Abstract

Background. Anemia is a recognized prognostic factor in many chronic illnesses, but there is limited information about its impact on outcomes in patients hospitalized for acute COPD exacerbation (AECOPD). Aim. To investigate whether anemia exerts an effect on mortality in patients admitted for AECOPD after one year of follow-up. Methods. From November 2007 to November 2009 we recruited 117 patients who required hospitalization due to an AECOPD. Clinical, functional and laboratory parameters on admission were prospectively assessed. Patients were followed up during one year. Mortality and days-to-death were collected. Results. Mean age 72 (SD ± 9); FEV1 37.4 (SD ± 12); mortality after 1 year was 22.2%. Mean survival: 339 days. Comparing patients who died to those who survived we found significant differences (p < 0,000) in hemoglobin (Hb) (12.4 vs 13.8 mg/dl) and hematocrit (Ht) (38 vs 41%). Anemia (Hb < 13 g.dl-1) prevalence was 33%. Those who died had experienced 3.5 exacerbations in previous year vs 1.5 exacerbations in the case of the survivors (p = 0.000). Lung function and nutritional status were similar, except for percentage of muscle mass (%) (35 vs 39%; p = 0.015) and albumin (33 vs 37mg/dl; p = 0.039). These variables were included in a Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Model; anemia and previous exacerbations resulted as independent factors for mortality. Mortality risk for patients with anemia was 5.9(CI: 1.9–19); for patients with > 1 exacerbation in the previous year was 5.9(CI: 1.3–26.5). Conclusion. Anemia and previous exacerbations were independent predictors of mortality after one year in patients hospitalized for AECOPD.

| Abbreviations | ||

| AECOPD: acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BMI: body mass index; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP: C-reactive protein; FVC: forced vital capacity; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FFMI: Free fat mass index; GOLD: Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; Hb: Hemoglobin; Ht: Hematocrit; ICU: intensive care unit; LTOT: long-term oxygen therapy; MRC: Medical Research Council; pCO2: partial pressure of carbon dioxide; pO2: partial pressure of oxygen; SGRQ: St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire; 6MWD: 6-minute walk distance | = | |

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major public health problem associated with increasing worldwide morbidity and mortality (Citation1). The prognosis of this disease has been widely investigated and is associated to multiple factors that vary with respect to studied population: stable COPD, patients after hospitalization for AECOPD and patients after admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) for AECOPD.

Identification of the mortality-related variables after hospitalization for AECOPD is a clinically relevant issue, since exacerbations have an independent adverse impact on disease outcomes (Citation2–5). Moreover, recent studies suggest that patients with repeated exacerbations could constitute a particular phenotype (Citation6). Functional status, age, hypercapnia, body mass index (BMI), serum albumin, cor pulmonale and co-morbidity are some of the prognostic determinants most commonly reported in AECOPD patients (Citation7–9).

Anemia as an associated co-morbidity is a recognized independent marker of mortality in several chronic diseases (Citation10–12). Available studies in the literature have reported that anemia in patients with COPD may be more frequent than expected (Citation13–17); additionally, level of hemoglobin (Hb) in stable COPD patients is strongly and independently associated with increased functional dyspnea, decreased exercise capacity as well as poor quality of life (Citation13–19, Citation20). Low hematocrit (Ht) also has proven to be a predictor of survival in COPD patients with long-term oxygen therapy (Citation13,Citation21) (LTOT), patients with severe emphysema (Citation22) and among COPD patients with acute respiratory failure requiring invasive mechanical ventilation (Citation23). However, little is known about the prevalence and impact of anemia on mortality and other outcomes in patients with AECOPD.

We hypothesized that anemia is a frequent clinical finding in AECOPD and could influence the final prognosis of disease in this subgroup of patients. Accordingly, we conducted a one year single-institution follow-up study in a cohort of patients with AECOPD. Hb and other variables that might be potential determinants of mortality were also analyzed.

