conclusion Traumatic knee symptoms in general practice seem to become a chronic disorder in one out of three patients. Several prognostic factors assessed at baseline were associated with persistent knee symptoms at one and six-year follow-up.

Traumatic knee symptoms in general practice seem to become a chronic disorder in one of three patients.

Having knee symptoms at one-year follow-up is an important predictor of persistent symptoms at six-year follow-up.

Several prognostic factors assessed at baseline are associated with persistent knee symptoms at one and six-year follow-up.

KEY MESSAGES

Introduction

The incidence of traumatic knee symptoms reported in Dutch general practice is about 5.3 per 1000 patients per year.[Citation1] Most of these traumatic knee symptoms arise from sports participation or leisure activities.[Citation2] Therefore, it is assumed that most patients with traumatic knee symptoms in general practice are complaint free in a few weeks and can resume their daily activities.[Citation2]

The few data available on the course of traumatic knee symptoms originate from secondary care.[Citation3] In general practice, all types of knee injuries are seen (mild to severe) ranging from the young athlete to the elderly person with osteoarthritis (OA). In a recent study, we reported that the prognosis of adolescents and young adults with non-traumatic knee symptoms in general practice was not as good as assumed. Persistent knee symptoms were reported by 41% and 19% of the patients at one and six-year follow-up, respectively.[Citation4] In another study, we reported no major differences in the prognosis of knee symptoms between sports participants and non-sports participants in general practice at one-year follow-up. Total recovery was reported by 60% of the sports participants and 51% of the non-sports participants.[Citation5]

Nevertheless, information on the course of patients with traumatic knee symptoms and factors that influence prognosis is also important for general practitioners (GPs) in their management and referral of patients.[Citation6]

Therefore, we assessed in a prospective cohort study in general practice the course of traumatic knee symptoms, and identified prognostic factors for persistent knee symptoms at one and six-year follow-up.

Method

Study setting

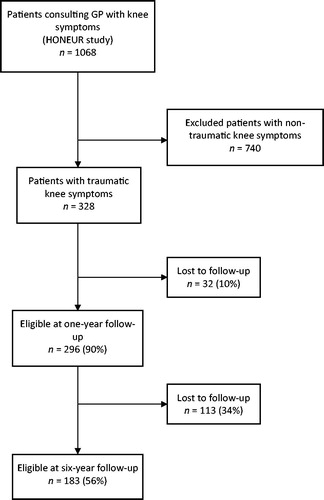

The study took place within the research network HONEUR established by the department of general practice of Erasmus MC. It was part of a prospective, observational cohort study (n = 1068) in which consecutive patients visiting their GP with a new episode of knee symptoms (non-traumatic and traumatic) were enrolled and followed for six years.[Citation7] The study protocol was approved by the medical ethics committee of the Erasmus MC.

Study subjects

At baseline, a new episode of knee symptoms was defined as an episode of symptoms presented to the GP for the first time. Recurrent symptoms for which the GP was not consulted within the past three months were also considered as new episodes. Patients were included in the study from October 2001 to October 2003. Patients were eligible for the present study if they were aged ≥12 years and had consulted their GP for traumatic knee symptoms (). Traumatic knee symptoms were defined as knee symptoms caused by a sudden impact or wrong movement within one year before consulting their GP. Exclusion criteria were knee symptoms that required urgent medical attention (fractures, infection), patients with malignancies, neurologic disorders or musculoskeletal diseases (e.g. Parkinson’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), and patients unable to understand the ramifications of study participation.

Measurements

Patients filled out a self-report questionnaire at baseline, at three, six and nine months follow-up, and at one and six-year follow-up. A standardized physical examination was carried out by a trained physiotherapist at baseline and at one-year follow-up.

