Abstract

Context: In Iran, conventional production methods of herbal oils are widely used by local practitioners. Administration of oils is rooted in traditional knowledge with a history of more than 3000 years. Scientific evaluation of these historical documents can be valuable for finding new potential use in current medicine.

Objective: The current study (i) compiled an inventory of herbal oils used in ancient and medieval Persia and (ii) compared the preparation methods and therapeutic applications of ancient times to current findings of medicinal properties in the same plant species.

Materials and methods: Information on oils, preparation methods and related clinical administration was obtained from ancient Persian documents and selected manuscripts describing traditional Persian medicine. Moreover, we investigated the efficacy of medicinal plant species used for herbal oils through a search of the PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar databases.

Results: In Iran, the application of medicinal oils date back to ancient times. In medieval Persian documents, 51 medicinal oils produced from 31 plant species, along with specific preparation methods, were identified. Flowers, fruits and leaves were most often used. Herbal oils have been traditionally administered via oral, topical and nasal routes for gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, and neural diseases, respectively. According to current investigations, most of the cited medicinal plant species were used for their anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties.

Conclusions: Medicinal oils are currently available in Iranian medicinal plant markets and are prepared using traditional procedures for desirable clinical outcomes. Other than historical clarification, the present study provides data on clinical applications of the oils that should lead to future opportunities to investigate their potential medicinal use.

Introduction

Oils are one of the most ancient forms of natural herbal medicines (Kasthuri et al., Citation2010). Since the beginning of civilization, herbal, animal and mineral medicaments have been used to treat illnesses (Rezaeizadeh et al., Citation2009), however, most remedies in traditional medical systems have focused on medicinal herbs (Gurav et al., Citation2011). These medicaments have been historically administered either individually or in combinations in the form of pills, powders, extractions, etc. (Kiyohara et al., Citation2004; Wadud et al., Citation2007). Medical and pharmaceutical manuscripts authored by medieval Persian practitioners present not only an accumulation of traditional medical systems, but also contain a collection of ingenious studies (Khaleghi Ghadiri & Gorji, Citation2004) that provide valuable information in the field of medicinal herb formulation. In fact, pioneering medieval practitioners, namely Rhazes (865–925 AD) and Avicenna (980–1037 AD), are credited as the founders of the golden age of Persian medical sciences which occurred from the eighth to seventeenth centuries (West, Citation2008; Zargaran et al., Citation2012a). Most current ethnopharmacological knowledge in Iran has been derived from historical manuscripts. An Attār is a traditional Iranian herbalist who dispenses medicinal plants and practices traditional methods. Mostly, being an Attār is a familial position, in which knowledge has been handed-down across many generations and continues to be widely used in the current era (Naghibi et al., Citation2005; Yesilada, Citation2005). In this regard, traditional knowledge of natural medicine recorded in historical manuscripts can help to unravel the ethnopharmacological roots of traditional Iranian concepts and herbal classifications.

Historical medical and pharmacological manuscripts describe various pharmaceutical applications of medieval Persian medicine. One of the known forms of application for therapeutic purposes via topical or systemic administration is medicinal oils prepared from numerous medicinal herbs (Avicenna, Citation1988; Heravi, Citation1765). The formulation and preparation of herbal oils are known as “Dohn” or the plural term “Adhaan” and described in a series of historical Persian pharmaceutical manuscripts, namely “Qarabadin” (pharmacopeia), which consists of medical texts on drug compounds, formulas and indications (Levey, Citation1966).

Medicinal oils are largely ignored and rarely investigated in contemporary medical research. However, the application of herbal oils and extracts for medical purposes originated and continues in traditional Chinese, Indian and Egyptian medicine (Shikov et al., Citation2009). Massage therapy using herbal oils continues to be practiced in several East Asian countries (Mullany et al., Citation2005). Moreover, aromatherapy with volatile oils has been shown to improve immunological and physiological conditions (Kuriyama et al., Citation2005).

Several herbal oils are easily prepared and continue to be used as practical therapeutic interventions in Iranian folk medicine. However, no acceptable relevant investigations have been performed on the efficacy, safety or toxicity of such pharmaceutical products. All traditional drugs and therapeutic approaches for using in current medicine should to be evaluated and standardized with current standards of pharmaceutics and medical approaches. To reach this aim, we should first have a clear view on traditional knowledge compared to current concepts. Therefore, the present review investigated common medicinal oils used in traditional Persian medicine (TPM) to derive the preparation methods, dosages and reported therapeutic approaches.

