Abstract

Background: This is the 26th Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC; http://www. aapcc.org) National Poison Data System (NPDS). During 2008, 60 of the nation's 61 US poison centers uploaded case data automatically. The median upload time was 24 [7.2, 112] (median [25%, 75%]) minutes creating a real-time national exposure and information database and surveillance system.

Methodology: We analyzed the case data tabulating specific indices from NPDS. The methodology was similar to that of previous years. Where changes were introduced, the differences are identified. Poison center cases with medical outcomes of death were evaluated by a team of 28 medical and clinical toxicologist reviewers using an ordinal scale of 1–6 to determine Relative Contribution to Fatality (RCF) from the exposure to the death.

Results: In 2008, 4,333,012 calls were captured by NPDS: 2,491,049 closed human exposure cases, 130,495 animal exposures, 1,703,762 information calls, 7,336 human confirmed nonexposures, and 370 animal confirmed nonexposures. The top five substances most frequently involved in all human exposures were analgesics (13.3%), cosmetics/personal care products (9.0%), household cleaning substances (8.6%), sedatives/hypnotics/antipsychotics (6.6%), and foreign bodies/toys/miscellaneous (5.2%). The top five most common exposures in children age 5 or less were cosmetics/personal care products (13.5%), analgesics (9.7%), household cleaning substances (9.7%), foreign bodies/toys/miscellaneous (7.5%), and topical preparations (6.9%). Drug identification requests comprised 66.8% of all information calls. NPDS documented 1,756 human exposures resulting in death with 1,315 human fatalities deemed related with an RCF of at least contributory (1, 2, or 3).

Conclusions: Poisoning continues to be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the US. The near real-time, always current status of NPDS represents a national resource to collect and monitor US poisoning exposure cases and information calls. NPDS continues its mission as one of the few real-time national surveillance systems in existence, providing a model public health surveillance system for all types of exposures, public health event identification, resilience response and situational awareness tracking.

WARNING: Comparison of exposure or outcome data from previous AAPCC Annual Reports is problematic. In particular, the identification of fatalities (attribution of a death to the exposure) differed from pre-2006 Annual Reports (see Fatality Case Review – Methods). Poison center death cases are described as all cases resulting in death and those determined to be poison related fatalities. Likewise, Table 22 (Exposure Cases by Generic Category) since year 2006 restricts the breakdown including deaths to single-substance cases to improve precision and avoid misinterpretation.

Introduction

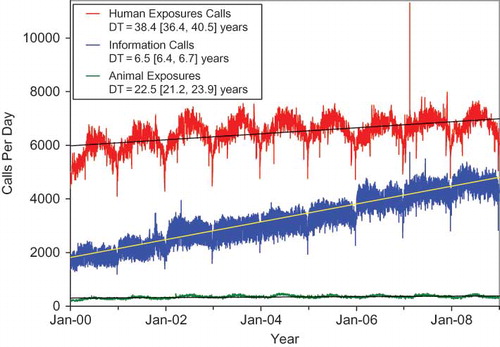

Sixty-one regional Poison Centers (PCs) serving the entire population of the 50 United States, American Samoa, District of Columbia, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands submit information calls and exposure case data collected during the course of providing patient tailored exposure management to callers. This data is compiled by the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC) into its National Poison Data System (NPDS). PCs place emphasis on exposure management, accurate data collection and coding, and the continuing need for poison related public and professional education. The centers' health care professionals are available free of charge to callers 24-hours a day every day of the year. PCs respond to questions from both the public and health care professionals. The continuous staff dedication at regional poison centers is manifest as the number of exposure and information calls continues to rise (). Calls to PCs either involve an exposed human or animal (EXPOSURE CALL) or a request for information (INFORMATION CALL) with no person or animal exposed to a substance.

Table 1A. Growth of the AAPCC population served and exposure reporting (1983–2008)

What's New in NPDS and the Annual Report

Several enhancements were made to the tables and figures in this 26th Annual Report. One of the goals of the writing team has been to remove inconsistencies and improve the reader's ability to clearly understand the data. Our first foray into this area was the new version of introduced with the 2006 Annual Report. This year corrections for clarity were made to the age labels in all tables. NPDS age values may only be integers. So one can not be age 5½ or 20½, they are either 5 or 20 respectively. All major age brackets were conformed to the following major categories: ≤ 5 years, 6–12 years, 13–19 years, ≥ 20 years, and unknown. Only the headers were changed for clarity, this did not effect how the data were summarized. As in previous years, the complete report with all tables has been included in the print and online versions of the report. To better assist readers and are also provided via separate electronic links in the internet version of this report.

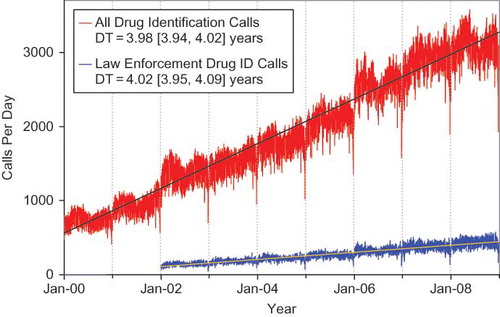

Linear least squares regression lines were added to the 5 call frequencies reported ( and ). Doubling times and confidence intervals (CI) provide a simple measure of relative rate of increase. The data array attached to shows the Mean ± SD [90% CI] by day of the week for each of the call types in and . The doubling time for human exposure calls was 38.4 [90% CI:36.4, 40.5] years compared to only 6.5 [90% CI:6.4, 6.7] years for information calls and 3.98 [90% CI: 3.94, 4.02] for all drug identification calls. Clearly the slope for drug identification calls is steeper than human exposures and all information calls. With the current economic crisis and associated impact on PC funding, some PCs have elected to terminate drug identification services. This clearly demonstrated ever increasing demand for drug identification assistance will need to be addressed as it impacts PC available resources and staffing. In addition, drug identification request data adds perspective on prescribing usage and diversion patterns.

Fig. 1. Human Exposure Calls, Information Calls and Animal Exposure Calls by Day since January 1, 2000.

Line shows least-squares linear regression, DT = doubling time from the slope of the linear regression of the log-calls/day and 90% confidence interval.

Fig. 2. Drug Identification and Law Enforcement Drug Identification Calls by Day since January 1, 2000.

Line shows least-squares linear regression, DT = doubling time from the slope of the linear regression of the log-calls/day and 90% confidence interval.

Fig. 3. Information Calls (total) for 2008 by Day of Week.

Means and SEM (diamonds) and SDs (horizontal lines) by Oneway ANOVA, F(6, 1) = 78.3, p<0.0001, Rsquare = 0.566, N = 366. Fewest calls (N = 2825) was Thursday December 25, 2008. Data array shows the Mean ± SD [90% confidence interval] by day of the week for each of the call types in and .

![Fig. 3. Information Calls (total) for 2008 by Day of Week.Means and SEM (diamonds) and SDs (horizontal lines) by Oneway ANOVA, F(6, 1) = 78.3, p<0.0001, Rsquare = 0.566, N = 366. Fewest calls (N = 2825) was Thursday December 25, 2008. Data array shows the Mean ± SD [90% confidence interval] by day of the week for each of the call types in Figures 1 and 2.](/cms/asset/4e656af1-ce39-4805-96ac-5721a33bec5f/ictx_a_444217_f0003_b.jpg)

and its associated table quantifies call rates by “day of week” for human and animal exposures, all information calls, and the subsets all drug identification and law enforcement only requests. All group patterns are statistically significant with the largest absolute volume decrease being all information calls for Saturdays and Sundays. presents a statistical/graphical summary for information calls. Detailed analyses of this type can be used to assist PCs to maintain optimal staffing. In this example, based on information calls alone, centers could down-staff for management of information calls on Saturdays and Sundays. Application of these techniques could help PCs save valuable budget dollars. Curiously, the fewest number of information calls was Christmas day.

Previous versions of , Comparisons of Death Data (1985–2008), mixed deaths associated with exposures and poison related fatalities as categorized by at least 3 different fatality scoring systems. Death case data was meticulously reviewed back to 1985 to establish that most years reported absolute counts of cases with medical outcomes of death or death, indirect report. now reports all years this way. We believe that this change will make it easier to compare absolute death counts from year to year. can still be created using the NPDS application and including the desired Relative Contribution to Fatality (RCF) score. There have been several positive changes to as well. A standardized set of alternate names and a standardized set of analyte names were created. Both names are lower case and uniformly applied throughout the table.

