Abstract

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) coexists with co-morbidities. While co-morbidity has been associated with poorer health status, it is unclear which conditions have the greatest impact on self-rated health. We sought to determine which, and how much, specific co-morbid conditions impact on self-rated health in current and former smokers with self-reported COPD. Using the 2001–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey we characterized the association between thirteen co-morbidities and health status among individuals self-reporting COPD. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) were generated using ordinal logistic regression. Additionally we evaluated the impact of increasing number of co-morbidities with self-rated health. Eight illnesses had significant associations with worse self-rated health, however after mutually adjusting for these conditions, congestive heart failure (OR 3.07, 95% CI 1.69–5.58), arthritis (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.13–2.52), diabetes (OR 1.63, 95% CI 1.01–2.64), and incontinence/prostate disease (OR 1.63, 95% CI 1.01–2.62) remained independent predictors of self-rated health. Each increase in co-morbidities was associated with a 43% higher chance of worse self-rated health (95% CI 1.27-1.62). Individuals with COPD have a substantial burden of co-morbidity, which is associated with worse self-rated health. CHF, arthritis, diabetes and incontinence/prostate disease have the most impact on self-rated health. Targeting these co-morbidities in COPD may result in improved self-rated health.

Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death in the United States, and a cause of significant morbidity and mortality worldwide (Citation1). Recent investigations have illustrated the necessity to view COPD in the context of common co-morbid conditions (Citation2,3), as adults with COPD generally have a higher burden of co-morbid illnesses than their counterparts without COPD (Citation4). Further, COPD is associated with a decrement in quality of life (QOL) and increasing severity of COPD has been shown to adversely impact respiratory–specific QOL (Citation5,6). It is important to understand the contribution of co-morbid conditions to more global and self-assessed measures of QOL such as self-rated health in patients with COPD, while also understanding which specific co-morbid conditions have the greatest impact on self-rated health. Understanding the contribution of co-morbidities to overall health status in COPD may provide insight into how to more appropriately utilize existing treatments in heterogeneous populations, while also helping to inform clinical trial design.

A few publications have shown that the presence of any co-morbid condition is associated with worse health status in COPD (Citation7–10). Prevalent diseases were assessed for their contribution to decreased health status in individuals with COPD in two large cross sectional studies of COPD patients recruited from general practices in the Netherlands (Citation9,10). One small study (Citation11) attempted to characterize the quantitative total burden of co-morbid conditions with regards to the association with health status. However, whether specific co-morbid conditions or an increasing burden of multiple co-morbidities contribute to decreased health status remains largely unknown. Such an understanding could potentially help to increase awareness of multi-morbidity in COPD patients as well as aid in the development of guidelines surrounding the detection for and treatment of co-morbid illnesses in COPD, which do not currently exist.

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a nationally representative sample that captures data on self-reported illnesses and health status (Citation12). This data set provides a unique opportunity to explore the impact of co-morbid conditions on health status in COPD. Based on clinical observations as well as prior publications (Citation2,Citation4,Citation13,14) we assessed 13 co-morbid conditions in our study. First, we identified which of these conditions most substantially worsened self-rated health for individuals with COPD. Further we determined whether a larger burden of multiple co-morbid conditions is associated with worse overall self-rated health compared to few or no co-morbid conditions. We hypothesized that while increasing numbers of co-morbidities would be associated with worse self-rated health, certain conditions would contribute more to decreased health status, particularly those that are associated with symptoms of dyspnea and functional limitation such as congestive heart failure, depression, and arthritis.

