Abstract

Objective: Cardiovascular implantable electronic device (CIED) infections are increasing in numbers. The objective was to review the clinical presentation and outcome in patients affected with CIED infections with either local pocket or systemic presentation. Design: All device removals due to CIED infection during the period from 2005 to 2012 were retrospectively reviewed. CIED infections were categorized as systemic or pocket infections. Treatment included complete removal of the device, followed by antibiotic treatment of six weeks. Results: Seventy-one device removals due to infection (32 systemic and 39 pocket infections) were recorded during the study period. Median follow-up time was 26 (IQR 9–41) months, 30 day and 12 month mortality were 4% and 14%, respectively. There was no long-term difference in mortality between patients with pocket vs. systemic infection (p = 0.48). During follow-up no relapses and two cases of new infections were noted (2.8%). Conclusions: CIED infection with systemic or pocket infection was difficult to distinguish in clinical presentation and outcome. Complete device removal and antibiotic treatment of long duration was safe and without relapses.

Introduction

The incidence of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIED) associated infection is rising [Citation1] because of increasing use of different CIED modalities. Worldwide, the use of more complex CIED’s such as biventricular pacemakers for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) and implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) [Citation2] along with the use of increased numbers of pacemaker leads in each patient has increased the risk of complications. CIED infections are associated with increased mortality [Citation3] and a need for prolonged hospitalization to ensure sufficient antibiotic treatment and device removal.

The diagnosis of CIED infections is often difficult. Moreover, attempts to distinguish between a local device pocket infection and a systemic response with positive blood cultures and lead vegetations, is usually difficult.[Citation4,Citation5] As the performance of the traditional Duke criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis are poor for the diagnosis of CIED associated infection, modified diagnostic criteria have been proposed.[Citation6–8] The optimal management of CIED infections remains uncertain, with treatment recommendations generally based on observation studies and expert opinions. Overall, complete device removal is recommended once CIED infection is recognized [Citation4,Citation9] due to unacceptable relapse rates and mortality if only antibiotic treatment is applied without device removal.[Citation8,Citation10] However, the optimal duration of antibiotic treatment after device removal is unknown and present guidelines and scientific statements recommend 4–6 weeks of antibiotic treatment and distinguish between systemic and pocket infections.[Citation4,Citation9,Citation11] But few previous studies have compared the different outcome of CIED infections with pocket vs. systemic infection presentation.

Methods

During the seven years period from April 2005 to September 2012 a retrospective search was done for all device removals performed at Rigshospitalet from April 2005 to September 2012. The removal of CIEDs for the Eastern part of Denmark is centralized at Rigshospitalet, covering approximately 2.1 million inhabitants, 37.5% of the total inhabitants in Denmark. Using the Danish diagnosis registry all device removals in the mentioned period was recognized, and using the local “PATS” database all device procedures were recorded. During the same period of time the total number of device implantations in this area was collected from the Danish Pacemaker Registry, the implantation count stopped march 2011 resulting in a 18 month follow up time from the latest procedure. The medical records of all patients who had undergone device removal were reviewed, and information was recorded on vital status, clinical symptoms and presentation, microbiological findings, blood test values and echocardiography results.

Treatment regimen

During this period of time we followed a modified protocol of treatment of CIED infection that were slightly modified from the ESC guidelines: All cases of CIED infection was treated with complete device and lead removal followed by four weeks of antibiotic treatment according to the bacteriology from blood, pocket and device leads. After this, a new device was implanted on the contra lateral side followed by another two weeks of antibiotic treatment, administered orally if possible. To analyse differences between patients affected with a local device pocket infection and systemic infections, as suggested by Baddour et al.,[Citation4] patients were divided into two groups as follows: Patients with signs of local pocket infection, but without positive blood cultures or lead vegetations on TEE were classified as “pocket”. Patients with positive blood cultures or lead vegetation were classified as a systemic infection named “systemic”. The patients were followed in the outpatient clinic at Rigshospitalet with clinical and echocardiographic control for up to 12 months and subsequently followed at the local cardiology ward.

Device removal was as follows: Complete device removal was performed in accordance with the Consensus document from the Heart Rhytm Society 2009 and the latest European guidelines.[Citation12,Citation13] The technique used for the lead extractions was introduction of a locking stylet and extraction with either non-powered or powered mechanical sheaths. The intracardiac part of the electrode and representative tissue samples from the pocket was cultured. As much tissue as possible was removed from the pocket capsule, thereafter the wound was sutured, in most cases without insertion of a drain. Pacemaker dependant patients had a temporary screw-in pacemaker lead inserted through either the internal jugular or subclavian vein to the right ventricle.