Methods

Patients admitted for AECOPD to the pulmonology ward of the University Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol were consecutively included between November 2007 and November 2009. The hospital serves a population of about 250,000 people for this pathology, thus ensuring that the study sample was a representative selection of pulmonary patients in the region. The diagnosis of COPD was based on current or past smoking history (≥10 pack-years) clinical evaluation, and pulmonary function testing showing airflow obstruction according to GOLD criteria (Citation1).

Patients requiring immediate ICU monitoring and/or noninvasive or invasive ventilation were not included. Those with established hematologic disorders, cancer diagnosis, severe sepsis or advanced chronic renal failure were also excluded. An exacerbation was defined by the presence of an increase in at least two of the following three symptoms: dyspnea; cough; and sputum purulence severe enough to warrant hospital admission (Citation24). During hospital admission, exacerbations were treated according to GOLD guidelines (Citation1). The ethics committee of our hospital approved the study (number CEIC-PUB-2007-001) and patients provided informed written consent.

The following variables were assessed at baseline: age, sex, smoking habit, spirometric values, number of hospitalizations and visits to the emergency department in the previous year and number of days in hospital. Clinical examination, as well as treatment regimens, including long term oxygen therapy (LTOT), was also recorded. Baseline functional dyspnea (in stable condition after admission) was measured using the Medical Research Council (MRC) (Citation25). Health-related quality of life was investigated with the validated Spanish translation of St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) (Citation26) and co-morbidity was measured for all patients according to Charlson index (Citation27).

On hospital admission the following data were collected using standardized procedures: Hemogram, blood gas levels, lipid profile, C-reactive protein (CRP), albumin, prealbumin, total protein, fibrinogen, and electrocardiogram. BMI was measured in kilograms per square meter. Body composition was assessed by bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), with a commercially available body analyzer (BIA RJL-101, Akern S.r.l, Florence, Italy) according to current recommendations (Citation28). Free mass index (FFMI) was calculated as FFM/height squared.

Patients were categorized into two groups according to Hb thresholds (anemic and non-anemic). The values considered by the World Health Organization (WHO) as reference for anemia are: for women Hb < 12 g.dL-1, for men Hb < 13 g.dL-1 (Citation29). In our study, a threshold of 13 g.dL-1 was chosen, as the vast majority of patients were male (93%) and the anemia definition in post-menopausal females remains controversial (Citation17,Citation30). The primary outcome measure was survival at one year. Mortality and cause of death were determined through family contact followed by a review of medical records and death certificates.

Statistical analyses

Results are shown as mean ± SD values for quantitative variables and as relative frequency and percentage for qualitative variables. Comparisons between quantitative variables were performed with the Mann–Whitney U-test. Comparisons between categorical variables were performed with the χ2 test. Comparisons of individual predictor of mortality of variables were performed using Cox regression analysis. To perform this analysis the variables were dichotomized by the median, except for anemia. To determine independent predictors of mortality, all predictor variables were included in a Cox proportional hazards model.

