Abstract

Background: This is the 27th Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' (AAPCC) National Poison Data System (NPDS). As of 1 July 2009, 60 of the nation's 60 US poison centers (PCs) uploaded case data automatically. The upload time was 19.9 [9.7, 58.7] (median [25%, 75%]) minutes, creating a near real-time national exposure and information database and surveillance system.

Methodology: We analyzed the case data tabulating specific indices from NPDS. The methodology was similar to that of previous years. Where changes were introduced, the differences are identified. Poison center cases with medical outcomes of death were evaluated by a team of 29 medical and clinical toxicologist reviewers using an ordinal scale of 1-6 to determine Relative Contribution to Fatality (RCF) of the exposure to the death.

Results: In 2009, 4,280,391 calls were captured by NPDS: 2,479,355 closed human exposures, 116,408 animal exposures, 1,677,403 information calls, 6,882 human confirmed nonexposures, and 343 animal confirmed nonexposures. The top 5 substance classes most frequently involved in all human exposures were analgesics (11.7%), cosmetics/personal care products (7.7%), household cleaning substances (7.4%), sedatives/hypnotics/antipsychotics (5.8%), and foreign bodies/toys/miscellaneous (4.3%). Analgesic exposures as a class increased the most rapidly (12,494 calls per year) over the last decade. The top 5 most common exposures in children age 5 or less were cosmetics/personal care products (13.0%), analgesics (9.7%), household cleaning substances (9.3%), foreign bodies/toys/miscellaneous (7.0%), and topical preparations (6.8%). Drug identification requests comprised 63.0% of all information calls. NPDS documented 1,544 human exposures resulting in death with 1,158 human fatalities judged related with an RCF of 1-Undoubtedly responsible, 2-Probably responsible, or 3-Contributory.

Conclusions: Unintentional and intentional exposures continue to be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the US. The near real-time, always current status of NPDS represents a national public health resource to collect and monitor US exposure cases and information calls. The continuing mission of NPDS is to provide a nationwide infrastructure for public health surveillance for all types of exposures, public health event identification, resilience response and situational awareness tracking. NPDS is a model system for the nation and global public health.

Introduction

This is the 27th Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' (AAPCC; http://www.aapcc.org) National Poison Data System (NPDS). Citation1 On 1 January 2009, Sixty-one regional Poison Centers (PCs) serving the entire population of the 50 United States, American Samoa, District of Columbia, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands submitted information and exposure case data collected during the course of providing telephonic patient tailored exposure management. On 30 June 2009, The DeVos Children's Hospital Regional Poison Center, Grand Rapids, Michigan, serving upper Michigan ceased operation. Michigan is now served by one poison center. During this transition national coverage remained seamless. Data is compiled by the American Association of Poison Control Centers' (AAPCC) National Poison Data System (NPDS). PCs place emphasis on exposure management, accurate data collection and coding, and the continuing need for poison related public and professional education. The centers' health care professionals are available free of charge to all, 24-hours a day, every day of the year. PCs respond to questions from the public, health care professionals, and public health agencies. The continuous staff dedication at the regional PCs is manifest as the number of exposure and information calls exceeds 4.2 million annually. Calls to PCs either involve an exposed human or animal (EXPOSURE CALL) or a request for information (INFORMATION CALL) with no exposed person or animal.

WARNING: Comparison of exposure or outcome data from previous AAPCC Annual Reports is problematic. In particular, the identification of fatalities (attribution of a death to the exposure) differed from pre-2006 Annual Reports (see Fatality Case Review – Methods). Poison center death cases are described as all cases resulting in death and those determined to be exposure-related fatalities. Likewise, (Exposure Cases by Generic Category) since year 2006 restricts the breakdown including deaths to single-substance cases to improve precision and avoid misinterpretation.

What's New in NPDS and the Annual Report

Several enhancements were made to the tables and figures in this 27th Annual Report. Continuing goals of the writing team have been to remove inconsistencies, improve the reader's ability to clearly understand the data, and provide additional data where appropriate. Achievement of these goals has been exemplified by the new version of that was introduced with the 2006 Annual Report and last year's corrections for clarity to the age labels in all tables (described below). The improvements made to the tables and figures are listed below:

Tables

Five new , , , , and ) have been added to provide additional information on decontamination trends, change of substance exposure rates over time, pediatric exposures, information calls, and deaths. - Decontamination Trends: Total Human and Pediatric Exposures ≤5 Years (2009) provides decontamination trends for 2009 for all exposures and pediatric exposures. , and expand the series. - Substance Categories with the Greatest Rate of Exposure Increase (Top 25), identifies changes in the year over year rate of substances involved in exposures. - Substance Categories Most Frequently Involved in Pediatric (≤5 years) Deaths, provides information related to substances associated with pediatric deaths. - Substance Categories Most Frequently Identified in Drug Identification Calls (Top 25), provides information related to the substances that triggered drug identification (Drug ID) calls to the centers. - Comparisons of Death Data (2006-2009), provides a breakdown of deaths, suicides and pediatric deaths based on the source of the case, either death or death, indirect report. (Death cases that are directly reported to PCs are classified as direct cases and cases that are identified through other sources such as news feeds or medical examiner data, but did not manage nor answer any questions about are classified as death, indirect report.)

For 2009, the population served has been corrected for 2009 in - Growth of the AAPCC Population Served and Exposure Reporting (1983-2009) to include all 50 United States, American Samoa, District of Columbia, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands. Citation2–6.

Table 1A. Growth of the AAPCC Population Served and Exposure Reporting (1983–2009)

This year, further enhancements for clarity were made to the age labels in the summary tables. All major age brackets were conformed to the following major categories: ≤5 years, 6 – 12 years, 13 – 19 years, ≥ 20 years, Unknown Adult, Unknown Child and Unknown Age. Last year the ≥ 20 years age bracket included ≥ 20 years and Unknown Adult and the Unknown Age bracket included Unknown Child and Unknown Age. Starting this year, these age brackets were reported separately for , , , , , and . Separation of the age brackets did not affect the total data reported. Also, it is important to note that NPDS age values may only be integers. So recorded age cannot be 5½ or 20½, they are recorded as 5 or 20 respectively.

Additional information has been added to 10 existing tables. Raw data counts were added to the existing percentages for and . For each route on a percentage of cases was provided in addition to the previously provided data. which displays the number of substances involved in human exposure cases has been extended to include the number of substances for fatality cases. The series has historically provided information related to the number of substances reported. A case may involve more than one substance and may, therefore, contribute to more than one count in the series tables reported previously. This year the series tables contain additional information related to those cases that involve only one substance. Both the raw counts for single-substance cases and the percentage of single-substance cases have been added to , , and .

This year, lists human exposures with medical outcome of death or death, indirect report regardless of RCF score. Cases are denoted by their Annual Report ID for ease of case retrieval. Pregnancy status is clearly indicated in the report layout although there were no reports of death involving a pregnant patient this year. The Fatality Review process continued with the new system introduced in 2007. However, the fatality case selection process for narrative publication excluded cases with medical outcome of death, indirect report for the last 2 years.

Additionally, the calculations and column headings in several tables have been enhanced this year. These table columns are defined as follows:

This table counts the number of human exposure cases that resulted in the outcome of death or death, indirect. This report indicates that there were 21 pediatric fatality cases where the substances were determined to have contributed to the death where the patient was ≤5 yrs old.

, , ,

All substances column – This column displays the number of substances that were related to any human exposure case regardless of the Relative Contribution to Fatality value. This was the only column in previous reports.

Single substance exposures column – This column, added this year, displays the number of human exposure cases that had one substance (one case, one substance) regardless of Relative Contribution to Fatality.

We have replaced the term All Mentions with the more descriptive term, All Substances, meaning each total category count includes every substance from every exposure that belongs in that category. Thus all substances are counted from every exposure in the 2009 database.

&

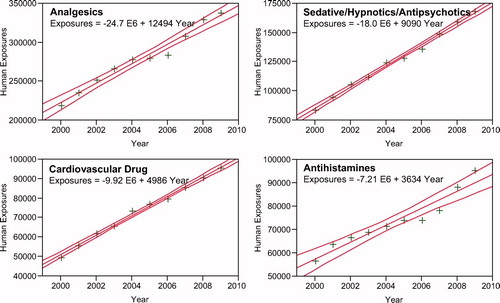

(new this year) reports the 25 categories which were increasing the most rapidly over the last 10 years. shows the linear regressions for the top 4 categories. As 17B provides the complimentary data to , we numbered it and renumbered 17B-D as 17C-E.

(new this year) reports the 25 most frequent categories of drugs identified in 2009.

All substances column - This column displays the number of substances that were related to any human exposure case that was determined to be undoubtedly responsible, probably responsible or contributory by the AAPCC review team. This was the only column in previous reports.

