Abstract

Limb body wall complex (LBWC) is characterized by multiple severe congenital malformations including an abdominal and/or thoracic wall defect covered by amnion, a short or absent umbilical cord with the placenta almost attached to the anterior fetal wall, intestinal malrotation, scoliosis, and lower extremity anomalies. There is no consensus about the etiology of LBWC and many cases with abnormal facial cleft do not meet the requirements for the true complex. We describe a series of four patients with LBWC and other malformations in an attempt to explain their etiology. There are several reports of fetuses with LBWC and absent gallbladder and one of our patients also had polysplenia. Absent gallbladder and polysplenia are associated with laterality genes including HOX, bFGF, transforming growth factor beta/activins/BMP4, WNT 1–8, and SHH. We postulate that this severe malformation may be due to abnormal genes involved in laterality and caudal development.

INTRODUCTION

Limb-body wall complex (LBWC) is a rare congenital disorder characterized by anomalies that are almost invariably incompatible with life. The phenotype is highly variable and so far has been defined by the presence of exencephaly or encephalocele with facial clefts, thoracoschisis and/or abdominoschisis, and limb defects [ Citation1]. It has been recognized since Hippocrates that fetal mechanical deformities can be due to a small uterine cavity [ Citation2]. However, we consider that either an absent or a short-umbilical cord wrapped around the extra embryonic coelom (EECC) is a required condition to qualify for LBWC.

Bugge et al. have already mentioned that a short umbilical cord and kyphoscoliosis are almost invariably present in LBWC [ Citation3]. We believe that the short umbilical cord could be attributed to fetal hypomotility, but on the other hand, a short umbilical cord could make the fetus pull the abdominal wall in order to move within the amniotic sac and therefore facilitate the body wall defect (abdominoschisis and /or thoracoschisis). Additional anomalies of external and internal organs including limb and spine defects have been described [ Citation4]. The etiology of LBWC is not well understood. Multiple hypotheses have been proposed in an attempt to provide a conclusive explanation. We believe that including within the LBWC cases with exencephaly, encephalocele and facial clefts without short umbilical cord wrapped around the amnion can be misleading as they seem to be a different defect. This wrong classification could add to the complexity of trying to determine the etiology of these defects.

We report four cases of LBWC with short umbilical cord wrapped around the extra-embryonic coelom, thoracic and/or abdominal wall defects, limb defects, and vertebral malformations, but none of them had facial clefts and each case is characterized by a distinct combination of additional anomalies.

METHODS

Surgical Pathology files at Jackson Memorial Hospital were searched for diagnosis of limb body wall defects for the 12-year period from January 1st, 2003 to December 31st, 2014. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was previously obtained. Data were gathered in a data sheet including gestational age at diagnosis and at delivery, birth weight, body measurements, type of body wall defect (abdominal, thoracic or thoraco-abdominal), umbilical cord anomalies, presence of diaphragmatic, intestinal or limb defects, or any other anomalies. Maternal clinical histories and color photographs were reviewed and conventional fetal radiological studies were examined by a Pediatric Radiologist (GS). The information obtained was tabulated, analyzed, and conclusions were drawn.

Table 1. Maternal and fetal information for our four patients.

RESULTS

Patient 1

This patient was delivered at 19 weeks to a 34-year-old Hispanic mother (Table 1). The mother was G5 P3013. She had had three spontaneous vaginal deliveries and one termination of pregnancy. Her gynecological history was unremarkable (menarche at age 14 years with cycles every month and duration of 4 to 5 days, no sexually transmitted diseases, no pelvic inflammatory disease, no oral contraceptive pills and no intrauterine device use).