Method

We investigated surviving Persian medical and pharmaceutical manuscripts from the tenth to the eighteenth century AD, which included Canon of Medicine (Avicenna, Citation1025), book of Qarabadin-e-azam (Azamkhan, Citation1853), Qarabadin-e-ghaderi (Arzani, Citation1714), Qarabadin-e-kabir (Aghili Shirazi, Citation1772), Qarabadin-e-salehi (Heravi, Citation1765) and Tohfat ol Moemenin (Tonekaboni, Citation2007). It should be noted that these texts are used exclusively as references for the Iranian PhD program in traditional pharmacy (Ministry of Health and Medical Sciences Education, Citation2007). In these references, sections containing information on the preparation and administration of medicinal oils were evaluated and relevant data were collected, categorized and analyzed. Additionally, a short survey on some examples of medicinal oils from ancient Persia was included.

The scientific names of the plant species of the medicinal oils were authenticated using botanical textbooks, including the Dictionary of Medicinal Plants (Soltani, Citation2004), Popular Medicinal Plants of Iran (Amin, Citation2005), Pharmacographia Indica (Dymook, et al., Citation1893) and Indian Medicinal Plants (Khare, Citation2007). Additional reports on current pharmacological effects of the included medicinal herbs were derived from PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar databases to establish relationships between traditional knowledge and current findings.

Results and discussion

Examples of medicinal oil use in ancient Persia

The medical and pharmaceutical use of oils in Persia dates back to ancient times. Prior to 637 AD (Wiesehöfer, Citation2006) (entrance of Islam to Iran), Persia was ruled by three dynasties: Achaemenid (550–330 BC), Parthian (247 BC–224 AD) and Sassanid (224–637AD), which all have well-documented histories (Zargaran et al., Citation2012b). However, there is limited information concerning medical and pharmaceutical practices from these periods. One of the most important documents, Bondahesh, a Sassanid Pahlavi manuscript, classified all plant species into 11 groups, including oily herbs that were identified through their oily seeds (Dadegi, Citation2006). Examples of medicinal herbs mentioned in the Bondahesh include olive oil (Olea europaea L. (Oleaceae)), castor oil [Ricinus communis L. (Euphorbiaceae)] and hemp [Cannabis sativa L. (Cannabaceae)] (Dadegi, Citation2006; Biruni, Citation2004).

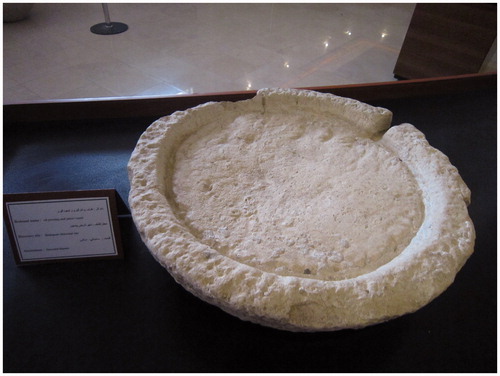

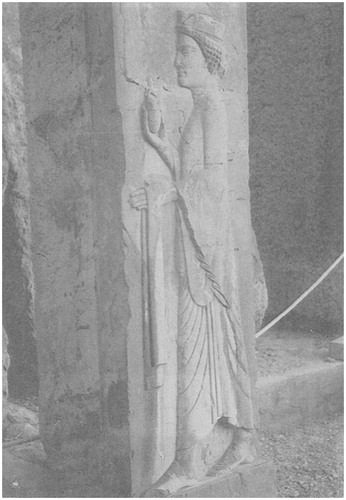

Remnants of a tool used for oil extraction from seeds, dating to the Sassanid period, was discovered in Bishapur (), an ancient city located in the Fars province of Iran. A design on a stone showing a man with an oil jar in one hand and a towel in the other () exists in Persepolis (the Achaemenid capital, 500 BC). However, this figure may represent the cosmetic application of oils, which was widely practiced in ancient Persia, especially as demulcent agents used after bathing (Mohagheghzadeh et al., Citation2011). Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) and labdanum oil (Cistus ladanifer L.) were used in the production of hand and face creams as early as 330 BC (Gershevich, Citation2006). Extraction of oil-soluble ingredients from medicinal plants was reported in ancient documents, such as lily oil extracts used as topical analgesics (Adhami et al., Citation2007).

Preparation and formulation of medicinal oils used in medieval Persia

Medieval Persian scholars and physicians recorded dosages of medicinal oils (dohn) based on methods attributed to Pythagoras and Socrates (Tonekaboni, Citation2007). They described medicinal oils and also the preparation methods and applications of the formulas.

