Abstract

A scoping review was conducted to determine the size and nature of the evidence describing associations between social support and networks on health, management and clinical outcomes amongst patients with COPD. Searches of PubMed, PsychInfo and CINAHL were undertaken for the period 1966–December 2013. A descriptive synthesis of the main findings was undertaken to demonstrate where there is current evidence for associations between social support, networks and health outcomes, and where further research is needed. The search yielded 318 papers of which 287 were excluded after applying selection criteria. Two areas emerged in which there was consistent evidence of benefit of social support; namely mental health and self-efficacy. There was inconsistent evidence for a relationship between perceived social support and quality of life, physical functioning and self-rated health. Hospital readmission was not associated with level of perceived social support. Only a small number of studies (3 articles) have reported on the social network of individuals with COPD. There remains a need to identify the factors that promote and enable social support. In particular, there is a need to further understand the characteristics of social networks within the broader social structural conditions in which COPD patients live and manage their illness.

Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) can result in significant and disabling psychological distress and social isolation, for both males and females, and younger as well as older persons (Citation1). The main symptoms of COPD are dyspnoea, fatigue and cough, which can have significant impacts on activities of daily living and quality of life (Citation2). Significant advances have been made in the past decade toward understanding the impact of COPD on psychological distress and mental health and the role of these factors in management and outcomes of COPD (Citation3, Citation4); but no reviews have been written to consolidate our understanding of the impact of COPD on social relationships, and how social relationships, including social support and social networks, impact management and outcomes in COPD.

Over the past 30 years there has been increasing empirical evidence supporting the important role of social relationships in mediating health outcomes. For example a recent meta-analysis of all-cause mortality found that individuals with adequate social relationships have a 50% greater likelihood of survival compared to those with poor or insufficient social relationships (Citation5). This effect is comparable with other well-established risk factors for mortality such as smoking and alcohol consumption and exceeds the influence of other risk factors such as physical inactivity and obesity (Citation5). Studies investigating disease outcomes other than mortality have shown a beneficial effect of perceived social support for conditions such as coronary heart disease in terms of both development and prognosis (Citation6) and that larger social networks are associated with positive health outcomes and decreased incidence of cardiovascular disease (Citation7).

Several theoretical and conceptual models have been proposed to explain processes through which social factors may influence health. The first of these emerged in the 1980s following social research published in the 1970s demonstrating associations between social support and disease aetiology and mortality. One influential model known as the “stress buffering and main effects models” proposed by Cohen and colleagues envisions social support ‘buffering’ individual well-being from the potentially pathogenic influence of stressful events (Citation8, Citation9). A second theory known as the main-effects model, proposes that social resources have beneficial effects irrespective of whether a person is under stress or not. This theory underlies explanations of results from recent meta-analyses that determined an overall effect size corresponding with a 50% increase in odds of survival as a function of social relationships (Citation5).

However, Cohen's model (and other models that emphasise the role of social support) doesn't take into consideration the importance of characteristics of social networks and the macro social environment that social support occurs within. These “upstream” social factors form part of a broader conceptualisation of how social relationships impact upon health proposed by Berkman and Glass (Citation10). In their model, Berkman and Glass envision a cascading causal process whereby the macro-social context conditions the structure of social networks. The social network structure and function influence social and interpersonal behaviours including social support, which in turn influence more proximate pathways to health status. These proximate pathways included 1) direct physiological stress responses; 2) psychological states and traits; and 3) health damaging behaviours such as tobacco consumption (Citation11).

COPD has long been known to impact negatively upon social roles and place individuals at risk of social isolation, which may diminish confidence in their ability to self-manage their illness (Citation12). Disler et al.’s (Citation12) review highlights the social influences impacting self-management of COPD including social isolation, loss of social role and social support and how these interact with physical, psychological, existential and other social determinants to influence self-care behaviour (Citation12). However, despite an increasing body of evidence describing associations between social relationships and important outcomes in COPD there have not been any published reviews assimilating this literature.