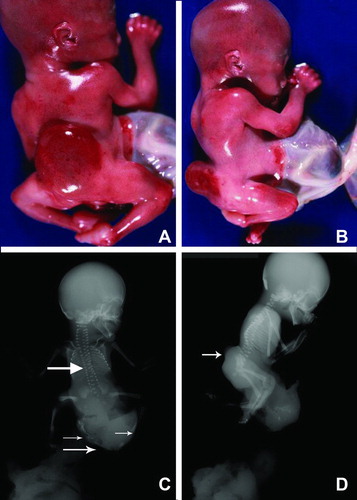

Figure 1. (A) Posterior view of Patient 1 showing fetus with sacrolumbar myelomeningocele, and contracted lower extremities. (B) Lateral fetal view depicts the attached amnion covering omphalocele with a short umbilical cord wrapped around the amnion covering the abdominal wall defect. The fetus also has bilateral flexion contracture deformity of lower extremities. (C) Post-mortem antero-posterior x-ray showing segmentation anomalies of the thoracic vertebrae (thick arrow), omphalocele (thin arrow) and meconium peritonitis (small thin arrows). (D) Post-mortem lateral x-ray showing lumbosacral myelomeningocele (arrow).

Figure 2. (A) Gross picture of Patient 1 showing fetus with attached cord and placenta. (B) Closer view of short umbilical cord covered with amnion. Notice a large interface of abdominal skin with omphalocele sac.

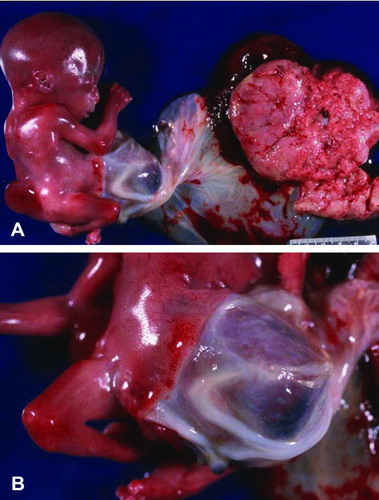

Figure 3. Gross photograph of Patient 2 showing fetus with a right antero-lateral body wall thoracoabdominoschisis covered by amnion. The right upper extremity is missing, the umbilical cord is short and the lower extremities are slightly contracted.

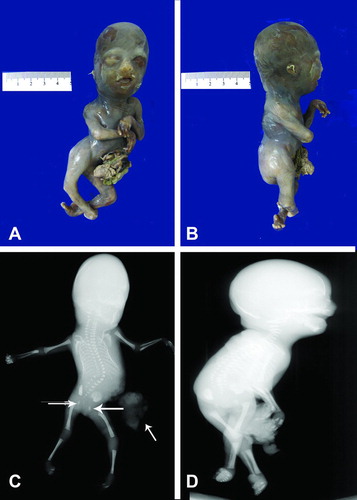

Figure 4. (A–B). Gross picture of macerated fetus after formalin fixation showing club-feet deformity and an abdominal wall defect. The lower extremities are contracted. (C–D) Post-mortem antero-posterior and lateral x-rays showing severe levoscoliosis, widely separated ischial ossification centers (larger arrows), and external protrusion of abdominal contents (smaller arrow), and club foot deformity.

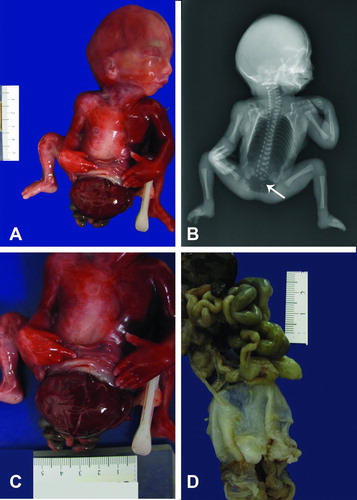

Figure 5. (A) Gross photograph of fetus with no external genitalia and omphalocele sac involving abdomen and pelvis. Notice flexion deformity of both lower extremities. (B) Post-mortem antero-posterior x-ray showing a large lucency occupuing the chest and abdomen consistent with post-mortem air, there are vertebral body segmentation anomalies and hypoplastic sacrum (arrow). (C) Photograph depicts a closer view of extracorporeal organs. (D) Gross picture of formalin fixed organ block of Patient 4. The lower portion demonstrates the omphalocele sac still attached to abdomino-pelvic organs.