At baseline and follow-ups, the questionnaire collected data on age, gender, socioeconomic status, previous knee history of previous injuries or operations, present symptoms, level of daily activities and sports, hindrance and sick leave from daily activities, and health-related quality of life. In addition, the questionnaire at one and six-year follow-up collected data on experienced recovery or worsening of the knee symptoms (outcome). Functional disability and pain were assessed with the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) (assessed at baseline to one-year follow-up), the knee injury osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS) (assessed at six-year follow-up), the medical outcomes study short form 36 health survey (SF-36), the Knee Society Score function questions (KSS), the Lysholm knee scoring scale (all assessed at baseline to six-year follow-up), the Tampa scale for Kinesiophobia (assessed at baseline) and the COOP/Wonca charts (assessed at baseline to one-year follow-up).[Citation8–16] The outcome measurement ‘experienced recovery of knee symptoms’ was measured on a seven-point Likert scale.

Physical examination of the knee consisted of inspection (alignment and joint effusion), palpation (temperature, collateral ligaments, and joint line tenderness), assessment of effusion, passive range of motion in flexion and extension, meniscal tests and knee stability tests.[Citation17,Citation18]

Analysis

Descriptive statistics are used to describe patient/complaint characteristics and experienced recovery. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine which baseline variables from history taking and physical examination were associated with persistent knee symptoms, expressed as odds ratios (OR). The baseline variables used for the univariate analysis were based on literature and clinical relevance; set in a consensus meeting of the authors.[Citation19] The variables were divided into three domains: patient characteristics, complaint characteristics and physical examination findings. To enable easy interpretation of prognostic factors in a clinical setting, we chose to dichotomize most of the variables.

Imputation of missing data was carried out by multiple imputations, creating five imputed datasets.[Citation20–22] Only baseline variables used for logistic regression were imputed.

The variables showing an univariate association with persistent knee symptoms in at least three out of five imputed datasets (P ≤ 0.20), were analysed in a multivariate logistic regression model (backward logistic regression method: entry 0.05, removal 0.10). If a variable was selected in at least three out of five imputed datasets in the multivariate analysis, it was included in the final model (Enter method) and the area under the receiver operating curve (AUC) was calculated. First, separate models for patient characteristics, complaint characteristics, and physical examination findings were built. Subsequently, we combined the remaining variables of each domain to build a model of patient and complaint characteristics, and a model of patient and complaint characteristics together with physical examination findings, to evaluate the addictive value of the different domains. All models were adjusted for gender and age. Separate analyses were performed for the outcome perceived recovery at one and six-year follow-up. Perceived recovery was dichotomized into clinical recovery of knee symptoms (‘completely recovered’ and ‘much improved’) versus persistent knee symptoms (‘slightly improved,’ ‘no change,’ ‘slightly worsened,’ ‘much worsened’ and ‘worse than ever’). Because of the heterogeneity of the total group, we repeated the analysis for the subgroup of patients without a history of non-traumatic knee symptoms, and for the subgroup of patients aged 12–35 years.

The analyses were performed using SPSS version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill., USA).

Results

Patients

presents the baseline characteristics of the 328 patients who participated in this study. Their mean age was 41.9 (SD: 15.7) years, and 56.4% were male.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the total group of patients and patients available at one and six-year follow-up.

At one-year follow-up 296 patients (90.2%), and at six-year follow-up 183 patients (55.8%), were still available for the study. The patients available at one and six-year follow-up showed no clinically relevant differences (). Also, patients available at six-year follow-up showed no significant difference compared with those available at one-year follow-up regarding their perceived recovery at one-year follow-up (OR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.53–1.48).

Course and prognosis

also presents the course of the patients regarding knee pain severity (NRS), Lysholm knee score and WOMAC index over the six-years of follow-up. The improvement of pain and WOMAC score in the first three months allows making a significant discrimination (P <0.05) between patients with persistent knee symptoms and those who were recovered at six-year follow-up.

Of the 296 patients available at one-year follow-up, 81 (27.4%) reported persistent knee symptoms. The characteristics at one-year follow-up of those patients with persistent knee symptoms are presented in . Patients who reported being recovered at one-year follow-up had a mean recovery period of 6.3 (SD: 10.5) months.

Table 2. Characteristics of patients with persistent knee symptoms at one and six-year follow-up.

Of the 183 patients available at six-year follow-up, 60 (32.8%) reported persistent knee symptoms. There was a positive relationship between having persistent knee symptoms at one-year follow-up and having persistent knee symptoms at six-year follow-up (OR: 11.0, 95% CI: 5.0–24.2).