We began by asking: what do we know about the social relationships of patients with COPD and what are the health impacts of these relationships? An initial search of the literature did not identify any review articles addressing the issue of social relationships and health outcomes amongst patients with COPD. Consequently a scoping review was conducted in order to identify gaps in the literature and make recommendations for future primary research. Scoping studies differ from standard systematic reviews in that they do not attempt to synthesise the evidence but are used to determine the size and nature of the evidence base for a particular topic area. This approach is particularly useful when the aim is to identify gaps in the literature and make recommendations for future primary research (Citation13).

The aim of this review was to determine the size and nature of the evidence describing associations between perceived social support and social networks on health, management and clinical outcomes amongst patients with COPD.

Methods

A preliminary search of the literature was first conducted using broad terms such as “social” AND “COPD.” From the articles identified it was apparent that most studies assessed aspects of social support and to a lesser extent, social networks. The search also revealed that both qualitative and quantitative methods were used. Guided by both the frameworks we previously identified that linked social relationships to health outcomes and this first pass search of the literature, it was decided that a more focussed search was the most useful way forward, focussing on quantitative assessment of social support and social networks.

Focussed searches of PubMed, PsychInfo and CINAHL, and inspection of reference lists of relevant papers for the period 1966–December 2013 was then undertaken by one author (CB). The databases were searched for all articles using the terms (“social* support*” or “social* isolation*” or “social* network*”) AND COPD. No reviews specifically addressing the impact of social relationships on relevant outcomes amongst patients with COPD were identified, but relevant related review papers were sourced and checked for additional papers meeting our selection criteria.

Peer-reviewed studies written in English, German or Dutch languages were considered for inclusion. Articles were excluded when outcomes were not reported independently for social support or social network (for example if only a full regression model was reported), or if results for COPD patients were not reported separately to those of participants with other chronic illnesses (including asthma). Further, if outcomes were only focussed on smoking cessation or caregivers the study was excluded. Studies that reported social function or social isolation only as part of a quality-of-life instruments (such as the SF 36 or Nottingham Health Profile) were also excluded.

Our focus was on studies that measured and reported outcomes for social support or social networks using instruments or questions designed to assess these variables. These included both functional measures of social support (Citation6) (or perceived social support) and structural support in the form of social networks. Social support measures assess resources provided by others (Citation8, Citation9) and can include dimensions of emotional, instrumental, appraisal and informational supports (Citation10, Citation14). The term social network refers to the web of relationships that surround an individual (Citation10) and in particular the structural features such as the type and strength of each social relationship (Citation15).

We excluded studies that only used marital status or living arrangements as a measure of structural support. We decided to focus on the measurement of the perceived availability of functional support because of our belief that a person's perceptions about available support are most important (Citation16) and the difficulty in determining how marital status was assessed and recorded in individual studies. We have only reported the findings from quantitative studies here; results from qualitative studies will be reported elsewhere as part of a meta-synthesis, mostly due to difficulty in integrating the findings from these different study types in a coherent manner with findings from the quantitative studies.

Data extraction tables were developed by the authors and then information from papers was initially extracted by one author (CB). The accuracy of this information was then independently verified by the other 2 co-authors (TE and PC). Any disputes were resolved by discussion amongst the 3 authors. As this was a scoping study we did not attempt meta-analysis but we provide a descriptive synthesis of the main findings to demonstrate where there is current evidence for associations between social relationships and health outcomes. Conversely, we are also able to highlight where further research is needed to determine an association between social relationships and health outcomes (Citation13).

Results

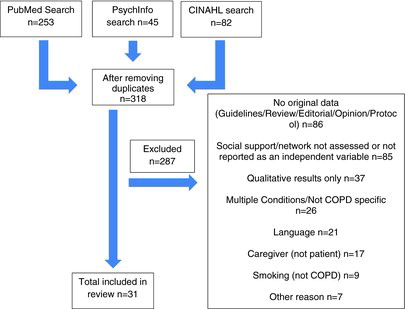

The search yielded 253 articles from PubMed; 82 from CINAHL and 45 from PsychInfo. After removing duplicates a total of 318 papers were considered for inclusion in the review, of which 287 were excluded following a reading of the title and/or abstract for relevance and applying selection criteria, leaving a final number of 31 papers that were included (See Figure ).

