Readers will know that Bob Edwards died recently. In tribute to his life and career, we reproduce two documents: the first is from a letter written by Mark Hamilton, former BFS Chair, in support of the nomination of Bob for a Knighthood for “services to human reproductive biology”, subsequently awarded in 2011; the second is an address I gave on the occasion of the conferment to Bob of an Honorary Degree of Doctor of the University of York on 9 July 1987.

Bob Edwards has had a long association with the BFS since its foundation by his clinical collaborator, Patrick Steptoe. He was the second Honorary President of the Society holding office between 1988 and 1992.

Of course it is well known that in 1978 Edwards and Steptoe were the first to achieve the birth of a child after in vitro fertilisation. This was an event in the history of medicine which at a stroke changed our perspectives not only on the management of infertility, until then commonly based on intuition rather than good science, but also raised profound questions for society which challenge us even today. This translation of basic science, in very real terms from the bench to the bedside, led by Edwards, was a milestone in the history of mankind and rendered IVF as absolutely integral to the modern management of the infertile.

Beyond the enormous impact that IVF has made to clinical practice, science in reproductive medicine using IVF associated techniques has continued to flourish both clinically and in the laboratory. Prof. Edwards had a significant part to play in this, not least in his energy and drive in founding the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and in his role as Founding Editor of Human Reproduction, which has now evolved into three separate high impact publications. Edwards’ research provided the platform on which the science of stem cell and regenerative medicine was built, and with it the promise of astonishing possibilities for the relief of chronic debilitating medical conditions in the years to come. His research also played a key part in the development of pre-implantation genetic diagnosis.

Prof. Edwards has been acclaimed throughout the world for his pioneering work and has received many awards from universities, academic institutions and learned societies. Among his greatest scientific accolades have been the Lasker Award, the American version of the Nobel Prize in 2001, and of course the Nobel Prize in Physiology in 2010. He is an Honorary Member of the British Fertility Society, our highest honour, and many of our members have had personal experience of his inspirational enthusiasm for our subject and his ability to generate excitement in the chase for knowledge and truth. Prof. Edwards was honoured to give the first Patrick Steptoe Memorial Lecture at our annual meeting in 1991, and speakers since then, all leaders in our field from around the world, have referred with gratitude to his contribution to their professional lives.

MARK HAMILTON

Consultant Gynaecologist

Aberdeen Maternity Hospital

I first met Bob Edwards on October 22nd 1984. I was conducting a tutorial at the time when he appeared in my laboratory carrying a large box containing samples of medium in which some embryos had been incubated. He had driven the 160 miles from Cambridge to York to bring these samples for us to analyse. Over the next few months he made a further seven journeys, a total of 2,500 miles, usually arriving late on a Saturday night. He used to emerge heavily wrapped in layers of clothing because he had set the air-conditioning to make the inside of his car like a refrigerator, so as to keep the samples fresh.

I well remember meeting him half way one Sunday morning at the northern end of the Doncaster by-pass. His Jaguar had carried the samples smoothly until in the excitement of spotting me, he hit a ramp and sent them flying. His utterance would ill-become an occasion such as this.

These stories tell us a good deal about Bob Edwards; his almost legendary drive and enthusiasm; his passionate concern for embryos; and his refusal to let minor obstacles such as the distance between Cambridge and York interfere with the pursuit of research.

Bob is a Yorkshireman. He remains dogged, gritty and outspoken, but warm and generous. After wartime service in the army, he went to the University of Bangor in North Wales to study agriculture. For him it was a mistake. He was less interested in the seeds of plants than in those of animals, and emerged with an ordinary degree without honours. As he was later to write: ‘I was disconsolate. It was a disaster – I was 26 and skint.’

By now, he knew that he wanted to study the early stages of animal life and persuaded Professor C.H. Waddington of the Institute of Animal Genetics at Edinburgh University to accept him as a student at a salary of £240 a year. He never looked back. It is perhaps worth pointing out that this sort of start to a scientific career would be quite impossible in these days of ‘performance criteria’.

Much of his work in Edinburgh was on the processes which occur in the egg prior to ovulation, work in which Ruth, his wife, acted as collaborator. His work also indicated the precise time to collect ripening eggs from the ovary. As well as having clinical applications, this has led to benefits in the breeding of domestic animals and threatened species. After Edinburgh, he moved to the National Institute for Medical Research at Mill Hill in London, and in 1963 to the Physiological Laboratory at Cambridge University.

