Abstract

Objective. To determine the cost-effective operative strategy for coronary artery bypass surgery in patients above 70 years. Design. Randomized, controlled trial of 900 patients above 70 years of age subjected to coronary artery bypass surgery. Patients were randomized to either on-pump or off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery. Data on direct and indirect costs were prospectively collected. Preoperatively and six months postoperatively, quality of life was assessed using EuroQol-5D questionnaires. Perioperative in-hospital costs and costs of re-intervention were included. Results. The Summary Score of EuroQol-5D increased in both groups between preoperatively and postoperatively. In the on-pump group, it increased from 0.75 (0.16) (mean (SD)) to 0.84 (0.17), while the increase in the off-pump group was from 0.75 (0.15) to 0.84 (0.18). The difference between the groups was 0.0016 QALY and not significantly different. The mean costs were 148.940 D.Kr (CI, 130.623 D.Kr–167.252 D.Kr) for an on-pump patient and 138.693 D.Kr (CI, 123.167 D.Kr–154.220 D.Kr) for an off-pump patient. The ICER base-case point estimate was 6,829,999 D.Kr/QALY. The cost-effectiveness acceptability curve showed 89% probability of off-pump being cost-effective at a threshold value of 269,400 D.Kr/QALY. Conclusions. Off-pump surgery tends to be more cost-effective than on-pump surgery. Long-term comparisons are warranted.

Introduction

Coronary artery bypass surgery is a well-validated treatment, offering improved survival and quality of life to patients with ischemic heart disease (Citation1). The operation is most often performed using cardiopulmonary bypass (conventional coronary artery bypass, CCABG) offering to the surgeon an immobilized heart, a bloodless field, and stable hemodynamic conditions. During the last two decades, an alternative technique of off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery (OPCAB) has been popularized. A large majority of patients in need of coronary revascularization can be operated using either technique. A number of randomized, controlled trials have shown similar clinical results mainly when the two techniques are applied to younger patients with low co-morbidity (Citation2–9). Recently, we (Citation10) and others (Citation11) found a similar equivalence of clinical results in elderly patients.

In 2009, an estimated 416.000 coronary artery bypass procedures were performed in the United States alone (Citation1). In view of sparse health care resources, cost-effectiveness of the procedures is of great importance. Previous studies have documented that OPCAB is more cost-effective than CCABG when performed on younger patients (Citation7–8,Citation12–15). However, in an ageing population in the industrialized world, coronary surgery is increasingly being performed in elderly patients, and resource utilization in this group may be different. We, therefore, wanted to assess the relative cost-effectiveness of CCABG versus OPCAB in a randomized study of elderly patients. The present paper provides an economic evaluation conducted as part of the DOORS study, including health care costs and self-reported, health-related quality of life (Citation10).

Material and methods

DOORS study

Nine-hundred patients above 70 years of age who were to undergo a coronary artery bypass operation were included in an open, randomized, controlled trial. Inclusion of patients was performed between January 2005 and November 2008 at the Dept. of Cardio-thoracic Surgery, Odense University Hospital, Dept. of Cardiac Surgery, Gentofte Hospital, Dept. of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Aalborg Hospital, Aarhus University Hospital, and Dept. of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery, Skejby Hospital, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark. Exclusion criteria included the following: patients unable to understand given information or reluctant to participate, re-do cardiac surgery, the operation not technically feasible using both procedures, and inclusion not possible for logistic reasons. The DOORS investigators are listed in Appendix 1.

All participating surgeons were consultants and experienced in CCABG and multi-vessel OPCAB surgery. The patients gave written consent after written and oral information. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee and registered at www.ClinicalTrials.Gov (Registration number, NCT00123981). On-line randomization was applied. Anaesthesia, cardiopulmonary bypass, surgery and postoperative care were performed according to the detailed protocols. The primary end point for which the power calculations were performed was a combined endpoint of death, stroke, or myocardial infarction. These primary results have been reported earlier (Citation10).