Prenatal ultrasound showed a fetus with multiple anomalies and the mother elected termination of pregnancy with misoprostol. External examination revealed a nonmacerated fetus whose sex could not be determined initially due to absence of external genitalia, weighing 245 grams, and with a crown-heel length of 19.0 cm and foot length of 2.2 cm (Figure ). The fetus had a large defect in the anterior abdomen covered by the amnion, measuring 6.0 × 6.0 × 4.5 cm containing part of the liver and gastrointestinal tract and a very short umbilical cord partially wrapped with the amnion and the placenta still attached to the fetus ( ). The abdominal wall defect was classified as an omphalocele. Lumbar scoliosis and a sacrolumbar myelomeningocele were noted. The anus was imperforate and there was bilateral flexion contracture deformity of the lower extremities.

Internal examination revealed the heart with normal anatomy and position, but with a persistent left superior vena cava draining to the right atrium via the coronary sinus. The lobation of both lungs was normal. An enlarged liver with absent gallbladder and a posteriorly located extra quadratus lobe as well as left-sided polysplenia were identified. There was intestinal malrotation with a blind-ended small bowel. The right and left kidneys and adrenals were normal, but the urinary bladder was distended. The testicles and a small phallus with erectile tissue were located in the pelvis and fetal chromosomal analysis demonstrated a normal male karyotype (46, XY.)

Postmortem X-rays of the body - antero-posterior (AP) (Figure 1C) and lateral views (1D) demonstrate a small, completely opacified chest. There was a small lucency in the right chest which may have been postmortem in nature. A large lower abdominal body wall defect with soft tissue protruding externally was noted, consistent with an omphalocele (arrow). The omphalocele demonstrated were multiple underlying calcifications, which were likely due to prior bowel perforation and subsequent meconium peritonitis (Figure 1C, small thin arrows). Multiple segmentation anomalies of the vertebrae are noted in the thoracic spine (Figure 1C, larger arrow). Hypoplasia of the sacrum was noted.

There was lumbosacral spinal dysraphism with soft tissue noted to project dorsally, consistent with a lumbosacral myelomeningocele (Figure 1D, arrow). The iliac bones and the ischial ossification centers were widely separated. There were flexion deformities of both feet. The skull is normally ossified. The fetus was delivered with the placenta still attached to a short umbilical cord wrapped around the amniotic sac attached to abdominal skin (Figure 2A&B).

Patient 2

This fetus was delivered at 18 weeks to a 36-year-old Hispanic mother, G2P1001 (the previous full-term baby had been born by a cesarean section). The mother denied any drug or alcohol abuse. Her menarche was at age 13, regular and lasting for 3 days. Vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain in the first trimester had prompted a prenatal ultrasound which provided evidence for a twin gestation with a spontaneous abortion of twin A at 14 weeks gestational age. The second fetal ultrasound revealed the co-twin with multiple congenital anomalies including: a large omphalocele, kyphoscoliosis, an abnormal cardiac four chamber view, and absent external genitalia.

Due to increasing vaginal bleeding and maternal abdominal pain, labor was induced at 18 weeks of gestation and resulted in a nonmacerated fetus of 191 grams (Figure ), crown-heel length of 16.8 cm, cephalic circumference of 14.6 cm and foot length of 2.6 cm. There was a right antero-lateral body wall defect with thoraco abdominoschisis covered by amnion containing part of the umbilical cord, liver and intestine. The entire right upper extremity was absent and there were flexion contracture deformities of both lower extremities. Facial features included hypertelorism, low-set ears, and broad nasal bridge. The anus was imperforate.

Internal examination revealed bilateral pulmonary hypoplasia, more severe in the right lung and severe scoliosis with right concavity. Additional findings included a large right-sided diaphragmatic hernia, with the right kidney, adrenal, and testes inside the thoracic cavity. No radiological studies were available for this fetus.