This year, lists human exposures with medical outcome of death or death, indirect report regardless of RCF score. Deaths that were pregnant have also been flagged to allow for rapid identification. The Fatality Review process continued with the new system introduced in 2007. However, the fatality case selection process for narrative publication excluded cases with medical outcome of death, indirect report. Two pediatrician medical toxicologist Fatality Reviewers volunteered to review exclusively the 53 pediatric deaths for 2008. This was undertaken to provide a more consistent and enhanced review of these important cases.

In 2008, numerous enhancements were introduced in the NPDS application. Many of these focused on surveillance and are detailed in the Surveillance section. Transcending all of the improvements were the two NPDS web services: aggregate case counts (total and human exposure call volumes, and clinical effects volume by geographical and time period of interest) and the full case information web service. These web services provide data to external systems or viewers to analyze NPDS data in ways not currently possible in the NPDS application. The aggregate web service provides total call volume, human exposure call volume, or clinical effects counts linked by AND or OR allowing an external system such as RODS (Real-time Outbreak and Disease Surveillance, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Biomedical Informatics) to create time-series. Unique to NPDS, the aggregate case count web service is not only accessible by external computer systems but also directly by system users to create their own time series without the need for external system software. The full case web service provides entire cases or portions of cases to authorized users. Queries for both web services may be done for any date range and for any time period of interest (down to the hour) and by Center, State or ZIP code. Time series technology was not an initial NPDS function but the web service allows for time series creation. The web services also allow for NPDS data to be provisioned in a federated manner where the data is always current in NPDS and can be readily accessed as needed without the need for costly cloning and warehousing.

The communications modules were also completed for the NPDS fatality and surveillance teams allowing for all correspondence to be stored within a fatality case or surveillance anomaly. Finally a new security model was introduced realizing the vision of the individual regional poison center controlling access to its data for its own users, sharing data with other centers, or allowing access to data by respective external organizations like State and local health departments.

Methods

Characterization of participating Poison Centers

All 61 participating centers submitted data to AAPCC for 2008. Fifty-eight centers (95%) were certified by AAPCC at the end of 2008. The entire population of the 50 states, American Samoa, the District of Columbia, Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands was served by PCs in 2008.

The average number of human exposure cases managed per day by all US poison centers was 6,825. Similar to other years, higher volumes were observed in the warmer months, with a mean of 6,121 cases per day in June compared with 5,073 per day in January. On average, ignoring the time of day and seasonal fluctuations, US PCs received one call concerning a suspected or actual human exposure every 12.7 seconds. The median time to upload data is 24 [7.2, 112] (median [25%, 75%]) minutes creating a real-time national exposure database and surveillance system.

Call management – specialized poison exposure emergency providers

Poison center operation as well as clinical education and instruction are directed by Managing Directors (most are PharmDs or RNs with American Board of Applied Toxicology [ABAT] board certification). Medical direction is provided by Medical Directors who are board-certified physician medical toxicologists. At some poison centers, the Managing and Medical Director positions are held by the same person.

Calls received at US PCs are managed by healthcare professionals who have received specialized training in toxicology and managing exposure emergencies. These providers include medical and clinical toxicologists, registered nurses, doctors of pharmacy, pharmacists, chemists, hazardous materials specialists, and epidemiologists. Specialists in Poison Information (SPIs) are primarily registered nurses, PharmDs, and pharmacists. They work under the supervision of a Certified Specialist in Poison Information (CSPI). SPIs must log a minimum of 2,000 calls over a 12 month period to become eligible to take the CSPI examination for specialists in poison information. Poison Information Providers (PIPs) are allied healthcare professionals. They manage information-type and low acuity (non-hospital) calls and work under the supervision of a CSPI. Of note is the fact that no nursing or pharmacy school offers a toxicology curriculum designed for poison center work and SPIs must be trained in programs offered by their respective PC.

NPDS – near real-time data capture

Launched on 12 April 2006, NPDS is the data repository for the 61 regional poison centers. In 2008, 60 of the 61 US PCs uploaded case data automatically to NPDS with one center uploading data periodically (beginning on 22 January 2009, all centers submitted data near real-time). The web-based NPDS software facilitates querying, reporting and a myriad of surveillance uses allowing AAPCC, its member centers and public health agencies to utilize US poisoning exposure data. Users are able to access local and regional data for their own areas and view national aggregate data. The application allows for increased “drill-down” capability and mapping via a geographic information system (GIS). Custom surveillance definitions are available along with ad hoc reporting tools. Information in the NPDS database is dynamic. Each year the database is locked prior to extraction of annual report data to prevent inadvertent changes and ensure consistent, reproducible reports. The 2008 database was locked on 9 October 2009 at 1905 hours EDT.

Annual report case inclusion criteria

The information in this report reflects only those cases that are not duplicates and classified as CLOSED. A case is closed when the PC has determined that no further follow-up/recommendations are required or no further information is available. Cases are followed as to precise a medical outcome as possible. Depending on the case specifics, most calls are “closed” within the first hours of the initial call. Some calls regarding complex hospitalized patients or cases resulting in death may remain open for weeks or months while data continues to be collected. Follow-up calls provide a proven mechanism for monitoring the appropriateness of management recommendations, augmenting patient guidelines and providing poison prevention education, enabling continual updates of case information as well as obtaining final/known medical outcome status to make the data collected as accurate and complete as possible.

NPDS surveillance

As previously noted, 60 of the 61 US PCs upload case data automatically to NPDS. This unique near real-time upload is the foundation of the NPDS surveillance system permitting both spatial and temporal case volume and case based surveillance. NPDS software allows creation of volume and case based definitions at will. Definitions can then be applied to national, regional, state, or ZIP code coverage areas. Geocentric definitions can also be created. This functionality is available not only to the AAPCC surveillance team, but to every regional poison center. PCs also have the ability to share NPDS real-time surveillance technology with external organizations such as their state and local health departments or other regulatory agencies. Another unique NPDS feature is the ability to generate system alerts on adverse drug events and other products of public health interest like contaminated food or product recalls. NPDS can thus provide real-time adverse event monitoring and surveillance for resilience response and situational awareness.

Surveillance definitions can be created to monitor a variety of volume parameters using a multiplicity of mathematical options with historical baseline periods from 1 to 8 years. Case based definitions for any desired substance or commercial product in the product database of over 350,000 entries are also available (Micromedex® Healthcare Series [Internet database]. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomson Reuters [Healthcare] Inc.). NPDS surveillance tools include:

Volume alerts

Total Call Volume

Human Exposure Call Volume

Clinical Effects Volume (signs and symptoms or laboratory abnormalities)

Case Based Surveillance Definitions

Substance

Clinical Effects

Various NPDS data fields

Boolean field expressions

Incoming data is monitored continuously and any anomalous signal detected generates an automated email alert to the AAPCC's surveillance team or designated regional PC or public health agency. These anomaly alerts are reviewed by the AAPCC surveillance team and/or the regional PC that created the surveillance definition. When reports of potential public health significance are detected, additional information is obtained via e-mail or phone from reporting PCs. The regional PC then alerts their respective affected state or local health departments. Public health issues are brought to the attention of the Health Studies Branch, Division of Environmental Hazards and Health Effects, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This unique near real-time trace back ability is a unique feature offered by NPDS and the regional PCs.

AAPCC Surveillance team toxicologists review surveillance definitions on a regular basis to fine-tune the queries. CDC as well as state and local health departments with NPDS access as granted by their respective regional poison centers also have the ability to create surveillance definitions to respond to emerging public health events.

Fatality case review

NPDS fatality cases can be recorded as either DEATH or DEATH, INDIRECT REPORT. Medical outcome of death is by direct report. A reported fatality is coded as “indirect” if the PC was, in most cases, not directly contacted by the medical team, coroner, or family member, or post mortem reports were sent by the coroner or medical examiner for PC review, or the PC summarized a news account. However, a coroner or medical examiner or family member calling the PC with a question about the cause of death or a family member requesting interpretation of a toxicology laboratory result from a case not previously discussed with the PC is coded as a Death rather than Death, indirect report.

Although poison centers may report DEATH as an outcome, the death may not be the direct result of the poisoning exposure. We define Poison-related fatality as a death that was judged by the Fatality Review Team to be at least contributory to the exposure.

During the year, each death case is abstracted by the reporting regional PC center and verified for accuracy. These cases are then systematically reviewed at year end by Fatality Case Review Teams (CRT). Each CRT consisted of the following members:

Author – the PC medical director or their designee responsible for the case data entered, the abstract, and the initial choices of RCF and Substances;

Lead Reviewer – Medical Director or Managing Director (assigned from a PC other than the center from which the individual case originated using pseudorandom numbers) to provide the primary review of the case;

Peer Reviewer – Managing Director (if the lead reviewer was a Medical Director) or Medical Director (if the lead reviewer was a Managing Director) assigned (using pseudorandom numbers) to provide the second (complementary) review of the case;

Manager – Louis Cantilena MD (east coast) or Daniel A. Spyker MD (west coast) assigned by PC ZIP code.