Figure 1. Flow chart depicting selection of papers for inclusion in the review and reasons why papers were excluded.

The included articles described a range of outcomes against which the impact of social support and social networks were assessed. These were grouped for data extraction into studies reporting on either the effect of social support (Tables –) or social networks (Table ).

Table 1. Impact of social support on mental health

Social support

Studies describing relationships between perceived social support and health outcomes are summarised in Tables –. There were 2 areas in which there was consistent evidence of benefit of social support for patients with COPD; namely mental health (Table ) and self-efficacy (Table ). Twelve studies were identified that reported benefits of social support for COPD patients with depression (9 studies) (Citation17–Citation25), anxiety (2 studies) (Citation25, Citation26), psychological distress or stress (2 studies) (Citation27, Citation28) in community, outpatient and in-patient hospital settings (Table ).

Table 2. Impact of social support on self-efficacy and adherence

Self-efficacy and self-care behaviour (including adherence) was also consistently found to be better when study participants reported better social support (Table ). Five of seven studies reported positive associations [and one of the negative studies found benefits in univariate analyses but the relationship failed to reach statistical significance in multi-variate analyses (Citation29)]. Three studies reported positive relationships between social support and self-efficacy (Citation19, Citation30, Citation31) and studies from Xiaolian et al. (Citation32) and Kara-Kasickci et al. (Citation30) reported positive associations with self-care behaviour. One further study [Young et al. (Citation33)] reported adherence to a pulmonary rehabilitation program was higher amongst patients with better social support.

There was inconsistent evidence for a relationship between social support and the variables of functional status, quality of life, and self-rated health (Table ). The study from Arne et al. (Citation34) comprising a community sample of 1,475 patients with COPD found that social support and the absence of economic problems almost doubled the odds for better self-rated health and quality of life. However, the occurrence of COPD in this study was self-reported rather than objectively assessed and the assessment of social support was based only on a single question (Do you have any persons in your vicinity that can provide you with personal support in case of personal problems or life crises?). One other study [Marino et al. (Citation35)] found that amongst 156 depressed COPD patients admitted to hospital, overall functioning as assessed by the WHO disability assessment schedule II was predicted by subjective social support assessed by the Duke Social Support Inventory.

Table 3. Impact of social support on functional status, quality of life and self-rated health

Table 3. (Continued)

Readmission following hospital discharge for treatment of COPD (3 studies) (Table ) was not associated with level of perceived social support. One study reported mixed benefits of social support in terms of reduced risk of mortality amongst patients following a program of pulmonary rehabilitation (benefits for females but not males) (Table ).

Table 4. Impact of social support on hospital re-admission and mortality

Social networks

Only three studies met our selection criteria that have reported on the social network of individuals with COPD (Table ) and only one study [Marino et al. (Citation35)] was published in the past decade. The study by Grodner et al. (Citation19) found positive relationships between the number of persons in the COPD patient's social network and self-efficacy for walking, disease severity, exercise tolerance and self-reported shortness of breath and a negative correlation with depression symptoms. In this study, following a program of pulmonary rehabilitation, the number of persons in the patients social network was associated with improved breathlessness after 2, 6 and 12 months of follow up. Marino et al. (Citation35) found social network size measured using the Duke Social Support Inventory to be associated with overall functioning in bivariate analyses, but this relationship just failed to reach statistical significance in multi-variate analyses. Finally, Keele-Card and Barron (Citation36) found no relationship between the number of people in the COPD patient's social network and reports of loneliness or depression (Table ).

