Abstract

Bilateral nephroblastomatosis (NB) is an uncommon renal anomaly characterized by multiple confluent nephrogenic rests scattered through both kidneys, with only a limited number of cases reported in the medical literature. Some of these children may have associated either Perlman or Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome and others do not demonstrate syndromic features.

We report a full-term boy with anteverted nose, bilateral bronchial stenosis due to lack of cartilage, bilateral obstructive renal dysplasia and NB with glomeruloid features. The infant had visceromegaly, but neither gigantism nor hemihypertrophy.

Immunohistochemistry for PAX2 (Paired box gene-2) and WT-1 (Wilms Tumor 1) were strongly positive in the areas of NB. GLEPP-1 (Glomerular Epithelial Protein) did not stain the areas of NB with a glomeruloid appearance, but was positive in the renal glomeruli as expected. We found neither associated bronchial stenosis nor the histology of NB resembling giant glomeruli in any of the reported cases of NB.

INTRODUCTION

Nephrogenic rests (NR) are defined as the presence of persistent embryonic tissue in postnatal kidney [Citation1]. They can occur in focal, multiple, or diffuse patterns within the renal parenchyma and are further defined as nephroblastomatosis (NB) when either multifocal or diffuse.

NR are found in approximately 1% of infant autopsies, however, this finding is typically absent after 4 months of age [Citation2].

There are two types of NR: Intralobar; which can occur anywhere within the lobe and perilobar; which is limited to the cortex. Neoplastic changes (e.g., Wilms tumor) are associated with both forms, however, these changes tend to occur at a younger age in the intralobar form (median age 16 months) compared to the perilobar form (median age 36 months).

In addition, intralobar NR are predominantly found in patients with Denys–Drash syndrome (ambiguous genitalia, propensity to Wilms tumors, and progressive renal failure) and in WAGR syndrome (Wilms tumor, aniridia, genital abnormalities and mental retardation).

On the other hand, perilobar NR are linked with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome [Citation3] (gigantism, macroglossia, omphalocele, ear creases, hemihypertrophy, umbilical hernia/omphalocele, and NR with increased predisposition to Wilms tumors) and Perlman syndrome [Citation4] (visceromegaly, gigantism, cryptorchidism, polyhydramnios, and characteristic faces).

When nephrogenic rests (perilobar and intralobar) are multiple and diffuse they are classified as nephroblastomatosis.

We present a case of an infant with anteverted nose, visceromegaly, bilateral bronchial stenosis, obstructive renal dysplasia, and bilateral nephroblastomatosis.

CASE REPORT

A full-term male infant was born via spontaneous vaginal delivery at 40 weeks. Prenatal ultrasound at 28 weeks of gestational age had revealed oligohydramnios, a prominent cerebral third ventricle, missing vertebrae, a hypoplastic thorax, and dysplastic kidneys. The mother, who was a healthy 23-year-old G1P0, had declined amniocentesis.

At birth, the baby weighed 3355 grams (45th percentile), Apgar scores were 6, 7, and 7 (at 1, 5, and 10 min, respectively), and he was apneic and cyanotic with severe respiratory failure. He was resuscitated, intubated, and transferred to the NICU for further care. His hospital course was characterized by respiratory insufficiency requiring permanent ventilator support due to tracheal and bilateral main stem bronchial obstruction, with an associated left hypoplastic lung. At 3 months of age, he underwent Nissen fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and 1 month later aortopexy was performed to attempt correction of bronchial obstruction secondary to a prominent aortic arch. However, his respiratory condition showed no improvement.

The infant's condition continued to decline over the course of his hospitalization. He developed multiple urinary tract infections and his renal function progressively deteriorated. It also became difficult to ventilate him due to the combination of severe bronchial stenosis and pulmonary hypoplasia.

Ultimately, the neonatologists had a meeting with his parents to explain the poor prognosis and together they decided not to escalate care any further. The infant expired at five months of age. Permission was granted for autopsy.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Representative sections from all organs were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours at room temperature and embedded in paraffin for routine histologic processing. Special attention was given to the renal sections that were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson trichrome, Jones Methenamine Silver (JMS), and Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS).