Patient 3

This patient was delivered at 18 weeks to a 31-year-old primigravida Hispanic mother, who had presented with amenorrhea. The mother denied any drug or alcohol use. An anatomy screen ultrasound at 18 weeks of gestation demonstrated a large omphalocele containing liver and stomach, a partially missing anterior thoracic wall, bilateral club feet, clenched hands and severe kyphoscoliosis.

The mother was advised to have an amniocentesis, but refused and opted for termination of pregnancy. Labor was induced at 18 weeks gestational age and resulted in a severely macerated female fetus weighing 200 grams (Figure ), crown-heel length of 21.5 cm, and foot length of 2.0 cm. An anterior abdominal wall defect to the left of the umbilical cord was noted, with stomach, liver, spleen, small, and large intestines. The fingers displayed axial deviation with camptodactyly (flexion of one or more fingers), and there was bilateral talipes calcaneovarus. Severe left sided scoliosis was also present. The eyes were normally placed and the ears were low-set. The anus was patent.

On internal examination, the diaphragm was intact. The right and left lungs showed areas of hemorrhage in the lower lobes, the heart was normally located but had extensive maceration. The brain showed severe autolysis and the spinal cord was also extremely macerated. On conventional radiological study, there was evidence of marked levoscoliosis of the thoracolumbar spine without any congenital vertebral body anomalies. The ischial ossification centers appeared to be widely separated. Bilateral club foot deformity and flexed hands were confirmed. Normal ossification of the skull was evident.

Post mortem X-rays of the body—AP (Figure 4C) and lateral (Figure 4D) views demonstrated marked levoscoliosis of the thoracolumbar spine without any congenital vertebral body anomalies. Club foot deformities were noted bilaterally. There was an abdominal body wall defect with protrusion of bowel contents externally (Figure 4C, smaller arrows). The ischial ossification centers were widely separated (Figure 4C, larger arrows). Hands were flexed bilaterally. The upper and lower extremity bones were otherwise unremarkable. Normal ossification of the skull was noted.

Patient 4

This patient was delivered at 19 weeks to a 30-year-old primigravida Hispanic mother, who denied any drug or alcohol use. An ultrasound at 13 weeks gestational age demonstrated abnormal findings including large fetal omphalocele with extracorporeal liver and intestinal loops as well as a small cystic hygroma. The mother refused chorionic villus sampling, amniocentesis and genetic testing, but agreed to cell-free DNA testing which showed normal results.

Following counseling on the guarded prognosis given the constellation of findings, the mother was given the options of pregnancy continuation with antenatal testing, the potential need for a cesarean section, and the possibility of termination of pregnancy. After deliberation, she opted for termination of pregnancy. Labor was induced at 19 weeks gestational age and resulted in a nonmacerated fetus weighing 238 g (Figure 5), crown-heel length of 20.9 cm, cephalic circumference of 15 cm, and foot length of 3.0 cm. There were no external genitalia. The fetus had a defect in the abdominal wall and pelvis with extracorporeal stomach, liver, pancreas, spleen and intestines covered by a thin, ruptured, translucent membrane consistent with an omphalocele sac measuring 10.0 × 8.0 cm with 6.5 cm of umbilical cord running through it. Facial features included fused eyes, micrognathia, and a redundancy of the nuchal folds with minimal fluid accumulation. The external genitalia were absent and the anus was imperforate. The hips were in an abducted position and the knees were in flexed position at a 90° angle. No other gross limb defects were identified.

On internal examination, the heart, lungs and great vessels were in normal position. The diaphragm was absent. The right adrenal was not attached to the right kidney and the left adrenal was located medial to the left kidney. The ureter was attached to a tubular structure, but no definitive urinary bladder or internal genitalia were seen. A blind-ended cloaca was dissected.