Before and six months after surgery, the participating patients were asked to fill in the EuroQol/EQ5D, Danish version. Six-month follow-up of the survival was performed through the Danish National Registry. More details of the study protocol have been reported earlier (Citation16).

Sources of cost data

A detailed set of patient-specific data was prospectively collected. The use of hospital resources was recoded as time in theatre, use of disposables and reusable equipment, use of blood products, length of stay in ICU, and length of the stay in standard ward. Before the beginning of patient inclusion, the heads of the participating surgical and anaesthetic departments were asked to fill in a questionnaire concerning the typical use of staff for an OPCAB and a CCABG operation, respectively. This questionnaire was again filled in after inclusion of half of the patients in order to assess whether practice had changed. For each operation, the duration of the operation and the use of equipment were prospectively recorded for each individual patient. Prices of equipment and gross wages for staff per effective hour of labour were collected to estimate unit costs. Data on annual wages of staff members involved in the procedures were retrieved from the involved surgical and anaesthetic departments, and from the accounting departments of the hospitals involved. Prices supplied from Aarhus University Hospital and Odense University Hospital for time at standard ward or ICU were applied to the calculations.

Patient's contact to Danish Hospitals, including new admissions and outpatient visits, as well as their contact to family physicians and prescription medicine was assessed using the Danish National Registry of Patients and data from the national health insurance. Standard tariffs of outpatient visits and time at standard ward or ICU were applied to the calculations.

National diagnosis-related group (DRG) tariffs were applied when comparing the costs of secondary admissions and of procedures (Citation17).

Data analysis and presentation

Analysis was performed according to the principle of intention-to-treat. Main outcome measures were quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs). The gain of QALY between preoperatively and six months postoperatively was calculated from the Danish EuroQol-5D questionnaire. Previously published Danish Time Trade-off values were applied (Citation18). Costs were calculated by multiplying the unit cost for each type of resource usage and the used amount of resources. Only marginal costs were calculated as costs that did not differ between the two alternatives were not included; that is, all hospital costs before the date and time of inclusion were not a part of the calculated total mean costs of either CCABG or OPCAB. The perspective was national health care and cost data comprised hospital costs (cost of initial stay including surgery, intensive care unit and bed department, re-admissions and outpatient visits), costs at general practitioners, other specialists, and of prescription medicine. ICER represents the price for gaining an extra QALY using one technology instead of the other. Only patients for whom a complete set of data was available were included in the analysis. Patients who died during the follow-up were assigned the EQ-5D value 0 at the time of death (Citation19) and costs according to their actual patient pathway. All unit costs were collected using the currency Danish Krone (D.Kr) for the year 2010 (exchange rate, 100 Euro = 746 D.Kr.).

Point estimates of costs and QALYs were calculated as bias-corrected non-parametric bootstrapping estimates (1000 replications), and QALYs were adjusted for baseline differences in EQ-5D score (Citation20). The standard deviation of the incremental costs and QALYs were assessed from 4000 bootstrap replications of the original data set (complete cases). From these bootstrap replications, the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve was constructed.

Results

Baseline data of the patients included in the analysis are given in . No statistically significant difference was detected between the CCABG and OPCAB groups with regard to age or major co-morbidity. The mean age of the participating patients was 75 years, and a large majority had triple-vessel disease. Corresponding data for the whole group of 900 included patients have been published earlier (Citation10).

Table I. Baseline clinical data.

Follow-up was complete with regard to mortality.During the six months follow-up period, 21 patients belonging to the CCABG group and 19 belonging to the OPCAB group died (p = ns).

Of the 900 randomized patients, 779 had a complete data set for cost-effectiveness. The main reason for incomplete data was unwillingness or incapability of the patient to fill in the EuroQol questionnaire at six-month follow-up (n = 79), .