Single substance exposures column – This column (new this year) displays the number of human exposure cases that had one substance (one case, one substance) AND was determined to be undoubtedly responsible, probably responsible or contributory by the AAPCC fatality review team.

Although calculations have not changed since 2006, the column headings have changed:

Column 1: All Exposures displays the number of times the specific generic code was reported in all human exposure cases. If a human exposure case has multiple instances of a specific generic code it is only counted once.

Column 2: Single substance exposures column – This column was previously named ‘No. of Single Exposures’ and was renamed this year for clarity displays the number of human exposure cases that had one substance (one case, one substance). The succeeding columns (Age, Reason, Treatment Site, and Outcome) show selected detail from these single-substance exposure cases. Death cases are only those that had a relative contribution to fatality of 1-undoubtedly responsible, 2-probably responsible or 3-contributory.

Figures

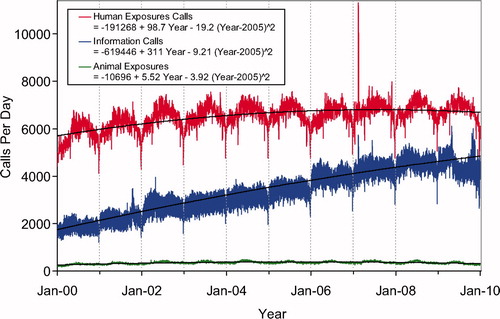

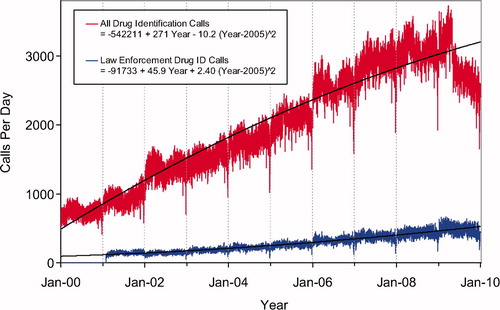

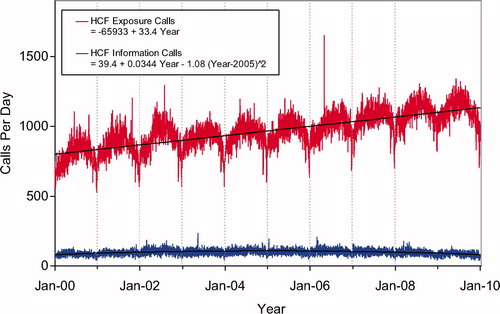

Second order (quadratic) least squares regression for 2000-2009 has been included and shows a statistically significant departure from linearity (declining rate of increase) for Human Exposure Calls, Information Calls, Animal Exposure Calls. All Drug ID Calls and Law Enforcement Drug ID Calls are increasing at an increasing rate ( and ). This year we added , a graphic summary and analyses of Health Care Facility (HCF) Exposure Calls (increasing linearly) and HCF Information Calls (rate is declining since 2005).

The NPDS Application

In 2009, numerous enhancements were introduced in the NPDS web-based application. Many of these focused on surveillance and are described in the Surveillance Section. Others were primarily focused on extending the enterprise reporting tools available for extracting and analyzing the data. Fourteen reports that provide system usage information were added. These reports identify a variety of information about the user community such as identifying the most popular enterprise reports.

The Case Log Reports were extended to include additional parameters including Clinical Effects. Results can now be displayed as aggregated counts, time series graphs (line and bar), US Map, or the traditional case listing. The user may also select the specific data that is included for each case in the usual case listing. Previously the NPDS reports were restricted to a single calendar year. Twenty-eight reports were modified to allow the user to run the report for any time period between 1 January 2000 and the current date. In order to assist the user with selecting the appropriate generic codes and/or product codes for a specific report, 2 new functions were added to the NPDS system. These functions display the generic codes and product codes in a classification tree hierarchy with major and minor generic code categories. This eliminates the need for the user to manually enter a list of generic or product codes and reduces typographical errors. Finally, a new data quality report was introduced that can be performed for an individual PC or nationally. The results of this report provide insight into how NPDS data quality can be maintained and improved. Additional information is also provided by the 2 new Case Log Counts reports. These reports allow the user to extract distributions for a user defined data item such as medical outcome. The user is allowed to define up to 16 different parameters to filter the cases for the result stratification desired. For example, a user may request case counts by medical outcome for exposure cases that involved female patients in their 30s.

NPDS aggregate and case detail web services operate continuously, allowing external systems or viewers to analyze NPDS data in ways not otherwise possible in the NPDS application. The aggregate web service provides total call volume, human exposure call volume, or clinical effects counts allowing an external system such as RODS (Real-time Outbreak and Disease Surveillance, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Biomedical Informatics) to create time-series. Unique to NPDS, the aggregate case count web service is not only accessible by external computer systems but also directly by system users to create their own time series without the need for external system software. Two state health departments utilize the case detail web service to analyze data from their PCs. Four state health departments access the aggregate count web service for data. The web services allow NPDS data to be provisioned in a federated manner where the data is always current in NPDS and can be readily accessed as needed without the need for costly cloning and warehousing.Citation7

Limitations and Plans

As outlined above, the exposure reports and information questions which comprise NPDS are collected from the spontaneous, self-reported calls made to the US PCs. These reflect the limitations of this type of reporting system (see DISCLAIMER). The current AAPCC generic code system categorizes combination products in most cases by their active ingredients and tables are ordered by these groupings. Thus our current review and reporting methods do not distinguish between the individual components of a combination product.

Nonetheless the scope and immediacy of these data have much to offer. In particular the 27 year history offers a unique opportunity to assess the long term (secular) trends in exposures and information calls.

There are a number of plans to improve the data system and reporting for 2009 and beyond including:

Enhancements to NPDS Real-time geographic information system (GIS) with more data display options for appropriate data analyses;

Improvements in data quality edits;

Security paradigm enhancements to support product specific product access for reports and surveillance;

Aggregate enterprise report modifications to span multiple years or parts of years;

Enterprise report enhancements;

New auto-upload requirements and improved solution;

Lexicon based analysis of the current generic code system to better meet current exposure tracking and surveillance needs.

These and other initiatives are under continuous review by the AAPCC Board, NPDS Steering Committee, and CDC.

Methods

Characterization of Participating Poison Centers (PCs)

61 participating centers submitted data to AAPCC through 30 June 2009, with the total center count decreasing to 60 for the remainder of 2009. Fifty-seven centers (95%) were accredited by AAPCC as of 1 July 2009. The entire population of the 50 states, American Samoa, the District of Columbia, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands was served by the US PC network in 2009.

The average number of human exposure cases managed per day by all US PCs was 6,793. Similar to other years, higher volumes were observed in the warmer months, with a mean of 7,118 cases per day in June compared with 6,584 per day in January. On average, US PCs received a call about a suspected or actual human exposure every 12.7 seconds.

Call Management – Specialized Poison Exposure Emergency Providers

Most PC operations management, clinical education, and instruction are directed by Managing Directors (most are PharmDs and RNs with American Board of Applied Toxicology [ABAT] board certification). Medical direction is provided by Medical Directors who are board-certified physician medical toxicologists. At some PCs, the Managing and Medical Director positions are held by the same person.

Calls received at US PCs are managed by healthcare professionals who have received specialized training in toxicology and managing exposure emergencies. These providers include medical and clinical toxicologists, registered nurses, doctors of pharmacy, pharmacists, chemists, hazardous materials specialists, and epidemiologists. Specialists in Poison Information (SPIs) are primarily registered nurses, PharmDs, and pharmacists. They work under the supervision of a Certified Specialist in Poison Information (CSPI). SPIs must log a minimum of 2,000 calls over a 12 month period to become eligible to take the CSPI examination for certification in poison information. Poison Information Providers (PIPs) are allied healthcare professionals. They manage information-type and low acuity (non-hospital) calls and work under the supervision of a CSPI. Of note is the fact that no nursing or pharmacy school offers a toxicology curriculum designed for PC work and SPIs must be trained in programs offered by their respective PC. Centers are accredited by the AAPCC meeting strict standards and must be reaccredited every 5 years.

NPDS – Near Real-time Data Capture

Launched on 12 April 2006, NPDS is the data repository for all of the US regional PCs. In 2009, 61 of the 61 US PCs uploaded case data automatically to NPDS through 30 June 2009. The center count decreased to 60 as of 30 June 2009. All centers submitted data in near real-time making NPDS one of the few operational systems of its kind. PC staff record calls contemporaneously in 1 of 4 case management systems. Each center uploads case data periodically as it is entered. The time to upload data for all PCs is 19.9 [9.7, 58.7] (median [25%, 75%]) minutes creating a real-time national exposure database and surveillance system.