A post mortem AP X-ray of the body (Figure 5B) demonstrated a large lucency occupying the entire chest and abdominal cavities consistent with post mortem air. Abdominal contents were not seen which was consistent with the clinical history. Vertebral body segmentation anomalies were noted at multiple levels throughout the spine most prominent in the sacrum (arrow). Widening of the iliac bones and the ischial ossification centers was noted. There was bilateral flexion deformity of the hands. The upper and lower extremity bones were otherwise unremarkable. The skull was normally ossified. Table 1 summarizes the clinical information and pathology of our four patients.

DISCUSSION

Multiple hypotheses have attempted to elucidate the etiology of LBWC, but consensus has been limited. The three mechanisms that have been proposed are: early amnion rupture, embryonic circulatory failure, and embryonic dysgenesis [ Citation5]. These authors emphasized cases with a short umbilical cord running at the margin of a membranous sac that covered the gut and connected via amnion to the placenta. None of our four patients had facial anomalies such as clefts, but all of them had limb defects including flexion deformities of both lower extremities. Amniotic bands were also not found.

Patient 2 (resulting from a diamniotic–dichorionic twin pregnancy with earlier abortion of twin A) also had the right upper extremity missing, and patient 3 developed axial deviation of hands and feet, camptylodactyly and talipes deformities of both feet. All our patients had a short umbilical cord wrapped around the amnion and two of the four also had a single umbilical artery. There was no sex predilection as they were two males and two females.

Van Allen et al. proposed that the diagnosis of LBWC should be based on the presence of at least two of three anomalies including exencephaly or encephalocele with facial clefts, thoraco and/or abdominoschisis, and limb defects [ Citation1] and postulated that vascular disruption occurring at 4–6 weeks gestational age is the basis for LBWC. The authors discussed the systemic vascular phenomenon as predominantly affecting perfusion of blood to a specific body quadrant, arguing against a disruptive role for amniotic bands because they were not observed to correlate with anomalies in 40% of their cases. However, no occluded vessel has ever been documented in these patients. Amnion connections were considered to be secondary to adhesions between necrotic fetal tissue and the amnion. It is our impression that patients with facial clefts, anterior encephalocele, and partial or complete limb amputations should not be classified together with the true LBWC as the etiology may be totally different from that of patients with short umbilical cord wrapped with the amniotic sac.

Pagon et al. [ Citation6] subdivided their cases into three groups, specifically thoracogastroschisis, midline abdominal defects, and lateral abdominal wall defects, reporting upper and lower limb anomalies, external genital anomalies and imperforate anus. On the other hand, Russo et al. [ Citation7] referred to LBWC as limb body wall disease (LBWD) and subdivided it into two types, with Type 1 defined as having exencephaly/encephalocele, facial clefts, amniotic bands and broad amnion/cranial adhesions and Type 2 as lacking craniofacial findings, bands or adhesions and having a high rate of urogenital, internal female genital, anal, cloacal and lumbosacral anomalies, a persistent EECC and intact amnion. Hartwig et al. [ Citation8] studied four fetuses with LBWC, but they made it synonymous with amniotic band syndrome, which in our viewpoint is incorrect.

Craven et al. from University of Utah [ Citation9] appreciated the existence of subtypes of LBWC and realized that a focus on cases with similar manifestations would help in identification of the etiology. This group selected cases with abdominoschisis associated with a broad band of attachment of amnion to the skin of the abdominal wall defect, umbilical cord agenesis with the umbilical vessels running through the membrane, and a limb defect of any type in order to focus on a possible malformation rather than a disruption. The authors reasoned that the abdominal wall defect was due to failure of abdominal wall closure caused by two possible variations of amnion growth.

More recently, Hunter et al. [ Citation10] proposed that a primary defect or deficiency of the ectoderm of the embryonic disc can explain most of the key malformations observed in LBWC, with the affected area and extent depending on the location and severity of the ectoderm defect. This hypothesis is similar to that of Hartwig et al. [ Citation8], but aims at a more detailed and precise explanation of the pathogenesis; it also attributes most aspects of LBWC to the ectoderm itself rather than ectodermal placodes and provides detailed explanations for the manifold limb anomalies observed in individual cases.