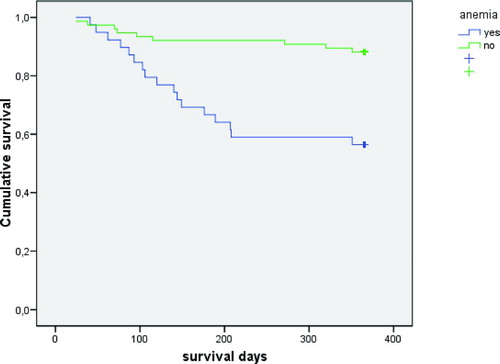

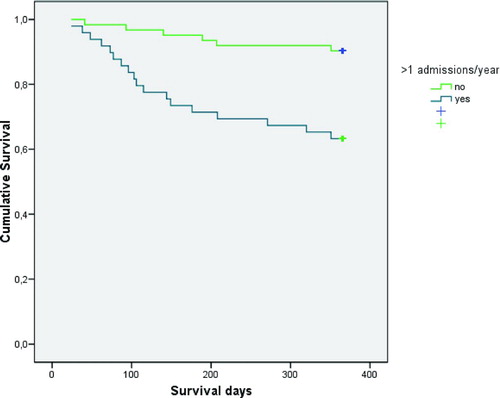

Survival plots for the influence of anemia and having had more than one exacerbation in the previous year were drawn and analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Values of p ≤ 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Of 117 patients in the dataset 26 (22.2%) died during the following year. The average number of survival days was 339. Anemia was present in 39 of 117 patients (33%), while no patient had polycythemia (Ht value > 55%). Demographic data and parameters related to nutrition, inflammatory markers, hemoglobin and hematocrit are listed in Tables and .

Table 1. Characteristics of 117 patients with AECOPD

Table 2. Data relative to nutrition, hemoglobin, hematocrit and inflammatory parameters of 117 patients with AECOPD

It was observed that patients who died at one year had higher dyspnea according to the MRC scale, and worse scores on the SGRQ activity (both at the limit of statistical significance) and, significantly, a greater number of Hospital, Emergency Care admissions as well as rounds of steroids in the previous year. Variables such as FEV1, age and Charlson co-morbidity index were similar in survivors and non survivors ().

Table 3. General characteristics comparing survivors and non-survivors

Non-survivors had a significantly lower hemoglobin, hematocrit, percentage of muscle mass and albumin (). It was confirmed that 65.4% of patients who died had anemia in contrast with 24.7% of COPD who survived (p < 0.000, χ2 test). In addition it was observed that up to 43.6% of patients with anemia died during the following year in contrast to 11.8% of COPD patients without anemia (p < 0.000, χ2 test).

Table 4. Data relative to nutrition, inflammatory and anemia parameters, comparing survivors and non-survivors

Subsequently, variables were dichotomized by the median except hemoglobin.

An analysis was made by univariate Cox regression model to identify whether each of these variables accounted for a greater RR for mortality. Thus, there were four variables that predicted higher mortality: a serum albumin < 36 mg/dl, a score in the SGRQ activity subscale of >79.5, registering more than one hospital admission in the previous year and having anemia ().

Table 5. Univariate Cox proportional hazards model for factors associated with mortality

A survival plot of Kaplan-Meier was made for all these variables. We observed that patients with anemia had a mean survival of 265 ± 19.9 days, as opposed to non anemic patients who had 340 ± 9.3days (log rank test: p < 0.000) (). In addition, patients with albumin < 36 mg/dl had a lower survival (292 vs 335 days; log rank test: p = 0.012), similar to those that scored more than 79.5 in subscale of activity of SGRQ (297 vs 334 days; log-rank test: p = 0.040) and patients with more than one hospital admission in the previous year (281 vs 347 days; log rank test: p < 0.000) ().

Figure 2. Survival plot regarding influence of admissions in previous year using the Kaplan-Meier test (log rank test: p < 0.000).

Finally these variables were included in a multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Model, and two variables remained independent predictors of mortality; anemia and having had more than one exacerbation in the previous year.

Patients with anemia had a RR to death of 5.9 (IC 95% 1.9–18.9; p = 0.003), patients with more than one hospital admission in previous year had a RR to death of 5.9 (IC 95% 1.3–26.5; p = 0.021), (). Therefore, patients with anemia and those that required more than one hospitalization over the previous year had a RR to die in the next year 6 times higher in both cases independently of albumin, quality of life, dyspnea, and percentage of muscle mass. Eleven of 26 patients (42.3%) died due to a respiratory insufficiency in the context of AECOPD. The other causes of mortality are included in .