The fundamental classification for the NPDS fatalities reporting is whether the exposure caused the death. The review teams assessed the following parameters for each fatality case:

Relative contribution of the toxic exposure to the death, RCF (see grading system below);

Cause Rank of the substances involved as described below;

Abstract scoring (see scoring system below);

Degree of agreement between the Abstract and the NPDS database entries for that case;

Degree of agreement and if resolution was required between determinations made by members of the CRT.

Cause Rank is a separate field associated with each substance to address the circumstance where 2 or more substances were judged causative, but we lack evidence to distinguish between them. Cause Rank defaults to the same number as the Substance Rank, 1, 2, 3, . . . so it does not require additional data entry in the usual single substance or clear ranking circumstances. Changing Cause Rank permits assignment of equivalence in the event the reviewer cannot distinguish between causative substances, e.g., they may rank substances as 1, 1, 3 instead of 1,2,3 and so forth.

The primary basis of the case classification and abstract evaluations were the:

Clinical Case Evidence – includes a variety of information such as the data entered into NPDS and, when available, the medical examiner's report.

Medical Examiner's Report – the postmortem examination results, autopsy report or the coroner's report were always sought and, when available, became an important part of fatality case review.

Relative Contribution to Fatality

The definitions used for the Relative Contribution to Fatality (RCF) classification were as follows:

Undoubtedly responsible – In the opinion of the CRT the Clinical Case Evidence establishes beyond a reasonable doubt that the SUBSTANCES actually caused the death.

Probably responsible – In the opinion of the CRT the Clinical Case Evidence suggests that the SUBSTANCES caused the death, but some reasonable doubt remained.

Contributory – In the opinion of the CRT the Clinical Case Evidence establishes that the SUBSTANCES contributed to the death, but did not solely cause the death. That is, the SUBSTANCES alone would not have caused the death, but combined with other factors, were partially responsible for the death.

Probably not responsible – In the opinion of the CRT the Clinical Case Evidence establishes to a reasonable probability, but not conclusively, that the SUBSTANCES associated with the death did not cause the death

Clearly not responsible – In the opinion of the CRT the Clinical Case Evidence establishes beyond a reasonable doubt that the SUBSTANCES did not cause this death.

Unknown – In the opinion of the CRT the Clinical Case Evidence is insufficient to impute or refute a causative relationship for the SUBSTANCES in this death.

Review team procedure

A total of 14 review teams (28 individuals) volunteered to participate in the review. Reviewers were Medical Toxicologists (N = 15) or Clinical Toxicologists (N = 13). This year, a separate team of two Medical Toxicologists focused on the 53 pediatric fatalities. Names and affiliations of the reviewers are listed in Appendix A. Training and communication included weekly teleconferences, written guidance documents, spreadsheets (for assignment and reporting), the NPDS-Fatality Module (NPDS-FM) and individual telephone contacts. The initial 1,756 fatalities were randomly assigned such that each of the 28 individuals served as Lead Reviewer on 65–67 adult cases or 26–27 pediatric cases. Each individual peer reviewed another similar number of cases. For each fatality assigned, the Lead Reviewer:

Recorded their independent assessment of the RCF;

Recorded their assessment of the author's listing and ranking of the substance(s), and edited the case abstract as needed;

Scored the fatality case in regard to quality/completeness and novelty/educational value;

Evaluated the degree of agreement between the abstract and the NPDS database entries for that case;

Led the resolution of any questions with the CRT and Manager as required.

For each fatality assigned, the Peer Reviewer:

Recorded the agreement between the abstract and the NPDS database as described above for the Lead reviewer;

Reviewed the decisions of the Lead Reviewer (steps 1–4) and recorded their agreement with the Lead Reviewer.

Final decisions as to the fatality category and involved substances and sequence were derived from the Clinical Case Evidence. In most cases, the 3 members of the CRT were able to reach consensus. Decisions, which could not be resolved within the CRT, were queried to the responsible Manager for review and discussion.

Selection of abstracts for publication

The 89 abstracts included in Appendix C were selected for publication in a 3-stage process consisting of qualifying, ranking and reading. Qualifying was based on the RCF. Project reviewers recommended qualifying only RCF = 1, 2 or 3 (Undoubtedly Responsible, Probably Responsible or Contributory) as eligible for publication. Fatalities by Indirect report were not eligible for 2008. Qualifying cases thus numbered 1136. Ranking was based on the number of substances (33%) and weighted abstract scores (67%). The weightings were the averages chosen by the review team recommendations in 2006. Each was multiplied by the respective factors to obtain a weighted publication score: Hospital records * 4.4 + Postmortem * 7.6 + Blood levels * 6.9 + Quality/Completeness * 6.4 + Novelty/Educational value * 6.0.

The top ranked 200 abstracts were each read by 5 of the individual reviewers (Durback-Morris, Geller, Sangalli, Simone, Wiegand) and the 2 managers (Cantilena and Spyker). Each reader judged each abstract as “publish” or “omit” and all abstracts receiving 4 or more publish votes were selected, further edited and cross-reviewed by the 2 managers and a third writer (Rumack).

Results

2008 case summary

In 2008, the 61 participating PCs logged 4,333,012 total cases including 2,491,049 closed human exposure cases (), 130,495 animal exposures (), 1,703,762 information calls (), 7,336 human confirmed nonexposures, and 370 animal confirmed nonexposures. An additional 1,296 calls were still open at the time of database lock. The cumulative AAPCC database now contains close to 48.5 million human exposure case records (). A total of 11,333,063 information calls (as described below) have been logged by NPDS since the year 2000. shows the human exposures, information calls and animal exposures by day since 2000. Linear regression and the least squares regression lines were added to the call frequencies reported. All were highly statistically significant (p < 0.001, N = 3288). Regressions of the natural log of the same data permitted calculation of a doubling time = ln(2)/slope (just as is done to calculate a disappearance half-life). We report these doubling times and 90% confidence intervals as a measure of relative rate of increase. The 90% CI was chosen as it gives the 5% lower bound and 95% upper bound.

Table 1B. Non-human exposures by animal type

Table 1C. Distribution of information calls

PCs made 2,897,491 follow-up calls (or a series of calls) in 2008. Follow-up calls were done in 45.1% of human exposure cases. One follow-up call was made in 22.2% of human exposure cases, and multiple follow-up calls (range 2–128) were placed in 22.9% of cases.

Information calls to Poison Centers

Data from 1,703,762 information calls to PCs in 2008 () was transmitted to NPDS, including calls in optional reporting categories such as prevention/safety/education (36,804), administrative (27,727) and caller referral (64,081). Overall, the volume of information calls handled by US PCs increased by 6.3% over the 1,602,489 calls handled in 2007.Citation1

The most frequent information call was for drug identification, comprising 1,138,254 calls to PCs during the year (). Of these, 147,144 (12.9%) could not be identified over the telephone. We examined call rates for 2008 by “day of week” using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with day as a nominal variable. shows a graphical summary for information calls where ANOVA F(6, 1) = 78.3, p < 0.0001, Rsquare = 0.566, N = 366. The majority of the drug identification calls were received from the public, followed by law enforcement and health professionals. Most of the drug identification requests were regarding drugs sometimes involved in abuse; however, these cases were categorized based on the drug's abuse potential without knowledge of whether abuse was actually intended.

Drug information calls increased 30% from 2007 (177,436 calls) to 2008 (230,084 calls) and comprised 13.5% of all information request calls. Of these, the most common requests were in regards to therapeutic use and indications, followed by drug-drug interactions and questions about dosage. Environmental inquiries comprised 1.7% of all information calls. Of these environmental inquiries, questions related to cleanup of mercury thermometers were most common followed by questions involving pesticides.

Of all the information calls, poison information comprised 5.0% of the requests., with inquiries involving general toxicity the most common followed by questions involving food poisoning or food preparation practices and plant toxicity.

Exposure calls to poison centers

Tables 22A (Nonpharmaceuticals) and 22B (Pharmaceuticals) provide summary demographic data on patient age and gender, reason for exposure, medical outcome, and use of a health care facility for all 2,491,049 human exposure cases, presented by substance categories.

Column 1 (grey shading) lists the number of exposures to the substance in the total number of cases including multiple exposures (as in previous years) and is sorted in the table under the name of the substance ranked first by the regional PC. This column counts all exposures to that substance.