Methods

Survey sample

We utilized publicly available data from continuous NHANES survey between 2001–2008, using a subpopulation with self-reported COPD age 45 years and older. NHANES (Citation12) is a multistage complex probability sample of the non-institutionalized population of the United States, which surveys roughly 15 counties yearly. Subjects undergo a detailed interview, examination, and laboratory testing (Citation15). Appropriate analytic weights were constructed (Citation16). COPD was defined via self-report, as any affirmative response to the questions “has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you had…?” for either emphysema or chronic bronchitis, and a history of smoking at least 100 cigarettes in one's lifetime. A history of smoking 100 cigarettes in one's lifetime was included in the definition of COPD in order to reduce misclassification of asthmatics and those with other lung diseases as individuals with COPD. Based upon documentation from NHANES, data from roughly 41,658 interviewed individuals were included in the survey between 2001–2008 (Citation17).

Definition of co-morbid conditions

We defined co-morbid conditions to include medical diagnoses as well as health states and conditions that confer risk for overall worse health, symptomatology and mortality and could potentially contribute to worse health status. Thirteen co-morbid conditions were assessed: coronary heart disease (CHD), diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), history of stroke, congestive heart failure (CHF), arthritis, history of cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer), obesity, liver disease, use of antidepressants or report of depressed symptoms, anemia, asthma and presence of incontinence or prostate disease. Co-morbid conditions were defined with self-report; however, in some cases, additional survey questions, measurements or laboratory values were incorporated into the definitions, as shown in Table E1. We were only able to assess those co-morbid conditions described in the NHANES survey. We accounted for confounding by age, gender, and race (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other).

Measurement of outcomes

The outcome is self-rated health, measured by the CDC Health Related Quality of Life-4 (HRQOL-4) instrument (Citation18), a four-part instrument administered since 2001. The outcome was quantified using the summary measure of self-rated health which asks “Would you say that in general your health is: Excellent, Very good, Good, Fair or Poor?”

Statistical analyses

We detail the handling of missing data in the Online Supplement. The outcome was analyzed using ordinal logistic regression, with 5 levels for the graded responses to the question regarding self-rated health. Individuals with greater than or equal to 3 co-morbid conditions were examined for differences in baseline characteristics compared to those with less than three co-morbid conditions using chi-square tests (for categorical variables) and simple linear regression (for continuous measures), as defined in the online supplement. Next, we performed ordinal logistic regression to assess the association between each individual condition and the outcome of self-rated health, adjusted for age, gender, and race.

We also wanted to understand each co-morbid conditions contribution to explaining self-rated health within the context of other conditions. We performed mutually adjusted analyses using all conditions found to have a significant association with self-rated heath in the separate adjusted regressions above.

To assess the extent to which multiple co-morbid conditions contribute to decreased health status compared to no or few illnesses, we 1) employed a simple count of the number of co-morbid conditions for each individual and 2), constructed a co-morbidity score, weighting each condition by its exponentiated coefficient from the adjusted regressions of each individual condition with self-rated health. Each of these measures was analyzed for its association with self-rated health in adjusted ordinal logistic regression models.

Stata 12 statistical software package was used (Citation19). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Institutional Review Board at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine approved this analysis.

Results

Description of the survey sample

We first compared self-rated health in individuals age 45 and older with and without self-reported COPD (based upon our definition outlined above) in the survey sample. We found that a significantly larger proportion of individuals without self-reported COPD reported excellent (11.7% compared to 3.1% in those with COPD, p < 0.001) and very good health status (33.5% compared to 14.1% in those with COPD, p < 0.001), while individuals with self-reported COPD more commonly reported good, fair or poor health status (15.5% of those with COPD had poor health status compared to 3.5% of those without COPD, p < 0.001). Further, we compared the burden of co-morbidities in adults 45 years of age and older with and without self-reported COPD. We found that there were far fewer adults with self-reported COPD who reported no co-morbid conditions compared to those without COPD (3.2% vs 9.5%, p < 0.001), while generally individuals with self-reported COPD reported more co-morbid conditions than those without COPD, all statistically significant findings.