Antibiotic treatment was as follows: In case of Streptococcus aureus a beta-lactamase-resistant beta-lactam antibiotic in combination with fucidic acid. For Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcus (CoNS) two antibiotics with different antimicrobial action, to which the CoNS was sensitive was used. In most cases a single drug was used during the oral post re-insertion period. For streptococci, high dose benzylpenicillin was used in most cases. For Pseudomonas aeruginosa two antimicrobials with different antimicrobial action, to which the P. aeruginosa was susceptible was used. In most cases this consisted of a beta-lactam antibiotic (e.g. meropenem, ceftazidim or piperacillin), combined with an aminoglycoside, colistin or ciprofloxacin. In cases of enterobacteriaceae a similar approach was used.

Statistics

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous normally-distributed variables, as median (interquartile range) for continuous non-normally-distributed data, and as percentages for categorical data. Analysis of normality was performed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk test. Categorical data and proportions were compared using Chi2-test or Fisher’s exact test as required. Comparisons of continuous variables were analysed using unpaired t-test and the Mann–Whitney U-test as appropriate. Survival analysis and survival curves were obtained using the Kaplan–Meier method. p Values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were performed with SPSS 20.0 statistical package for Windows (SPSS 20.0, Chicago, IL).

Ethics

The study was entirely registry-based without direct participation of patients and informed consent from the patients was not required.

Results

During the period from April 2005 until March 2011 a total of 14,431 procedures (implantations, device exchanges, lead replacements) were carried out and 71 patients were treated for CIED infection.

Demographics of the patients are shown in . Type of device and the nature of the last procedure before the CIED infection are shown in . Comparison between the systemic or pocket presentation is shown. Indications for the device therapy were as follows: AV-block 25 (35%), sick sinus node syndrome 14 (20%), ischemic heart disease (primary prophylacsis) 10 (14%), heart failure 12 (17%), syncope 6 (8%) and other indications 4 (6%).

Table I. Demographics of all patients and divided into patients presenting with systemic or pocket presentation as defined in the text.

Table II. Type of device implanted and type of latest procedure before the current CIED infection divided into patients with systemic or pocket presentation as defined in the text.

Symptoms and bacteriology

At presentation the main symptoms were sign of local pocket infection in 48 patients (66%) and fever in 25 patients (35%). C-reactive protein (CRP) were elevated (>10 mg/L) in 40 patients (56%), with a median value of 14 (IQR 5–30) mg/L, leucocytosis (>10.9 × 109/L) was present in 11 patients (15%), median value of 7.40 (IQR 6–9.6) × 109/L. Patients in the systemic group as defined in the method section counted 32 (45%) and 39 (55%) in the pocket group.

In 49 cases (69%) the last procedure performed before CIED infection was a re-procedure (device exchange, device upgrade, or lead exchange) as compared to de novo implantations in 22 (31%) cases, but with no difference between the type of presentation.

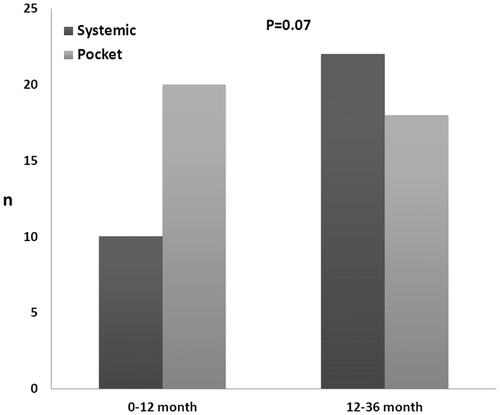

The time from last procedure varied from 12 to 9.464 days, with an accumulation of cases in the first three months (n = 15) accounting for 21% of the total number of cases observed in the total period. shows the time distribution from the last procedure to the presence of CIED infection divided into systemic or pocket presentation. The pocket presentation revealed to be more frequent in the “early” period (from 0 to 12 months) as compared to the “late” period (from 12 to 36 month) however not statistically significant, p = 0.07.

Figure 1. Time distribution from the last procedure to the presence of CIED infection divided into systemic or pocket presentation. The pocket presentation was more frequent in the “early” period (from 0 to 12 months) as compared to the “late” period (from 12 to 36 month) but only borderline statistically significant, p = 0.07.