Immunohistochemical studies of paraffin-embedded tissue was also performed with antibodies against PAX2 (paired box gene-2), (from Zymed Laboratories, Inc, South San Francisco, CA), at a dilution of 1:100, WT-1 (Wilms tumor-1), (from DAKO, Carpinteria, California), at a dilution of ready to use, and GLEPP (glomerular epithelial protein), (from AbCam), at a dilution of 1:100. Positive and negative controls were run in parallel.

AUTOPSY FINDINGS

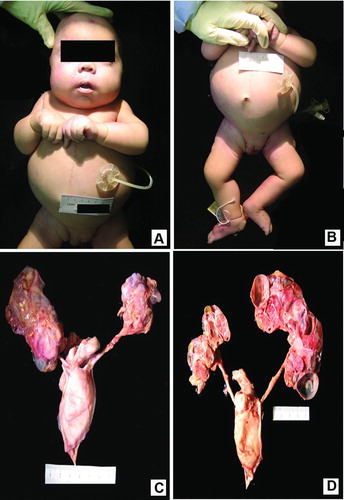

Multiple significant findings were identified on external examination. The body weighed 5443 grams (< 3rd percentile) and measured 30.5 cm from crown to rump and 24 cm from rump to heel. The cephalic circumference was 39.5 cm, chest circumference was 38.5 cm, abdominal circumference was 43 cm, and right foot length was 8.3 cm. There was moderate cyanosis and he had a small and anteverted nose and a slightly long philtrum (Figure ). The head was otherwise symmetrical with normally formed and positioned ears and patent external auditory canals. He had a hypoplastic chest, distended abdomen (Figure ), and undescended testes. Pertinent negative findings also included the lack of macroglossia and hemihypertrophy.

Figure 1. Composite macroscopic views of body and genito-urinary system: A. Frontal view shows small and anteverted nose, contracted elbows, and broad hands. The vertical, midline scar extending from chest to abdomen is secondary to aortopexy. There is a gastrostomy tube in place. B. Shows distended abdomen, hypoplastic chest, undescended testes, and bilateral talus deformity. C. Dissected kidneys, ureters, and urinary bladder in anatomic position. Note multicystic and dysplastic kidney with intermixed diffuse nodular parenchyma. The urinary bladder is enlarged as seen in obstructive renal dysplasia; however, the ureters are not distended. D. Posterior view of longitudinal section of the kidneys shows scattered multicystic renal parenchyma with lack of normal cortico-medullary demarcation, mixed with solid, nodular areas.

Additional significant findings were identified on internal examination. Within the cardiovascular system there was cardiomegaly with a weight of 44 grams (normal: 29) and an atrial septal defect (0.4 cm in diameter). The respiratory system demonstrated bilateral tracheo-bronchial mucus plugs, stenosis of right middle bronchus, and atresia of right middle, right upper, and left upper bronchi. The right lung was 62 grams (normal: 38) and the left was 56 grams (normal: 35). Both had a normal number of fissures and lobes. Except for the Nissen fundoplication and the gastrostomy tube, the gastrointestinal system was unremarkable. The liver was enlarged and weighed 420 grams (normal: 188) and the surface was red brown and smooth.

The kidneys were multicystic and dysplastic with attenuation of their reniform shape. The left kidney was 19 grams (normal: 24) and the right kidney was 33 grams (normal: 25). (Figure ) On cut section, there was loss of cortico-medullary demarcation and there were several cysts scattered through the parenchyma, but the rest of the tissue was solid (Figure ). Both ureters drained into an enlarged bladder with stenosis of the bladder outlet. The spleen was also enlarged weighing 25 grams (normal: 16) with a smooth, red-gray surface. The thymus was involuted. The adrenal glands were of normal size and shape and the pancreas was normal.

Microscopic examination showed atelectasis of both lungs. Cross sections through the bronchi demonstrated almost complete lack of cartilage that could explain the persistent bronchial stenosis. The renal parenchyma was abnormally arranged and contained multiple large nephrogenic rests, which comprised primitive renal blasteme. The majority of them contained a peripheral space resembling large glomeruli (Figure ). Immunohistochemistry for PAX2 and WT-1 were strongly positive in the areas of nephroblastomatosis (Figure and C). GLEPP-1 was also used to investigate the NR with a glomeruloid appearance. This stain was negative in the nephroblastomatosis and positive in the renal glomeruli (Figure ).