Figure 1. Study flow chart: CCABG, conventional coronary artery bypass grafting; OPCAB, Off-pump coronary artery bypass.

The Summary Score of EQ-5D increased in both groups between preoperatively and postoperatively. In the CCABG-group, it increased from 0.75 (0.16) (mean (SD)) to 0.84 (0.17), while the increase in the OPCAB-group was from 0.75 (0.15) to 0.84 (0.18). In both the cases, this increase was statistically significant, whereas the difference between the groups was 0.0016 QALY and not significantly different.

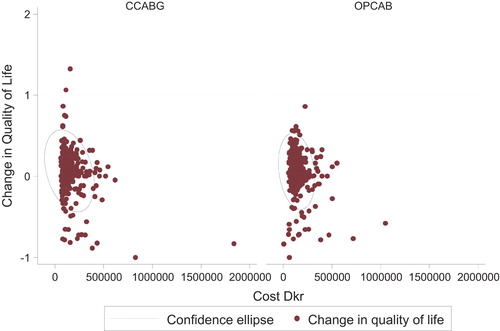

Hourly theatre costs of staff for the CCABG and OPCAB operations are given in , and the total six months costs are summarized in . The mean total costs were 148.940 D.Kr (CI, 130.623 D.Kr–167.252 D.Kr) for a CCABG patient and 138.693 D.Kr (CI, 123.167 D.Kr–154.220 D.Kr) for an OPCAB patient. Differences in costs and change in QALYs for each patient belonging to the OPCAB or CCABG groups are shown in . The most important differences included longer hospital stay, more costs of secondary admissions, and more costly theatre equipments in the CCABG group compared with those in the OPCAB group. The ICER base-case point estimate was 6,829,999 D.Kr/QALY.

Figure 2. Differences in costs and quality-adjusted years of life after CCABG and OPCAB surgeries. Costs are given as D.Kr. CCABG, conventional coronary artery bypass grafting and OPCAB, Off-pump coronary artery bypass.

Table IIa. Hourly theatre costs of OPCAB and CCABG (D.Kr).

Table IIb. Health-related costs of CCABG or OPCAB at six-month follow-up (D.Kr).

Secondary admissions during the first six months after surgery were defined as other admissions than the primary admission during which the operation was performed. This included admission to another hospital immediately as a result of transfer from the cardiac surgery centre as well as other admissions to a Danish hospital during the six-month follow-up. In Denmark, patients are often transferred to a more local hospital for further mobilization a few days after surgery rather than staying at the cardiac surgical centre until being ready for discharge. Among the patients randomized for CCABG, 293 of the 390 complete cases had secondary admissions. In the group randomized to OPCAB, 298 of 389 complete cases were readmitted within six months. The mean costs of secondary admissions divided into main ICD-10 diagnosis groups showed that the main difference consisted of higher costs in the CCABG-group in connection with secondary admissions under cardiac or pulmonary diagnoses.

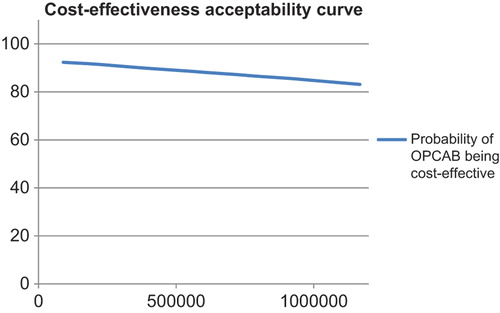

A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve, taking into account the statistical error of cost-effectiveness and QALYs, is shown in . It shows an approximately 89% probability of OPCAB being more cost-effective at a societal willingness to pay threshold value of 269,400 D.Kr/QALY corresponding to the threshold value of 30,000 GB£/ QALY used by the British National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (100 GB£ = 898 D.Kr) (Citation21).