Subsequent events are well known: his meeting with Patrick Steptoe, one of the most fruitful partnerships between a clinician and a scientist this century; his endless commuting between Cambridge and Oldham; and his battles with the scientific and medical establishment prior to the birth of the world's first ‘test-tube baby’ in 1978.

It is impossible on an occasion such as this even to summarise the key events involved, but what emerges is a supremely human tale – of great determination to study human embryos and allow infertile couples to bear their own children.

It is now belatedly recognized that in his concern for the impact of his work on society he was well ahead of his time. As early as 1969, i.e., 15 years prior to the Warnock Report, he began making calls for investigations, committees and legislation to clarify the status of embryos, patients and doctors – without any response. I quote from a paper he co-authored in 1971:

‘We believe that it is important at this stage to elaborate the emerging issues in order to give time for defining and evolving social attitudes on which to base rules of conduct for scientists in society . . . to offer comments and suggestions on ways of helping society, science and law to live more safely, harmoniously and with greater confidence in keeping pace with advances in human embryology and other disciplines.’

And again, in 1975:

‘A significant number . . . of new moral and ethical issues . . . also arise from medical and technical advances in specific areas of research, which challenges established ideas or open new possibilities of choice. . . . While the excessive publicity lavished on these advances is to be deplored, the attention they attract should be welcomed by those concerned in discussing and establishing ethical and social standards or social awareness, for the resulting discussion often concern people in many different professions and with widely diverging views.’

Despite this, the government did not set up its own enquiry until 1982. Indeed the whole saga has been called an exquisite paradigm of the incapacity of contemporary British politics to anticipate rather than to react.

As a scientist, I think Bob will be remembered, along with Peter Mitchell, a fellow honorary Doctor of this University, as one of the last biologists to have opened up a major new area of his subject virtually single-handed. In recognition of his scientific achievements, he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1984. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists made him an Honorary Fellow in 1985, a rare award for a non-clinician. In 1985, he was instrumental in founding the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology and its journal Human Reproduction. As a member of the Society and the editorial board of the journal, I have watched him chair many meetings. He can do it brilliantly, using generosity, good humour and an impeccable sense of timing to get his own way: skills no doubt acquired from being a member of Cambridge City Council.

Bob Edwards is an inspirational figure, a distinguished scientists and teacher for whom a mundane look down a microscope becomes a eulogy about nature. Many of his two dozen or so graduate students are leaders in their fields. He has, incidently, discovered the secret of sex preselection, in that he and his wife produced five daughters, the last two of whom were twins.

It is unfortunate that our Chancellor, Lord Swann, is unable to be with us to confer this award, for, as some of you may be aware, he was himself a distinguished embryologist and an authority on the way in which cells divide. In 1981, when the University had just received the first of the recent UGC letters (which concerned cuts in university funding - Editor), I well recall his remarks at the graduation ceremony. He said we should not lose our nerve. Today, we honour someone who never lost his nerve.

Pro-Chancellor, I have the honour to present to you Professor Robert Edwards for the degree of Doctor of the University honoris causa.

Post script May 2013

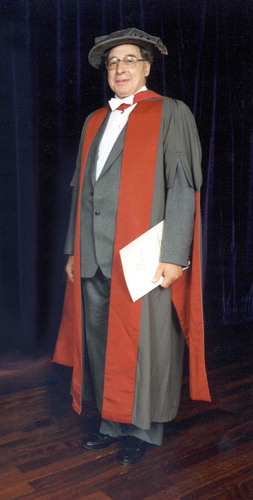

This occasion had its funny side. Bob arrived without having read the instructions on what he should wear for the presentation; a morning suit, soft white shirt and white bow tie. So with only about an hour to go before the ceremony, I drove him as quickly as I dared to the York branch of Moss Bros (for non-UK readers, a high street chain of clothing shops, well-known for their hire business) and Bob was suitably kitted out, as the illustration shows!

Looking back, I think the York Honorary Degree was only the second he received; the first was from the University of Hull, also in Yorkshire, when one might have expected him to have been honoured much more widely. In fact, I always felt Bob was refreshingly anti-establishment and it was a long time before he was accepted by those in the UK we term ‘the great and the good’.

However, 5 million babies could not be wrong and we shall miss him greatly.

It is especially fitting that Human Fertility is able to begin this issue with a wonderful article entitled Barrenness Vanquished: the legacy of Leslie Brown, by Eli Adashi and Howard Jones Jr., who with his wife, Georgeanna, pioneered IVF in the USA.