Table 6. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards model for factors associated with mortality

Table 7. Causes of death

Discussion

The results of the present study show that anemia is a prevalent co-morbidity in patients with AECOPD (33%) and together with previous exacerbations constitutes the main risk factors for mortality in this cohort after one year of follow-up. The mortality rate found (22.2%) is consistent with previous reports (Citation7–9) although the in-hospital mortality rate in our population was lower. This discrepancy may be explained by the fact that we did not include patients requiring either admission to ICU or non-invasive mechanical ventilation. The reason for this exclusion is based on that both–ICU admission and need for ventilatory support–have been reported as the most important predictors of COPD in-hospital mortality (Citation31,32), so it could have induced the identification of factors that might not be applicable to exacerbations of lesser severity and bias in the results.

Respiratory failure was the main cause of death in our population, in line with other series.7 Mortality associated with non respiratory causes like cardiovascular diseases was less frequent; such causes of death are becoming increasingly recognized but are more prevalent in patients with mild-to-moderate COPD (Citation33).

Anemia

Although COPD is “traditionally” associated with polycythemia, our data confirm previous observations that anemia is a frequent finding among these patients, whereas polycytemia has become rarer in COPD (Citation17,Citation34). The prevalence of anemia found in our study population is higher than previously reported in stable COPD patients (Citation13–15,Citation17,18), but in agreement with a recent study conducted on AEPOC patients (Citation16). A possible explanation for this difference could be that during the exacerbation, amplification of inflammatory response typically occurs, both locally and systemically.

It has been postulated that the existence of this increased systemic inflammation may worsen some extrapulmonary manifestations, including anemia (Citation35). In this sense, the anemia could be a phenomenon accompanying the disease severity or a exacerbation-prone phenotype. Even though this may involve an overestimation of anemia, it should be kept in mind that anemia in COPD is usually multifactorial and can also be observed in stability, due to a factors such occult blood loss, treatment with certain drugs (theophylline or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors), and oxygen therapy (Citation36,37). In addition, anemia is a well established prognostic factor in other chronic illnesses that also presents with episodes of acute deterioration such as acute heart failure (Citation38).

To our knowledge, this is the first study that links anemia with mortality in patients with AECOPD. There is only one restrospective report that assessed anemia as a prognostic factor in hospitalized COPD patients; however it was based on critically ill COPD patients whom required invasive mechanical ventilation in ICU. The authors also concluded that anemia was a strong mortality predictor since overall 90-day and mortality among anemic COPD patients was 57.1% versus 25% in nonanemic ones (Citation23).

Our results are similar to those of other studies carried out in stable COPD patients. In the study conducted by Celli et al. (Citation39) to describe BODE score (BMI, airflow obstruction, dyspnea and exercise), Ht also was significantly higher in patients who survived (42 ± 5%) compared with those who died (39 ± 5%). Low Hb and Ht levels have been negatively associated with mortality in patients with LTOT and patients with advanced emphysema severe airflow obstruction (Citation13, Citation21,22).

Exacerbations

There is increasing evidence that exacerbations are not just an epiphenomena of COPD but intrinsically exert a deleterious impact on the natural history of disease (Citation35). The current study is in agreement with previous reports showing that exacerbations are not only an independent marker of mortality, but also that having repeated episodes of these clinical events is probably the largest risk factor for the development of future exacerbations (Citation5,6).

Almagro et al. (Citation7) observed that the need for readmission was an independent risk factor for death in a cohort of patients admitted for COPD exacerbation. In another study performed in a cohort of stable COPD patients, was demonstrated that severe COPD exacerbations constituted a strong risk factor for death independently of other prognostic variables (Citation5).

It is estimated that patients with COPD have, on the average, 1 to 4 exacerbations per year. In our population, patients who died had had 3.5 exacerbations in previous year versus 1.5 exacerbations in the case of the survivors. Although severity of the disease is certainly a factor that influences the onset of exacerbations, there is great interindividual variability among patients.