Discussion

This is the first trial to give a detailed comparative economic assessment of CCABG and OPCAB surgeries specifically in elderly patients. Previous studies have documented that OPCAB is less expensive than CCABG in younger patients with lower perioperative risks (Citation3,Citation7,Citation12). The present study confirms this finding to be true in elderly patients with higher co-morbidity.

In earlier studies, some investigators assumed that the hourly costs of theatre staff were identical when performing the two operations (Citation14). Our costing study showed a difference in hourly theatre costs mainly due to the routine of anaesthetic nurses administering anaesthesia without the presence of a senior anaesthetist during cardiopulmonary bypass. When performing OPCAB operations, the senior anaesthetist was present during the entire procedure. This difference exceeded the oppositely directed difference between the price of the perfusionist being present for the entire procedure at CCABG or being on call for OPCAB operations in case of need for conversion. This difference reflects current practice in the four participating centres and may be different in other countries with different training, competence, and salaries of the participating staff.

While some earlier investigators (Citation8,Citation15) only included costs at discharge from the initial admission, the Octopus study (Citation12) recorded costs concerning readmission for cardiac or cerebrovascular disease. We chose to include all admissions and outpatient visits during the first postoperative six months in the present analysis. This choice was based on the evidence that other complications, including gastrointestinal bleeding and chest infections, may be associated with the use of cardiopulmonary bypass (Citation22–23).

In line with the earlier studies, we found a tendency towards shorter initial hospital stay after OPCAB than after CCABG as well as a trend towards shorter stay in intensive care unit (Citation3,Citation7,Citation12). The difference in the costs of secondary admissions contributed approximately half of the mean difference in costs between OPCAB and CCABG groups. Most of these secondary admissions were made under cardiac and pulmonary diagnoses. These numbers include admissions after transfer to another hospital for mobilization immediately after the admission to cardiac surgery. In Denmark, patients are often transferred to a local hospital for further mobilization a few days after surgery rather than staying at the cardiac surgical centre until being ready for discharge. In contrast to our present findings, earlier investigators found a significantly longer stay at hospital ward after CCABG than after OPCAB even when the discharging doctor was blinded to the procedure that had been performed (Citation7). It is likely that the difference, we find in the costs of secondary admissions, likewise, represents a slightly more difficult recovery after CCABG.

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for CCABG, as compared with OPCAB in the present study, is even higher than that previously reported for younger patients (Citation12). It is also substantially above the societal willingness-to-pay for a quality-adjusted year of life gained, and the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve showed a high probability of OPCAB being more cost-effective than CCABG.

Although we report the results of a multicentre clinical, randomized, controlled trial, the trial protocol was closely matched with daily, clinical practice at the participating centres. We, therefore, consider the results as “real life” data, reflecting genuine differences in hospital costs between CCABG and OPCAB.

With the large number of coronary artery bypass procedures being performed, savings may be substantial if OPCAB were to be used to a wider extent than what is presently the case. However, long-term follow-up of clinical outcome and societal costs are still warranted.

Limitations of study

So far, the analysis has been limited to a relatively short follow-up of six months. Although the direct hospital costs associated with the operations are included, a longer follow-up is needed to assess the societal costs and costs of secondary admissions as well as the long-term influence on health-related quality of life. Our earlier analysis showed that the patients randomized to OPCAB received a lower number of bypass grafts than the patients randomized to CCABG (Citation10). Theoretically, this may lead to a higher need of secondary admissions and interventions in the longer term.

Also, in this analysis, we aimed to assess only the difference in costs between the two procedures. Therefore, no attempt was made to include all costs that were expected to be identical in the two groups, including costs of preoperative coronary angiograms and of preoperative stay at the hospital during diagnostic work-up. Moreover, we included only marginal costs from a health care sector perspective, and not costs in other sectors.