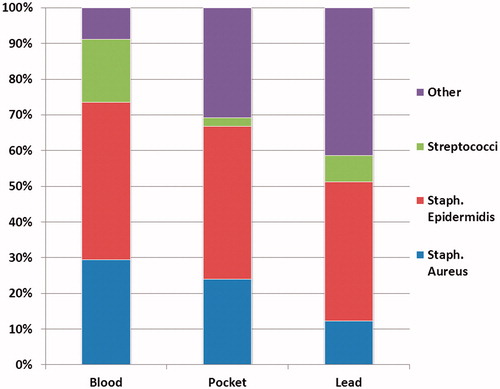

The results of the culture from blood, device leads and device pocket are shown in and . In 31 (43%) patient’s blood cultures were positive, with CoNS being the most predominant species followed by S. aureus, Streptococcus sp and others (one case of Escherichia coli, one case of Morganella morganii, one case of Probionebacteria acnes). Cultures from the pocket and device leads included a higher proportion of non-staphylococci and non-streptococci, like P. acnes and P. aeruginosa. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) was performed in all but three patients (96%), and lead vegetations were present in 31 (44%) of the patients examined. In 4 (6%) cases additional valvular vegetations were found, (two patient with aortic valve and two patients with tricuspid valve vegetations). These patients were treated according to ESC guidelines of infective endocarditis. When dividing patients into the defined groups of systemic or pocket presentation the systemic group (n = 32) had 88% (n = 28) positive blood cultures and 47% (n = 15) with a vegetation on the lead. The pocket group (n = 39) had positive cultures from the pocket in 77% (n = 30) which was significant and more frequent than in the systemic group where only 25% (n = 8) had positive pocket cultures (p < 0.01). Positive cultures from the leads where equally distributed among the pocket group 59% (n = 23) and systemic group 41% (n = 13), p = 0.12. When trying to distinguish the bacteriology from blood or pocket between the two groups only Streptococci sp were cultured more often in the systemic group as compared to the pocket group (22% vs. 2% systemic vs. pocket, p < 0.01). S. aureus and CoNS cultured from blood or pocket were equally distributed among the systemic or pocket group (S. aureus: 25% vs. 28%, systemic vs. pocket, p = 0.76; CoNS: 50% vs. 49%, systemic vs. pocket, p = 0.91).

Table III. Specification of “other” bacterias from .

Diagnosis

The three major diagnostic criteria for CIED infection: positive blood culture, signs of local pocket infection and lead-vegetation on echocardiography, and their combination, were analysed. Of note no patient had signs of all three criteria. Most patients had signs of local pocket infection either alone (53%) or in combination with positive blood culture (7%) or a positive TEE (6%). A positive blood culture alone was the criteria in 18% and in combination with TEE in 14%. TEE alone was only the reason for CIED removal in one case, but in this case a vegetation on the aortic valve was present and the patient had fever and elevated leukocytes and CRP.

Mortality and follow up

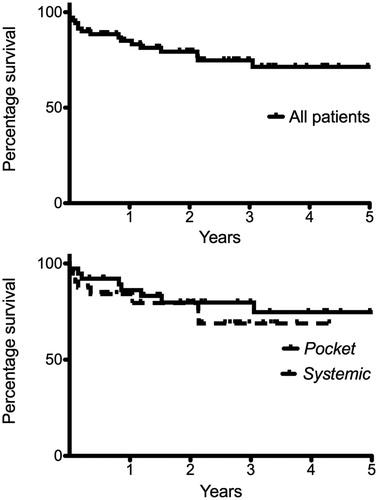

Three patients (4%) died within 30 days. Two patients died shortly after the CIED removal procedure due to bleeding complications, despite surgical intervention. One patient died of cardiac arrest due to severe heart failure (LVEF of 10%). Within 12 month a total of 10 patients (14%) died, among which four patients with heart failure (LVEF 15–35%) died due to cardiac arrest and nephropathy; one patient aged 81 years died due to pneumonia, one patient died of terminal nephropathy and one died from cancer. There was no difference in mortality when comparing the two defined sub-groups “pocket” vs. “systemic”, p = 0.48, see . In patients surviving 12 month the mean follow up time was 33 ± 22 months. During this follow-up time only two cases of re-infection were observed, one case was 13 month after the CIED infection and the other case 21 month after the CIED infection. Since both cases were due to S. aureus and patients had not been treated repeatedly with antibiotics, the cases were diagnosed as re-infections rather than relapse of the previous infection.