We are reporting four cases of LBWC that emphasize its great degree of phenotypic variability. All have thoracoabdominal or abdominal wall defects with varying degrees of organ contents and short umbilical cords for gestational age (8.7 cm ± 2.3 cm). The short umbilical cords in our patients may help explain at least some of the limb deformities found, such as the flexion contracture deformities. One can imagine that an umbilical cord shorter than normal for gestational age would force fetal extremities into unphysiological positions, resulting in deformities. Of note, none of our patients had facial clefts or skull deformities. None of the mothers had either a previous or recurrent malformed fetus.

Our patient 1 had absent gallbladder, left-sided polysplenia, hypoplastic sacrum, and a sacrolumbar myelomeningocele. The only cardiovascular anomaly observed was a persistent left superior vena cava. These malformations do not seem to be related to amniotic bands or embryonic circulatory failure. Absent gallbladder was reported by Van Allen et al in several of their cases [ Citation1]. We have not found any report of patients with polysplenia in any of the previously published cases; however, our patient 1 had a myelomeningocele and hypoplastic, contracted lower extremities as seen in caudal dysplasia and we previously reported one patient with caudal dysplasia that also had polysplenia as part of a series of patients with either caudal dysplasia or sirenomelia [ Citation11].

Among the several structural anomalies found in our small series and previously reported cases that cannot be explained by either amniotic disruption sequence or mechanical deformities are: absent or short umbilical cord, wrapped around the amnion, meningocele, hypoplastic sacrum, polysplenia, absent gallbladder, cloacal anomalies with imperforate anus, and congenital heart disease. Factors that may play a role include teratogens such as maternal alcohol consumption or smoking. A series of cases from Australia reported history of cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use [ Citation12]. However, these authors included patients with exencephaly and facial clefts without abdominal or thoracic wall defects. Many of these women had a history of a previous spontaneous abortion. The group from Australia reported one mother who delivered two consecutive fetuses with LBWC. Nevertheless, the majority of reported cases did not have a recurrence of this type of anomaly. We did not find evidence either in our patients or the reviewed medical literature of any consistent medication, contraceptive method or any other factor that may have played a role in the development of LBWC.

Another interesting feature that to the best of our knowledge has not been explored is the absent gallbladder, a feature that can be found in polysplenia [ Citation13]. We examined a fetus with LBWC in this series that also had polysplenia and absent gallbladder.

Several genes have been implicated in laterality development including HOX genes, βFGF (basic fibroblast growth factor), transforming growth factor β/activins/BMP4 (bone morphogenetic protein 4); WNT 1–8, and SHH (Sonic Hedgehog) [ Citation14]. The medical literature tends to deny a genetic origin of LBWC based on the fact that there are almost no recurrences in siblings. However, the majority of these fetuses are either aborted or die shortly after birth of respiratory insufficiency and a de novo mutation will only be present in the patient and his/her children if reproduction were an option. The majority of these patients have imperforate anus and urinary bladder anomalies. We have found an article describing the relationship between ZIC3 gene, heterotaxy, and VACTERL association [ Citation15]. The patient was the only affected family member.

Other genes that are involved in caudal neural tube development and cloacal anomalies are Cdx/Hox genes and Wnt3a that have been studied in Drosophila [ Citation16]. We postulate these genes may also be associated with LBWC development.

When one of these abnormal fetuses is detected by ultrasound, the mothers can be counseled about the very low risk of recurrence, and since the severity of malformations is almost always incompatible with life, elective termination of pregnancy can be suggested to avoid further suffering of the neonate and family. The degree of definition attained by fetal ultrasound nowadays is such that an early diagnosis can be made in the first trimester [ Citation17] and abortion can be induced with less morbidity to the mother.