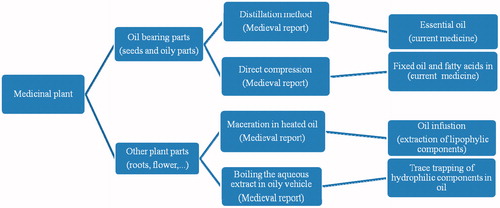

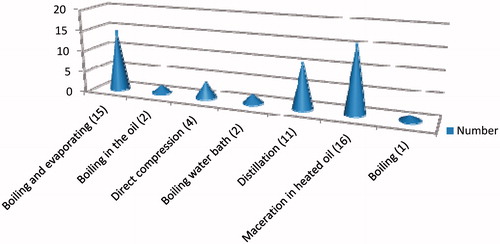

Generally, pharmaceutical dosages of medicinal oils were prepared by two primary methods: direct extraction from the herbs via compression of oil-bearing components or distillation of aromatic plants parts, or indirect, which involved the extraction of plants to prepare vegetable oils (Mikaili et al., Citation2012) (). In the latter group, soft, fragrant aerial parts such as flowers, leaves or fleshy fruits were soaked in traditionally prepared almond, sesame and olive oils, among others, and exposed to the sun or an artificial heat source for several days while replacing the spent parts with fresh ones until they are based on the color and aroma of the particular herb (maceration in heated oil) (Heravi, Citation1765; Avicenna, Citation1025). This method is comparable to modern-day enfleurage (Eltz et al., Citation2007). However, in the enfleurage process, animal fat was used. The above processes were often referred to as “the method of Greek practitioners” (Heravi, Citation1765). Currently, the oil infusion method is widely used by steeping plant parts containing the desired chemical compounds or flavors in an oily solvent (Jones, Citation2010).

Alternatively, rigid botanical parts such as roots and bark are traditionally decocted in water (aqueous extraction). In this type of oil preparation, the resulting extract is then boiled in an oily vehicle to evaporate the water portion (boiling and evaporating method) (Tonekaboni, Citation2007). Persian practitioners applied special methods to produce gummy derivatives such as Frankincense, in which gum was thoroughly dispensed in oil in a glass container, which was then submerged in boiling water until the gum fully dissolved in the oil (boiling water bath) (Heravi, Citation1765). The oil of aromatic gum resins such as myrrh was reportedly extracted via the distillation method (Aghili Shirazi, Citation1772).

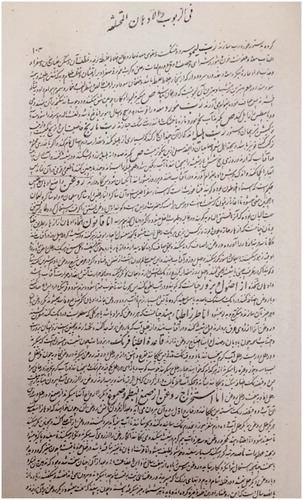

Approximately more than 50 different medicinal oils prepared by the above-mentioned methods were retrieved from pharmaceutical manuscripts describing TPM. is a photograph representing the first page of oil preparation chapter from the book of Qarabadin-e-salehi (Heravi, Citation1765). There, the author classically described the rules of oil preparation from different herbal parts through ways as mentioned. lists the plant species, as well as specific plant parts, preparation methods and literature references (Aghili Shirazi, Citation1772; Arzani, Citation1861; Avicenna, Citation1025; Heravi, Citation1765; Tonekaboni, Citation2007). The clinical use of herbal oils and the diseases that they purportedly ameliorate are listed in . Furthermore, current medical research pertaining to traditional applications of the oils and their active components is cited in .

Figure 4. From a copy of lithograph edition of Gharabadin Salehi. Start of the chapter of Dohn (Oil); about the rules related to the oil preparation (page 103).

Table 1. Medicinal plant species which were used to prepare traditional Persian oils.

Table 2. Comparing the pharmacological usage of traditional Persian medicinal oils with current findings.

Other than simple oils, compound herbal medicinal oils were reported in Persian pharmaceutical manuscripts, which also describe the inhibition of unwanted effects, reduction in potency, reinforcement of efficacy, improvement in taste, multiple therapeutic benefits and modification of undesirable effects using other medicinal herbs (Aghili Shirazi, Citation1772).

Medicinal oils (Adhaan) have been used in TPM for thousands of years to treat various ailments. Currently, many of these formulations are used as ethnomedical preparations by traditional practitioners in Iran (Mikaili et al., Citation2012). Fundamentally, herbal medicinal oils comprise essential and fixed oils depending on the part of the plant used as the source; however, the classification of herbal oils is not limited to these two groups. The enfleurage method or oil infusion, which is a simple means of extracting oil-soluble ingredients from plants, can be used in the traditional preparation method of herbal oils.