Discussion

In this detailed long-term follow-up of patients with CIED infections treated with complete device removal followed by antibiotic treatment of long duration we observed an overall low mortality (30 day mortality of 4% and 12 month mortality of 14%) without cases of relapsing infection. The clinical presentation as defined by the systemic or pocket group showed that the two groups were very similar in terms of co-morbidities, type of device and latest procedure and we found that the mortality was similar in both groups. The difficulties in differentiating a local pocket infection from a systemic infection supports the very similar way of treating all CIED infections with device removal and could suggest that even the length of antibiotic treatment should be similar in most cases. Previous studies have shown that sepsis is a major riskfactor for mortality [Citation14,Citation15] and in this cohort no deaths were attributed to sepsis which might explain why mortality was similar in the pocket and systemic group.

Mortality and re-infection are reported with varying results in the literature. Studies with CIED infections where the device is not removed results in unreasonable high mortality and infectious relapse. Athan et al. reported that one year mortality of 38% in patients with CIED infections where the device was not removed [Citation16] and Molina et al. reported that long hospital stays of more than 100 days and immediate mortality of 17% and complete failure of conservative strategy.[Citation17] Rundstrom et al. reported that one year mortality of 38% and relapse of infections also in 38% in patients with CIED infection when trying to treat conservatively.[Citation10] Until recently long term mortality was reported to be determined by co-morbidities rather than the CIED infection itself, but more recent and larger follow up studies have shown doubling of mortality in patients with CIED infections.[Citation3,Citation18]

When we compared our results with other studies where CIED infections are handled with device removal and concomitant antibiotic the results are varying. In-hospital mortality of 3.7%,[Citation19] 7%,[Citation20] 14%, [Citation8] 14.7% [Citation16] are reported however due to short term follow up [Citation8,Citation21] or missing data [Citation5,Citation10] fewer studies report later mortality but numbers of six month mortality of 25% [Citation20] and one year mortality of 23% [Citation16] are reported. By comparing the previous data with the current findings we found that both short and long term mortalities during a median follow up of 26 months was low. We believe that long term follow-up is important to capture slow evolving pocket infections with bacteria’s of low virulence, like P. acnes.

Overall, we observed a comparable distribution of age, sex and rate of primary S. aureus and CoNS to previous reports.[Citation5,Citation8,Citation16,Citation19,Citation20] Our findings, confirm previous studies, in which the majority of CIED infections (66%) occur following a re-procedure rather than a de novo procedure.[Citation5,Citation22]

The bacteriology only differed slightly, counting more streptococci in the systemic group than the pocket group. However, the pocket presentation tended to be more often in the group of CIED infections presenting within the first 12 months from last procedure.

Our present treatment regime, device removal combined with four weeks of antibiotics, re-implantation of a new device on the contra lateral side, and followed by another two weeks of antibiotics, predominantly oral administered, may be considered longer than necessary. In the most recent AHA statement, endorsed by the Heart Rhytm Society, CIED infections are recommended to be treated by device removal followed by two weeks of antibiotics in cases of non-S. aureus and followed by four weeks in cases of S. aureus.[Citation4] The timing for re-implantation (four weeks) was also far longer than current recommended and maybe could account for the low re-infection rates. Although our population may vary in comorbidity from the US population, we believe that the low short and long term mortality as well as the low occurrence of re-infection could be due to the long duration of antibiotic treatment. Long term antibiotic treatment also carries risk of complications, like central venous catheter related infections, diarrhea, allergic reactions and nephropathy. Nephropathy was reported as being present in 21% and other co-morbidities linked with nephropathy like diabetes (18%), hypertension (31%) and IHD (38%) were also frequent. In 30% of the patients who died within the first year with nephropathy, directly or indirectly as the cause of death, and it is possible that antibiotic treatment, especially aminoglycosides, can contribute to this development.[Citation23] However, the infection itself may also induce and cause progression of existing renal disease.[Citation24]

One very recent study reporting follow-up time of 25 month has used a regimen similar to ours and in accordance report one year mortality of 14%,[Citation18] supporting the safety of this regimen.