We believe that there is a subset of fetuses with the true LBWC that may have undergone a de novo mutation and only a larger series in which molecular studies are performed will lead to enough informative cases to prove our theory of a genetic mutation that cannot be passed to the following generation because the severity of congenital anomalies is such that either the pregnancies are terminated or the neonates die shortly after birth of respiratory insufficiency.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

REFERENCES

- Van Allen MI, Curry C, Walden CE, Gallagher L, James F. Reynolds: Limb body wall complex: I. Pathogenesis. Am J Med Genet 1987;28:529–548.

- Miller ME. Structural defects as a consequence of early intrauterine constraint: Limb deficiency, polydactyly, and body wall defect. Semin Perinatol 1983;7:274–277.

- Bugge M. Body stalk anomaly in Denmark during 20 years (1970–1989). Am J Med Genet A 2012;158A:1702.

- Van Allen MI, Curry C, Walden CE, Gallagher L, James F. Reynolds: Limb body wall complex: II. Pathogenesis. Am J Med Genet 1987;28:549–565.

- Colpaert C, Bogers J, Hertveldt K, Loquet P, Dumon J, Willems P. Limb body wall complex: 4 new cases illustrating the importance of examining the cord and placenta. Pathol Res Pract 2000;196:783–790.

- Pagon RA, Stephens TD, McGillivray BC, Siebert JR, Wright VJ, Hsu LL, Poland BJ, Emanuel I, Hall JG. Body wall defects with reduction limb anomalies: A report of fifteen cases. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser 1979;15(5A):171–185.

- Russo R, D'Armiento M, Angrisani P, Vecchione R. Limb body wall complex: A critical review and a nosological proposal. Am J Med Genet 1993;47:893–900.

- Hartwig NG, Vermeij-Keers C, De Vries HE, Kagie M, Kragt H. Limb Body wall malformation complex: An embryologic etiology? Hum Pathol 1989;20:1071–1077.

- Craven CM, Carey JC, Ward K. Umbilical cord agenesis in limb body wall defect. Am J Med Genet 1997;71:97–105.

- Hunter AGW, Seaver LH, Stevenson RE. Limb—body wall defect. Is there a defensible hypothesis and can it explain all the associated anomalies? Am J Med Genet Part A 2011;155:2045–2059.

- Bruce JH, Romaguera RL, Rodriguez MM, Gonzalez-Quintero VH, Azouz EM. Caudal dysplasia syndrome and sirenomelia: are they part of the spectrum?. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 2009;28:109–131.

- Luehr B, Lipsett J, Quinlivan A. Limb-body wall complex: a case series. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2002;12:132–137.

- Meinecke P, Peper M. Intrauterine growth retardation, mild frontonasal dysplasia, phocomelic upper limbs with absent thumbs and a variety of internal malformations including choanal atresia, congenital heart defects, polysplenia, absent gallbladder as well as genitourinary anomalies. A possibly “new” MCA syndrome?. Gent Couns 1992;3:53–56.

- Gilbert-Barness E, Debich-Spicer D, Cohen MM, Opitz JM. Evidence for the “Midline” hypothesis in associated defects of laterality formation and multiple midline anomalies. Am J Med Genet 2001;101:382–387.

- Wessels MW, Kuchinka B, Heydanus R, Smit BJ, Dooijes D, de Krijger RR. Polyalanine expansion in the ZIC3 gene leading to heterotaxy with VACTERL association: a new polyalanine disorder? J Med Genet 2010;47:351–355.

- van de Ven C, Bialecka M, Neijts R, Young T, Rowland JE, Stringer EJ, van Rooijem C. Concerted involvement of Cdx/Hox genes and Wnt signaling morphogenesis of the caudal neural tube and cloacal derivatives from the posterior growth zone. Development 2011;138:3451–3462.

- Quijano P, Rey MM, Echeverry M, Axt-Fliedner R. Body stalk anomaly in a 9-week pregnancy. Case Rep Obstetr Gynecol 2014:35:7285.