The web-based NPDS software facilitates querying, reporting and a myriad of surveillance uses allowing AAPCC, its member centers and public health agencies to utilize US exposure data. Users are able to access local and regional data for their own areas and view national aggregate data. The application allows for increased “drill-down” capability and mapping via a geographic information system (GIS). Custom surveillance definitions are available along with ad hoc reporting tools. Information in the NPDS database is dynamic. Each year the database is locked prior to extraction of annual report data to prevent inadvertent changes and ensure consistent, reproducible reports. The 2009 database was locked on 1 October 2010 at 1700 hours EDT.

Annual Report Case Inclusion Criteria

The information in this report reflects only those cases that are not duplicates and classified by the regional PC as CLOSED. A case is closed when the PC has determined that no further follow-up/recommendations are required or no further information is available. Exposure cases are followed to obtain the most precise medical outcome possible. Depending on the case specifics, most calls are “closed” within the first hours of the initial call. Some calls regarding complex hospitalized patients or cases resulting in death may remain open for weeks or months while data continues to be collected. Follow-up calls provide a proven mechanism for monitoring the appropriateness of management recommendations, augmenting patient guidelines and providing poison prevention education, enabling continual updates of case information as well as obtaining final/known medical outcome status to make the data collected as accurate and complete as possible.

Statistical Methods

All tables except the new were generated directly by the NPDS web-based application and can thus be reproduced by any AAPCC member. The Figures and statistics were created using SAS JMP version 6.0.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

NPDS Surveillance

As previously noted, all of the active US PCs upload case data automatically to NPDS. This unique near real-time upload is the foundation of the NPDS surveillance system. This makes possible both spatial and temporal case volume and case based surveillance. NPDS software allows creation of volume and case based definitions. Definitions can be applied to national, regional, state, or ZIP code coverage areas. Geocentric definitions can also be created. This functionality is available not only to the AAPCC surveillance team, but to every regional PC. PCs also have the ability to share NPDS real-time surveillance technology with external organizations such as their state and local health departments or other regulatory agencies. Another NPDS feature is the ability to generate system alerts on adverse drug events and other products of public health interest like contaminated food or product recalls. NPDS can thus provide real-time adverse event monitoring and surveillance for resilience response and situational awareness.

Surveillance definitions can be created to monitor a variety of volume parameters, any desired substance or commercial product in the product database (Micromedex® Healthcare Series [Internet database]. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomson Reuters [Healthcare] Inc.). The database contains over 360,000 entries, or case based definitions using a variety of mathematical options and historical baseline periods from 1 to 10 years. NPDS surveillance tools include:

Volume Alerts Surveillance Definitions

Total Call Volume

Human Exposure Call Volume

Clinical Effects Volume (signs and symptoms, or laboratory abnormalities)

Case Based Surveillance Definitions

Substance

Clinical Effects

Various NPDS data fields linked in Boolean expressions

Incoming data is monitored continuously and anomalous signals generate an automated email alert to the AAPCC's surveillance team or designated regional PC or public health agency. These anomaly alerts are reviewed daily by the AAPCC surveillance team and/or the regional PC that created the surveillance definition. When reports of potential public health significance are detected, additional information is obtained via e-mail or phone from reporting PCs. The regional PC then alerts their respective affected state or local health departments. Public health issues are brought to the attention of the National Center for Environmental Health – Health Studies Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This unique near real-time tracking ability is a unique feature offered by NPDS and the regional PCs.

AAPCC Surveillance Team clinical and medical toxicologists review surveillance definitions on a regular basis to fine-tune the queries. CDC, as well as State and local health departments with NPDS access as granted by their respective regional PCs, also have the ability to create surveillance definitions to respond to emerging public health events.

Fatality Case Review and Abstract Selection

NPDS fatality cases can be recorded as either DEATH or DEATH, INDIRECT REPORT. Medical outcome of death is by direct report. Death, indirect report are deaths that the PC acquired from medical examiners or media, but did not manage nor answer any questions about the death.

Although PCs may report DEATH as an outcome, the death may not be the direct result of the exposure. We define exposure-related fatality as a death judged by the AAPCC Fatality Review Team to be at least contributory to the exposure. The definitions used for the Relative Contribution to Fatality (RCF) classification are defined in Appendix B and the methods to select abstracts for publications is described in Appendix C. For details of the AAPCC fatality review process, see the 2008 annual report.1

Results

2009 Case Summary

In 2009, the participating PCs logged 4,280,391 total cases including 2,479,355 closed human exposure cases (), 116,408 animal exposures (), 1,677,403 information calls (), 6,882 human confirmed nonexposures, and 343 animal confirmed nonexposures. An additional 1,990 calls were still open at the time of database lock. The cumulative AAPCC database now contains nearly 51 million human exposure case records (). A total of 13,010,466 information calls have been logged by NPDS since the year 2000.

shows the human exposures, information calls and animal exposures by day since 2000. Second order (quadratic) least squares regression for 2000-2009 has shown a statistically significant departure from linearity (declining rate of calls since mid-2007) for Human Exposure Calls. Information Calls are showing a declining rate of increase and Animal Exposure Calls have been declining since mid-2005.

Table 1B. Non-Human Exposures by Animal Type

Table 1C. Distribution of Information Calls

A hallmark of PC case management is the use of follow-up calls to monitor case progress and medical outcome. US PCs made 2,814,502 follow-up calls in 2009. Follow-up calls were done in 44.4% of human exposure cases. One follow-up call was made in 21.7% of human exposure cases, and multiple follow-up calls (range 2-128) were placed in 22.7% of cases.

Information Calls to Poison Centers (PCs)

Data from 1,677,403 information calls to PCs in 2009 () was transmitted to NPDS, including calls in optional reporting categories such as prevention/safety/education (33,989), administrative (24,508) and caller referral (72,323).

Second order (quadratic) least squares regression for All Drug ID Calls also showed a declining rate of increase for these calls, whereas, Law Enforcement Drug ID Calls are increasing at an increasing rate (). The most frequent information call was for Drug ID, comprising 1,057,632 calls to PCs during the year. Of these, 126,869 (12.0%) could not be identified over the telephone. The majority of the Drug ID calls were received from the public, followed by law enforcement and health professionals. Most of the Drug ID requests from the public and law enforcement were regarding drugs sometimes involved in abuse; however, these cases were categorized based on the drug's abuse potential without knowledge of whether abuse was actually intended.

Drug information calls increased 4.3% from 2008 (230,084 calls) to 2009 (239,943) and comprised 14.3% of all information request calls. Of these, the most common requests were in regards to therapeutic use and indications, followed by drug-drug interactions, questions about dosage and inquiries of adverse effects. Environmental inquiries comprised 1.6% of all information calls. Of these environmental inquiries, questions related to cleanup of mercury (thermometers and other) remains the most common followed by questions involving pesticides.

Of all the information calls, poison information comprised 4.6% of the requests with inquiries involving general toxicity the most common followed by questions involving food preparation practices, plant toxicity and safe use of household products.

Exposure Calls to Poison Centers (PCs)

shows a graphic summary and analyses of Health Care Facility (HCF) Exposure and HCF Information calls. HCF Exposure Calls did not depart from linearity (continued to increase at a steady rate) while the rate of HCF Information Calls has been declining since early 2005. This linearly increasing use of the PCs for the more serious exposures (HCF calls) is important in the face of the declining growth of all exposure and information calls. The 2 May 2006, exposure data spike on the figure was the result of 602 children in a Midwest school reporting a noxious odor which caused anxiety, but resolved without sequalae.

Fig. 3. Health Care Facility (HCF) Exposure Calls and HCF Information Calls by Day since 1 January 2000. Black lines show least-squares first and second order regressions – linear regression for HCF Exposure Calls (second order term was not statistically significant) and second order regression for HCF Information Calls. All terms shown were statistically significant for each of the 2 regressions.

(Nonpharmaceuticals) and (Pharmaceuticals) provide summary demographic data on patient age, reason for exposure, medical outcome, and use of a health care facility for all 2,479,355 human exposure cases, presented by substance categories.

Column 1: All Exposures displays the number of times the specific generic code was reported in all human exposure cases. If a human exposure case has multiple instances of a specific generic code it is only counted once.