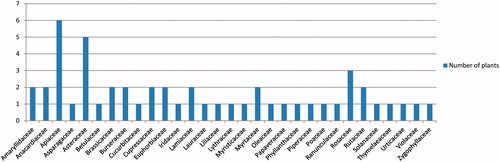

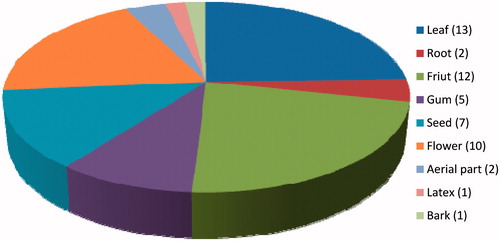

Of the 31 plant families noted in the historical documents, most medicinal plant species used to prepare oils belonged to families of Apiaceae (six varieties) and Asteraceae (five plant species) (). Also, most of the oils were derived from leaves, fruits and flower (). Distillation was the most common direct extraction method of medicinal oils, whereas the most common indirect methods were maceration in heated oil and boiling and evaporating ().

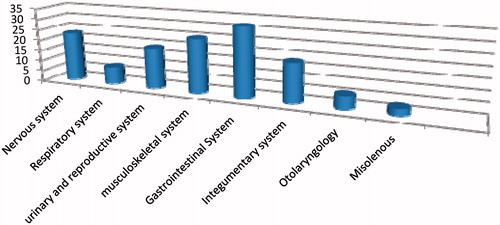

Medicinal oils have been traditionally used via topical, oral and even nasal routes to target particular areas of the body to combat specific ailments. Oils for gastrointestinal, respiratory, urinary and reproductive interventions were administered orally, while the nasal route was considered for disorders affecting the central nervous system. Topical forms were most often applied for nervous, musculoskeletal and integumentary afflictions. The use of medicinal oils for gastrointestinal disorders was most often cited in the TPM references (). Some traditional applications reported in the Persian literature correspond to current applications.

Out of the cited medicinal oils, 31 herbs comprised the main components and reportedly showed pharmacological effects in medieval Persian reports, in which analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects were the most relevant pharmacological effects. Most of the effects have been confirmed by recent in vitro or in vivo medical trials. Only one study on humans relevant to the traditional report was found (); hence, there is a lack of related human studies not only for oils, but also for other herbs and their dosages. In this regard, the oils cited in TPM can be good candidates for further investigation in the quest to discover new herbal drugs.

Notably, only a few pharmacological effects of essential oils noted in the ancient literature can be directly matched to current reports, such as clove and damask rose oil as analgesic agents (Daniel et al., Citation2009; Hajhashemi et al., Citation2010), cinnamon oil for its carminative and antimicrobial properties (Bouhdid et al., Citation2010; Harries et al., Citation1977) and the sedative effect of bitter orange (Carvalho-Freitas & Costa, Citation2002) ().

There are, however, several modern clinical reports documenting the effects of traditional medicinal oils obtained via direct compression, such as the anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects of terebinth oil (Giner-Larza et al., Citation2002; Orhan et al., Citation2012), antiepileptogenic and neuroprotective properties of black cumin oil (Kanter et al., Citation2006) and the xanthine oxidase inhibitory effect of almond oil polyphenols (Chen & Blumberg, Citation2008), which can be considered as evidence of these medicinal oils effectiveness. Overall, for these types of herbal oils, the medieval dosages are the same as that of the herbal metabolites.

Oil infusion of desirable parts of an herb (maceration in heated oil) was also popular with Persian practitioners. In this method, lipophilic constituents are infused into the oil, which acts as a nonpolar solvent, to produce concentrated herbal oils for aromatherapy (Jones, Citation2010). In this review, we identified 16 oils prepared by this method. However, we were unable to locate clinical research on oils of the investigated herbs mentioned in the historical documents. Therefore, oil infusion or maceration in heated oil can be considered as a newly rediscovered field, particularly for aromatherapy.

Several traditional oils were prepared by a boiling and evaporation method (Tonekaboni, Citation2007), in which chemical constituents in the aqueous phase become trapped in the oil phase following evaporation. Obviously, however, large amounts of heat-sensitive components extracted in the aqueous phase may decompose by overheating. As this method is not well accepted in current medicine, we found no credible evidence indicating the use of the form of preparation in contemporary science. However, for most constitutive herbs, relative effects were confirmed via current pharmacological methods.

Importantly, current methods typically employ ethanol, methanol or aqueous extractions, in which hydrophilic ingredients are initially extracted in water and the solution is then boiled. compares the respective scientific data on ethanol, methanol and aqueous extracts of related plants to that of medieval methods. Although aqueous extraction procedures for plant oils continue to be widely used, they are quite different to the historical methods (Campbell & Glatz, Citation2009).

