Abstract

Introduction Participation in clinical trials by patients with cardiovascular disease is paramount to the development of new treatments. Capturing and keeping patients in the trials until the end is very important and trials are often of long duration and include patients in a clinically stable condition, with few symptoms and a low risk of recurrent disease. We investigated what motivates patients to participate in long-term cardiovascular trials. Increased knowledge may enhance inclusion and retention and minimize lost to follow-up or withdrawal of consent. Materials and methods A questionnaire with 11 statements to elucidate the reasons for participation and retention in long-term clinical trials was used and replies from 135 participants in trials, 78% men, mean age was 68 years. Results The two most important reasons for participation were: “I am able to see the same doctor and nurse at the visits”, indicated by 89 patients (66%), followed by “I want to promote science”, which was indicated by 74 patients (55%). The least important reason was “The visits are free of cost”. Conclusion Patients who participate in cardiovascular clinical trials do so because it may provide access to more continuous care but equally important are altruistic motives including a wish to promote science.

Introduction

Participation in clinical trials by patients with cardiovascular disease is paramount to the development of new pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments. Participation may be affected by the disease treated, randomization, the use of placebo, as well as financial and structural aspects of the health-care system.[Citation1] Access to the novel, investigative treatments may also be an important factor but altruistic motives, i.e., the advancement of science, are sometimes cited in trials of novel cancer treatments.[Citation1–3] Patient-related factors such as age, gender and severity of disease may also affect willingness to participate in trials,[Citation4] and trials may be seen by the participants as adding physical and emotional value.[Citation5]

Continuity of care has been shown to be a factor significantly associated with adherence to medication.[Citation6,Citation7] Adherence to medication is vital in all kinds of clinical trials. Retention, i.e., keeping the patient in the trial and on the investigative treatment, is paramount in large-scale, long-term clinical trials. Substantial drop-out and lost to follow-up may severely limit the trials statistical power both in terms of determining positive effects but also in terms of detecting less frequent, potentially serious adverse effects. A high frequency of lost to follow-up and withdrawal of consent may render the trial less valuable from a clinical, scientific as well as commercial perspective.[Citation8,Citation9]

Clinical cardiovascular trials are often of long duration and include patients who are in a clinically stable condition with few symptoms and, in absolute terms, at relatively low risk of recurrent disease.[Citation10–12]

We were interested in the reasons why patients choose to participate in clinical cardiovascular long-term trials and the factors that participants found most important to remain in the study until the end of the trial. Increased knowledge of what motivates patients to participate may enhance inclusion and retention and minimize lost to follow-up or withdrawal of consent, thus providing better care and more valid scientific results.

Study objectives

To explore the importance of the following motivational areas: better and more consistent care, altruism, financial reasons, convenience and access to novel medications and procedures.

Methods

In our academic, government, hospital-based research unit, we have long-term experience with clinical trials, mostly in the cardiac or cardiovascular field. We were unable to identify any previous published suitable questionnaire. After several discussions within our team as well as with patients, we formulated a pilot questionnaire with 11 statements to elucidate the reasons for participation and retention in long-term clinical trials.

We identified patients who participated in at least one of eight different cardiovascular trials that were either ongoing at our institution or that had been completed less than 2 years earlier, i.e., before the end of 2011. The eight trials were secondary preventive trials of antiplatelet, lipid-lowering, antidiabetic, plaque-stabilizing or anti-inflammatory pharmacological treatment after myocardial infarction and/or stroke. In addition, patients with a persistent foramen ovale post cryptogenic stroke participating in a trial randomizing to device closure or antiplatelet treatment were included.

Stage 1. We constructed a preliminary version and mailed it to 15 patients as a pilot study. All patients had previously or were currently participating in one of our clinical cardiovascular long-term trials. After receiving the answers, we changed the questionnaire to improve clarity, removed obviously redundant material or questions or items that were less easy to understand for the patients. No other formal validation was performed.

Stage 2. The improved set of questions was then mailed to all current or previous (within the last 2 years) participants in clinical trials at our site. The 11 statements patients were asked to consider were:

Why do you participate in clinical research?

I want to promote science.

The visits are free of cost.

I am able to see the same doctor and nurse at the visits.

I can call and get medical advice almost whenever I want.

I have been helped by others and I would now like to give back.

I get helpful advice about health and lifestyle.

It is easier to get new medical prescriptions.

I hope to try a new medication that can help me feel better.

I get an extra check-up beyond my ordinary visits.

It provides security that the staff knows me.

I wished for better follow-up after my cardiovascular event than ordinary primary care can provide.