Self-reported COPD (as defined above) had a prevalence of 6.7% in the subpopulation of individuals 45 years of age and older (including roughly 843 surveyed individuals in the sample). This subpopulation was 47.4% male, with 83.3% being Non-Hispanic White (with 8.7% Non-Hispanic Black, 3.7% Hispanic, and 4.2% Other Race). The average age of the sample was 62.4 years (95% CI 61.4–63.4), while 43.9% were current smokers and 56.1% former smokers.

details the underlying characteristics of individuals with self-reported COPD comparing those with less than 3 and 3 or more co-morbid conditions, given that 3 was the median and mean number of co-morbid conditions in the sample. A larger proportion of the group with 3 or more co-morbid conditions were less formally educated (had less than a high school diploma), a difference that did reach statistical significance. Despite lack of statistically significant differences between gender and race of these groups, analyses were adjusted for these variables as well as age based upon an a priori hypothesis of confounding from these sources.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of COPD patients age 45 and older with<3 and > = 3 co-morbidities

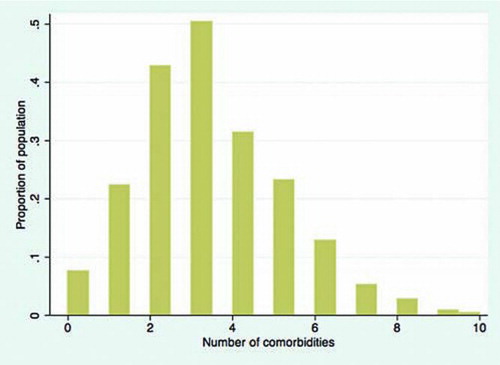

Co-morbid conditions were prevalent in this population of adults with self-reported COPD. Specifically, 83.6% of individuals had more than 2 co-morbid conditions, yet 4.3% had zero self-reported co-morbid conditions. The mode was 3 co-morbid conditions (present in roughly 50% of the sample) and the maximum number of co-morbid conditions (out of the 13 analyzed) was 10. displays the overall distribution of this count in the study population. displays prevalence estimates for each separate co-morbidity in the study sample. Some conditions were quite prevalent and present in close to or over half of the study sample, such as incontinence or prostate disease, depressive symptoms, and obesity; while others such as anemia and liver disease were present in less than 10%.

Figure 1. Histogram of co-morbidity count (range 0–13) among individuals 45 years of age and older with self-reported COPD.

Table 2. Prevalences of co-morbidities in study population (self-reported COPD age 45 and older)

Associations of each co-morbid condition with self-rated health

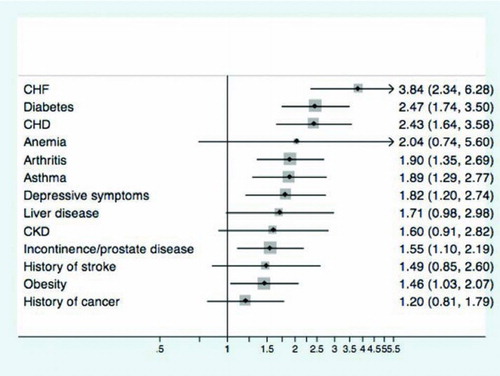

Adjusted odds ratios of the association between each co-morbid condition and self-rated health were calculated and results are displayed in . Of the 13 examined conditions, eight had notable associations with worse self-rated health including CHF (OR 3.84, 95% CI 2.34–6.28), diabetes (OR 2.47, 95% CI 1.74–3.50), CHD (OR 2.43, 95% CI 1.64–3.58), arthritis (OR 1.90, 95% CI 1.35–2.69), asthma (OR 1.89, 95% CI 1.29–2.77), use of antidepressant/depressive symptoms (OR 1.82, 95% CI 1.20–2.74), urinary incontinence/prostate disease (OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.10–2.19), and obesity (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.03–2.07).