Data presented from the ECLIPSE study (Citation6) (Evaluation of COPD longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints study) support these clinical observations. In this study, 23% of patients had no worsening during the 3 years of monitoring, while a substantial number of patients had 2 or more exacerbations per year. The authors suggest that these “frequent exacerbators” individuals represent a particular subgroup with increased susceptibility for the coexistence of other factors.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, the follow-up period may be short, but considering the importance of studying patients with frequent readmissions for AECOPD, short-term monitoring can be useful in identifying variables that may be associated with repeated exacerbations. Second, we have attempted to incorporate the prognostic variables most commonly cited in the literature, but some parameters have not been examined (such as estimation of pulmonary artery pressure or exercise tolerance). Despite the recognized importance of these variables on the prognosis of COPD, it can be difficult to measure them during exacerbations. Finally, the etiology of the anemia was not studied; therefore, conclusions cannot be drawn regarding the question of whether etiology of anemia affects its prognostic value. Further studies are needed that specifically address this matter.

Clinical implications

Recent clinical data support the hypothesis that patients with recurrent AECOPD may represent a different phenotypic group (Citation6,Citation40). Therefore, the determination of easily recognizable prognostic variables such as anemia in AECOPD patients has important clinical implications, which can improve the overall management of the disease. As already mentioned, variables reported in the available studies are quite diverse, ranging from clinical or functional parameters, to sociodemographic features (e.g., marital status) (Citation7).

Many of these factors are not modifiable, whereas there are others which may be susceptible to therapeutic interventions. In this sense, although hemoglobin level is a potential modifiable factor, the degree of uncertainty in fundamental aspects, as well as limited available evidence does not establish whether the treatment of anemia will result in improvement in functional outcomes. The influence of this condition on the natural history of COPD should be properly evaluated in further prospective studies.

Summary

In conclusion, in all analyzed variables, anemia, and prior history of exacerbations were independently associated with mortality in patients with AECOPD. Exacerbations can worsen pre-existing conditions, and anemia may be one of these co-morbidities involved. We believe that improved knowledge regarding the variables associated with survival in AECOPD patients is necessary, as these may be at least partly influenced by the interventions of health care and could lead to disease modification and better prognosis.

Declaration of Interest

The authors have reported no potential conflicts of interest. There are no involvement of funding sources in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit the article for publication. Researchers are independent from funders. The authors did not use scientific writing assistance (use of an agency or freelance writer).

References

- Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2009. Global initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) www.goldcopd.com.

- Donaldson GC, Seemungal TAR, Bhowmik A, Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2002; 57(10):847–852.

- Donaldson GC, Wilkinson TMA, Hurst JR, Exacerbations and time spent outdoors in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 171(5):446–452.

- Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Paul EA, Effect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 157(5Pt1):1418–1422.

- Soler-Cataluña JJ, Martínez-García MA, Román Sánchez P, Severe acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 2005; 60(11):925–931.

- Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2010; 363(12):1128–1138.

- Almagro P, Calbo E, Ochoa de Echagüen A, Mortality after hospitalization for COPD. Chest 2002; 121(5):1441–1448.

- Groenewegen KH, Schols AM, Wouters EF. Mortality and mortality-related factors after hospitalisation for acute exacerbation of COPD. Chest 2003; 124(2): 459–467.

- Gunen H, Hacievliyagil SS, Kosar F, Factors affecting survival of hospitalised patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 2005; 26(2):234–241.

- Horwich TB, Fonarow GC, Hamilton MA, Anemia is associated with worse symptoms, greater impairment in functional capacity and a significant increase in mortality in patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39(11):1780–1786.

- Caro JJ, Salas M, Ward A, Anemia as an independent prognostic factor for survival in patients with cancer: a systemic, quantitative review. Cancer 2001; 91(12):2214–2221.

- Silverberg DS, Wexler D, Laina A, The interaction between heart failure and other heart diseases, renal failure, and anemia. Semin Nephrol 2006; 26(2):296–306.

- Chambellan A, Chailleux E, Similowski T, ANTADIR Observatory Group. Prognostic value of hematocrit in patients with severe COPD receiving long-term oxygen therapy. Chest 2005; 128(3):1201–1208.