For some of the oils cited in the historic literature that were prepared by oil infusion (maceration in heated oil), we considered clinical research which evaluated aqueous fractions. However, aqueous fractions certainly have no constitutes comparable to those extracted by the oil infusion process. In contrast, organic extractions with nonpolar solvents likely extract similar components. Regardless of the extraction process, we analyzed the pharmacological effects of the herbs cited in the historical documents. However, we did not find any scientific data for the 18 cited oils or their herbal constituents; although, two species Dorema ammoniacum D. Don. and Ferula persica Willd. (Apiaceae) are endemic to Iran and this limitation may be a reason for the lack of related clinical work. Nonetheless, those with no scientific data present good candidates for future clinical research.

Despite the advantages of herbal oils, such as ease of administration or rapid absorption by massaging, they might be less applicable in comparison to modern pharmaceuticals, due to potential complications in industrial preparation and standardization. Furthermore, the development of novel topical delivery systems, such as semisolid formulations, presents another reason for abandoning oils. Also, it should be noted that unsaturated fatty acids in plant oils can accelerate the oxidation process and complicate storage (Frega et al., Citation1999).

Essential oils are still prepared throughout Iranian medicinal plant markets and continue to be widely used in Persian folk medicine. Despite the large application of oils in various traditional medical systems, such as Chinese, Unani and Islamic medicine, pharmaceutical research is scarce and largely neglected by medical scientists.

Fixed and volatile oils are prepared via direct compression and distillation respectively, whereas oil infusion can capture various ingredients and secondary metabolites into an oily vehicle. In other circumstances, especially in “boiling and evaporating method”, herbal ingredients may form byproducts that possess pharmacological effects. Therefore, preliminary research on botanical therapeutics may be useful and perhaps preparation according to the exact ethnomedical method should be considered for desirable results. However investigation of the traditional formulations in a pharmaceutical view is one of the important approaches in ethnopharmacy (Heinrich, Citation2008). Furthermore, reformulation of ethno-products in current medicine needs in-depth investigations on traditional concepts based on historical studies as well as modern pharmaceutical and clinical evaluations.

Conclusion

Although various aspects of traditional medicinal herb production are observed in modern herbal therapy, considerable information on various traditional plant oil formulations remains unknown. Reports on a number of herbal oils can be found by searching through historical medical and pharmaceutical manuscripts. The oil form of natural medicaments presents a simple preparation method with desirable clinical applications. Other than historical clarifications, the present review provided a list of data on clinical remedies based on centuries of experience, and thus might be useful for future clinical trials.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no declarations of interest

References

- Aceto MD, Harris LS, Abood ME, Rice KC. (1999). Stereoselective μ- and δ-opioid receptor-related antinociception and binding with (+)-thebaine. Eur J Pharmacol 365:143–47

- Adhami HR, Mesgarpour B, Farsam H. (2007). Herbal medicine in Iran. Herbal Gram 74:34–43

- Aghili Shirazi SMH. (1772/1855). Qarabadin-e-Kabir. Tehran, Iran: Ostad Allah Qoli khan Qajar (in Persian)

- Ahmad F, Khan RA, Rasheed S. (1992). Study of analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity from plant extracts of Lactuca scariola and Artemisia absinthium. J Islamic Acad Sci 5:111–14

- Ali BH, Bashir AK, Tanira MO. (1995). Anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, and analgesic effects of Lawsonia inermis L. (henna) in rats. Pharmacology 51:356–63

- Alonso-Coello P, Zhou Q, Martinez-Zapata MJ, et al. (2006). Meta-analysis of flavonoids for the treatment of haemorrhoids. Br J Surg 93:909–20

- Al-Said MS, Ageel AM, Parmar NS, Tariq M. (1986). Evaluation of mastic, a crude drug obtained from Pistacia lentiscus for gastric and duodenal anti-ulcer activity. J Ethnopharmacol 15:271–8

- Amat N, Upur H, Blazekovic B. (2010). In vivo hepatoprotective activity of the aqueous extract of Artemisia absinthium L. against chemically and immunologically induced liver injuries in mice. J Ethnopharmacol 131:478–84

- Amin G. (2005). Popular Medicinal Plants of Iran. Tehran, Iran: Tehran University Press (in Persian)

- Arzani A. (1714/1861). Qarabadin-e-Ghaderi. Tehran, Iran: Mohammadi publication (Lithograph in Persian)

- Avicenna. (1025/1988). Canon of Medicine Vol. 5. Tehran, Iran: Soroosh Press (in Persian)