Independent associations of co-morbid conditions with self-rated health

We analyzed the outcome of self-rated health with all co-morbid conditions that had a statistically significant association with self-rated health (CHD, CHF, diabetes, use of antidepressant/depressive symptoms, arthritis, asthma, urinary incontinence/prostate disease and obesity) while controlling for age, gender, and race. After controlling for other co-morbid conditions statistically associated with self-rated health, CHF (OR 3.07, 95% CI 1.69–5.58), arthritis (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.13–2.52), incontinence/prostate disease (OR 1.63, 95% CI 1.01–2.62), and diabetes (OR 1.63, 95% CI 1.01–2.64) continued to have significant associations with self-rated health. CHD, depressive symptoms, asthma and obesity were no longer associated with self-rated health ().

Table 3. ORs for worse health status with all independently associated co-morbidities, adjusted for age, gender and race

Impact of increasing co-morbid conditions on self-rated health

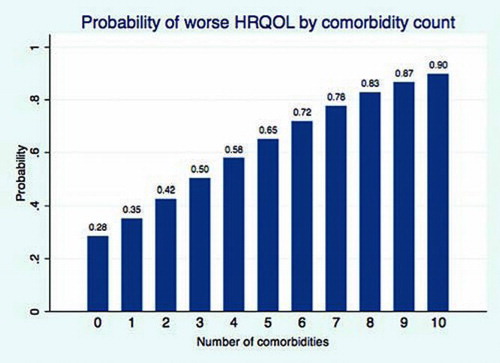

For every increase in co-morbid condition by one, the odds of worse self-rated health increased by 43% (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.27–1.62). displays the effect of increasing co-morbidities on self-rated health. One can see a nearly linear increase in probability of worse health status with increasing number of co-morbid conditions, with the mode of 3 conditions being associated with 50% chance of worse health status, and the maximum of 10 co-morbid conditions associated with 90% probability of worse health status. displays means (with standard deviations) and medians for the self-rated health measures stratified by number of co-morbidities. Mean self-rated health score (range Citation1–5) increases with increasing number of co-morbid conditions. Zero co-morbid conditions was associated with a mean self-rated health of good, and 8 conditions was on average associated with between good and fair health status, and 10 conditions with between fair and poor health status. Overall, and show that as number of co-morbid conditions increases, self–rated health in this subpopulation decreases incrementally.

Figure 3. Probability of worse self-rated health (fair or poor versus good, very good, or excellent) by co-morbidity count, adjusted for age, gender, and race using logistic regression.

Table 4. Mean and median self-rated health scoresa, by co-morbidity countb

Association of weighted co-morbidity score with self-rated health

A co-morbidity score was constructed using the adjusted ORs in to effectively weight each co-morbid condition based upon its independent association with self-rated health. Mean weighted co-morbid score was 6.13 (95% CI 5.78–6.48). Results of this analysis as well as equation for calculation of the co-morbidity score are displayed in Table E2 in the online supplement. Each increase in weighted co-morbidity score by one point was associated with 1.22 times higher odds of worse self-rated health (95% CI 1.15–1.29).

Discussion

Using the NHANES survey that is representative of the non-institutionalized US population, we have shown that individuals with self-reported COPD have a high burden of co-morbid chronic illness. In addition, we have demonstrated that CHF, diabetes, CHD, arthritis, asthma, urinary incontinence/prostate disease, depressive symptoms, and obesity are of particular importance in their contribution to a worse health status in the adult population with COPD. Of these, CHF, arthritis, incontinence/prostate disease and diabetes are independently associated with self-rated health after adjusting for all other important co-morbid conditions. Further, we have illustrated that an increasing burden of co-morbid conditions is associated with worse self-rated health in the setting of COPD.