The pilot questionnaire was mailed to patients in July 2013. The final questionnaire was mailed to patients from August to October 2013. The answers were anonymous and no reminders were sent. All questionnaires were mailed to the patients and either mailed back or anonymously dropped in a dedicated mailbox located in the research unit. The patients scored each statement on a 5-grade scale from “highly accurate” to “not accurate at all”. Patients were also asked to identify the three most important statements. We also asked for information on age, gender, for how long they had been participating in a trial and if they had participated in more than one trial. Information on the number of cardiac procedures, hospitalizations, whether they had been diagnosed with heart failure or diabetes, and whether they had had an acute myocardial infarction was provided by the patients in the study form. Statistics were descriptive only.

Results

The revised questionnaire was mailed to 154 patients who had either participated within the last 2 years or were now participating in a cardiovascular clinical study. We received replies from 135 participants (88%), 78% of participants were men and the mean age of participants was 68 years. The total duration of trial participation (including also other, previous trials) as reported by the patients was 4.3 years (range 2 months–15 years) and the majority of patients had participated in only one trial. Of the participants, 92% had a previous myocardial infarction and 8% a previous stroke as the index event for inclusion in one of our studies ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the 135 participants.

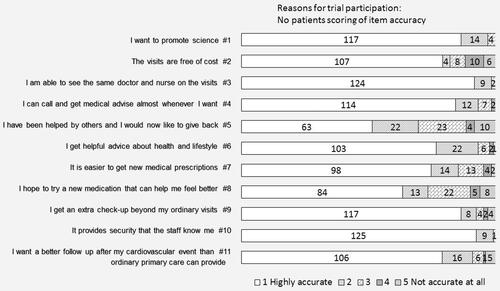

Each item was scored by the patient according to how accurately a given statement described the patient’s own opinion. The two statements considered to be the most accurate by the patients were items 3 and 10, “I am able to see the same doctor and nurse” and “It provides security that the staff knows me”. The two least accurate statements were 5 and 8, “I have been helped by others and I would now like to give back” and “I hope to try a new medication that can help me feel better” ().

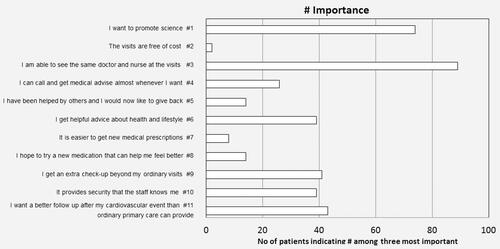

The patients were also asked to rank each statement as to how important it was. The three most important reasons for participation were: “I am able to see the same doctor and nurse at the visits”, indicated by 89 patients (66%), followed by “I want to promote science”, indicated by 74 patients (55%) and 43 patients (32%) indicated that “I wished for better follow-up after my cardiovascular event than ordinary primary care can provide”. The least important reason was “The visits are free of cost”, which was indicated to be important by only two patients ().

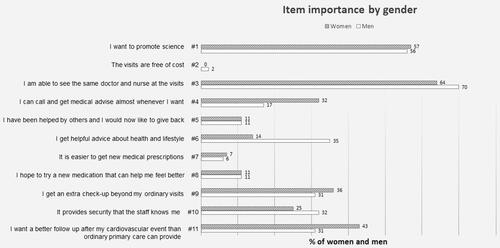

The results were equal for men and women for all questions with two exceptions. Women indicated to a greater extent that telephone advice was important (item 4) than men (32% versus 17%). On other hand, more men stated that getting helpful advice on health and lifestyle, item 6, was very important as compared with women (35% of men versus 14% of women; ).

Discussion

Patients who participate in cardiovascular clinical trials do so because it may provide access to better and more continuous care but equally important are altruistic motives, including a wish to promote science. While there are a number of reports on motives for patients to participate in clinical trials, these come mainly from other fields of medicine, i.e., cancer treatment, rheumatology and surgical trials.[Citation1–7] We found that patients presented two major and important reasons to participate in long-term trials. The first was an altruistic motive, to promote science, which is line with previous findings.[Citation1–3,Citation13,Citation14]

The second important reason stems from self-interest, i.e., continuity of care. This finding may reflect circumstances that are related to the specific setting of primary health care in our particular area, i.e., difficulties with staffing and problems with continuity. The responses, nevertheless, point to one of the potential advantages for the patients, i.e., stable, predictable care provided by a limited number of providers who are well known to the patient. This also promotes what is scientifically sound and important: to limit lost to follow-up and limit the number of patients who drop out of trials due to the withdrawal of consent.[Citation8,Citation9] In this respect, patient preferences and scientific and regulatory interests coincide.

Our results may be valid also for other clinical trials outside of the cardiovascular field. In a study of trial participants in a long-term rheumatology trial,[Citation13] three-quarters of patients indicated that altruistic motives such as “contributing to scientific research” were very important as motivators. Interestingly, they also found that good relationships with staff and tight disease monitoring were important reasons for continuing participation in a long-term trial.