Table 5. Social networks and COPD

Discussion

This scoping review started with a broad question: what do we know about the health impacts of social relationships for patients with COPD? The search criteria and inclusion criteria were deliberately kept broad in order to facilitate the inclusion of the largest number of studies possible. This approach enabled the determination of the size and nature of the evidence which in turn allowed us to identify gaps in the literature and make recommendations for future primary research. Following an initial inspection of the literature we focussed on studies reporting associations with perceived social support and social networks. Most of the identified literature was concerned with ‘perceived’ social support. Clear trends emerged in terms of the outcomes that benefit from social support. There were benefits for mental health and sense of self-efficacy, but inconsistent support was found in terms of quality of life, functional status, and hospital readmission. From the literature identified, little can be determined about where this perceived social support is derived and the characteristics of the social network of COPD patients.

Much of the research investigating the role of social relationships amongst patients with COPD has focussed on perception of social support and so we also focussed our review on this variable. However, conceptual models of how social networks impact health incorporate other “upstream” factors, such as the size and structure of the social network and the characteristics of network ties such as frequency of contact, reciprocity, duration and intimacy (Citation10). Revealing these upstream factors could enable a more comprehensive understanding of the pathways by which health outcomes are impacted and opportunities for intervention. These upstream factors such as network size, range, density, boundedness, reachability and the characteristics of network ties are conceptualised as providing the opportunities through which downstream psychosocial (e.g., social support) and behavioural pathways influence health and wellbeing outcomes (Citation10). However, our understanding of the social network of individuals with COPD is limited and those studies included in this review only provided minimal information about the number of individuals in the network (its size) and outside of this no information was found about social network structures or characteristics of network ties.

A large number of studies report associations between social support and important health outcomes for COPD patients and some clear trends emerged as to where there is good consistent evidence of benefits, and where further research is needed to clarify any benefits of perceived social support. A number of validated questionnaires were used by these studies which provides some confidence in the observed outcomes, although a small number of studies relied on single item assessments of support and some used instruments developed initially for use with different patient groups (e.g., (Citation20, Citation37)). It is unclear if the same results would have been achieved given more thorough assessment and/or using generic social support instruments or instruments providing COPD specific social support assessment (Table ).

Table 6. Instruments used to assess social support and social networks

In this review, we limited inclusion of studies to those that assessed functional support which is characterised by the perception of aid and encouragement provided to the individual by their social network. It was uncommon however for the studies we identified to report which components of social support were most beneficial (emotional, instrumental, appraisal or informational), and usually just a single number was given as a total social support score. It would be useful for future studies to better delineate which aspects of social support are most beneficial as this information could support the development of interventions to enhance social support.

Social support was most clearly of benefit in the area of mental health, and in particular a consistent negative relationship is seen with depression. This is consistent with Cohen's theory that social support influences the well-being of individuals by buffering the adverse effects of stressful life events and that the perception of available social support can be a source of general positive affect as well as enhanced self-esteem and feelings of belonging and security (Citation9, Citation38). Furthermore, social support was also beneficial to a sense of self-efficacy. This is consistent with the view that social support is health promoting, because it might facilitate healthier behaviours as well as greater adherence to medical regimens.

This review began with a broad question, but following an initial inspection of the available literature focussed on quantitative studies investigating two aspects of social relationships, namely perceived social support and the available social network. A number of qualitative studies detailing the lived experience of COPD and its impact on social relationships were caught by these search terms but we were unable to effectively integrate these with the emerging quantitative findings. A separate review using appropriate methodology would be useful to expand upon this initial identification of qualitative literature using dedicated search terms and meta-synthesis of qualitative findings.

Other aspects of social relationships not assessed in the studies included in this review might also be important mediators or moderators of health outcomes for COPD patients. Psychosocial mechanisms such as social influence, social engagement, person to person contact and access to resources (such as ability to work) may also influence pathways to health outcomes (Citation10). Further upstream factors associated with the social network (mezzo level factors) still need to be characterised and understood amongst COPD patients including the characteristics of social network ties and the structure of social networks, which provide the opportunities for social support and those other micro psychosocial mechanisms.