Column 2: Single substance exposures column – This column was previously named ‘No. of Single Exposures’ and was renamed this year for clarity displays the number of human exposure cases that had one substance (one case, one substance). The succeeding columns (Age, Reason, Treatment Site, and Outcome) show selected detail from these single-substance exposure cases. Death cases are only those that had a relative contribution to fatality of 1-undoubtedly responsible, 2-probably responsible or 3-contributory.

and restrict the breakdown columns to single-substance cases. Prior to 2007, when multi-substance exposures were included, a relatively innocuous substance was mentioned in a death column when, for example, the death was attributed to an antidepressant, opioid, or cyanide. This subtlety was not always appreciated by the user of this table. The restriction of the breakdowns to single-substance exposures should increase precision and reduce misrepresentation of the results in this unique by-substance table. Single substance cases reflect the majority (90.4%) of all exposures ().

and tabulate 2,849,086 substance-exposures, of which 2,241,191 were single-substance exposures including 1,176,304 (52.5%) nonpharmaceuticals and 1,064,887 (47.5%) pharmaceuticals.

In 16.8% of single-substance exposures that involved pharmaceutical substances, the reason for exposure was intentional, compared to only 3.2% when the exposure involved a nonpharmaceutical substance. Correspondingly, treatment in a health care facility was provided in a higher percentage of exposures that involved pharmaceutical substances (26.5%) compared with nonpharmaceutical substances (14.0%). Exposures to pharmaceuticals also had more severe outcomes. Of single-substance exposure-related fatal cases, 497 were pharmaceuticals compared with 221 nonpharmaceuticals.

Age and Gender Distributions

The age and gender distribution of human exposures is outlined in . Children younger than 3 years were involved in 38.9% of exposures and children younger than 6 years accounted for just over half of all human exposures (51.9%). A male predominance is found among cases involving children younger than 13 years, but this gender distribution is reversed in teenagers and adults, with females comprising the majority of reported exposures.

Caller Site and Exposure Site

As shown in , of the 2,479,355 human exposures reported, 75.8% of calls originated from a residence (own or other) but 93.8% actually occurred at a residence (own or other). Another 16.4% of calls were made from a health care facility. Exposures occurred in the workplace in 1.5% of cases, schools (1.3%), health care facilities (0.3%), and restaurants or food services (0.2%).

Table 2. Site of Call and Site of Exposure, Human Exposure Cases

Table 3. Age and Gender Distribution of Human Exposures

Exposures in Pregnancy

Exposure during pregnancy occurred in 8,005 women (0.32% of all human exposures). Of those with known pregnancy duration (n = 7,302), 31.5% occurred in the first trimester, 38.0% in the second trimester, and 30.4% in the third trimester. Most (72.6%) were unintentional exposures and 20.3% were intentional exposures. There were no deaths involving pregnant females in 2009.

Multiple Patients

In 2009, 9.5% (234,811) of human exposures involved multiple patients. Examples of these include siblings sharing found medication, multiple victims of carbon monoxide exposure such as a family, or multiple patients inhaling vapors at a hazardous material spill.

Chronicity

Most human exposures, 2,239,950 (90.3%) were acute cases (single, repeated or continuous exposure occurring over 8 hours or less) compared to 801 acute cases of 1,544 fatalities (51.9%). Chronic exposures (continuous or repeated exposures occurring over > 8 hours) comprised 1.9% (47,118) of all human exposures. Acute-on-chronic exposures (single exposure that was preceded by a continuous, repeated, or intermittent exposure occurring over a period greater than eight hours) numbered 167,047 (6.7%).

Reason for Exposure

The reason for most human exposures was unintentional (82.4%); unintentional general reason code was reported in 59% of all exposures (). Unintentional misuse comprised 5.1% of all exposures. Therapeutic errors accounted for 11.2% of exposures. Of the total 276,694 therapeutic errors, the most common scenarios for all ages included: inadvertent double-dosing in (31.4%) cases, wrong medication taken or give (14.7%), other incorrect dose (13.7%), doses given/taken too close together (9.6%) and inadvertent exposure to someone else's medication (9.0%). The types of therapeutic errors observed are different for each age group and are summarized in .

Table 4. Distribution of Agea and Gender for Fatalitiesb

Table 5. Number of Substances Involved in Human Exposure Cases

Table 6A. Reason for Human Exposure Cases

Table 6B. Scenarios for Therapeutic Errors by Agea

Intentional exposures accounted for 13.9% of human exposures. Suicidal intent was suspected in 8.9% of cases, intentional misuse in 2.3% and intentional abuse in 1.9%. Unintentional exposures outnumbered intentional exposures in all age groups with the exception of age 13-19 years (). Intentional exposures were reported as frequently as unintentional exposures in patients aged 13-19 years. In contrast, of the 1,158 reported fatalities, the majority reason reported for children ≤5 years was unintentional while most fatalities in adults (≥ 20 years) were intentional ().

Table 7. Distribution of Reason for Exposure by Age

Table 8. Distribution of Reason for Exposure and Age for Fatalitiesa

Table 9. Route of Exposure for Human Exposure Cases

Route of Exposure

Ingestion was the route of exposure in 83.9% of cases (Table 9), followed in frequency by dermal (7.25%), inhalation/nasal (5.35%), and ocular routes (4.5%). For the 1,158 exposure-related fatalities, ingestion (85.1%), inhalation/nasal (8.8%), and parenteral (3.5%) were the predominant exposure routes.

Clinical Effects

The NPDS database allows for the coding of up to 131 different clinical effects (signs, symptoms, or laboratory abnormalities) for each case. Each clinical effect can be further defined as related, not related, or unknown if related. Clinical effects were coded in 849,516 (34.3%) cases. (17.6% had 1 effect, 8.9% had 2 effects, 4.6% had 3 effects, 1.8% had 4 effects, 0.7% had 5 effects, and 0.7% had >5 effects coded). Of clinical effects coded, 79.7% were deemed related to the exposure(s), 9.1% were considered not related, and 11.2% were coded as unknown if related.

The duration of effect is required for all cases that report at least one clinical effect and have a medical outcome of minor, moderate or major effect (n = 455,084). demonstrates an increasing duration of the clinical effects observed with more severe outcomes.

Case Management Site

The majority of cases reported to PCs were managed in a non–health care facility (72.5%), usually at the site of exposure, primarily the patient's own residence (). Another 1.8% of cases were referred to a health care facility but refused to go. Treatment in a health care facility was rendered in 24.1% of cases.

Table 10. Management Site of Human Exposures

Of the 597,787 cases managed in a health care facility, 291,545 (48.8%) were treated and released, 95,429 (16.0%) were admitted for critical care, and 60,122 (10.1%) were admitted for noncritical care.

The percentage of patients treated in a health care facility varied considerably with age. Only 11.2% of children ≤5 years or younger and only 13.2% of children between 6 and 12 years were managed in a health care facility compared with 22.1% of teenagers (13-19 years) and 40.2% of adults (age ≥20 years).

Medical Outcome

displays the medical outcome of the human exposure cases distributed by age, showing a greater incidence of severe outcomes in the older age groups. compares medical outcome and reason for exposure and shows a greater frequency of serious outcomes in intentional exposures.

Table 11. Medical Outcome of Human Exposure Cases by Patient Agea

Table 12. Medical Outcome by Reason: Human Exposuresa

Decontamination Procedures and Specific Antidotes

and outline the use of decontamination procedures, specific antidotes, and measures to enhance elimination in the treatment of patients reported in the NPSD database. These must be interpreted as minimum frequencies because of the limitations of telephone data gathering.

Ipecac-induced emesis for poisoning continues to decline as shown in and . Ipecac was administered in only 330 (<0.01%) pediatric exposures in 2009. The continued decrease in ipecac syrup use in the last decade was likely a result of ipecac use guidelines issued in 1997 by the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology; European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists and updated in 2004.Citation8 , Citation9 In a separate report, the American Academy of Pediatrics concluded not only that ipecac should no longer be used routinely as a home treatment strategy, but also recommended disposal of ipecac currently in homes.Citation10

Table 13. Duration of Clinical Effects by Medical Outcome

Table 14. Decontamination and Therapeutic Interventions

Table 15. Therapy Provided in Human Exposures by Age

Table 16A. Decontamination Trends (1985–2009)

Table 16B. Decontamination Trends: Total Human and Pediatric Exposures ≤5 Years (2009)a

Top Substances in Human Exposures

presents the most common 25 substance categories, listed by frequency of human exposure. This ranking provides an indication where we might focus public health resources on prevention, as well as the types of exposures PCs frequently manage. It is relevant to know whether exposures to these substances are increasing or decreasing. We examined exposures per year over the last decade for the change over time for each of the 67 major generic categories via least squares linear regression. The calls per year were increasing for 42 and decreasing for 25 of the 67 categories. The change over time for the 10 yearly values was statistically significant (p < 0.05) for 52 of the 67 categories. shows the 25 categories which were increasing the most rapidly. Statistical significance of the 25 regressions can be verified by noting the 95% confidence interval on the rate of increase excludes zero. shows the linear regressions for the top 4 increasing categories in .

and present exposure results for children and adults, respectively, and show the differences between substance categories involved in pediatric and adult exposures.