- Azamkhan MAK. (1853/2004). Qarabadin-e-Azam. Tehran, Iran: Intisharat va Amoozesh Enghelab Islami Press (in Persian)

- Bakhtiarian A, Rezai-Asl M, Sabour M, et al. (2012). The study of analgesic effects of hydroalcoholic extract of seed and crops of Anethum graveolens. Toxicol Lett 211:S209

- Behtash N, Kargarzadeh F, Shafaroudi H. (2008). Analgesic effects of seed extract from Petroselinum crispum (Tagetes minuta) in animal models. Toxicol Lett 180:127–8

- Bernard SB, Olayinka OA. (2010). Search for a novel antioxidant, antiinflammatory/analgesic or anti-proliferative drug: Cucurbitacins hold the ace. J Med Plants Res 4:2821–6

- Bidkar JS, Bhujbal MD, Ghanwat DD, Dama GY. (2011). Anthelmientic activity of Citrus aurantium Linn. Int J Pharmaceut Res Dev 3:69–72

- Biruni A. (10th century AD/2004). Al Seydaneh fi al Teb. Tehran, Iran: University Press (in Persian)

- Bouhdid S, Abrini J, Amensour M, et al. (2010). Functional and ultrastructural changes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus cells induced by Cinnamomum verum essential oil. J Appl Microbiol 109:1139–49

- Campbell KA, Glatz CE. (2009). Mechanisms of aqueous extraction of soybean oil. J Agric Food Chem 57:10904–12

- Carvalho-Freitas MIR, Costa M. (2002). Anxiolytic and sedative effects of extracts and essential oil from Citrus aurantium L. Biol Pharm Bull 25:1629–33

- Chen CYO, Blumberg JB. (2008). In vitro activity of almond skin polyphenols for scavenging free radicals and inducing quinone reductase. J Agric Food Chem 56:4427–34

- Conforti F, Sosa S, Marrelli M, et al. (2008). In vivo anti-inflammatory and in vitro antioxidant activities of Mediterranean dietary plants. J Ethnopharmacol 116:144–51

- Dadegi F. (9th century AD/2006). Bondahesh. Tehran, Iran: Tous Press (in Persian)

- Daniel AN, Sartoretto SM, Schmidt G, et al. (2009). Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive activities A of eugenol essential oil in experimental animal models. Rev Brasil Farmacog 19:212–17

- Dymook W, Warden CJH, Hooper D. (1893). Pharmacographica Indica. London, Iran: Kegan Paul

- Eltz T, Zimmermann Y, Haftmann J, et al. (2007). Enfleurage, lipid recycling and the origin of perfume collection in orchid bees. Proc Royal Soc B: Biol Sci 274:2843–8

- Ezeja MI, YS O. (2011). Nti-nociceptive activities of the methanol leaf extract of Nicotiana tabacum (Linn). African J Biomed Res 13:149–52

- Fattorusso E, Lanzotti V, Taglialatela-Scafati O, Cicala C. (2001). The flavonoids of leek, Allium porrum. Phytochemistry 57:565–9

- Frega N, Mozzon M, Lercker G. (1999). Effects of free fatty acids on oxidative stability of vegetable oil. J Amer Oil Chem Soc 76:325–9

- Gauthaman K, Adaikan PG, Prasad RNV. (2002). Aphrodisiac properties of Tribulus terrestris extract (Protodioscin) in normal and castrated rats. Life Sci 71:1385–96

- Gershevich I. (2006). Cambridge History of Iran (Achaemenid Empire). Translated by Saghebfar M. Tehran, Iran: Amirkabir (in Persian)

- Gholamnezhad Z, Boskabady MH, Iranshahi M, Bayrami G. (2011a). Dose asafoetida (Ferula assafoetida oleo-gum-resin) extract has relaxant effects on guinea-pig tracheal chains. Clin Biochem 44:S344–5

- Gholamnezhad Z, Byrami G, Boskabady MH, Iranshahi M. (2011b). Possible mechanism(s) of the relaxant effect of asafoetida (Ferula assa-foetida) oleo-gum-resin extract on guinea-pig tracheal smooth muscle. Avicenna J Phytomed 2:10–16

- Giner-Larza EM, Manez S, Giner RM, et al. (2002). Anti-inflammatory triterpenes from Pistacia terebinthus galls. Planta Med 68:311–15

- Gurav N, Solanki B, Pandya K, Patel P. (2011). Physicochemical and antimicrobial activity of single herbal formulation- capsule, containing Emblica officinalis gaertn. Int J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci 3:383–6