Our observation that there exists a substantial burden of co-morbid conditions in individuals with COPD supports previous investigations showing that adults with COPD have a significant burden of co-morbidity. An investigation of the National Hospital Discharge Survey between 1979 and 2001 showed a higher in-hospital prevalence and mortality due to hypertension, CHD, diabetes, pneumonia, CHF, kidney failure, peripheral vascular disease, and thoracic malignancy in individuals with primary or secondary diagnoses of COPD during hospitalization compared to those without a diagnosis of COPD (Citation2). Analysis of a British outpatient survey sample also showed that individuals with COPD had a higher prevalence of co-morbid conditions such as CHD, diabetes, and history of stroke than those without COPD (Citation13).

A recent study of a similar NHANES sample as used in our investigation (though encompassing different years) also shows a higher burden of many co-morbid conditions and clinical factors in individuals with self-reported COPD compared to those without (Citation4). We have shown that in this nationally representative sample, co-morbid conditions are prevalent in individuals with COPD in the out-of-hospital setting. The risk factor of smoking could account for the high prevalence of co-morbidities such as cardiovascular conditions among those with COPD, particularly in this sample with a high percentage of current smokers. However, the high prevalence of all co-morbidities including arthritis, depression, incontinence and diabetes suggests that a larger, overarching systemic process, related or unrelated to smoking, could account for the multi-morbidity of patients with COPD.

Our second important finding is that particular co-morbid conditions contribute to decreased health status in the setting of COPD, and specifically CHF, arthritis, incontinence/prostate disease and diabetes have the most impact. A clear association has been shown between the presence of CHF and mortality in the setting of COPD (Citation22,23). Another study showed that CKD, chronic liver disease, and CHD were independent predictors of death among individuals with COPD after hospitalization (Citation24). Although several studies have evaluated the impact of co-morbid conditions on mortality in COPD, few have evaluated patient-reported outcomes such as self-rated health.

A few previous studies have shown associations between arthritis (Citation10), dizziness, and history of stroke (Citation9) with lower health status in the setting of COPD. We have illustrated that CHF, diabetes, CHD, arthritis, asthma, urinary incontinence/prostate disease, depressive symptoms, and obesity are independently associated with worse self-rated health in COPD. The importance of CHD, CHF, arthritis, and depressive symptoms may be related to these diseases effects on dyspnea, functional capacity, fatigue, perception of symptomatology and coping skills.

The contribution of diabetes is intriguing and challenges us to better understand this relationship by examining the interaction of the systemic activity of diabetes with COPD. It has been proposed that the microvascular changes impacting organs such as the kidney and heart in diabetes may also affect the lungs, causing changes in lung function and diffusion capacity (Citation25,26). Such a hypothesis could potentially explain increased symptoms in diabetics with COPD. Future studies should seek to better understand the possible interaction between these two diseases.

The finding that an increasing burden of co-morbid conditions is associated with worse self-rated health has not been shown in a large study or survey sample. A few studies have shown the presence of any co-morbid illness is associated with worse health status (Citation7–10). One small study of 27 subjects from an outpatient center in England showed a positive correlation between increasing co-morbidity symptom scale and worse quality of life, as measured by the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (Citation11). We have successfully shown in a large survey sample that, in individuals with self-reported COPD, as number of co-morbid conditions increases, self-rated health significantly decreases. These findings imply that indentifying and managing co-morbid conditions in COPD can potentially improve health status outcomes.

This study has limitations. The analysis is based upon a survey sample of the population that was performed in a cross-sectional fashion and as such, there is always a potential for reverse causality. Further, because our study sample is a subpopulation of the NHANES sample, it is less likely to be truly representative of the non-institutionalized U.S. population as NHANES was intended. Such a limitation impacts the prevalence estimates for co-morbidities in our subsample, however the generalizability of our estimates of association between co-morbidities and self-rated health should be less impacted by this limitation.

However, the small proportion of African Americans in the subsample does somewhat impact the generalizability of our findings. Also, the use of self-report for the characterization of COPD and co-morbid conditions could lead to misclassification. For co-morbid conditions, this leads to some likely misclassification, but in some chronically ill populations self-report has been shown to be reasonably valid compared to medical record-based algorithms (Citation27).