Column 2 (and the breakdowns by Age, Treatment Site, Reason, and Outcome) report single substance exposures only, i.e., excludes cases with a multiple substance exposure. Subtracting column 2 from column 1 provides the number of cases where there were multiple substance exposures.

and restrict the breakdown columns to single-substance cases to improve precision (avoid misrepresentation). Prior to 2007, when multi-substance exposures were included, a relatively innocuous substance was mentioned in a death column when, for example, the death was attributed to an antidepressant, opioid, or cyanide. This subtlety was not always appreciated by the uninformed user of the information. The restriction of the breakdowns to single-substance exposures should increase precision and reduce misrepresentation of the results in this unique by-substance table. Single substance cases reflect the majority (90.5%) of all exposures ().

and tabulate 2,858,250 substance-exposures mentions, of which 2,254,267 were single-substance exposures including 1,204,673 (53.4%) nonpharmaceuticals and 1,049,594 (46.6%) pharmaceuticals.

In 16.8% of exposures that involved pharmaceutical substances the reason for exposure was intentional, compared to only 2.9% when the exposure involved a nonpharmaceutical substance. Correspondingly, treatment in a health care facility was provided in a higher percentage of exposures that involved pharmaceutical substances (26.4%) compared with nonpharmaceutical substances (14.1%). Exposures to pharmaceuticals also had more severe outcomes. Of single-substance poison-related fatal cases, 350 were pharmaceuticals compared with 178 nonpharmaceuticals.

Age and gender distribution

The age and gender distribution of human poison exposure victims is outlined in . Children younger than 3 years were involved in 38.7% of exposures and children younger than 6 years accounted for half of all human exposures. A male predominance is found among recorded cases involving children younger than 13 years, but this gender distribution is reversed in teenagers and adults, with females comprising the majority of reported poison exposure victims.

Caller site and exposure site

As shown in , of the 2,491,049 human exposures reported, 76.0% of calls originated from a residence (own or other) but 93.4% actually occurred at a residence (Own or Other). Another 16.1% of calls were made from a health care facility. Exposures occurred in the workplace in 1.75% of cases, schools (1.3%), health care facilities (0.3%), and restaurants or food services (0.3%).

Table 2. Site of call and site of exposure, human exposure cases

Exposures in pregnancy

Exposure during pregnancy occurred in 8,477 women (0.34% of all human exposures). Of those with known pregnancy duration (n = 7,817), 31.4% occurred in the first trimester, 37.6% in the second trimester, and 31.0% in the third trimester. Most (72.6%) were unintentional exposures and 20.4% were intentional exposures.

Multiple patients

In 2008, 9.7% (241,258) of human exposures involved multiple patients. Examples of these include siblings sharing found medication, multiple victims of carbon monoxide exposure such as a family, or multiple patients inhaling vapors at a hazardous material spill.

Chronicity

The overwhelming majority of human exposures, 2,261,862 (90.8%) were acute cases (single, repeated or continuous exposure occurring over 8 hours or less) compared to 830 acute cases of 1,756 fatalities (47.3%). Chronic exposures (continuous or repeated exposures occurring over > 8 hours) comprised 1.9% (46,917) of all human exposures. Acute-on-chronic exposures (single exposure that was preceded by a continuous, repeated, or intermittent exposure occurring over a period greater than eight hours) numbered 158,490 (6.4%).

Reason for exposure

Most (82.8%) poison exposures were unintentional; suicidal intent was suspected in 8.7% of cases (). Therapeutic errors accounted for 10.6% of exposures (263,942 cases), with unintentional misuse comprising 4.3% of exposures. Of the 263,942 therapeutic errors, the most common scenarios for all ages included: inadvertent double-dosing in 84,814 (34.0%) cases, wrong medication taken or give (15.3%), other incorrect dose (14.8%), doses given/taken too close together (9.5%) and inadvertent exposure to someone else's medication (9.4%). The types of therapeutic errors observed are different for each age group and are summarized in .

Table 3. Age and gender distribution of human exposures

Table 5. Number of substances involved in human exposure cases

Table 6A. Reason for human exposure cases

Table 6B. Scenarios for therapeutic errors by age

The reason for most exposures was unintentional (82.8%) of all PC calls. Unintentional exposures outnumbered intentional poisonings in all age groups with the exception of age 13–19 years (). Intentional exposures were reported as frequently as unintentional exposures in patients age 13–19 years. In contrast, of the 1,315 of the reported human poisoning fatalities, the majority of the fatalities in children less than or equal to age 5 years was unintentional while most fatalities in adults (≥ 20 years) were intentional ().

Table 7. Distribution of reason for exposure by age

Route of exposure

Ingestion was the route of exposure in 79.3% of cases (), followed in frequency by dermal (7.2%), inhalation/nasal (5.2%), and ocular routes (4.5%). For the 1,315 fatalities, ingestion (77.7%), inhalation/nasal (7.8%), and parenteral (3.6%) were the predominant exposure routes.

Table 9. Route of exposure for human exposure cases

Clinical effects

The AAPCC database allows for the coding of up to 131 different clinical effects (signs, symptoms, or laboratory abnormalities) for each case. Each clinical effect can be further defined as related, not related, or unknown if related. Clinical effects were coded in 707,555 (28.4%) cases. (14.9% had 1 effect, 7.5% had 2 effects, 3.7% had 3 effects, 1.3% had 4 effects, 0.5% had 5 effects, and 0.5% had >5 effects coded). Of clinical effects coded, 79.2% were deemed related to the exposure(s), 9.2% were considered not related, and 11.6% were coded as unknown if related.

The duration of effect is required for all cases that report at least one clinical effect and have a medical outcome of minor, moderate or major effect (n = 493,386). demonstrates an increasing duration of the clinical effects observed with more severe outcomes.

Case management site

The majority of cases reported to PCs were managed in a non–health care facility (72.6%), usually at the site of exposure, primarily the patient's own residence (). Another 1.8% of cases were referred to a health care facility but refused to go. Treatment in a health care facility was rendered in 24.0% of cases.

Table 10. Management site of human exposures

Of the 598,048 cases managed in a health care facility, 295,834 (49.5%) were treated and released without admission, 93,096 (15.6%) were admitted for critical care, and 55,878 (9.3%) were admitted for noncritical care.

The percentage of patients treated in a health care facility varied considerably with age. Only 9.9% of children younger 5 years or younger and only 11.1% of children between 6 and 12 years were managed in a health care facility compared with 42.8% of teenagers (13–19 y) and 35.8% of adults (age ≥20 y).

Medical outcome

displays the medical outcome of the human poison exposure cases distributed by age, showing a greater incidence of severe outcomes in the older age groups. compares medical outcome and reason for exposure and shows a greater frequency of serious outcomes in intentional exposures.

Table 11. Medical outcome of human exposure cases by patient age

Table 12. Medical outcome by reason for exposure in human exposures

Decontamination procedures and specific antidotes

and outline the use of decontamination procedures, specific antidotes, and measures to enhance elimination in the treatment of patients reported in this database. These must be interpreted as minimum frequencies because of the limitations of telephone data gathering.

Table 13. Duration of clinical effects by medical outcome

Table 14. Decontamination and therapeutic interventions

Table 15. Therapy provided in human exposures by age

demonstrates the continuing decline in the use of ipecac-induced emesis in the treatment of poisoning. Ipecac was administered in only 641 (<0.01%) pediatric human poison exposures in 2008. The continued decrease in ipecac syrup use in the last decade was likely a result of ipecac use guidelines issued in 1997 by the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology; European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists and updated in 2004.Citation2,Citation3 In a separate report, the American Academy of Pediatrics concluded not only that ipecac should no longer be used routinely as a home treatment strategy, but also recommended disposal of ipecac currently in homes.Citation4

Table 16. Decontamination trends (1985–2008)

Top substances in human exposures

presents the most common 25 substance categories involved in human exposures, listed by frequency of exposure. and present similar data for children and adults, respectively, and show the differences between pediatric and adult poison exposures.

Table 17A. Substance categories most frequently involved in human exposures (Top 25)

Table 17B. Substance categories most frequently involved in pediatric (≤ 5 y) exposures (Top 25)

Table 17C. Substance categories most frequently involved in adult (≥20 y) exposures (Top 25)

Distribution of suicides

shows the modest variation in the distribution of suicides over the past 2 decades as reported to the NPDS's national database (45–68%). Since 1985, the percent of fatal cases has increased from 0.036% to 0.070% and the percent of pediatric cases has decreased from 6.1% to 2.2%. (See ).