Further, in social network theory, the characteristics of network ties are often delineated as strong ties (spouse and family) and weak ties (friends and acquaintances) but no studies were found that explicitly attempted to evaluate the impact of weak social network ties or how those ties relate to management or health outcomes for COPD patients. Finally, these micro and mezzo level factors occur within the context of broader macrolevel social structural conditions such as culture, socioeconomic status, politics and social change, social capital and social cohesion, and it remains undetermined how these factors impact upon the social networks and availability of social support for patients with COPD.

Conclusion

There is consistent evidence of a positive benefit to mental health and sense of self-efficacy for patients with COPD who have adequate perceived social support, and there is an increasing body of evidence suggesting benefits in terms of self-care and adherence in the presence of adequate social support. However, there remains a need to identify the factors that promote and maintain social support as understanding these will aid in designing optimal interventions for patients with COPD. In particular there is a need to further understand the characteristics of social networks amongst patients with COPD and how this influences health and well-being outcomes for patients with COPD; within the broader social structural conditions in which COPD patients live and manage their illness.

Declaration of Interest Statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Rennard S, Decramer M, Calverley P, Pride N, Soriano J, Vermeire P et al. Impact of COPD in North America and Europe in 2000: Subjects’ perspective of confronting COPD international survey. Euro Respir J 2002; 20:799–805.

- Reardon JZ, Lareau S, ZuWallack R. Functional Status and Quality of Life in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Amer J Med 2006; 119(10A):S32–S7.

- Cafarella P, Effing T, Barton C, Ahmed D, Frith P. Management of depression and anxiety in COPD. Euro Respir Monogr 2013; 59:144–63.

- Putman-Casdorph H, McCrone S. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, anxeity, and depression: State of the science. Heart Lung 2009; 38(1):34–47.

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith T, Layton J. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLOS Med 2010; 7(7): doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316.

- Barth J, Schneider S, von Kanel R. Lack of social support in the etiology and the prognosis of coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 2010; 72:229–38.

- Shaya FT, Yan X, Farshid M, Barakat S, Jung M, Low S et al. Social networks in cardiovascular disease management. Expt Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2010; 10(6):701–5.

- Cohen S. Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychol 1988; 7(3):269–97.

- Cohen S, Wills T. Stress, social support and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 1985; 98(2):310–57.

- Berkman LF, Glass T. Social integration, social networks, social support and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press2000.

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman T. From social integration to health: Durkeheim in the new millenium. Soc Sci Med 2000; 51:843–57.

- Disler RT, Gallagher R, Davidson P. Factors influencing self-management in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: An integrative review. Inter J Nurs Stud 2012; 49:230–42.

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Inter J Soc Res Methodol 2005; 8(1):19–32.

- House J. Work Stress and Social Support. ReadingMA: Addison-Wesley1981.

- Umberson D, Montez J. Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav 2010; 51S:S54–S66.

- Sherbourne CD, Stewart A. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 1991; 32(6):705–14.

- Toshima MT, Blumberg E, Ries AL, Kaplan RM. Does rehabilitation reduce depression in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? J Cardiopulm Rehabil 1992; 12:261–9.

- Keele-Card G, Foxall MJ, Barron CR. Loneliness, depression, and social support of pateints with COPD and their spouses. Publ Health Nurs 1993; 10(4):245–51.

- Grodner S, Prewitt LM, Jaworski BA, Myers R, Kaplan RM, Ries AL. The impact of social support in pulmonary rehabilitation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Behav Med 1996; 18(3):139–45.

- McCathie HCF, Spence SH, Tate RL. Adjustments to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the importance of psychological factors. Euro Respir J 2002; 19:47–53.

- Kara M, Mirici A. Loneliness, depression, and social support of Turkish patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and their spouses. J Nurs Schol 2004; 36(4):331–6.