It has been shown that despite the definition for COPD (based upon patient report, spirometry, symptom-based, or expert opinion), there has historically been significant variation in the prevalence estimates for COPD, and generally, COPD prevalence is considered to be underestimated in the general population (Citation28). Our use of self-report to define COPD may have led us to underestimate COPD in our study sample. In addition, it is possible that some individuals reporting a diagnosis of asthma in fact have COPD and vice versa.

However, previous studies have shown that most people reporting a diagnosis of COPD truly do have this condition when verified by more complete medical records including radiographic data and pulmonary function tests (78–86% in one population of nurses (Citation29), and 93% of patients presenting to emergency departments with symptoms of acute exacerbations of COPD [30]). Regardless, because the severity of COPD can contribute to reduced quality of life and health status, our inability to adjust for COPD severity serves as a limitation on our estimates of the contribution of co-morbidities to quality of life in COPD.

Ultimately, there is a tradeoff between the breadth and representativeness of such a large survey sample with the lack of detailed information on doctor diagnoses or detailed testing that makes confirming self-report difficult. Further, we used a surrogate measure for depression due to the lack of consistent instruments used over the survey years (Citation31). Although the use of surrogate measures for depression such as symptom scores (Citation32) and antidepressant use (Citation33) have been previously demonstrated, such an approach could result in some misclassification of the presence of depression.

In addition, we utilized a generic instrument to measure the outcome of health status, an approach which some may consider limited. Although this measure is not specific to COPD or pulmonary diseases, the use of a generic measure was preferred due to concerns that respiratory disease-specific quality of life instruments would not adequately capture the impact of non-pulmonary co-morbid conditions. Finally, we were limited in our ability to assess the presence of only those conditions inquired about in the NHANES survey, though we believe we have included conditions expected to have the highest prevalence in this population (Citation4), while also having an impact on self-rated health.

Regardless, conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, which have been shown to be associated with quality of life (Citation34) and exacerbation risk (Citation35) in COPD, were not assessed in the NHANES survey. Further, because the NHANES data provides no information on severity of co-morbid conditions, we were unable to account for varying severity of these conditions. Similarly, not adjusting for pharmacologic treatment of COPD and co-morbidities prevents the assessment of how treatments and polypharmacy can impact upon self-rated health in multi-morbid individuals with COPD.

Conclusions

COPD has a course that is progressive (Citation36) and is associated with poor self-rated health (Citation6). Knowing that co-morbid conditions are common in COPD, identifying how these conditions contribute to poorer self-rated health is essential, particularly with the increasing recognition of the relevance of patient important outcomes. Clinicians are often faced with decisions regarding simplification of medication regimens, particularly as patients age and regimens become complicated due to multi-morbidity (Citation37). Understanding the relative importance of different co-morbid illnesses in determining self-rated health can help direct interventions for these complicated patients. In our analysis, individuals with COPD have a high prevalence of co-morbid chronic illness. CHF, anemia, diabetes, CHD, arthritis, incontinence or prostate disease and depressive symptoms appear to contribute to worse health status in COPD patients, however CHF, DM and arthritis were independently associated with poor self-related health.

Therefore, therapies targeting the treatment of CHF, DM and arthritic symptoms may have the greatest impact on improving perceived health in patients with COPD. Further, information gained by understanding the relative contribution of different co-morbidities to self-related health can be used in the development of COPD-specific instruments to measure relevant co-morbidities that can ultimately contribute to prediction of not only self-rated health but also outcomes such as dyspnea, exercise capacity, and mortality.

Declaration of Interest Statement

The authors have no financial, consulting, or personal relationships with people or organizations to disclose that could influence the work outlined above.

Appendices

Please find included as a separate attachment supplementary online material referenced in this article.