Table 18. Categories associated with largest number of fatalities (Top 25)

Table 19. Comparisons of death data (1985–2008)

Plant exposures

provides a summary of plant exposures for those species and categories most commonly involved (top 25 of 63,362 total plant exposures). The top three table categories are essentially synonymous for unknown plant and comprise 14.1% (8,918/63,362) or all plant exposures. For a variety of reasons it was not possible to make a precise identification in these three groups. The top five most frequent plant exposures where a positive plant identification was made were descending order): Spathiphyllum species, Phytolacca americana (L.) – pokeweed, Euphorbia pulcherrima (Wild)), Philodendron (Species unspecified), and Toxicodendron radicans (L.).

Table 20. Frequency of plant exposures (Top 25)

Deaths and poison-related fatalities

A listing of cases () and summary of cases (, , , and ) are provided for fatal cases for which there exists reasonable confidence that the death was a result of that exposure. Of the 1,769 cases initially referred, 13 were miscoded (animal death, not a death, or not primary center). Of the 1756 finally classified, the CRT judged 1,315 poison related fatalities (RCF category = 1-Undoubtedly responsible, 2-Probably responsible, or 3-Contributory). The remaining 441 cases were judged as follows: 91 as RCF = 4-Probably not responsible, 57 as 5-Clearly not responsible, and 293 as RCF = 6-Unknown.

Table 21. Listing of fatal nonpharmaceutical and pharmaceutical exposures (this table can be viewed separately online at www.informahealthcare.com/ctx)

Deaths are sorted in this listing according to the category, patient age and substance deemed most likely responsible for the death. Please note: the Substance listed in column 3 of was chosen to be the most specific based upon all of the clinical information including the substances entered for that case. This substance may not agree with the categories used in the summary tables (including ). Additional agents implicated are listed below the primary agent in the order of their contribution to the fatality. The exposure-related fatalities involved a single substance in 528 cases (40.2%), 2 substances in 316 cases (24.0%), 3 in 220 cases (16.7%), and 4 or more in the balance of the cases. The cross-references at the end of each major category section list all cases that identify this substance as other than the primary substance.

Table 22A. Demographic profile of SINGLE-SUBSTANCE nonpharmaceuticals exposure cases by generic category (this table can be viewed separately online at www.informahealthcare.com/ctx)

Table 22B. Demographic profile of SINGLE-SUBSTANCE pharmaceuticals exposure cases by generic category (this table can be viewed separately online at www.informahealthcare.com/ctx)

The Case number is [bracketed] to indicate that the abstract for that case is included in Appendix C. The letters following the Case number include: i = reported to poison center indirectly (by coroner, medical examiner, or other) after the fatality occurred in 179 cases (13.6%), p = prehospital cardiac and/or respiratory arrest in 567 (43.1%), h = hospital records reviewed in 176 cases (143.4%), a = autopsy report reviewed in 359 cases (27.3%).

The distribution of RCF is as follows: 1 = Undoubtedly responsible in 670 cases (50.1%), 2 = Probably responsible in 466 cases (35.4%), 3 = Contributory in 179 cases (13.6%).

All fatalities – all ages

presents the age and gender distribution for these 1,315 poison-related fatalities. The age distribution of reported fatalities is similar to that in past years with 74.8% (983 of 1,315) of fatal cases occurring in adults (age > 19 years) (). Although children younger than 6 years were involved in the majority of exposures, they comprised just 2.0% of the exposure-related fatalities. Most (76.2%) of the poisoning fatalities occurred in 20-to 59-year-old individuals.

lists each of the 1,315 human fatalities along with all of the substances involved. Please note: the Substance listed in column 3 of was chosen to be the most specific generic name based upon the substances entered for that case. This substance may not agree with the categories used in the summary tables (including ).

lists the top 25 substance categories associated with reported fatalities and the number of single exposure fatalities for that category – sedative/hypnotics/antipsychotics, opioids, and antidepressants lead this list followed by cardiovascular drugs, acetaminophen in combination, alcohols, and stimulants/street drugs. Although sedative/hypnotics/antipsychotics ranks 4th and antidepressants 7th among the most frequent exposures (), there is otherwise little concordance between the frequency of exposures to a substance and the number of fatalities. Note that this Table tabulates all substances to which a patient was exposed (i.e., a patient exposed to an opioid may have also been exposed to 1 or more other products).

A single substance was implicated in 90.5% of reported human exposures, and 9.5% of patients were exposed to 2 or more drugs or products (). The exposure-related fatalities () involved a single substance in 528 cases (40.2%) and 2 or more substances in 787 cases (59.8%). The first ranked substance was a pharmaceutical in 1,066 of the 1,315 fatalities (81.2%). These 1,066 pharmaceuticals included (first ranked substance):

544 analgesics (110 acetaminophen, 73 acetaminophen/ hydrocodone, 71 methadone, 62 oxycodone, 48 salicylate, 34 morphine, 32 fentanyl transdermal, 25 acetaminophen/diphenhydramine, 16 acetaminophen/oxycodone, 15 acetaminophen/propoxyphene)

113 cardiovascular drugs (17 verapamil, 15 cardiac glycoside, 13 beta blockers, 12 diltiazem (extended release), 8 metoprolol, and 6 amlodipine)

111 antidepressants (16 amitriptyline, 13 lithium, 10 bupropion, 11,)

87 stimulants/street drugs (45 cocaine, 16 heroin, 8 amphetamine, 8 methamphetamine, and 6 MDMA)

The exposure was acute in 692 (52.6%), A/C = acute on chronic in 241 (18.3%), C = chronic exposure in 87 (6.6%) and U = unknown in 295 (22.4%).

Tissue Concentrations for 1 or more related analytes were reported in 597 cases (45.4%).

Route of exposure was: Ingestion in 1,101 cases (77.7%), Inhalation/nasal in 110 cases (7.8%), Parenteral in 51 cases (3.6%). ()

Intentional exposure reasons: Suspected suicide in 663 cases (50.4%), Intentional-Abuse in 229 cases (17.4%), Intentional-Misuse in 39 cases (3.0%). Unintentional exposure reasons: Environmental in 41 cases (3.1%), Therapeutic error in 36 cases (2.7%), Misuse in 10 cases 0.8%). ()

Pediatric fatalities – age less than 6 years

Although children younger than 6 years were involved in the majority of exposures, they comprised just 34 of 1,315 (2.0%) of fatalities. These numbers are similar to those reported since 1985 (). The percentage fatalities in children younger than 6 years related to total pediatric exposures was 26/1,292,754 = 0.00201%. By comparison, 1,201/856,908 = 0.140% of all adult exposures involved a fatality. Of these 26, 17 (65.4%) were reported as unintentional and 3 (11.5%) were coded as resulting from malicious intent (). These 26 cases included 16 pharmaceuticals and 10 nonpharmaceuticals. The substances associated with these fatalities included: carbon monoxide/smoke inhalation (4 cases), oxycodone (3 cases), sodium bicarbonate (2 cases) and 17 other substances (1 each).

Pediatric fatalities – ages 6–12 years

In the age range 6 to 12 years, there were 8 reported fatalities (), 4 of which were unintentional exposures and 2 intentional exposures. These 12 cases included 3 pharmaceuticals and 5 nonpharmaceuticals. The substances associated with these fatalities included: carbon monoxide/smoke inhalation (3 cases), bupropion, methadone, tramadol, hair spray and paraquat (1 each).

Adolescent fatalities – ages 13–19 years

In the age range 13 to 19 years, there were 74 reported fatalities (). These 74 cases included 60 pharmaceuticals and 14 nonpharmaceuticals, similar to the numbers reported in this age group reported annually since 1999. The first ranked pharmaceuticals associated with these fatalities included: methadone and oxycodone (6 cases each), acetaminophen, bupropion and quetiapine (4 each), acetaminophen/oxycodone, MDMA, opioid, and salicylate (3 each), and amphetamine, and lithium (2 each) and 26 other substances (1 each).

Of the 74 reported fatalities for adolescents, 28 (37.8%) were presumed suicides, and 26 (35.1%) were intentional abuse exposures (). The suspected suicide percentage is similar to recent years. The percentage of intentional abuse cases increased from 25.8% in 2006 to 35.7% in 2008. As in the past years, only a small number (8 of 74) of adolescent fatalities were coded as being unintentional.

Pregnancy and fatalities

A total of 26 deaths of pregnant women have been reported from the years 2000 through 2008. An average of 2 deaths per year was recorded from 2000 through 2004. Since 2005, the average number of deaths in pregnant women reported to NPDS doubled to four per year. The majority (20 of 26) were intentional exposures of misuse, abuse and suspected suicide. These deaths are flagged in as of this year's report.