- Hajhashemi V, Ghannadi A, Hajiloo M. (2010). Analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of Rosa damascena hydroalcoholic extract and its essential oil in animal models. Iranian J Pharmaceut Res 9:163–8

- Harries N, James KC, Pugh WK. (1977). Antifoaming and carminative actions of volatile oils. J Clin Pharm Therap 2:171–7

- Heinrich M. (2008). Ethnopharmacy and natural product research; Multidisciplinary opportunities for research in the metabolomic age. Phytochem Lett 1:1–5

- Heravi MG. (1765). Qarabadin-e-Salehi. Tehran, Iran: Dar-ol-khalafeh (Litograph in Persian)

- Hosseinzadeh H, Noraei NB. (2009). Anxiolytic and hypnotic effect of Crocus sativus aqueous extract and its constituents, crocin and safranal, in mice. Phytother Res 23:768–74

- Ilhan A, Gurel A, Armutcu F, et al. (2005). Antiepileptogenic and antioxidant effects of Nigella sativa oil against pentylenetetrazol-induced kindling in mice. Neuropharmacology 49:456–64

- Jabbar A, Khan M, Iqbal Z. (2006). In vitro anthelmintic activity of Trachyspermum ammi seeds. Pharmacog Mag 2:126–9

- Jain NK, Kulkarni SK. (1999). Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of Tanacetum parthenium L. extract in mice and rats. J Ethnopharmacol 68:251–9

- Jayanthi M, Jyoti M. (2012). Experimental animal studies on analgesic and anti-nociceptive activity of Allium sativum (garlic) powder. The Indian J Res Rep Med Sci 2:1--7

- Jones M. (2010). The Complete Guide to Creating Oils, Soaps, Creams, and Herbal Gels for Your Mind and Body. Florida, USA: Atlantic Publishing Company

- Kanter M, Coskun O, Kalayc M, et al. (2006). Neuroprotective effects of Nigella sativa on experimental spinal cord injury in rats. Hum Exp Toxicol 25:127–33

- Kasthuri KT, Radha R, Jayshree N, et al. (2010). Standardization and in vitro anti-inflammatory studies of a poly herbal oil formulation. Res J Pharm Tech 3:792–4

- Khaleghi Ghadiri M, Gorji A. (2004). Natural remedies for impotence in medieval Persia. Int J Impot Res 16:80–3

- Khare C. (2007). Indian Medicinal Plants. New York: Springer

- Kiyohara H, Matsumoto T, Yamada H. (2004). Combination effects of herbs in a multi-herbal formula: Expression of juzen-taiho-to's immuno-modulatory activity on the intestinal immune system. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 1:83–91

- Kumar GR, Reddy KP. (1999). Reduced nociceptive responses in mice with alloxan induced hyperglycemia after garlic (Allium sativum Linn.) treatment. Indian J Exp Biol 37:662–6

- Kuriyama H, Watanabe S, Nakaya T, et al. (2005). Immunological and psychological benefits of aromatherapy massage. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2:179–84

- Lahlou S, Tahraoui A, Israili Z, Lyoussi B. (2007). Diuretic activity of the aqueous extracts of Carum carvi and Tanacetum vulgare in normal rats. J Ethnopharmacol 110:458–63

- Levey M. (1966). The Medical Formulary or Aqrabadhin of Al-Kindi. Wisconsin, USA: University of Wisconsin Press

- Liakopoulou-Kyriakides M, Tsatsaroni E, Laderos P, Georgiadou K. (1998). Dyeing of cotton and wool fibres with pigments from Crocus sativus – Effect of enzymatic treatment. Dyes Pigments 36:215–21

- MacKay D. (2001). Hemorrhoids and varicose veins: A review of treatment options. Altern Med Rev 6:126–40

- Mikaili P, Shayegh J, Sarahroodi S, Sharifi M. (2012). Pharmacological properties of herbal oil extracts used in Iranian traditional medicine. Adv Environ Biol 6:153–8

- Ministry of Health and Medical Sciences Education. (2007). Program Book of Ph.D Degree in Traditional Persian Pharmacy. Tehran, Iran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education (Persian)

- Mohagheghzadeh A, Zargaran A, Daneshamuz S. (2011). Cosmetic sciences from ancient Persia. Pharm Hist (Lond.) 41:18–23

- Mullany LC, Darmstadt GL, Khatry SK, Tielsch JM. (2005). Traditional massage of newborns in Nepal: Implications for trials of improved practice. J Trop Pediatr 51:82–6

- Naghibi F, Mosaddegh M, Mohammadi Motamed S, Ghorbani A. (2005). Labiatae family in folk medicine in Iran: From ethnobotany to pharmacology. Iranian J Pharmaceut Res 4:63–79