The characteristics at six-year follow-up of those patients with persistent knee symptoms are presented in . Patients who reported to be recovered at six-year follow-up had a mean recovery period of 7.4 (SD: 13.1) months.

Of the subgroup of 185 patients without a history of non-traumatic knee symptoms available at one-year follow-up, 39 (21.1%) reported persistent knee symptoms at one-year follow-up. At six-year follow-up, 29 of the 120 available patients at six-year follow-up without a history of non-traumatic knee symptoms (24.2%) reported persistent knee symptoms. Patients without a history of non-traumatic knee symptoms who were recovered at six-year follow-up had a mean recovery period of 7.6 (SD: 13.6) months.

Of the subgroup of 108 patients aged 12–35 years available at one-year follow-up, 17 (15.7%) reported persistent knee symptoms at one-year follow-up. Of the 188 patients aged ≥ 36 years available at one-year follow-up, 64 (34.0%) reported persistent knee symptoms at one-year follow-up. At six-year follow-up, 13 of the 62 available patients aged 12–35 years (21.0%) and 47 of the 121 available patients aged ≥36 years (38.8%) reported persistent knee symptoms.

The mean recovery period of patients who were recovered at six-year follow-up was 7.8 (SD: 13.0) months for patients aged 12–35 years and 7.1 (SD: 13.3) months for patients aged ≥36 years.

Prognostic factors

presents the univariate associations between baseline characteristics and persistent knee symptoms at one and six-year follow-up. presents the multivariate associations between baseline characteristics and persistent knee symptoms at one-year follow-up.

Table 3. Univariable association between baseline characteristics and persistent knee symptoms at one and six-year follow-up.

Table 4. Multivariable associations between baseline characteristics and persistent knee symptoms at one-year follow-up.

The patient characteristics age and poor general health showed an independent association with persistent knee symptoms at one-year follow-up, with an AUC of 0.65.

From the symptom characteristics only history of non-traumatic knee symptoms remained in the model, with an AUC of 0.58. Adding the symptom characteristics to the patient characteristics the AUC increased by 0.03 to 0.68. All three variables remained in the model (P < 0.10). From physical examination absence of floating patella, laxity on the anterior drawer test and effusion of the fossa popliteal were independently associated, with an AUC of 0.64. Adding items from physical examination increased the AUC by 0.04 to 0.72. Effusion of the fossa popliteal was eliminated from the model (P > 0.10).

presents the multivariate associations between baseline characteristics and persistent knee symptoms at six-year follow-up. The patient characteristics age, BMI > 27 and non-skeletal co-morbidity showed an independent association with persistent knee symptoms at six-year follow-up, with an AUC of 0.73. From the symptom characteristics, self-reported crepitus of the knee and history of non-traumatic knee symptoms were independently associated, with an AUC of 0.70. Adding the symptom characteristic to the patient characteristics increased the AUC by 0.06 to 0.79.

Table 5. Multivariable associations between baseline characteristics and persistent knee symptoms at six-year follow-up.

All five variables remained in the model (P < 0.10). From physical examination, only laxity on the anterior drawer test remained in the model, with an AUC of 0.57. Adding items from physical examination increased the AUC by 0.03 to 0.82. All six variables remained in the model (P < 0.10).

Discussion

Main findings

The percentage of patients with persistent knee symptoms at one and six-year follow-up was similar, i.e. 27% and 33%, respectively. Patients without a history of non-traumatic knee symptoms and/or aged 12–35 years reported less frequent persistent knee symptoms compared with patients with a history of non-traumatic knee symptoms and/or aged ≥36 years, at both one and six-year follow-up. Of patients reporting persistent knee symptoms at one-year follow-up, 71% also reported these symptoms at six-year follow-up. Of patients who reported being recovered at one-year follow-up, 18% reported persistent knee symptoms at six-year follow-up (18%). The reasons for this could be due to recurrent trauma, other co-existing knee pathology (e.g. OA), and/or developing OA of the knee. It is known that traumatic knee symptoms are associated with the development of OA of the knee within 10–20 years after a knee injury.[Citation23] However, our follow-up period of six years might be too short to detect OA of the knee due to knee trauma. Nevertheless, many patients in the present study reported a history of non-traumatic knee symptoms and/or were aged ≥36 years. Therefore, their knee injury may have accelerated the development or progression of OA, because some traumatic knee lesions are associated with progression of knee OA.[Citation24,Citation25] In a subgroup of our traumatic patients, at one-year follow-up progression and new onset of signs of OA of the injured knee is visible on MRI.[Citation26]