(new this year) reports the 25 categories of substances most frequently involved in pediatric (≤5 years) fatalities in 2009.

(new this year) reports the 25 Drug ID categories most frequently identified in 2009. The most often identified drug category is miscellaneous and unknown – this category includes medications which could not be identified and for which no answer recorded (null response). The null response is permitted because the product identified is not a required field for Information Calls. Drug ID information is of value to AAPCC, public health, public safety, and regulatory agencies. Internet based resources do not allow data capture nor do they afford the caller the ability to speak with a specialist in poison information if the inquiry is more than a drug identification question. Proper resources to continue this vital public service are essential, especially since the top 10 substance categories include antibiotics as well as drugs with widespread use and abuse potential such as opioids and benzodiazepines.

Distribution of Suicides

shows the modest variation in the distribution of suicides over the past 2 decades as reported to the NPDS national database (45-68%). Since 1985, the percent of fatal cases has increased from 0.036% to 0.070% and the percent of pediatric cases has decreased from 6.1% to 2.4%.

Plant Exposures

provides the number of times the specific plant occurred in NPDS. The 25 most commonly involved plant species and categories account for 24,344 of a total number of plants that were reported (58,933). The top 3 categories in the table are essentially synonymous for unknown plant and comprise 14.3% (8,427/58,933) of all plant exposures. For a variety of reasons it was not possible to make a precise identification in these 3 groups. The top 5 most frequent plant exposures where a positive plant identification was made were (descending order): Spathiphyllum spp. Not otherwise specified (NOS), Phytolacca americana (L.), Toxicodendron radicans (L.), Philodendron spp. (NOS), and Ilex spp. (NOS).

Table 17A. Substance Categories Most Frequently Involved in Human Exposures (Top 25)

Table 17B. Substance Categories with the Greatest Rate of Exposure Increase (Top 25)

Table 17C. Substance Categories Most Frequently Involved in Pediatric (≤5 years) Exposures (Top 25)a

Table 17D. Substance Categories Most Frequently Involved in Adult (≥20 years) Exposures (Top 25)a

Table 17E. Substance Categories Most Frequently Involved in Pediatric (≤5 years) Deathsa

Table 17F. Substance Categories Most Frequently Identified in Drug Identification Calls (Top 25)

Table 18. Categories Associated with Largest Number of Fatalities (Top 25)a

Table 19A. Comparisons of Death Data (1985–2009)a

Table 19B. Comparisons of Death Data (2006–2009)a

Table 20. Frequency of Plant Exposures (Top 25)

Table 21. Listing of fatal nonpharmaceutical and pharmaceutical exposures

Table 22A. Demographic profile of SINGLE-SUBSTANCE nonpharmaceuticals exposure cases by generic category

Table 22B. Demographic profile of Single-Substance pharmaceuticals exposure cases by generic category

Deaths and Exposure-related Fatalities

A listing of cases () and summary of cases (, , , , , , , , and ) are provided for fatal cases for which there exists reasonable confidence that the death was a result of that exposure (exposure-related fatalities). Of the 1,544 cases initially reviewed, 1,158 were judged exposure-related fatalities (Relative Contribution to Fatality Category = 1-Undoubtedly responsible, 2-Probably responsible, or 3-Contributory). The remaining 386 cases were judged as follows: 62: RCF = 4-Probably not responsible, 45: 5-Clearly not responsible, and 279: RCF = 6-Unknown.

Deaths are sorted in according to the category, patient age and substance deemed most likely responsible for the death (Substance Rank). The Cause Rank permits the PC to judge 2 or more substances as indistinguishable in terms of cause, e.g., 2 substances which appear equally likely to have caused the death could have Substance Rank of 1,2 and Cause Rank of 1,1. Additional agents implicated are listed below the primary agent in the order of their contribution to the fatality.

As shown in , a single substance was implicated in 90.4% of reported human exposures, and 9.6% of patients were exposed to 2 or more drugs or products. The exposure-related fatalities involved a single substance in 491 cases (42.4%), 2 substances in 275 cases (23.7%), 3 in 167 cases (14.4%), and 4 or more in the balance of the cases (). The cross-references at the end of each major category section list all cases that identify this substance as other than the primary substance.

The Annual Report ID number [bracketed] indicates that the abstract for that case is included in Appendix C. The letters following the Annual Report ID number include: i = death, indirect report after the fatality occurred in 46 cases (4.0%), p = prehospital cardiac and/or respiratory arrest in 402 (34.7%), h = hospital records reviewed in 223 cases (19.3%), a = autopsy report reviewed in 325 cases (28.1%).

The distribution of NPDS RCF was: 1 = Undoubtedly responsible in 518 cases (44.7%), 2 = Probably responsible in 461 cases (39.8%), 3 = Contributory in 179 cases (15.5%).

All fatalities – all ages

presents the age and gender distribution for these 1,158 exposure-related fatalities. The age distribution of reported fatalities is similar to that in past years with 93.2% (1,079 of 1,158) of fatal cases occurring in adults (age > 19 years). Although children younger than 6 years were involved in the majority of exposures, the 21 fatalities comprised just 1.8% of the exposure-related fatalities. Most (70.9%) of the fatalities occurred in 20-to 59-year-old individuals.

lists each of the 1,158 human fatalities along with all of the substances involved. Please note: the Substance listed in column 3 of was chosen to be the most specific generic name based upon the substances entered for that case. This Substance name may not agree with the AAPCC generic categories used in the summary tables (including ).

lists the top 25 substance categories associated with reported fatalities and the number of single substance exposure fatalities for that category – sedative/hypnotics/antipsychotics, cardiovascular drugs, opioids, and acetaminophen in combination products, lead this list followed by antidepressants, acetaminophen alone, alcohols, and stimulants/street drugs. Although sedative/hypnotics/antipsychotics ranks 4th and antidepressants 7th among the most frequent exposures (), there is otherwise little concordance between the frequency of exposures to a substance and the number of fatalities. Note that summarizes all substances to which a patient was exposed (i.e., a patient exposed to an opioid may have also been exposed to 1 or more other products).

The first ranked substance was a pharmaceutical in 925 of the 1,158 fatalities (79.9%). These 925 first ranked pharmaceuticals included:

441 analgesics (100 acetaminophen, 62 acetaminophen/hydrocodone, 49 methadone, 37 salicylate);

123 cardiovascular drugs (18 cardiac glycoside, 18 verapamil, 14 amlodipine, 12 diltiazem, 11 metoprolol, 8 diltiazem (extended release));

91 antidepressants (20 amitriptyline, 8 doxepin, 7 bupropion, 7 bupropion (extended release);

79 sedative/hypnotic/antipsychotics (20 quetiapine, 11 alprazolam, 6 diazepam, 6 zolpidem);

65 stimulants/street drugs (22 heroin, 16 cocaine, 12 methamphetamine, 4 MDMA)

The exposure was acute in 621 (53.7%), A/C = acute on chronic in 250 (21.6%), C = chronic exposure in 77 (6.6%) and U = unknown in 210 (18.1%).

A total of 3,375 tissue concentrations for 1 or more related analytes were reported in 457 cases (39.5%).

Route of exposure was: Ingestion in 985 cases (79.0%), inhalation/nasal in 102 cases (7.9%), parenteral in 24 cases (2.1%). ()

Intentional exposure reasons: Suspected suicide in 652 cases (56.3%), Intentional-Abuse in 97 cases (17.4%), Intentional-Misuse in 38 cases (3.3%).

Unintentional exposure reasons: Environmental in 37 cases (3.2%), Therapeutic error in 24 cases (2.1%), Misuse in 14 cases 1.2%). ()

Acetaminophen/Propoxyphene Fatalities

The current AAPCC generic code system categorizes combination products in most cases by their active ingredients and tables ordered by these groupings. Our current review and reporting methods do not distinguish between the individual components of a combination product. To better understand this issue, an independent team of fatality medical toxicologists reviewed one group of fatality cases (acetaminophen/propoxyphene combination products) as a pilot.

Eight fatalities involved acetaminophen/propoxyphene only – age ranged from 19 to 74 (median 43) year, 5 were female, 6 of the calls were from health care facilities, relative contribution to fatality (RCF) determined by the initial contributor was 1 for 3 cases, 2 for 3 cases, and 3 for 2 cases. An independent team of medical toxicologists (DH Jang and LS Nelson) reviewed these cases for the relative contribution of acetaminophen and propoxyphene to the fatality. Their determination of the relative contribution to fatality (RCF) based on the reports was 1 for 1 case, 2 for 1 case, and 3 for 2 cases, 4 or 6 for 4 cases. In none of the cases was acetaminophen clearly the cause of death. In 6 of 8 cases other causes were judged more likely than propoxyphene to have caused the death (propoxyphene was contributory or not involved).