AAPCC surveillance system

NPDS surveillance processes, anomaly definitions, and application software continue to be developed, refined, and evaluated. Surveillance Anomaly 1 was generated at 2:00 pm EDT on September 17, 2006. This event marked the transition of AAPCC surveillance to NPDS. Since then more than 136,000 anomalies have been detected. Many individual PCs and CDC have created surveillance case definitions. Case definitions have been authored by many regional poison centers, the AAPCC, and Health Studies Branch, Division of Environmental Hazards and Health Effects, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The system has been expanded to include new case based definitions, and enhanced surveillance capabilities at the regional PC level. At the time of this report, 370 surveillance definitions run continuously, monitoring case and clinical effects volume and a variety of case based definitions from food poisoning to nerve agents.

Significant NPDS surveillance enhancements were introduced in 2008. Geocentric coverage was added to the volume definitions allowing centers to create definitions for all cases from their geographic coverage area, not just cases taken by their center. Case based definitions were improved with the addition of expanded Boolean expression size to allow more complex case based surveillance definitions to be created. Clinical effect anomaly analysis screen was optimized to allow for analysis per clinical effect. Increased definition creation flexibility was added to volume definitions. This flexibility included the ability to extend active definitions beyond their original expiration date. Anomaly alert email information was expanded to make the alert information richer and definition alerts could be chosen for one-time alerts to give the user the option to use the NPDS surveillance engine as a notification system to detect cases for study rather than a surveillance system. Six new surveillance reports and logging reports were added to the application to allow the user to search for definitions based on a variety of parameters in order to find a definition that pertains to certain characteristics of interest. A communications module was built into NPDS surveillance simplifying the process to store all analysis actions and correspondence with each anomaly.

NPDS implemented an aggregate count web service that allows users to extract case counts based on user defined parameters such as clinical effects and generate time series graphs for analysis. A second web service was added to allow external systems such as BioSense, RODS, ESSENCE, or state based system to extract NPDS data for the purpose of using NPDS full case data with their own surveillance engines and algorithms. Thus external system viewers can be used to augment existing NPDS analysis tools in a federated approach transforming NPDS into a data utility with always the most current data available for analysis. The advent of the NPDS web services marked a new era in NPDS development direction with all external system access under the purview of the responsible regional PC.

External users may now be given NPDS surveillance access by a poison center. NPDS surveillance access is now controlled by each poison center through the NPDS application. A center may grant any user access to their data and they may limit that access by one or more state and/or by one or more ZIP code. Regional Poison Centers remain completely in control of all access to their poison center data from a surveillance perspective.

Each surveillance definition now has a defined organization (owner) who is responsible for monitoring and analyzing the anomalies detected by the definition. NPDS now supports Full and Basic surveillance access. Basic access allows a user to survey the granting organization's data through the creating of surveillance definitions. Full access allows a user to view all definitions and anomalies owned by the granting organization and it allows the user to survey the granting organization's data by creating their own definitions. NPDS provided new functionality to allow user's to update and maintain his/her contact information used for surveillance notifications from NPDS. Surveillance storage was expanded to manage this additional data.

Automated surveillance remains controversial as a system to detect the index case of a public health event. Uniform evaluation algorithms are not available to determine the best and optimize methodologies.Citation5 Less controversial is the benefit to situational awareness that NPDS can provide. Typical NPDS surveillance data detects a response to an event rather than event prediction. The pre-recall tomato cases of the 2008 Tomato recall (see below) demonstrated the potential predictive value of NPDS as described using internet search engines. Recent work from several institutions has focused on the concept that queries to on-line information systems can predict major outbreaks.Citation6,Citation7 Analysis of PC calls analogous to internet search queries may provide predictive data for events of public health significance.

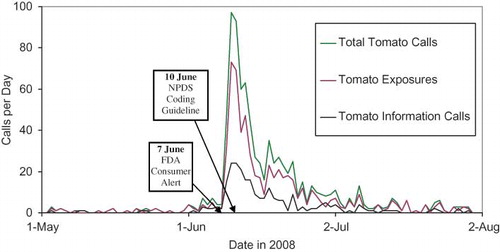

On June 7, 2008, FDA released an alert warning consumers not to eat certain types of raw red tomatoes. Possibly contaminated with Salmonella Saintpaul, an uncommon type of the bacteria.Citation8 Since mid-April 2008, 145 cases if salmonellosis had been reported nationwide. AAPCC issued a tomato recall coding guideline to poison centers on 10 June 2008. A retrospective review of NPDS tomato information calls and exposure calls revealed that prior to the FDA recall, daily calls to poison centers ranged from 0 to 2 calls per day. Beginning on 1 June 2008, calls increased ranging from 1 to 7 per day until 9 June when total tomato calls increased to 46 before peaking on 10–11 June at over 90 calls per day (). Clearly, the initial rise of tomato related calls occurred prior to the FDA release and before the coding guidelines were released to the centers. This marks the first time that such phenomena in NPDS data has been seen although it has been shown in other Internet information systems.Citation9 Food recalls are becoming more common. It is possible that augmenting NPDS with automated time series technology for common food products may provide useful data on outbreaks before they reach mainstream media. Although NPDS did not detect the index case, implementation of refined algorithms and close work with public health agencies shows NPDS promise as part of an early detection system. NPDS case data clearly presaged the FDA alert and the tomato information and exposure call patterns provided situational awareness about the event ().

Discussion

Trends in reported poisonings/exposures

The total of 4,333,012 human exposure cases and information calls reported to PCs in 2008 does not reflect the full extent of poison center efforts which also include activities such as poison prevention and education and poison awareness. Additionally, we do not know the true denominator for exposures and information calls in the United States.

These data () do not directly identify a trend in the overall incidence of poisonings in the US because the percentage of actual exposures and poisonings reported to PCs is unknown. As is explained in this section, NPDS data reports fewer fatalities and more exposures than other CDC databases.

NPDS may be considered as providing “numerator data” since the “denominator” is not accurately determined. Attempts have been made to better define the incidence of poisoning. For example, based on the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), the estimated number of poisoning episodes in the US for the year 2000 was estimated to be 1,575,000.Citation10 During the same time AAPCC centers received reports of 2.2 million poisoning exposures of which 475,079 were managed in a health care facility.Citation1

The frequency of any injury rests on the definition used. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) defined a poisoning as the “event resulting from ingestion of or contact with harmful substances including overdoses or incorrect use of any drug or medication.”Citation11 NCHS reported that the age-adjusted death rate for poisoning doubled from 1985 through 2004 to 10.3 deaths per 100,000 population. The rise was most evident from 1998 to 2000 when the poison fatalities increased an average of 8.2% per year.Citation11

The CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control latest poison data available are for the year 2006.Citation12 Their system reports 37,286 deaths from a US population of 298,362,973 and produces an age adjusted rate of 12.37 per 100,000 population [ICD-10 codes: X40-X49,X60-X69,X85-X90,Y10-Y19, Y35.2, *U01(0.6, 0.7)].Citation12 This is in contrast to the 1,229 fatalities captured by NPDS during this time period.Citation1

In 2005 (latest CDC report for this comparative data), 23,618 (72%) of the 32,691 poisoning deaths in the United States were unintentional, and 3,240 (10%) were of undetermined intent.Citation13 Unintentional poisoning death rates have been rising steadily since 1992. NPDS reported 2,005,307 unintentional exposures out of 2,403,539 total exposures reported. Unintentional poisoning was second only to motor vehicle crashes as a cause of unintentional injury death in 2005.Citation13 Among people 35–54 years old, unintentional poisoning caused more deaths than motor vehicle crashes. In the United States in 2005, 5,833 (18%) of the 32,691 poisoning deaths were intentional; 5,744 were suicides and 89 were homicides.Citation13 NPDS reported 308,483 intentional exposures for 2005.

Supplementary Material

Download MS Word (5.2 MB)Supplementary Material

Download MS Word (3.1 MB)References

- Previous year’s reports of the American Association of Poison Control Centers are available on the AAPCC website at http://aapcc.org/annual.htm.

- Position statement: ipecac syrup. American Academy of Clinical Toxicology; European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1997;35:699–709.

- American Academy of Clinical Toxicology European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists. Position Paper: Ipecac Syrup. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 2004; 42: 133–143.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Policy Statement. Poison treatment in the home. Pediatrics 2003;112:1182–1185.

- Sosin DM, DeThomasis J. Evaluation challenges for syndromic surveillance–making incremental progress. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53 Suppl:125–129.

- Ginsberg J, Mohebbi MH, Patel RS, Brammer L, Smolinske MS, Brilliant L. Detecting influenza epidemics using search engine query data. Nature. 2009;457:1012–1014.

- Polgreen PM, Chen Y, Pennock DM, Nelson FD. Using internet searches for influenza surveillance. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1443–1448.

- FDA. (2008, June 7). FDA Warns Consumers Nationwide Not to Eat Certain Types of Raw Red Tomatoes. Retrieved from http://www. fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2008/ucm116908. htm.