Results in relation to existing literature

The assumed prognosis mentioned in the Dutch guideline ‘Traumatic knee symptoms in general practice’ is that most patients with a traumatic knee symptoms in general practice will be complaint free in a few weeks and can resume daily activities.[Citation2] Our results showed that this consensus-based prognosis is somewhat overestimated for patients with a traumatic knee complaint in general practice.

The general patient characteristics associated with persistent knee symptoms at one and six-year follow-up were as expected. They are also associated with persistent knee symptoms in patients with non-traumatic knee symptoms [Citation27–30] and/or in patients with other musculoskeletal disorders.[Citation19]

Other prognostic factors need more explanation. The presence of history of non-traumatic knee symptoms and self-reported crepitus of the knee as a prognostic factor indicate that patients with co-existing knee symptoms (most likely OA) had a higher risk of persistent knee symptoms. The absence of floating patella was associated with persistent knee symptoms at one-year follow-up only. Perhaps intra-articular effusion contributes to a better resilience of the knee injury. Laxity on the anterior drawer test was associated with persistent knee symptoms at one and six-year follow-up.

This could indicate that patients with anterior cruciate lesions lesion have a worse prognosis compared to other patients. However, this is in contrast to Wagemakers et al., who reported on a subgroup of patients with traumatic knee symptoms within this cohort (n = 134).[Citation31] The results showed no significant relationship between the type of lesion seen on baseline MRI and perceived recovery at one-year follow-up.

Perhaps the study population was too small to detect a different prognosis between anterior cruciate lesions and other lesions, or the type of anterior cruciate lesion and/or remaining function of the anterior cruciate after lesion might be important for recovery.

Boks et al. summarized the little information available on the course of traumatic knee symptoms from secondary care. They concluded that in most patients with cruciate lesions, improvement was reported within three months to one year but that doubt remains about functional recovery.[Citation3]

Strengths and limitations

One limitation of the present study is the relatively large loss to follow-up (44.2%) at six-year follow-up. However, the patients available at one and six-year follow-up did not appear to be a selected group of patients.

Another limitation was that we had a heterogeneous study population with all kinds of traumatic knee symptoms. However, all patients included in this study suffered from a knee injury with a clearly defined trauma mechanism. Investigating the course and prognostic factors by separate diagnoses might be preferable, but this requires a larger study population and a standardized diagnosis at baseline. However, in daily practice the GP does not have a clear diagnosis in patients with traumatic knee symptoms.

In this study, patients were recruited in general practice and therefore the results are not generalizable to persons with traumatic knee symptoms who did not seek health care at all or went to other healthcare providers such as a hospital emergency room or physiotherapy.

Conclusion

At one and six-year follow-up, traumatic knee symptoms in adolescents and adults in general practice still affect nearly one third of the patients. Patients who recover during follow-up had a mean recovery period of 7.4 months. Having persistent knee symptoms at one-year follow-up is an important predictor for having persistent knee symptoms at six-year follow-up. In addition, various prognostic factors assessed at baseline are associated with persistent knee symptoms at one and six-year follow-up. Patients without a history of non-traumatic knee symptoms and/or aged 12–35 years seem to have a better prognosis.

Funding

This study was funded by the department of General Practice of the Erasmus MC, Anna Fund and the insurance companies TRIAS, Zilveren Kruis, Achmea, OZ and partly by a programme grant of the Dutch Arthritis Foundation.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Supplementary_data_-_STROBE_Statement

Download PDF (28.2 KB)References

- van der Linden MW, Westert GP, de Bakker DH, Schellevis FG. Second national Dutch study: Complaints and disorders in general practice (in Dutch). Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research NIVEL. 2004;1–136.

- Belo JN, Berg HF, Klein Ikkink AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Traumatic knee disorders (in Dutch). Huisarts Wet. 2010;54:147–158.