Pediatric fatalities – age ≤5 years

Although children younger than 6 years were involved in the majority of exposures, they comprised 37 of 1,158 (2.4%) of fatalities. These numbers are similar to those reported since 1985 (). The percentage fatalities in children ≤5 years related to total pediatric exposures was 21/1,290,784 = 0.00163%. By comparison, 1,076/853,039 = 0.126% of all adult exposures involved a fatality. Of these 21 pediatric fatalities, 18 (85.7%) were reported as unintentional and 1 (4.7%) were coded as resulting from malicious intent (). These 21 cases included 7 pharmaceuticals and 14 nonpharmaceuticals. The first ranked substances associated with these fatalities included: disc battery (4 cases); methadone and smoke (3 cases each); kerosene (2 cases) and 10 other substances (1 each).

Pediatric fatalities – ages 6-12 years

In the age range 6 to 12 years, there were 10 reported fatalities (), 6 of which were unintentional exposures and 2 intentional exposures. These 10 cases included 3 pharmaceuticals and 7 nonpharmaceuticals. The first ranked substances associated with these fatalities included: carbon monoxide or smoke inhalation (5 cases); air freshener aerosol, benzonatate, isopropranol, quetiapine, senna (1 each).

Adolescent fatalities – ages 13-19 years

In the age range 13 to 19 years, there were 48 reported fatalities (). These 48 cases included 42 pharmaceuticals and 6 nonpharmaceuticals. The first ranked pharmaceuticals associated with these fatalities included: methadone (5 cases); acetaminophen and acetaminophen/diphenhydramine (3 cases each); carbon monoxide, heroin, MDMA, opioid, oxycodone, and unknown drug (2 each) and 23 other substances (1 each).

Of the 48 reported fatalities for adolescents, 32 (66.7%) were suspected suicides, and 7 (14.6%) were intentional abuse exposures (). The suspected suicide percentage is higher than in recent years. The percentage of intentional abuse cases is lower than in recent years (25.8% in 2006 to 35.7% in 2008). As in the past years, only a small number (2 of 48) of adolescent fatalities were coded as being unintentional.

Pregnancy and fatalities

A total of 26 deaths of pregnant women have been reported from the years 2000 through 2008. An average of 2 deaths per year was recorded from 2000 through 2004. Since 2005, the average number of deaths in pregnant women reported to NPDS doubled to 4 per year. The majority (20 of 26) were intentional exposures of misuse, abuse and suspected suicide. There were no deaths in pregnant women reported to NPDS in 2009.

AAPCC Surveillance Results

A key component of the NPDS surveillance system is the variety of monitoring tools available to the NPDS user community. In addition to AAPCC national surveillance definitions, 37 regional PCs utilize NPDS as part of their surveillance programs. Eleven state health departments have been given NPDS access by their regional centers. Since Surveillance Anomaly 1, generated at 2:00 pm EDT on 17 September 2006, over 151,000 anomalies have been detected. More than 600 were confirmed as being of public health significance with regional PCs working collaboratively with their local and state health departments and in some instances CDC on the public health issues identified.

At the time of this report, 378 surveillance definitions run continuously, monitoring case and clinical effects volume and a variety of case based definitions from food poisoning to nerve agents. These definitions represent the surveillance work by many regional PCs, state health departments, the AAPCC, and Health Studies Branch, Division of Environmental Hazards and Health Effects, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2009, the NPDS surveillance application module underwent incremental improvements. These included analysis process enhancements such as clinical effect analysis notes simplification. Surveillance reporting enhancements were also implemented in 2009. More enhancements were scheduled for 2010 including: information call surveillance, animal exposure call surveillance, updates to anomaly status tracking and case based time series reports.

Automated surveillance continues to remain controversial as a viable methodology to detect the index case of a public health event. Uniform evaluation algorithms are not available to determine the optimal methodologies.Citation11 Less controversial is the benefit to situational awareness that NPDS can provide. Typical NPDS surveillance data detects a response to an event rather than event prediction. This aids in situational awareness and resilience during and after a public health event.

On Saturday, 25 April 2009, the Director-General of WHO declared the 2009 H1N1 outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern and recommended that countries intensify surveillance for unusual outbreaks of influenza-like illness and severe pneumonia. Cases were suspected in New York City, Ohio and Kansas.Citation12 The US followed with declaration of a nationwide public health emergency on 26 April 2009. Calls were also coming into US PCs. Several centers had activated Public Health Emergency lines to specifically manage questions from the public. On 1 May 2009 and again on 20 August 2009, AAPCC and Micromedex® activated two H1N1 vaccine product codes (Inactivated and Live, attenuated) in the Poisindex® products database. Earlier in 2009, on 27 April a general product code for the H1N1 virus was activated. These codes allowed PCs to track exposure and medical information calls related to the Pandemic.

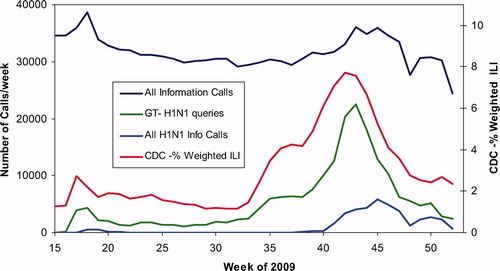

shows a by-week graph of All Information Call data for weeks 15-52 of 2009 showing an unusual “dip” between week 18 and week 43. The bottom line shows All H1N1 Info Calls, i.e., calls where the product was H1N1, the live H1N1 Vaccine, or the H1N1. The red curve shows the weighted % of cases of Influenza Like Illness (ILI) data from CDC.12 The green curve Google Trends for H1N1 over the same interval (relative scale only).Citation13 The similarity in these profiles illustrates the importance of public access to PCs in times of public health events. US PCs represent the only 24/7 365 system always open where anyone can speak to a health care professional at no charge. This data demonstrates how the public utilizes PCs in times of crisis. This unique system can be supported and enhanced to serve as a national public health hotline providing information and management beyond traditional poison exposure calls.Citation12

Fig. 4. All Information Calls, H1N1 Information Calls, CDC Influenza-Like Illness, Google H1N1 queries by Week since 6-Apr-2009. All Information Calls and All H1N1 Calls/week are shown on the left axis, patients with influenza-like illness (ILI) reported to CDC are shown on the right axis. Google Trends for H1N1 is not a scaled variable and is shown at a convenience scale.

Discussion

The exposure cases and information requests reported by PCs in 2009 do not reflect the full extent of PC efforts which also include activities such as poison prevention and education.

NPDS exposure data may be considered as providing “numerator data”, but we lack a true denominator, that is, we do not know the number of actual exposures that occur in the population. NPDS data covers only those exposures which are reported to PCs.

Depending on the source, the numbers may be different, but NPDS regression analyses confirms that all analgesic exposures including opioids and sedatives are increasing year after year. This trend is shown in and . NPDS data mirrors CDC data that demonstrates similar findings.Citation14 Thus NPDS provides a real-time view of these public health issues without the need for data source extrapolations.

Fig. 5. Human Exposure Calls By Year 2000–2009 – Top 4 Categories. Solid lines show least-squares linear regressions for the Human Exposure Calls per year for that category (+). Broken lines show 95% confidence interval on the regression.

One of the limitations of NPDS data has been the perceived lack of fatality case volume compared to other reporting sources. However, when change over time is studied, NPDS is clearly consistent with other public health analyses. One of the issues leading to this problem is the fact that medical record systems seldom have common output streams. This is particularly apparent with the various electronic medical record systems available. It is important to build a federated approach similar to the one modeled by NDPS to allow data sharing, for example, between hospital emergency departments and other medical record systems including medical examiner offices nationwide. Enhancements to NPDS can promote interoperability between NPDS and electronic medical records systems to better trend poison-related morbidity and mortality in the US and internationally.

Summary

Salient findings from this 27th Annual Report include:

The number of human exposure calls in 2009 was less than 2008 and the second order least squares regression for 2000-2009 calls by day departed from linearity (declining rate since mid 2007);

Both total information calls and drug information calls in 2009 were greater than 2008, but the second order least squares regression for 2000-2009 calls by day departed from linearity (declining rate of increase);

Drug identification calls show a distinct drop in late 2009 and the most frequently identified drug is miscellaneous and unknown – it is important to AAPCC to continue providing and improving this important public health service;

HCF information calls have been declining since 2005, but HCF exposure calls are continuing to increase linearly since 2000, suggesting PC use in the more severe cases continues to increase.