Finally, the costs reported reflect the current practice, the level of wages, and the access to readmission in the four participating Danish centres. These variables are bound to be different in other health care systems, and the data should be interpreted in accordance with this condition.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no declarations of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

The Danish Heart Foundation, the Danish Centre for Health Technology Assessment, The Danish Research Council for Health Sciences, Tove and John Girott's Foundation, Medtronic, Guidant, Getinge AB supported the DOORS Study.

References

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics–2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–e220.

- van Dijk D, Spoor M, Hijman R, Nathoe HM, Borst C, Jansen EW, et al. Cognitive and cardiac outcomes 5 years after off-pump vs on-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA. 2007;297:701–8.

- Angelini GD, Taylor FC, Reeves BC. Early and midterm outcome after off-pump and on-pump surgery in Beating Heart Against Cardioplegic Arrest Studies (BHACAS 1 and 2): a pooled analysis of two randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2002;359:1194–9.

- Czerny M, Baumer H, Kilo J, Zuckermann A, Grubhofer G, Chevtchik O, et al. Complete Revascularization in coronary artery bypass grafting with and without cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:165–9.

- Légaré J-F, Buth KJ, King S, Wood J, Sullivan JA, Hancock Friesen C, et al. Coronary bypass surgery performed off pump does not result in lower in-hospital morbidity than coronary artery bypass grafting performed on pump. Circulation. 2004;109:887–92.

- Lingaas PS, Hol PK, Lundblad R, Rein KA, Vatne K, Smith HJ, et al. Clinical and angiographic outcome of coronary surgery with and without cardiopulmonary bypass: a prospective randomized trial. Heart Surg Forum. 2004;7:37–41.

- Puskas JD, Williams WH, Mahoney EM, Huber PR, Block PC, Duke PG, et al. Off-pump vs conventional coronary artery bypass grafting: early and 1 year graft patency, cost, and quality-of-life outcomes. A randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1841–9.

- Straka Z, Widimsky P, Jirasek K, Stros P, Votava J, Vanek T, et al. Off-pump versus on-pump coronary surgery: final results from a prospective randomized study PRAGUE-4. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:789–93.

- Shroyer AL, Grover FL, Hattler B, Collins JF, McDonald GO, Kozora E, et al. On-pump versus off-pump coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1827–37.

- Houlind K, Kjeldsen BJ, Madsen SN, Rasmussen BS, Holme SJ, Nielsen PH, et al. On-pump versus off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery in elderly patients. Results from the Danish on-pump vs. off-pump randomization study (DOORS). Circulation. 2012;125:2431–9.

- Møller CH, Perko MJ, Lund JT, Andersen LW, Kelbaek H, Madsen JK, et al. No major differences in 30-day outcomes in high-risk patients randomized to off-pump versus on-pump coronary bypass surgery. The best bypass surgery trial. Circulation. 2010;121:498–504.

- Nathoe HM, Dijk D, Jansen EWL, Suyker WJ, Diephuis JC, van Boven WJ, et al. A comparison of on-pump and off-pump coronary bypass surgery in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:394–402.

- Al-Ruzzeh S, Epstein D, George S, Bustami M, Ilsley C, Sculpher M, et al. Economic evaluation of coronary artery bypass grafting surgery with and without cardiopulmonary bypass: cost-effectiveness and quality-adjusted life years in a randomized controlled trial. Artif Organs. 2008;32:891–7.

- Ascoine R, Lloyd CT, Underwood MJ, Lotto AA, Pitsis AA, Angelini GD. Economic outcome of off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery: a prospective randomized study. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:2237–42.

- Lee JD, Lee SJ, Tsushima WT, Yamauchi H, Lau W, Popper J, et al. Benefits of off-pump bypass on neurologic and clinical morbidity: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:18–26.

- Houlind K, Kjeldsen BJ, Madsen SN, Rasmussen BS, Holme SJ, Schmidt TA, et al. The impact of avoiding cardiopulmonary by-pass during coronary artery bypass surgery in elderly patients: the Danish On-pump Off-pump Randomisation Study (DOORS). Trials. 2009;10:47.