Figure 2. Composite photomicrograph of renal parenchyma: A. Hematoxylin-eosin [H&E] stain with 40 X-lens shows clusters of highly cellular sheets of primitive small blue cells with scant cytoplasm, representing the blastema component of NB that is surrounded by few epithelial tubules and fibrous stroma. B. Immunohistochemistry stain using anti PAX2 antibody (20-X lens) is immune-positive in the areas of primitive renal blastema with glomeruloid features. C. Representative immunohistochemistry image using anti WT-1 antibody. (20 X-lens). The areas of NB are strongly immunoreactive for WT-1. D. Immunostain using anti GLEPP-1 (glomerular epithelial protein) antibody (20 X-lens). Note that mature renal glomeruli stained positive, while the blastema component is negative. 103 × 77 mm (300 × 300 DPI).

![Figure 2. Composite photomicrograph of renal parenchyma: A. Hematoxylin-eosin [H&E] stain with 40 X-lens shows clusters of highly cellular sheets of primitive small blue cells with scant cytoplasm, representing the blastema component of NB that is surrounded by few epithelial tubules and fibrous stroma. B. Immunohistochemistry stain using anti PAX2 antibody (20-X lens) is immune-positive in the areas of primitive renal blastema with glomeruloid features. C. Representative immunohistochemistry image using anti WT-1 antibody. (20 X-lens). The areas of NB are strongly immunoreactive for WT-1. D. Immunostain using anti GLEPP-1 (glomerular epithelial protein) antibody (20 X-lens). Note that mature renal glomeruli stained positive, while the blastema component is negative. 103 × 77 mm (300 × 300 DPI).](/cms/asset/b6eca4bc-9756-454e-ac69-775f48c1d9c3/ipdp_a_1014952_f0002_c.jpg)

DISCUSSION

Bilateral nephroblastomatosis (NB) is an uncommon renal anomaly, with only a limited number of cases reported in the medical literature. NB was first described in a preterm neonate by Drs. Hou and Holman in 1961. That girl survived only 13 hours and had symmetric, massively enlarged, solid kidneys [Citation5]. They concluded that ‘In view of the many features resembling nephroblastomas, we think the term “nephroblastomatosis” would be most appropriate.’ Nine years later, Liban et al. published a series on four siblings with nephroblastomatosis, whose parents were first cousins [Citation6]. Then in 1973, Perlman and Kosenitzky published a case report on an additional sibling from the same family [Citation7]. That infant had enophthalmos, small nose with a depressed bridge, everted upper lip, and low-set ears. The autopsy revealed generalized visceromegaly, islet cell hyperplasia and hypertrophy, and nephroblastomatosis. Several small series and single case reports of NB detected at autopsy have followed over the course of the next three decades [Citation8–11]. A series by De Chadarevian et al. described four children with nephromegaly detected on physical examination and confirmed by imaging. Histology showed NB and all of the children were treated with chemotherapy for Wilms tumor. One Japanese child from consanguineous parents died shortly after birth due to respiratory insufficiency and the autopsy revealed bilateral and diffuse NB [Citation9]. We published two case reports with Dr. Bruce Beckwith on patients with bilateral NB in 1994 and 1996, respectively. The patients were unrelated and the morphology of NB was completely different in each. The case published in 1994 contained a more classical renal blastemal comprising confluent perilobar nephrogenic rests with an associated renal dysplasia. On the other hand, the 1996 case had tubular differentiation resembling the epithelial component of some Wilms tumors [Citation10, 11]. Lastly, a more recent report on two siblings with bilateral nephromegaly and autopsy proven universal NB, suggested an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance [Citation12].

Our current patient had visceromegaly without gigantism or any of the other features of Beckwith–Wiedemann or Perlman syndrome. He had an associated obstructive renal dysplasia and extensive bronchial stenosis due to a congenital lack of cartilage. The latter feature, to the best of our knowledge, has not been reported in any other patients with universal NB. Moreover, the histology of his NB differed from that of all the other reported cases, as the nodules of immature blue cells had a glomeruloid appearance that in our opinion is unique to this patient. The areas of NB were immune-positive for the transcription factor PAX2 and WT-1. These two markers have been proven to be upregulated in nephrogenesis and in early epithelial structures derived from mesenchyme [Citation13]. WT-1 can be positive in Wilms tumors, even with tubulopapillary morphology [Citation14]. Since the infant survived 5 months and the NB was an autopsy finding, he was not treated by chemotherapy and we can assure the readers that up to 5 months of age, he had not developed a Wilms tumor; therefore, the malignant potential in our patient seems to be low.