Unintentional and intentional exposures continue to be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the US. The near real-time, always current status of NPDS represents a national public health resource to collect and monitor US exposure cases and information calls. The continuing mission of NPDS is to provide a nationwide infrastructure for public health surveillance for all types of exposures, public health event identification, resilience response and situational awareness tracking. NPDS is a model system for the nation and global public health.

Disclaimer

The American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC; http://www.aapcc.org) maintains the national database of information logged by the country's regional Poison Centers (PCs) serving all 50 United States, Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia. Case records in this database are from self-reported calls: they reflect only information providedwhen the public or healthcare professionals report an actual or potential exposure to a substance (e.g., an ingestion, inhalation, or topical exposure, etc.), or request information/educational materials. Exposures do not necessarily represent a poisoning or overdose. The AAPCC is not able to completely verify the accuracy of every report made to member centers. Additional exposures may go unreported to PCs and data referenced from the AAPCC should not be construed to represent the complete incidence of national exposures to any substance(s).

References

- National Poison Data System: Annual reports 1983-2008 [Internet]. Alexandria (VA): American Association of Poison Control Centers; [cited 2010 Oct 1]. Available from: http://www.aapcc.org/dnn/NPDSPoisonData/AnnualReports/tabid/125/Default.aspx

- Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2009 (NST-EST 2009-01). Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, Release Date: December 2009.

- US Census Bureau: International Data Base (IDB) 2009 Midyear population estimate American Samoa [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Census Bureau; [cited 2010 Oct 20] Available from: http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb/country.php

- US Census Bureau: International Data Base (IDB) 2009 Midyear population estimate Guam [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Census Bureau; [cited 2010 Oct 20] Available from: http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb/country.php

- US Census Bureau: International Data Base (IDB) 2009 Midyear population estimate Micronesia, Federated States of [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Census Bureau; [cited 2010 Oct 20] Available from: http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb/country.php

- US Census Bureau: International Data Base (IDB) 2009 Midyear population estimate Virgin Islands, US. [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Census Bureau; [cited 2010 Oct 20] Available from: http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/idb/country.php

- Savel TG, Bronstein A, Duck, M, Rhodes MB, Lee, B, Stinn J, Worthen, K. Using Secure Web Services to Visualize Poison Center Data for Nationwide Biosurveillance: A Case Study [Internet]. Online Journal of Public Health Informatics 2010; 2: 1–9; [cited 2010 Nov 1]. Available from: http://ojphi.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/ojphi/article/view/2920/2505

- Position statement: ipecac syrup. American Academy of Clinical Toxicology; European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1997; 35:699–709.

- American Academy of Clinical Toxicology European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists. Position Paper: Ipecac Syrup. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2004; 42: 133–143.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Policy Statement. Poison treatment in the home. Pediatrics 2003; 112:1182–1185.

- Sosin DM, DeThomasis J. Evaluation challenges for syndromic surveillance–making incremental progress. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004; 53 Suppl: 125–129.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 2009 H1N1 Flu U.S. Situation Update: percentage of visits for influenza-like-illness reported by sentinel providers 2009-2010 [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [cited 2010 Oct 28]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/weeklyarchives2009-2010/data/senAllregt52.htm

- Google trends: H1N1 2009 [Internet]. Mountain View (CA): Google, Inc.; [cited 2010 Oct 25] Available from: http://www.google.com/trends?q = h1n1&ctab = 0&geo = us&geor = all&date = 2009

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. QuickStats: Number of Poisoning Deaths* Involving Opioid Analgesics and Other Drugs or Substances — United States, 1999—2007. MMWR 2010; 59:1026.

- McGraw-Hill's AccessMedicine, Laboratory Values of Clinical Importance (Appendix), Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine 17e. McGraw-Hill Professional; 2008[cited 2010 Nov 1]. Available from: http://www.accessmedicine.com/

- Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies, Eighth Edition>, McGraw-Hill Companies, 2006.

- Dart RC, editor. Medical Toxicology, Third Edition, Philadelphia, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2004.

Appendix A – Acknowledgments

The compilation of the data presented in this report was supported in part through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control AAPCC Contract 200-2007-19121.

The authors wish to express their appreciation to the following individuals who assisted in the preparation of the manuscript: Kathy W. Worthen, Laura J. Rivers, Carol L. Hesse, and Denise A. Martinez.

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Jim Hirt, AAPCC Executive Director and the staff at the AAPCC Central Office for their support during the preparation of the manuscript.

Thanks to David H. Jang, MD, and Lewis S. Nelson, MD, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY for the thoughtful review of the acetaminophen/propoxyphene fatalities.

Poison Centers (PCs)

We gratefully acknowledge the extensive contributions of each participating PC and the assistance of the many health care providers who provided comprehensive data to the PCs for inclusion in this database. We especially acknowledge the dedicated efforts of the Specialists in Poison Information (SPIs) who meticulously coded 4,280,391 calls made to US PCs in 2009.

As in previous years, the initial review of reported fatalities and development of the abstracts was the responsibility of the staff of the participating PCs. These PCs and individuals are listed at the beginning of this report.

Many individuals at each center participate in the review of their centers fatality cases. The following toxicology professionals summarized and prepared their center's fatality data for NPDS:

Alabama Poison Center

Perry Lovely, MD, ACMT

John Fisher, PharmD, DABAT, FAACT

Lois Dorough BSN, RN, CSPI

Arizona Poison and Drug Information Center

Keith Boesen, PharmD, CSPI

F. Mazda Shirazi, MS, MD, PhD, FACEP

Jude McNally RPh, DABAT

Leslie Boyer MD, FACMT

Arkansas Poison & Drug Information Center

Henry F. Simmons, Jr., MD

Pamala R. Rossi, PharmD

Howell Foster, PharmD

Banner Good Samaritan Poison and Drug Information Center

Daniel Brooks, MD

Mary-Ann Calley, RN, CSPI

Jane Klemens, RN, CSPI

Sharyn Welch, RN

Blue Ridge Poison Center

Christopher Holstege, MD

Nathan Charlton, MD

David Lawrence, MD

Brigid Wonderly, RN

Stephen Dobmeier, RN

California Poison Control System – Fresno/Madera Division

Richard J. Geller, MD, MPH

California Poison Control System – Sacramento Division

Timothy Albertson, MD, PhD

Judith Alsop, PharmD

California Poison Control System – San Diego Division

Richard F. Clark, MD

Lee Cantrell, PharmD

Shaun Carstairs, MD

Sean Nordt, MD, PharmD

Allyson Kreshak, MD

Alicia Minns, MD

Joshua Nogar, MD

California Poison Control System – San Francisco

Kent R. Olson, MD

Thanjira Jiranantakan, MD

Susan Kim, PharmD

Alan Tani, PharmD

Raymond Ho, PharmD

Kathryn Meier, PharmD

Sandra Hayashi, PharmD

Tanya Mamantov, MD

Derrick Lung, MD

Patil Armenian, MD

Carolinas Poison Center

Michael C. Beuhler, MD

Marsha Ford, MD

William Kerns II, MD

Anna Rouse Dulaney, PharmD

Central Ohio Poison Center

Marcel J. Casavant, MD, FACEP, FACMT

Heath Jolliff, DO, FACEP, FAAEM

S. David Baker, PharmD, DABAT

Julee Fuller-Pyle

Julie Lecky, BA

Central Texas Poison Center

Ryan Morrissey, MD

Vikhyat Bebarta, MD

Douglas J. Borys, PharmD, DABAT

Children's Hospital of MI Regional Poison Center

Cynthia Aaron, MD

Lydia Baltarowich, MD

Keenan Bora, MD

Bram Dolcourt, MD

Matthew Hedge, MD, ACMT

Susan C. Smolinske, PharmD

Suzanne R. White, MD

Cincinnati Drug and Poison Information Center

G. Randall Bond, MD

Rachel Sweeney, RN

Connecticut Poison Center

Charles McKay, MD

Kathy Hart MD

Jarrett Lefberg, DO

Kevin O'Toole, MD

Bernard C. Sangalli, MS

Florida/USVI Poison Information Center – Jacksonville

Thomas Kunisaki, MD, FACEP, ACMT

Florida Poison Information Center – Miami

Jeffrey N. Bernstein, MD

Richard S. Weisman, PharmD

Florida Poison Information Center – Tampa

Cynthia R. Lewis-Younger, MD, MPH

Pam Eubank, RN, CSPI

Judy Gussett, RN, CSPI

Judy Turner, RN, CSPI

Georgia Poison Center

Robert Geller, MD

Brent W. Morgan, MD

Arthur Chang, MD

Ziad Kazzi, MD

Gaylord P. Lopez, PharmD

Stephanie Hon, PharmD

Andre Matthews, MD

Soumya Pandalai, MD

SaraJane Reedy, MD

Rizwan Riyaz, MD

Hennepin Regional Poison Center

David J. Roberts MD

Elisabeth F. Bilden MD

Deborah L. Anderson PharmD

Samuel J. Stellpflug, MD

Jon B. Cole, MD

Illinois Poison Center

Michael Wahl, MD

Sean Bryant, MD

Indiana Poison Center

James B. Mowry, PharmD

R. Brent Furbee, MD

Iowa Statewide Poison Control Center

Sue Ringling, RN

Edward Bottei, MD

Kentucky Regional Poison Center

George M. Bosse, MD

Henry A. Spiller, MS, RN, DABAT, FAACT

Long Island Regional Poison and Drug Information Center

Thomas R. Caraccio, PharmD, DABAT

Michael McGuigan, MDCM, MBA

Louisiana Poison Center

Mark Ryan, PharmD

Thomas Arnold, MD

Maryland Poison Center

Suzanne Doyon, MD, FACMT

Patrick Dougherty, PharmD

Mississippi Poison Control Center

Robert Cox MD, PhD, DABT, FACMT

Tanya Calcote, RN, CSPI

Missouri Poison Center at SSM Cardinal Glennon

Children's Medical Center

Anthony Scalzo, MD

Shelly Enders, PharmD, CSPI

National Capital Poison Center

Cathleen Clancy, MD, FACMT

Nicole Whitaker, RN, BA, BSN, MEd, CSPI

Nebraska Regional Poison Center

Claudia Barthold, MD

Ronald I. Kirschner, MD

New Jersey Poison Information and Education System

John Kashani, DO

Steven M. Marcus, MD

New Mexico Poison and Drug Information Center

Steven A. Seifert, MD, FAACT, FACMT

New York City Poison Control Center

Maria Mercurio-Zappala, MS, RPh

Robert S. Hoffman, MD

Lewis Nelson, MD

Alex Manini, MD

Silas Smith, MD

Oladapo Odujebe, MD

Jen Prosser, MD

Brenna Farmer, MD

Samara Soghoian, MD

North Texas Poison Center

Brett Roth MD, ACMT, FACMT

Northern Ohio Poison Center

Lawrence S. Quang, MD

Alfred Aleguas, PharmD

Gerald Maloney, MD

Northern New England Poison Center

Theresa Maher, MFA

Tamas Peredy, MD

Oklahoma Poison Control Center

William Banner, Jr., MD, PhD, ABMT

Lee McGoodwin, PharmD, MS, DABAT

Oregon Poison Center

Zane Horowitz, MD

Sandra L. Giffin, RN, MS

Palmetto Poison Center

William H. Richardson, MD

Jill E. Michels, PharmD

Pittsburgh Poison Center

Kenneth D. Katz, MD

Rita Mrvos, BSN

Edward P. Krenzelok, PharmD

Puerto Rico Poison Center

José Eric Díaz-Alcalá, MD

Regional Center for Poison Control and Prevention

Serving Massachusetts and Rhode Island

Michele Burns Ewald, MD

David Kemmerer, RN

Nilam Patil, MD

Kishan Kapadia, MD

Alfred Aleguas, PharmD

Regional Poison Control Center – Children's Hospital of Alabama

Diane Smith, RN, CSPI

Valoree Stanley, RN, CSPI

Erica Liebelt, MD, FACMT

Michele Nichols, MD

Rocky Mountain Poison & Drug Center

Carol L. Hesse, RN, CSPI

Alvin C. Bronstein, MD, FACEP, FACMT

Ryan Chuang, MD

Andrew Monte, MD

Shan Yin, MD, MPH

Amy Zosel, MD

Denise Martinez

South Texas Poison Center

Douglas Cobb, RPh

Cynthia Abbott-Teter, PharmD

Miguel C. Fernandez, MD

George Layton, MD

C. Lizette Villarreal, MA

Southeast Texas Poison Center

Wayne R. Snodgrass, MD, PhD, FACMT

Jon D. Thompson, MS, DABAT

Jean L. Cleary, PharmD, CSPI

Tennessee Poison Center

John G. Benitez, MD, MPH

Saralyn Williams, MD

Donna Seger, MD

Texas Panhandle Poison Center

Shu Shum, MD

Jeanie E. Jaramillo, PharmD

Cristie Johnston, RN, CSPI

The Poison Control Center at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

Allison A. Muller, PharmD

Kevin Osterhoudt, MD

The Ruth A. Lawrence Poison and Drug Information Center

Ruth A. Lawrence, MD

Norma Barton, BS Pharm, CSPI

Timothy J. Wiegand, MD

University of Kansas Hospital Poison Control Center

Tama Sawyer, PharmD

Upstate NY Poison Center

Jeanna M. Marraffa, PharmD

Jamie Nelsen, PharmD

Christine M. Stork, PharmD

Utah Poison Control Center

Martin Caravati, MD, MPH

Virginia Poison Center

Rutherfoord Rose, PharmD

Kirk Cumpston, DO

Brandon Wills, DO

Washington Poison Center

William T. Hurley, MD, FACEP

David Serafin, CPIP

West Texas Regional Poison Center

John F. Haynes, Jr., MD, ABEM, ABMT

Stephen W. Borron, MD, MS, FACEP,

FACMT Leo Artalejo III, PharmD

Hector L. Rivera, RPh

West Virginia Poison Center

Lynn F. Durback-Morris RN, BSN, MBA, DABAT

(Posthumous Recognition)

Anthony F. Pizon, MD, ABMT

Western New York Poison Center

Prashant Joshi, MD

Ashley N. Webb, PharmD, MSc

Wisconsin Poison Center

David D. Gummin, MD

Lori Rohde, SPI, Poison Center Supervisor

Fatality Review Team

The Lead and Peer review of the 2009 fatalities was carried out by the 29 individuals listed here. The authors and the AAPCC wish to express our appreciation for their volunteerism, dedication, hard work and good will in completing this task in a limited time.

Alfred Aleguas Jr., PharmD, DABAT, Managing Director, Northern Ohio Poison Center, Cleveland, OH

Anna M. Rouse*, PharmD, DABAT, Assistant Director, Education, Carolinas Poison Center

Ann-Jeannette Geib, MD, Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick NJ

Bernard C. Sangalli*, MS, DABAT, Director, Connecticut Poison Center

Charles McKay, MD, Associate Medical Director, Connecticut Poison Control Center, University of Connecticut School of Medicine

Cynthia R. Lewis-Younger, MD, MPH, Managing/Medical Director, Florida Poison Information Center-Tampa

Daniel E. Brooks*, MD, Department of Medical Toxicology, Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center, Phoenix

David Gummin, MD, Wisconsin Poison Center, Milwaukee, WI

Elizabeth J. Scharman, PharmD, DABAT, BCPS, FAACT, Director West Virginia Poison Center

Heath Jolliff, DO, Central Ohio Poison Center, Columbus, Ohio

Henry Spiller, MS, DABAT, FAACT, Kentucky Regional Poison Center, Louisville, KY

Howell Foster, PharmD, DABAT, Arkansas Poison & Drug Information Center

Jill E. Michels, PharmD, DABAT, Managing Director, Palmetto Poison Center, SC

Judith A. Alsop, PharmD, DABAT, California Poison Control System - Sacramento Division

Karen E. Simone, PharmD, DABAT, Director, Northern New England Poison Center, Maine Medical Center

Kathryn Meier, PharmD, DABAT, Senior Toxicology Management Specialist, California Poison Control System, San Francisco Division

Lewis Nelson, MD, New York City Poison Center, New York University School of Medicine

Luke Yip*, MD, FACMT, FACEM, FACEP, Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center, Denver, CO

Lynn Durback-Morris**, RN, MBA, DABAT, CSPI, Supervisor of Operations, West Virginia Poison Center

Maria Mercurio-Zappala, RPh, MS, DABAT, FAACT Managing Director, NYC Poison Control Center

Mark Su, MD, FACEP, FACMT, Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, Director, Fellowship in Medical Toxicology, Department of Emergency Medicine, North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, NY

Michael Levine, MD, Department of Medical Toxicology, Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center, Phoenix

Richard J. Geller*, MD, MPH, FACP, Medical and Managing Director, California Poison Control System, Fresno/Madera

Robert B. Palmer, PhD, DABAT, Toxicology Associates, Denver, CO; Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center, Denver, CO

S. David Baker, PharmD, DABAT, Managing Director, Central Ohio Poison Center

Susan C. Smolinske, PharmD, DABAT, Children's Hospital of Michigan Regional Poison Control Center, Detroit

Tammi Schaeffer, DO, Rocky Mountain Poison & Drug Center, Denver, CO

Tim Wiegand, MD; Director, Ruth A. Lawrence -Finger Lakes Poison and Drug Information Center, Rochester, NY

William T. Hurley, MD, Medical Director, Washington Poison Center