Economic issues were less important to our patients. Study visits were all free, and in the Swedish health-care system the patient fee for outpatient visits outside study participation is subsidized and low-cost (20–30 Euros).

Cardiovascular long-term trials are secondary prevention trials in which patients are, in general, in a stable condition and mostly asymptomatic, and in which the novel treatment studied can at best be expected to diminish the risk of future morbidity and mortality. This is in contrast to trials of patients with, for example, rheumatologic disorders or cancer. However, willingness to help others has also been found to be an important reason in other trials, especially if associated with other perceived benefits, which is known as conditional altruism.[Citation14]

The ability to try novel medications that would improve the patient’s condition was not ranked highly, in contrast to what has been previously reported in trials of cancer medications.[Citation2–4] Our previous and ongoing cardiovascular trials were either phase 3 or late phase 2b trials that frequently used pharmaceutical therapies that are even available in the market. Thus, we are targeting patients who already have access to various risk-modifying treatments for which the overall, long-term cardiovascular safety and efficacy has not yet been established, for example, intensive lipid-lowering versus standard lipid-lowering treatment after acute coronary syndromes.[Citation12]

We also found a gender difference, in that women ranked the ability to contact the study nurses over the phone to get advice more highly than men, whereas men valued the possibility of receiving repeated lifestyle advice and counseling and support more than women.

A drop-out rate of 2–5% per year is often seen in long-term cardiovascular trials and for very long trials such a drop-out rate will result in substantially lower power to detect scientifically valid endpoints. This is often overcome by increasing the number of patients and the duration of the study, adding further cost and postponing the time that important findings are presented, potentially delaying important improvements in treatment.[Citation7,Citation10,Citation11] Expected and unexpected adverse events are important and valid reasons for stopping study treatment and may sometimes erroneously lead to the patient dropping out of the trial. It is therefore important to clearly inform patients at the time of inclusion in a long-term trial of the necessity of continuing visits within the trial regardless of whether study treatment is discontinued.

Our data are novel in that they represent the motivation of patients who are asymptomatic and in a stable condition and for whom the potential benefit of participation is mostly to avoid future morbidity and mortality.

Limitations

One limitation was that the patients only had the opportunity to answer the statements that we had chosen. We questioned patients that had previously participated in or who were currently engaged in a clinical trial and that can be assumed to bias in favor of trial participation. Our setting is an academic unit in a government hospital and in a specific health-care system. Another limitation was that the patients only had to choose the overall three most important statements without ranking them. Our questionnaire did not contain any space for free comments. We included only patients involved in trials of secondary prevention after cardiovascular events.

Conclusion

Patients who participate in cardiovascular clinical trials do so because they want to promote science but also because it may give them access to better care. Continuity of care, the opportunity to see the same staff and to be recognized was highly ranked by patients, in addition to a willingness to promote science. Purely egoistic and economic reasons were not important. This should be considered when recruiting patients into long-term cardiovascular trials.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Georg Lappas for statistical assistance.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Constantinou M, Jhanji V, Chiang PP, et al. Determinants of informed consent in a cataract surgery clinical trial: why patients participate. Can J Ophthalmol. 2012;47:118–123.

- Shah A, Efstathiou JA, Paly JJ, et al. Prospective preference assessment of patients’ willingness to participate in a randomized controlled trial of intensity-modulated radiotherapy versus proton therapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:e13–e19.

- Scheck McAlearney A, Song PH, Reiter KL. Why providers participate in clinical trials: considering the National Cancer Institute’s Community Clinical Oncology Program. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:1143–1149.

- Kasner SE, Del Giudice A, Rosenberg S, et al. Who will participate in acute stroke trials? Neurology. 2009;72:1682–1688.

- Jenkins V, Farewell D, Batt L, et al. The attitudes of 1066 patients with cancer towards participation in randomised clinical trials. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1801–1807.

- Verheggen FW, Nieman F, Jonkers R. Determinants of patient participation in clinical studies requiring informed consent: why patients enter a clinical trial. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;35:111–125.

- Tamblyn R, Eguale T, Huang A, et al. The incidence and determinants of primary nonadherence with prescribed medication in primary care: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:441–450.

- Mega JL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, et al. Rivaroxaban in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:9–19.

- http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/764433 Miller R: Missing Data Lead FDA Panel to Vote Against Rivaroxaban for ACS.

- CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). CAPRIE Steering Committee. Lancet. 1996;348:1329–1339.

- Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2195–2207.

- Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2387–2397.

- Markusse IM, Dirven L, Han KH, et al. Continued participation in a ten-year tight control treat-to-target study in rheumatoid arthritis: why keep patients doing their best? Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67:739–745.

- McCann SK, Campbell MK, Entwistle VA. Reasons for participating in randomised controlled trials: conditional altruism and considerations for self. Trials. 2010;11:31.