- Boks SS, Vroegindeweij D, Koes BW, et al. Follow-up of posttraumatic ligamentous and meniscal knee lesions detected at MR imaging: Systematic review. Radiology. 2006;238:863–871.

- Kastelein M, Luijsterburg PA, Heintjes EM, et al. The 6-year trajectory of non-traumatic knee symptoms (including patellofemoral pain) in adolescents and young adults in general practice: A study of clinical predictors. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:400–405.

- van Middelkoop M, van Linschoten R, Berger MY, et al. Knee complaints seen in general practice: active sport participants versus non-sport participants. BMC Musculoskel Dis. 2008;19:36.

- Mallen CD, Peat G. Discussing prognosis with older people with musculoskeletal pain: A cross-sectional study in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:50.

- Heintjes EM, Berger MY, Koes BW, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Knee disorders in primary care: Design and patient selection of the HONEUR knee cohort. BMC Musculoskel Dis. 2005;6:45.

- Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, et al. Validation study of WOMAC: A health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to anti-rheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–1840.

- Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS, et al. Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS)—development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28:88–96.

- Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, et al. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 health survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1055–1068.

- Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83.

- Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;248:13–14.

- Tegner Y, Lysholm J. Rating systems in the evaluation of knee ligament injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;198:43–49.

- Swinkels-Meewisse EJ, Swinkels RA, Verbeek ALM, et al. Psychometric properties of the Tampa scale for kinesiophobia and the fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire in acute low back pain. Man Ther. 2003;8:29–36.

- Nelson E, Wasson J, Kirk J, et al. Assessment of function in routine clinical practice: Description of the COOP chart method and preliminary findings. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:55S–69S.

- Van Weel C. Functional status in primary care: COOP/Wonca charts. Disabil Rehabil. 1993;15:96–101.

- Hoppenfield S. Physical examination of the spine and extremities. East Norwalk (CT): Appleton Century Crofts; 1976.

- Reider B. The orthopaedic physical examination. Oxford: WB Saunders; 1999. pp. 202–245.

- Mallen CD, Peat G, Thomas E, et al. Prognostic factors for musculoskeletal pain in primary care: A systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57:655–661.

- Donders AR, van der Heijden GJ, Stijnen T, Moons KG. Review: A gentle introduction to imputation of missing values. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:1087–1091.

- Moons KG, Donders RA, Stijnen T, Harrell FE, Jr. Using the outcome for imputation of missing predictor values was preferred. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:1092–1101.

- van der Heijden GJ, Donders AR, Stijnen T, Moons KG. Imputation of missing values is superior to complete case analysis and the missing-indicator method in multivariable diagnostic research: A clinical example. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:1102–1109.

- Lohmander LS, Englund PM, Dahl LL, Roos EM. The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: Osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1756–1769.

- Berthiaume MJ, Raynauld JP, Martel-Pelletier J, et al. Meniscal tear and extrusion are strongly associated with progression of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis as assessed by quantitative magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:556–563.

- Sharma L, Eckstein F, Song J, et al. Relationship of meniscal damage, meniscal extrusion, malalignment, and joint laxity to subsequent cartilage loss in osteoarthritic knees. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1716–1726.

- Koster IM, Oei EH, Hensen JH, et al. Predictive factors for new onset or progression of knee osteoarthritis one year after trauma: MRI follow-up in general practice. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:1509–1516

- Belo JN, Berger MY, Koes BW, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Prognostic factors in adults with knee pain in general practice. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:143–151.

- Jinks C, Jordan KP, Blagojevic M, Croft P. Predictors of onset and progression of knee pain in adults living in the community. A prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:368–374.

- Thomas E, Peat G, Mallen C, et al. Predicting the course of functional limitation among older adults with knee pain: Do local signs, symptoms and radiographs add anything to general indicators? Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1390–1398.

- van der Waal JM, Bot SD, Terwee CB, et al. Course and prognosis of knee complaints in general practice. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:920–930.

- Wagemakers HP, Luijsterburg PA, Heintjes EM, et al. Outcome of knee injuries in general practice: 1-year follow-up. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60:56–63.