An intriguing possibility would be to study Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) signaling since it has been associated with urethral obstruction. Shh mediates epithelial to mesenchymal communication and induces renal fibrosis that is associated with renal dysplasia [15]. On the other hand, Sox9 by Shh is also required for proper development of tracheal cartilage [16].

Our intention is to report this unusual case and raise awareness among pathologists about the possibility of congenital absence of tracheal cartilage in neonates with renal dysplasia and NB. This may be an important finding in infants that did not survive long enough to produce clinical symptoms because of severe pulmonary hypoplasia due to oligohydramnios and a careful autopsy could confirm. The majority of these cases are autosomal recessive; therefore, the parents should be counseled about the 25% chance of recurrence.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

REFERENCES

- Perlman EJ. Renal tumors. Chapter 27. In: Potter's Pathology of Fetus and Infant. 2nd ed. Gilbert-Barness E, ed. New York, NY: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

- Lonergan GJ, Martinez-Leon MI, Agrons GA, et al. Nephrogenic rests, nephroblastomatosis, and associated lesions of the kidneys. Radiographics 1998;18:947–968.

- Elliott M, Bayly R, Cole T, et al. Clinical features and natural history of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome: presentation of 74 new cases. Clin Genet 1994;46:168–174.

- Perlman M, Levin M, Wittels B. Syndrome of fetal gigantism, renal hamartomas, and nephroblastomatosis with Wilms’ tumor. Cancer 1975;35:1212–1217.

- Hou LT, Holman RL. Bilateral nephroblastomatosis in a premature infant. J Pathol Bacteriol 1961;82:249–255.

- Liban E, Kozenitzky IL. Metanephric hamartomas and nephroblastomatosis in siblings. Cancer 1970;25:885–888.

- Perlman M, Goldberg GM, Bar-Ziv J, Danovitch G. Renal hamartomas and nephroblastomatosis with fetal gigantism: A familial syndrome. J Pediatr 1973;83:414–418.

- De Chadarevian JP, Fletcher BD, Chatten J, Rabinovitch HH. Massive infantile nephroblastomatosis: a clinical, radiological, and pathologic analysis of four cases. Cancer 1977;39:2294–2305.

- Murata T, Yoshida T, Takanari H, et al. Bilateral diffuse nephroblastomatosis, pancortical type. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1989;113:729–734.

- Regalado JJ, Rodriguez MM, Bruce JH, Beckwith JB. Bilateral hyperplastic nephromegaly, nephroblastomatosis, and renal dysplasia in a newborn: a variety of universal nephroblastomatosis. Pediatr Pathol 1994;14:421–432.

- Regalado JJ, Rodriguez MM, Beckwith JB. Multinodular hyperplastic pannephric nephroblastomatosis with tubular differentiation: a new morphologic variant. Pediatr Pathol 16:961–972.

- Katzman PJ, Arnold GL, Lagoe EC, Huff V. Universal nephroblastomatosis with bilateral hyperplastic nephromegaly in siblings. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2009;12:47–52.

- Rojas CP, Urbiztondo AK, Bruce JB, Rodriguez MM. Comparative immunohistochemical study of multicystic dysplastic kidneys with and without obstruction. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 2011;30:209–219.

- Chen L, Deng FM, Melamed J, Zhou M. Differential diagnosis of renal tumors with tubulopapillary architecture in children and young adults: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Clin Exp Urol 2014;2:266–272.

- Ding H, Zhou D, Hao S, Zhou L, He W, Nie J, Hou FF, Liu Y. Sonic Hedgehog signaling mediates epithelial-mesenchymal communication and promotes renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012;23:801–813.

- Park J, Zhang JJR, Moro A, Kushida M, Wegner M, Kim PCW. Regulation of Sox9 by Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) is essential for patterning and formation of tracheal cartilage. Dev Dynam 2010;239:514–526.