In conclusion, systemic and pocket infections can present very similar clinically and longterm follow up showed similar and low mortality when using a regimen of complete device removal combined with a total of six weeks antibiotic treatment. We suggest that future randomized studies should asses the optimal treatment regiments and due to low number of endpoints cluster randomized could be used.[Citation25]

Limitations

The study is a retrospective register based study with the possible errors in the collection of data. We report CIED infections by using the registers of CIED removals and possibly some cases of recent implanted devices could have been removed locally thereby underreporting the number of cases. Patient moving in and out of our region could disturb the count of procedures as compared to CIED infections recorded, but since there is no general tendency of moving to or from Zealand we believe that this will not affect our results. The cultures from the device leads might be contaminated during extraction trough an infected device pocket, thereby over reporting the amount of infected leads in a true pocket infection.

Declaration of interest

No authors have any financial disclosures.

References

- Voigt A, Shalaby A, Saba S. Rising rates of cardiac rhythm management device infections in the United States: 1996 through 2003. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:590–591.

- Greenspon AJ, Patel JD, Lau E, et al. Trends in permanent pacemaker implantation in the United States from 1993 to 2009: Increasing complexity of patients and procedures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1540–1545.

- Rizwan Sohail M, Henrikson CA, Jo Braid-Forbes M, et al Increased long-term mortality in patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2015;38:231–239.

- Baddour LM, Epstein AE, Erickson CC, et al. Update on cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections and their management: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:458–477.

- Klug D, Balde M, Pavin D, et al. Risk factors related to infections of implanted pacemakers and cardioverter-defibrillators: Results of a large prospective study. Circulation. 2007;116:1349–1355.

- Durack DT, Lukes AS, Bright DK. New criteria for diagnosis of infective endocarditis: utilization of specific echocardiographic findings. Duke Endocarditis Service. Am J Med. 1994;96:200–209.

- Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:633–638.

- Sohail MR, Uslan DZ, Khan AH, et al. Infective endocarditis complicating permanent pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator infection. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:46–53.

- Habib G, Hoen B, Tornos P, et al. Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009): The Task Force on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) and the International Society of Chemotherapy (ISC) for Infection and Cancer. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2369–2413.

- Rundstrom H, Kennergren C, Andersson R, et al. Pacemaker endocarditis during 18 years in Goteborg. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:674–679.

- Nielsen JC, Gerdes JC, Varma N. Infected cardiac-implantable electronic devices: Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2484–2490.

- Bongiorni MG, Marinskis G, Lip GY, et al. How European centres diagnose, treat, and prevent CIED infections: Results of an European Heart Rhythm Association survey. Europace. 2012;14:1666–669.

- Wilkoff BL, Love CJ, Byrd CL, et al. Transvenous lead extraction: Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus on facilities, training, indications, and patient management: this document was endorsed by the American Heart Association (AHA). Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1085–1104.

- Baman TS, Gupta SK, Valle JA, Yamada E. Risk factors for mortality in patients with cardiac device-related infection. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:129–34.

- Margey R, McCann H, Blake G, et al. Contemporary management of and outcomes from cardiac device related infections. Europace. 2010;12:64–70.

- Athan E, Chu VH, Tattevin P, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of infective endocarditis involving implantable cardiac devices. JAMA. 2012;307:1727–1735.

- Molina JE. Undertreatment and overtreatment of patients with infected antiarrhythmic implantable devices. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:504–9.

- Deharo JC, Quatre A, Mancini J, et al. Long-term outcomes following infection of cardiac implantable electronic devices: A prospective matched cohort study. Heart. 2012;98:724–731.

- Sohail MR, Uslan DZ, Khan AH, et al. Management and outcome of permanent pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator infections. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1851–1859.

- Greenspon AJ, Prutkin JM, Sohail MR, et al. Timing of the most recent device procedure influences the clinical outcome of lead-associated endocarditis results of the MEDIC (Multicenter Electrophysiologic Device Infection Cohort). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:681–687.

- Sohail MR. Management of infected pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Intern Med J. 2007;37:509–510.

- Johansen JB, Jorgensen OD, Moller M, et al Infection after pacemaker implantation: Infection rates and risk factors associated with infection in a population-based cohort study of 46299 consecutive patients. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:991–998.

- Mingeot-Leclercq MP, Tulkens PM. Aminoglycosides: nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1003–1012.

- Majumdar A, Chowdhary S, Ferreira MA, Hammond LA, et al. Renal pathological findings in infective endocarditis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:1782–1787.

- Brown AW, Li P, Bohan Brown MM, et al. Best (but often forgotten) practices: Designing, analyzing, and reporting cluster randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102:241–248.