- John M, Hoernig S, Doehner W, Anemia and inflammation in COPD. Chest 2005; 127(3):825–829.

- John M, Lange A, Hoernig S, Prevalence of anemia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: comparison to other chronic diseases. Int J Cardiol 2006; 111(3):365–370.

- Portillo K, Belda J, Antón P, High frequency of anemia in COPD patients admitted in a tertiary hospital. Rev Clin Esp 2007; 207(8):383–387.

- Cote C, Zilberberg MD, Mody SH, Haemoglobin level and its clinical impact in a cohort of patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 2007; 29(5): 923–929.

- Halpern MT, Zilberberg MD, Schmier JK, Anemia, costs and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2006; 16(4):17.

- Shorr AF, Doyle J, Stern L, Anemia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: epidemiology and economic implications. Curr Med Res Opin 2008; 24(4):1123–1130.

- Krishnan G, Grant BJ, Muti PC, Association between anemia and quality of life in a population sample of individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Pulm Med 2006; 6: 23.

- Lima DF, Dela Coleta K, Tanni SE, Potentially modifiable predictors of mortality in patients treated with long-term oxygen therapy. Respir Med 2011; 105(3):470–476.

- Martínez FJ, Foster G, Curtis JL, et al; NETT Research Group. Predictors of mortality in patients with emphysema and severe airflow obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173(12):1326–1334.

- Rasmussen L, Christensen S, Lenler-Petersen P, Anemia and 90-day mortality in COPD patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Clin Epidemiol 2011; 3:1–5.

- Rodríguez-Roisin R. Toward a consensus definition for COPD exacerbation. Chest 2000; 117(suppl 2):398–401s.

- Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999; 54(3):581–586.

- Ferrer M, Alonso J, Prieto L, Validity and reliability of the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire after adaptation to a different language and culture: the Spanish example. Eur Respir J 1996; 9(6):1160–1166.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, A new method of classifying prognostic co-morbidity inlongitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40(5):373–378.

- Kyle UG, Bosaeus I, De Lorenzo AD, Bioelectrical impedance analysis-part I: review of principles and methods. Clin Nutr 2004; 23(5):1226–1243.

- WHO. Iron deficency anemia: assesment, prevention and control: a guide for program manager. Geneva: WHO; 2001.

- Guralnik JM, Ersshler WB, Schrier SL, Anemia in the elderly: a public health crisis in hematology. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Prog 2005;(1):528–532.

- Seneff MG, Wagner DP, Wagner RP, Hospital and 1-year survival of patients admitted to intensive care units with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA 1995; 274(23):1852–1857.

- Connors AF, Dawson NV, Thomas C, Outcomes following acute exacerbation of severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996; 154(4Pt 1):959–967.

- Sin DD, Anthonisen NR, Soriano JB, Mortality in COPD: role of co-morbidities. Eur Respir J 2006; 28(6):1245–1257.

- Fremault A, Janssens W, Beaucage F, Modification of COPD presentation during the last 25 years. COPD 2010; 7(5):345–351.

- Soler-Cataluña JJ, Martínez-García MA, Catalán Serra P. Impacto multidimensional de las exacerbaciones de la EPOC. Arch Bronconeumol 2010; 46(Suppl.11) :12–19.

- Portillo K. Anemia in COPD: should it be taken into consideration? Arch Bronconeumol 2007; 43(7):392–398.

- Similowski T, Agusti A, MacNee W, The potential impact of anaemia of chronic disease in COPD. Eur Respir J 2006; 27(2):390–396.

- Young JB, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Relation of low hemoglobin and anemia to morbidity and mortality in patients hospitalized with heart failure (insight from the OPTIMIZE-HF registry). Am J Cardiol 2008; 101(2):223–230.

- Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2004; 350(10):1005–1012.

- Han MK, Agusti A, Calverley PM, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes: the future of COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 182(5):598–604.