- Alexopoulos GS, Sirey JA, Raue PJ, Kanellopoulos D, Clark TE, Novitch RS. Outcomes of depressed patients undergoing inpatient pulmonary rehabilitation. Amer J Geriat Psych 2006; 14(5):466–475.

- Koenig HG. Predictors of depression outcomes in medical inpatients with chronic pulmonary disease. Amer J Geriat Psych 2006; 14(11):939–948.

- Coultas DB, Edwards DW, Barnett B, Wludyka P. Predictors of depressive symptoms in patients with COPD and health impact. J COPD 2007; 4:23–8.

- Lee H, Yoon J, Kim I, Jeong Y-H. The effects of personal resources and coping strategies on depression and anxiety in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart Lung 2013; 42:473–9.

- DiNicola G, Julian L, Gregorich SE, Blanc PD, Katz PP. The role of social support in anxiety for persons with COPD. J Psychosom Res 2013; 74(2):110–5.

- Holm KE, LaChance HR, Bowler RP, Make BJ, Wamboldt MD. Family factors are associated with psychological distress and smoking status in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Gen Hosp Psych 2010; 32:492–8.

- Medinas-Amoros M, Montano-Moreno JJ, Centeno-Flores MJ, Ferrer-Perez V, Renom-Sotorra F, Martin-Lopez B et al. Stress associated with hospitalization in patients with COPD: The role of social support and health related quality of life. Multidiscipl Respir Med 2012; 7:51.

- Lee H, Lim Y, Kim S, Park H, Ayn J, Kim Y et al. Predictors of low levels of self-efficacy among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in South Korea. Nurs Health Sci 2014; 16(1):78–83.

- Kara Kasikci M, Alberto J. Family support, perceived self-efficacy and self-care behaviour of Turkish patients with chronic obstructuve pulmonary disease. J Clin Nurs 2007; 16:1468–78.

- Bonsaksen T, Lerdal A, Fagermoen MS. Factors associated with self-efficacy in persons with chronic illness. Scandi J Psychol 2012; 53:333–9.

- Xiaolian J, Chaiwan S, Panuthai S, Yijuan C, Lei Y, Jiping L. Family support and self-care behavior of Chinese chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Nurs Health Sci 2002; 4:41–9.

- Young P, Dewse M, Fergusson W, Kolbe J. Respiratory rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: predictors of nonadherance. Eur Respir J 1999; 13:855–9.

- Arne M, Lundin F, Boman G, Janson C, Janson S, Emtner M. Factors associated with good self-rated health and quality of life in subjects with self-reported COPD. Inter J COPD 2011; 6:511–9.

- Marino P, Sirey JA, Raue PJ, Alexopoulos GS. Impact of social support and self-efficacy on functioning in depressed older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Inter J COPD 2008; 3(4):713–8.

- Keele-Card G, M.J. F, Barron CR. Lonelinessdepression and social support of patients with COPD and their spouses. Publ Health Nurs 1993; 10(4):245–51.

- Coventry PA, Gemmell I, Todd CJ. Psychosocial risk factors for hospital readmission in COPD patients on early discharge services: a cohort study. BMC Pulmon Med 2011; 11.

- Ashido S, Heaney C. Differential associations of social support and social connectedness with structural features of social networks and the health status of older adults. J Aging Health 2008; 20:872–93.

- Hesselink AE, Penninx BWJH, Schlosser MAG, Wijnhoven HAH, van der Windt DAWM, Kriegsman DMW et al. The role of coping resources and coping style in quality of life of patients with asthma or COPD. Qual Life Res 2004; 13:509–18.

- Blake RL, Vandiver T, Braun S, Bertuso D, Straub V. A randomised controlled evaluation of a psychosocial intervention in adults with chronic lung disease. Family Med 1990; 22:365–70.

- Lee RNF, Graydon JE, Ross E. Effects of psychological well-being, physical status, and social support on oxygen-dependent COPD patients’ level of functioning. Res Nurs Health 1991; 14:323–8.