Acknowledgments

The work contained in this manuscript was completed in part as thesis work for Dr. Putcha's Masters program in Epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The abstract for this paper was presented at the American Thoracic Society conference in May, 2012.

Author Support: NP: NIH T32HL007534 (research fellow).

MAP: Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research 5UL1RR025005-04, Xurich Lung League (Switzerland) and Dutch Astma Fond (Netherlands), European Union Framework Programme 7, National Center for Research Resources.

NNH: NIEHS/EPA P01 ES018176, Housing and Urban Development, NIH Prime Subaward SPIROMICS, NIH 1P50HL084945-01, NIH 1P50ES015903-01

MBD: NIH-NHBLI K23HL103192.

CMB: The Johns Hopkins Bayview Center for Innovative Medicine, The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Physician Faculty Scholars Program, the Paul Beeson Career Development Award Program (NIA K23 AG032910, AFAR, The John A. Hartford Foundation, The Atlantic Philanthropies, The Starr Foundation and an anonymous donor), and AHRQ R21 HS018597-01 (PI).

References

- Miniño AM, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD. Deaths: Final Data for 2008. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 59 no 10. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2011.

- Holguin F, Folch E, Redd SC, Mannino DM. Co-morbidity and mortality in COPD-related hospitalizations in the United States, 1979 to 2001. Chest 2005; 128(4):2005–2011.

- Ekstrom MP, Wagner P, Strom KE. Trends in cause-specific mortality in oxygen-dependent Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2011; 183(8):1032–1036.

- Schnell KM, Weiss CO, Lee T, Krishnan JA, Leff B, Wolff JL, Boyd CM. The prevalence of clinically-relevant co-morbid conditions in patients with COPD: a cross-sectional study using data from NHANES 1999–2008. BMC Pulmon Med, in press.

- Marin JM, Cote CG, Diaz O, Lisboa C, Casanova C, Lopez MV, Carrizo SJ, Pinto-Plata V, Dordelly LJ, Nekach H, Celli BR. Prognostic assessment in COPD: Health related quality of life and the BODE index. Respir Med 2011; 105(6):916–921.

- Eskander A, Waddell TK, Faughnan ME, Chowdhury N, Singer LG. BODE index and quality of life in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease before and after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2011;2011 Dec; 30(12):1334–1341.

- Ferrer M, Alonso J, Morera J, Marrades RM, Khalaf A, Aguar MC, Plaza V, Prieto L, Antó JM. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease stage and health-related quality of life. The Quality of Life of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1997; 127(12):1072–1079.

- van Manen JG, Bindels PJ, Dekker FW, Bottema BJ, van der Zee JS, Ijzermans CJ, Schadé E. The influence of COPD on health-related quality of life independent of the influence of co-morbidity. J Clin Epidemiol 2003; 56(12):1177–1184.

- van Manen J, Bindels P, Decker F Added value of co-morbidity in predicting health-related quality of life in COPD patients. Respir Med 2001; 95:496–504.

- Wijnhoven HA, Kriegsman DM, Hesselink AE, de Haan M, Schellevis FG. The influence of co-morbidity on health-related quality of life in asthma and COPD patients. Respir Med 2003; 97(5):468–475.

- Yeo J, Karimova G, Bansal S. Co-morbidity in older patients with COPD–its impact on health service utilisation and quality of life, a community study. Age Ageing 2006; 35(1):33–37.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm.

- Feary JR, Rodrigues LC, Smith CJ, Hubbard RB, Gibson JE. Prevalence of major co-morbidities in subjects with COPD and incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke: a comprehensive analysis using data from primary care. Thorax 2010; 65(11):956–962.

- Weiss CO, Boyd CM, Yu Q, Wolff JL, Leff B. Patterns of prevalent major chronic disease among older adults in the United States. JAMA 2007; 298(10):1160–1162.