- Ginsberg1 J, Mohebbi1 MH, Patel1 RS, Brammer L, Smolinske MS, Brilliant L Detecting influenza epidemics using search engine query data. Nature 2009; 457: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature07634.

- IOM. Forging a Poison Prevention and Control System/Committee on Poison Prevention and Control, B Geyer, JA Alexander, P Blanc, D Emerson, JR Hedges, MS Kamlet, A Mickalide, BH Rumack, DP Schor, DA Spyker, A Stergachis, DJ Tollerud, DK Walker; Board on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2004 http://www.nap.edu/catalog/10971. html.

- Bergen G, Chen LH, Warner M, Fingerhut LA. Injury in the United States: 2007 Chartbook. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2008.

- WISQARS (Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System) accessed October 10, 2009 http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate10_sy.html.

- CDC: Poisoning in the United States: Fact Sheet http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/factsheets/poisoning.htm. Accessed 10 October, 2009.

- McGraw-Hill’s AccessMedicine, Laboratory Values of Clinical Importance (Appendix), Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. McGraw-Hill Professional, 2004, http://www.accessmedicine.com/. Accessed 24 June, 2008.

- Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies, Eighth Edition, McGraw-Hill Companies, 2006.

- Dart RC, editor. Medical Toxicology, Third Edition. Philadelphia, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2004.

Disclaimer

The American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC; http://www.aapcc.org) maintains the national database of information logged by the country's 61 Poison Centers (PCs) serving all 50 United States, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia. Case records in this database are from self-reported calls: they reflect only information provided when the public or healthcare professionals report an actual or potential exposure to a substance (e.g., an ingestion, inhalation, or topical exposure, etc.), or request information/educational materials. Exposures do not necessarily represent a poisoning or overdose. The AAPCC is not able to completely verify the accuracy of every report made to member centers. Additional exposures may go unreported to PCs and data referenced from the AAPCC should not be construed to represent the complete incidence of national exposures to any substance(s).

Appendix A – Acknowledgments

The compilation of the data presented in this report was supported in part through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control AAPCC Contract 200-2007-19121.

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Jim Hirt, AAPCC Executive Director and the staff at the AAPCC Central Office for their support during the preparation of the manuscript.

The authors wish to express their appreciation to the following individuals who assisted in the preparation of the manuscript: Lily H. Gong; Kathy Worthen; Laura Rivers; Carol Hesse, Mary Anne Stigall.

Poison Centers

We gratefully acknowledge the extensive contributions of each participating poison center and the assistance of the many health care providers who provided comprehensive data to the poison centers for inclusion in this database. We especially acknowledge the dedicated efforts of the Specialists in Poison Information (SPIs) who meticulously coded 4,333,012 calls made to U.S. Poison Centers in 2008.

The initial review of reported fatalities and development of the abstracts was the responsibility of the staff of the participating poison centers. These poison centers and individuals are listed at the beginning of this report.

Many individuals at each center participate in the review of their centers fatality cases. The following toxicology professionals summarized and prepared their center's fatality data for NPDS:

Alabama Poison Center

Perry Lovely, MD, ACMT

John Fisher, PharmD, DABAT, FAACT

Lois Dorough BSN, RN, CSPI

Arizona Poison and Drug Information Center

Jude McNally RPh, DABAT

Leslie Boyer MD, FACMT

Arkansas Poison & Drug Information Center

Henry F. Simmons, Jr., MD

Pamala R. Rossi, PharmD

Howell Foster, PharmD

Banner Good Samaritan Poison and Drug Information Center

Frank LoVecchio, DO, MPH

Steven C. Curry, MD

Kathleen Waszolek, RN, CSPI

Blue Ridge Poison Center

Christopher Holstege, MD

Nathan Charlton, MD

David Lawrence, MD

Brigid Wonderly, RN

Stephen Dobmeier, RN

California Poison Control System – Fresno/Madera Division

Richard J. Geller, MD, MPH

California Poison Control System – Sacramento Division

Timothy Albertson, MD, PhD

Judith Alsop, PharmD

California Poison Control System – San Diego Division

Richard F. Clark, MD

Lee Cantrell, PharmD

Shaun Carstairs, MD

Sean Nordt, MD, PharmD

Allyson Kreshak, MD

Alicia Minns, MD

Alex Miller, MD

California Poison Control System – San Francisco

Kent R. Olson, MD

Thanjira Jiranantakan, MD

Thomas E. Kearney, PharmD

Tanya Mamantov, MD

Craig Smollin, MD

Carolinas Poison Center

Michael C. Beuhler, MD

Jennifer Englund, MD

Marsha Ford, MD

William Kerns II, MD

Anna Rouse Dulaney, PharmD

Ashley Webb, MSc, PharmD

Central Ohio Poison Center

Marcel J. Casavant, MD, FACEP, FACMT

Heath Jolliff, DO, FACEP, FAAEM

S. David Baker, PharmD, DABAT

Julee Fuller-Pyle

Julie Lecky, BA

Central Texas Poison Center

Ron Kirschner, MD

Douglas J. Borys, PharmD

Children's Hospital of MI Regional Poison Center

Cynthia Aaron, MD

Lydia Baltarowich, MD

Keenan Bora, MD

Bram Dolcourt, MD

Matthew Hedge, MD, ACMT

Susan C. Smolinske, PharmD

Suzanne R. White, MD

Cincinnati Drug and Poison Information Center

G. Randall Bond, MD

Rachel Sweeney, RN

Connecticut Poison Center

Charles McKay, MD

Kevin O'Toole, MD

Jarret Lefberg, DO

Bernard C. Sangalli, MS

DeVos Children's Hospital Regional Poison Center

Bernard Eisenga PhD, MD

Bryan Judge, MD

Brad Riley, MD

Florida/USVI Poison Information Center – Jacksonville

Thomas Kunisaki, MD, FACEP, ACMT

Florida Poison Information Center – Miami

Jeffrey N. Bernstein, MD

Richard S. Weisman, PharmD

Florida Poison Information Center – Tampa

Cynthia R. Lewis-Younger, MD, MPH

Pam Eubank, RN, CSPI

Judy Gussett, RN, CSPI

Judy Turner, RN, CSPI

Georgia Poison Center

Robert Geller, MD

Brent W. Morgan, MD

Arthur Chang, MD

Ziad Kazzi, MD

Gaylord P. Lopez, PharmD

Richard Kleiman, MD

Carl Skinner, MD

Andre Matthews, MD

Hennepin Regional Poison Center

David J. Roberts MD, ABMT, ABMS

Elisabeth F. Bilden MD

Deborah L. Anderson PharmD

Samuel J. Stellpflug, MD

Illinois Poison Center

Michael Wahl, MD

Sean Bryant, MD

Indiana Poison Center

James B. Mowry, PharmD

R. Brent Furbee, MD

Iowa Statewide Poison Control Center

Edward Bottei, MD

Kentucky Regional Poison Center

George M. Bosse, MD

Henry A. Spiller, MS, RN

Long Island Regional Poison and Drug Information Center

Thomas R. Caraccio, PharmD, DABAT

Michael McGuigan, MDCM, MBA

Louisiana Poison Center

Thomas Arnold, MD

Mark Ryan, RPh

Maryland Poison Center

Suzanne Doyon, MD, FACMT

Patrick Dougherty, PharmD

Mississippi Regional Poison Control Center

Robert Cox MD, PhD, DABT, FACMT

Tanya Calcott, RN, CSPI

Missouri Regional Poison Center at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children's Medical Center

Anthony Scalzo, MD

Shelly Enders, PharmD, CSPI

National Capital Poison Center

Cathleen Clancy, MD, FACMT

Nicole Whitaker, RN, BA, BSN, MEd, CSPI

Nebraska Regional Poison Center

Claudia Barthold, MD

New Jersey Poison Information and Education System

John Kashani, DO

Steven M. Marcus, MD

New Mexico Poison and Drug Information Center

Steven A. Seifert, MD, FAACT, FACMT

New York City Poison Control Center

Maria Mercurio-Zappala, MS, RPh

Robert S. Hoffman, MD

Lewis Nelson, MD

Alex Manini, MD

Silas Smith, MD

Oladapo Odujebe, MD

Jen Prosser, MD

Brenna Farmer, MD

Samara Soghoian, MD

North Texas Poison Center

Brett Roth MD, ACMT, FACMT

Northern Ohio Poison Center

Susan Scruton, RN, CSPI

Lawrence S. Quang, MD

Alfred Aleguas, PharmD

Northern New England Poison Center

Theresa Maher, MFA

Tamas Peredy, MD

Oklahoma Poison Control Center

William Banner, Jr., MD, PhD, ABMT

Lee McGoodwin, PharmD, MS, DABAT

Oregon Poison Center

Zane Horowitz, MD

Sandra L. Giffin, RN, MS

Palmetto Poison Center

William H. Richardson, MD

Jill E. Michels, PharmD

Pittsburgh Poison Center

Kenneth D. Katz, MD

Rita Mrvos, BSN

Edward P. Krenzelok, PharmD

Puerto Rico Poison Center

José Eric Díaz-Alcalá, MD

Regional Center for Poison Control and Prevention Serving Massachusetts and Rhode Island