- Ankjaer-Jensen A, Rosling P, Bilde L. Variable prospective financing in the Danish hospital sector and the development of a Danish case-mix system. Health Care Manag Sci. 2006;9:259–68.

- Wittrup-Jensen K, Lauridsen JT, Gudex C, Pedersen KM. Generation of a Danish TTO value set for EQ-5D health states. Scand J Public Health. 2009;37:459–66.

- Drummond MF, Schulper MJ, Torrance GW, O’Brien B, Stoddart GL. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1997.

- Manca A, Hawkins N, Schulper MJ. Estimating mean QALYs in trial-based cost-effectiveness analysis: the importance of controlling for baseline utility. Health Econ. 2005;14:487–96.

- Devlin N, Parkin D. Does nice have a cost effectiveness threshold and what other factors influence its decisions? Health Econ. 2004;13:437–452.

- Raja SG, Haider Z, Ahmad M. Predictors of gastrointestinal complications after conventional and beating heart coronary surgery. Surgeon. 2003;1:221–8.

- Cheng DC, Bainbridge D, Martin JE, Novick RJ. The evidence-based perioperative clinical outcomes research group. Does Off-pump coronary artery bypass reduce mortality, morbidity, and resource utilization when compared with conventional coronary artery bypass? A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:188–203.

Appendix 1. The DOORS study group.

The DOORS study group

Investigators:

Kim Houlind, M.D., Ph.D (Chairman), Bo Juul Kjeldsen M.D., Ph.D, Susanne Madsen M.D., Bodil Steen Rasmussen M.D., Ph.D, Susanne Holme M.D., Poul Erik Mortensen M.D.

Steering Committee:

Poul Erik Mortensen M.D. (Chairman), Vibeke Hjortdal MD, D.M.Sc., Ph.D, Gert Lerbjerg M.D., Uffe Niebuhr M.D., Soren Aggestrup, M.D., Susanne Holme M.D., Per Hostrup Nielsen M.D., Jorn Sollid M.D., Jorgen Videbæk M.D., D.M.Sc., Kim Houlind M.D., Ph.D

Ethical and safety committee:

Paul Sergeant, MD, Ph.D. (Chairman), Elisabeth Stahle, M.D., D.M. Sc, Patrick Wouters M.D.

End point committee:

Peter Kildeberg Paulsen M.D., D.M.Sc. (Chairman), Christian Hassager M.D., D.M.Sc., Ib Chr. Klausen M.D., D.M.Sc, Grethe Andersen M.D., D.M.Sc, Per Meden M.D., Boris Modrau M.D.

Statistical group:

Henrik Toft Sørensen M.D., D.M.Sc., Søren Paaske Johnsen, M.Sc. Ph.D., Niels Trolle Andersen M.Sc. Ph.D., Morten Fenger-Grøn, M. Sc.

Surgical group:

Jan Jesper Andreasen M.D., Ph.D., Poul Erik Haahr M.D., John Christensen M.D., Jens Grønlund M.D., Susanne Holme M.D., Per Hostrup Nielsen M.D., Mogens Harrits Jepsen M.D., Bo Juul Kjeldsen M.D., Ph.D, Susanne Madsen M.D., Poul Erik Mortensen M.D., Peter Pallesen M.D., Jørn Sollid M.D.

Invasive cardiology group:

Jan Ravkilde M.D., D.M.Sc., Jens Aaroe M.D., D.M.Sc., Peter Riis Hansen M.D., D.M.Sc., Henrik Steen Hansen M.D., D.M.Sc., Dorthe Dalsgaard, M.D., Henrik Munkholm, M.D.

Committee on Health Economics:

Lars Ehlers M.Sc., Ph.D., Søren Jepsen Bech, M.Sc., Kristian Kidholm M.Sc., Ph.D., Jørgen Lauridsen M.Sc., Ph.D.