- Nogueira JC, Diniz MF, Lima EO. (2008). In vitro antimicrobial activity of plants in Acute Otitis Externa. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 74:118–24

- Orhan IE, Senol FS, Gulpinar AR, et al. (2012). Neuroprotective potential of some terebinth coffee brands and the unprocessed fruits of Pistacia terebinthus L. and their fatty and essential oil analyses. Food Chem 130:882–8

- Pillai NR, Lillykutty L. (1991). Anti-diarrhoel potential of Myristica frangrans seed extracts. Anc Sci Life 11:74–7

- Raghav SK, Gupta B, Agrawal C, et al. (2006). Anti-inflammatory effect of Ruta graveolens L. in murine macrophage cells. J Ethnopharmacol 104:234–9

- Rezaeizadeh H, Alizadeh M, Naseri M, Shams Ardakani MR. (2009). The traditional Iranian medicine point of view on health and disease. Iranian J Public Health 38:169–72

- Rossi A, Di Paola R, Mazzon E, et al. (2009). Myrtucommulone from Myrtus communis exhibits potent anti-inflammatory effectiveness in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 329:76–86

- Sayyah M, Hadidi N, Kamalinejad M. (2004). Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity of Lactuca sativa seed extract in rats. J Ethnopharmacol 92:325–9

- Seddiek SA, Ali MM, Khater HF, El-Shorbagy MM. (2011). Anthelmintic activity of the white wormwood, Artemisia herba-alba against Heterakis gallinarum infecting Turkey poults. J Medl Plants Res 5:3946–57

- Seddik K, Nadjet I, Abderrahmane B, et al. (2010). Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of extracts from Artemisia herba alba Asso. leaves and some phenolic compounds. J Med Plants Res 4:1273–80

- Shikov AN, Pozharitskaya ON, Makarova MN. (2009). New technology for preparation of herbal extracts and soft halal capsules on its base. American-Eurasian J Sustainable Agric 3:130–4

- Soltani A. (2004). Dictionary of Medicinal Plants. Tehran, Iran: Arjmand Press (in Persian)

- Tahri A, Yamani S, Legssyer A, et al. (2000). Acute diuretic, natriuretic and hypotensive effects of a continuous perfusion of aqueous extract of Urtica dioica in the rat. J Ethnopharmacol 73:95–100

- Tavares L, McDougall GJ, Fortalezas S, et al. (2012). The neuroprotective potential of phenolic-enriched fractions from four Juniperus species found in Portugal. Food Chem 135:562–70

- Thangam C, Dhananjayan R. (2003). Antiinflammatory potential of the seeds of Carum Copticum Linn. Indian J Pharmacol 35:388–91

- Tonekaboni H. (1670/2007). Tohfat ol Momenin. Tehran, Iran: Nashre shahr Press (in Persian)

- Twaij HAA, Elisha EE, Khalid RM. (1989). Analgesic studies on some Iraqi medicinal plants part II. Pharm Biol 27:109–12

- Venancio AM, Onofre AS, Lira AF, et al. (2011). Chemical composition, acute toxicity, and antinociceptive activity of the essential oil of a plant breeding cultivar of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.). Planta Med 77:825–9

- Wadud A, Prasad PV, Rao MM, Narayana A. (2007). Evolution of drug: A historical perspective. Bull Indian Inst Hist Med Hyderabad 37:69–80

- West JB. (2008). Ibn al-Nafis, the pulmonary circulation, and the Islamic golden age. J Appl Physiol 105:1877–80

- Wiesehöfer J. (2006). Ancient Persia. New York: St Martine’s Press

- Williams CA, Harborne JB, Geiger H, Hoult JRS. (1999). The flavonoids of Tanacetum parthenium and T. vulgare and their anti-inflammatory properties. Phytochemistry 51:417–23

- Yesilada E. (2005). Past and future contributions to traditional medicine in the health care system of the Middle-East. J Ethnopharmacol 100:135–7

- Yucel I, Guzin G. (2008). Topical henna for capecitabine induced hand-foot syndrome. Invest New Drugs 26:189–92

- Zargaran A, Mehdizadeh A, Zarshenas MM, Mohagheghzadeh A. (2012a). Avicenna (980–1037 AD). J Neurol 259:389–90

- Zargaran A, Mehdizadeh A, Yarmohammadi H, Mohagheghzadeh A. (2012b). Zoroastrian priests: Ancient Persian psychiatrists. Am J Psych 169:255

- Zhou L, Satoh K, Takahashi K, et al. (2009). Re-evaluation of anti-inflammatory activity of mastic using activated macrophages. In Vivo 23:583–9