- CDC. July 21, 2009. About the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. CDC website. Retrieved 4/12/11, from, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm

- September 29, 2010. Specifying weighting parameters. CDC website. Retrieved 4/12/11 from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/Nhanes/SurveyDesign/Weighting/intro.htm.

- NHANES Response Rates and CPS Totals. CDC website. Retreived 4/12/11. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/response_rates_CPS.htm.

- CDC. Measuring healthy days: population assessment of health-related quality of life. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; November 2000. Downloaded from: http://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/methods.htm on August 12, 2011.

- StataCorp. 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

- Benowitz NL, Bernert JT, Caraballo RS, Holiday DB, Wang J. Optimal serum cotinine levels for distinguishing cigarette smokers and nonsmokers within different racial/ethnic groups in the United States between 1999 and 2004. Am J Epidemiol 2009; 169(2):236–248.

- Zhang Y, Post WS, Dalal D, Blasco-Colmenares E, Tomaselli GF, Guallar E. Coffee, Alcohol, Smoking, Physical Activity and QT Interval Duration: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. PLoS One 2011; 6(2):e17584.

- Almagro P, Calbo E, Ochoa de Echaguen A, Mortality after hospitalization for COPD. Chest 2002; 121:1441–1448.

- Boudestein LC, Rutten FH, Cramer MJ, Lammers JW, Hoes AW. The impact of concurrent heart failure on prognosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur J Heart Fail 2009; 11(12):1182–1188.

- Antonelli-Incalzi R, Fuso L, De Rosa M, Co-morbidity contributes to predict mortality of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 1997; 10:2794–2800.

- Ljubic S, Metelko Z, Car N, Roglic G, Drazic Z. Reduction of diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide in diabetic patients. Chest 1998; 114:1033–1035.

- Guvener N, Tutuncu NB, Akcay S, Eyuboglu F, Gokcel A. Alveolar gas exchange in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr J 2003; 50:663–667.

- Halbert RJ, Isonaka S, George D, Iqbal A. Interpreting COPD prevalence estimates: what is the true burden of disease? Chest 2003; 123(5):1684–1692.

- Simpson CF, Boyd CM, Carlson MC, Griswold ME, Guralnik JM, Fried LP. Agreement between self-report of disease diagnoses and medical record validation in disabled older women: factors that modify agreement. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52(1):123–127.

- Barr RG, Herbstman J, Speizer FE, Camargo CA Jr. Validation of self-reported chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a cohort study of nurses. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 155(10):965–971.

- Radeos MS, Cydulka RK, Rowe BH, Barr RG, Clark S, Camargo CA Jr. Validation of self-reported chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among patients in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2009; 27(2):191–196.

- Freeman EJ, Colpe LJ, Strine TW, Dhingra S, McGuire LC, Elam-Evans LD, Public health surveillance for mental health. Prev Chronic Dis 2010; 7(1):A17. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2010/jan/09_0126.htm. Accessed 12/15/2011.

- Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, Hewitt C. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): a diagnostic meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22(11):1596–1602.

- Trinh NH, Youn SJ, Sousa J, Regan S, Bedoya CA, Chang TE, Fava M, Yeung A. Using electronic medical records to determine the diagnosis of clinical depression. Int J Med Inform 2011; 80(7):533–540.

- Rascon-Aguilar IE, Pamer M, Wludyka P, Cury J, Vega KJ. Poorly treated or unrecognized GERD reduces quality of life in patients with COPD. Dig Dis Sci 2011; 56(7):1976–1980.

- Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, Locantore N, Müllerova H, Tal-Singer R, Miller B, Lomas DA, Agusti A, Macnee W, Calverley P, Rennard S, Wouters EF, Wedzicha JA; Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) Investigators. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2010; 363(12):1128–1138.

- From the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2011. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/.

- Tinetti ME, McAvay GJ, Chang SS, Newman AB, Fitzpatrick AL, Fried TR, Peduzzi PN. Contribution of multiple chronic conditions to universal health outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59:1686–1691.