Nadeem Al-Duaij, MD, MPH

Michele Burns Ewald, MD

Mathew George, MD

Katherine O'Donnell, MD

Regional Poison Control Center – Children's Hospital of Alabama

Diane Smith, RN, CSPI

Valoree Stanley, RN, CSPI

Erica Liebelt, MD, FACMT

Michele Nichols, MD

Rocky Mountain Poison & Drug Center

Carol L. Hesse, RN, CSPI

Alvin C. Bronstein, MD, FACEP, FACMT

Jennie A. Buchanan, MD

Ryan Chuang, MD

Jason Hoppe, DO

Sean H. Rhyee, MD, MPH

Shawn M. Varney, MD, FACEP

Shan Yin, MD, MPH

Amy Zosel, MD

Mary Anne Stigall

South Texas Poison Center

Douglas Cobb, RPh

Cynthia Abbott-Teter, PharmD

Miguel C. Fernandez, MD

George Layton, MD

C. Lizette Villarreal, MA

Southeast Texas Poison Center

Wayne R. Snodgrass, MD, PhD, ABMT

Jon D. Thompson, MS, DABAT

Jean L. Cleary, PharmD, CSPI

Tennessee Poison Center

John G. Benitez, MD, MPH

Saralyn Williams, MD

Donna Seger, MD

Texas Panhandle Poison Center

Shu Shum, MD

Jeanie E. Jaramillo, PharmD

The Poison Control Center at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

Allison A. Muller, PharmD

Kevin Osterhoudt, MD

The Ruth A. Lawrence Poison and Drug Information Center

Ruth A. Lawrence, MD

Norma Barton, BS Pharm, CSPI

University of Kansas Hospital Poison Control Center

Jennifer Lowry, MD

Tama Sawyer, PharmD

Upstate NY Poison Center

Jeanna M. Marraffa, PharmD

Jamie Nelsen, PharmD

Christine M. Stork, PharmD

Utah Poison Control Center

Martin Caravati, MD, MPH

Virginia Poison Center

Rutherfoord Rose, PharmD

Kirk Cumpston, DO

Washington Poison Center

William T. Hurley, MD, FACEP

David Serafin, CPIP

West Texas Regional Poison Center

John F. Haynes, Jr., MD

Leo Artalejo III, PharmD

Hector L. Rivera, RPh

West Virginia Poison Center

Lynn F. Durback-Morris RN, BSN, MBA, DABAT

Anthony F. Pizon, MD, ABMT

Western New York Poison Center

Prashant Joshi, MD

Wisconsin Poison Center

David D. Gummin, MD

Mark A. Kostic, MD

Cathy Smith, CSPI

Fatality review team

The Lead and Peer review of the 2008 fatalities was carried out by the 29 individuals listed here. The authors and the AAPCC wish to express our appreciation for their volunteerism, dedication, hard work, and good will in completing this task in a very limited time.

Ann-Jeannette Geib*, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School New Brunswick NJ

Bernard C. Sangalli*, MS, DABAT, Director, Connecticut Poison Center

Charles McKay, MD, Associate Medical Director, Connecticut Poison Control Center, University of Connecticut School of Medicine

David Gummin, MD, Wisconsin Poison Center, Milwaukee, WI

Dean Olsen, DO, New York City Poison Center Staff, New York, NY

Edward P. Krenzelok, PharmD, FAACT, DABAT, Director, Pittsburgh Poison Center

Elizabeth J. Scharman, PharmD, DABAT, BCPS, FAACT, Director West Virginia Poison Center

Frank LoVecchio, DO, Co-Medical Director, Banner Good Samaritan Poison and Drug Information Center, Phoenix, AZ

Heath Jolliff, DO, Central Ohio Poison Center, Columbus, Ohio

Henry Spiller*, MS, DABAT, FAACT Kentucky Regional Poison Center, Louisville, KY

Howell Foster, PharmD, DABAT, Arkansas Poison & Drug Information Center

Jen Hannum, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center, Winston-Salem, NC

Jennifer Lowry**, MD, Medical Director, Kansas Poison Center at the University of Kansas Hospital, Kansas City, MO

Jill E. Michels, PharmD, DABAT, Managing Director, Palmetto Poison Center, SC

Judith A. Alsop, PharmD, DABAT, California Poison Control System – Sacramento Division

Karen E. Simone, PharmD, DABAT, Director, Northern New England Poison Center, Maine Medical Center

Kathryn Meier, PharmD, DABAT, Senior Toxicology Management Specialist, California Poison Control System, San Francisco Division

Lewis Nelson, MD, New York City Poison Center, New York University School of Medicine

Luke Yip*, MD, FACMT, FACEM, FACEP, Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center, Denver CO

Lynn Durback-Morris*, RN, MBA, DABAT, CSPI, Supervisor of Operations, West Virginia Poison Center

Maria Mercurio-Zappala, RPh, MS, DABAT, FAACT Managing Director, NYC Poison Control Center

Mark Su, MD, FACEP, FACMT, Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, Director, Fellowship in Medical Toxicology, Department of Emergency Medicine, North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, NY

Richard J. Geller, MD, MPH, FACP, Medical and Managing Director, California Poison Control System, Fresno/Madera

Robert B. Palmer, PhD, DABAT, Toxicology Associates, Denver, CO; Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center, Denver, CO

S. David Baker, PharmD, DABAT, Managing Director, Central Ohio Poison Center

Steven M. Marcus**, MD, NJ Poison Information and Education System, Departments of Preventive Medicine and Community Health and Pediatrics, NJ Medical School, University of Medicine and Dentistry of NJ.

Timothy Wiegand*, MD. Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine, Maine Medical Center, and Associate Medical Director, Northern New England Poison Center, Portland, Maine

William T. Hurley, MD, Medical Director, Washington Poison Center

*These reviewers further volunteered to read the top ranked 200 abstracts and judged to publish or omit.

**These individuals reviewed the pediatric fatalities.

Surveillance team

Surveillance was carried out by a team of 10 medical and clinical toxicologists working across the country in a distributed system who provided daily monitoring of surveillance anomalies throughout 2008:

Alfred Aleguas, PharmD, DABAT

Alvin C. Bronstein, MD, FACEP, FACMT

Blaine (Jess) Benson, PharmD, DABAT

Douglas Borys, PharmD, DABAT

Henry A. Spiller, MS, DABAT, FAACT

Jeanna M. Marraffa, PharmD, DABAT

John Fisher, PharmD, DABAT, FAACT

Maria Mercurio-Zappala, RPH, MS, DABAT, FAACT

Richard G. Thomas, PharmD, DABAT

S. David Baker, PharmD, DABAT

Regional Poison Center (RPC) Fatality Awards

This year the AAPCC and the Fatality Review team recognized several Regional Poison Centers (RPCs) for their extra effort in a variety of categories reflected by their preparation of fatality reports and prompt responses to reviewer queries during the review process. The awards were presented at the September 2009, North Amercian Congress of Clinical Toxicology meeting in San Antonio, Texas:

First Center to Complete all Cases – Pittsburgh Poison Center, closed the last of their cases September 1, 2008

Highest Percentage with Autopsy Reports – Oklahoma Poison Control Center, 97.4% of 153 cases

Highest Overall Quality of Reports – Carolinas Poison Center, 5.38 of possible 10 for their 56 fatalities

Most Abstracts Published in 2008 Annual report – a 3-way tie – Children's Hospital of Michigan Regional Poison Control Center (Detroit), Hennepin Regional Poison Center (Minneapolis), and Carolinas Poison Center (Charlotte)

Outstanding Case Preparation – Long Island Regional Poison & Drug Information Center. Honorable mention: National Capitol, Oklahoma, Florida Tampa, New Jersey, Carolinas

Most Helpful Regional Poison Center Staff – Georgia Poison Center, Honorable mention: Carolinas, and Long Island.

Appendix B – data definitions

NPDS classifies all calls as either EXPOSURE (concern about an exposure to a substance) or INFORMATION (no exposed human or animal). A call may provide information about one or more exposed person or animal (receptors).

Reason for exposure