- Anderson KL. The effect of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on quality of life. Res Nurs Health 1995; 18:547–56.

- Graydon JE, Ross E, Webster PM, Goldstein RS, Avendano M. Predictors of functioning of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart Lung 1995; 24(5):369–375.

- Scharloo M, Kaptein AA, Weinman J, Hazes JM, Willems LNA, Bergman W et al. Illness perceptions, coping and fundtioning in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and psoriasis. J Psychosom Res 1998; 44(5):573–85.

- Trappenburg JC, Troosters T, Spruit MA, Vandenbrouck N, Decramer M, Gosselink R. Psychosocial conditions do not affect short-term outcome of multidisciplinary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005; 86:1788.

- Mertens V-C, Bosma H, Groffen DAI, Van Eijk JTM. Good friends, high income or resilience? What matters most for elderly patients? Euro J Publ Health 2011; 22(5):666–71.

- Bonsaksen T, Haukeland-Parker S, Lerdal A, Fagermoen MS. A 1-year follow-up study exploring associations between perception of illness and health-related quality of life in persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Inter J COPD 2014; 9:41–50.

- Almagro P, Barreiro B, Echaguen Od, Quintana S, Rodriguez Carballeira M, Heredia JL et al. Risk factors for hospital readmission in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration 2006; 73:311–7.

- Chen Y, Narsavage GL. Factors related to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease readmission in Taiwan. West J Nurs Res 2006; 28:105–124.

- Mckay DA, Blake RL, Colwill J. Social supports and stress as predictors of illness. J Fam Pract 1985; 20:575–81.

- Sarason IF, Levin M, Basham R, Sarason B. Assessing social support: The social support questionnaire. J Person Soc Psychol 1983; 44:127–39.

- Revenson TA, Schiaffino K. Development of a contextual social support measure for use with arthritis populations. Annual Convention of the Arthritis Health Professions AssociationSeattleWA1990.

- Procidano ME, Heller K. Measures of perceived social support from friends and from famil: Three validation studies. Amer J Commun Psychol 1983; 11:1–24.

- Kara M, Mirici A. Loneliness, depression, and social support of Turkish patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their spouses. J Nurs Schol 2004; 36(4):331–336.

- Koenig HG, Westlund R, George L, Hughes D, Blazer D, Hybels C. Abbreviating the Duke Social Support Index for use in chronically ill elderly individuals. Psychosomatics 1993; 34(1):61–9.

- Coultas DB, Barnett B, Wludyka P. Predictors of depressive symptoms in patients with COPD and health impact. COPD 2007; 4:23–8.

- Byles J, Byrne C, Boyle M, Offord D. Ontario Child Health Study: reliability and validity of the general functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device. Fam Process 1988; 27(1):97–104.

- Newsom JT, Rook K, Nishishiba M, Sorkin D, Mahan T. Understanding the relative importance of positive and negative social exchanges: examining te specific domains and appraisals. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2005; 60(6):304–12.

- Di Nicola G, Julian L, Gregorich SE, Blanc PD, Katz PP. The role of social support in anxiety for persons with COPD. J Psychosom Res 2012; 74(2):110–115.

- Brandt PA, Weinert C. The PRQ—A social support measure. Nurs Res 1981; 30:277–80.

- Schreurs PJG, Tellegen B, Van De Willige G. Gezondeheid, stress, coping; de ontwikkeling van de Utrechtse Coping Lijst. Gedrag 1984; 12:101–17.

- Kempen G, van Eijk L. The psychometric properties of the SSL-12-I, a short scale for measuring social support in the elderly. Soc Ind Res 1995; 35:303–12.

- Berkman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M, Carney R, Catellier D, Cowan M et al. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) Randomised Trial. JAMA 2003; 289:3106–16.

- Bonsaksen T, Lerdal A, Solveig Fagermoen M. Factors associated with self-efficacy in persons with chronic illness. Scand J Psychol 2012; 53:333–9.