Abstract

Background and purpose The properties and performance of a new low-monomer cement were examined in this prospective randomized, controlled RSA study. 5-year data have already been published, showing no statistically significant differences compared to controls. In the present paper we present the 10-year results.

Methods 44 patients were originally randomized to receive total hip replacement with a Lubinus SPII titanium-aluminum-vanadium stem cemented either with the new Cemex Rx bone cement or with control bone cement, Palacos R. Patients were examined using RSA, Harris hip score, and conventional radiographs.

Results At 10 years, 33 hips could be evaluated clinically and 30 hips could be evaluated with RSA (16 Cemex and 14 Palacos). 9 patients had died and 4 patients were too old or infirm to be investigated. Except for 1 hip that was revised for infection after less than 5 years, no further hips were revised before the 10-year follow-up. There were no statistically significant clinical differences between the groups. The Cemex cement had magnitudes of migration similar to or sometimes lower than those of Palacos cement. In both groups, most hips showed extensive radiolucent lines, probably due to the use of titanium alloy stems.

Interpretation At 10 years, the Cemex bone cement tested performed just as well as the control (Palacos bone cement).

One important—and perhaps even the most important—component in modern cemented total hip arthroplasty is the cement-bone interface. Enhanced cementing techniques have improved the outcome in terms of reduced incidence of early loosening and prolonged time until revision in the long term (Britton et al. Citation1996, Mulroy and Harris Citation1996).

One problem in the cementing process is the curing temperature. This is believed to cause bone and cell necrosis, leading to membrane formation and (in the longer term) aseptic loosening—a cause for revision (Mjöberg 1986, Leeson and Lippitt Citation1993). To deal with this problem, Cemex bone cement (Tecres S.p.A., Italy) was developed in the late 1980s. Cemex bone cement was designed to reduce the curing temperature by removal of the smallest sizes of particles in the polymer powder. This would lead to a smaller surface area reacting with monomer. A laboratory test, however, did not show any decrease in curing temperature compared to conventional Palacos (Schering Plough, Labo n.v., Belgium) bone cement (Nivbrant et al. Citation2001).

To examine the clinical properties of this cement and to compare the results with those of Palacos bone cement, a randomized controlled radiostereometric (RSA) trial was initiated. The 5-year results have already been published, and they showed good overall results with little or no differences between the 2 types of cement (Nivbrant et al. Citation2001).

Since it is theoretically possible that different cements may deteriorate differently in the long term, we extended the follow-up and we now report the 10-year results of this study.

Patients and methods

In the original study, 47 hips in 44 patients with osteoarthritis of the hip were randomized to fixation with either Cemex Rx (study) or Palacos R (control) cement (Nivbrant et al. Citation2001). The Cemex Rx cement uses barium sulfate as contrast medium and Palacos uses zirconium oxide. In this study, the Cemex cement was kept at room temperature and mixed in a closed disposable system (Cemex System). The Palacos was kept in a refrigerator before use and mixed in a vacuum system (Optivac; Biomet Cementing Technologies, Sjöbo, Sweden). All operations were performed by 2 experienced surgeons using a posterior approach and third-generation cementing technique.

The components used were a Lubinus SP2 stem made of titanium-aluminum-vanadium alloy and with a CCD angle of 135° (Waldemar Link, Germany), and an all-polyethylene Lubinus cup, gamma-sterilized in air. A 28-mm ceramic femoral head made of aluminum oxide was used in all cases.

For the radiostereometric measurements, tantalum spheres (0.8 mm) were inserted into both the proximal femur and the cement mantle by the surgeon. In order to measure both femoral stem translations and rotations, the femoral stems were equipped with 6 tantalum spheres by the manufacturer. This procedure necessitated the stems being made of titanium-aluminum-vanadium alloy which, at the time when this study was planned, was not seen as negative. By today’s standards, this was obviously a suboptimal decision. However, since the study was designed to compare 2 types of cements, this decision may not necessarily have biased the results and it might instead be regarded as a worst-case scenario.

The RSA examinations were done postoperatively, after 6 months, and at 1, 2, 5, and 10 years with the patient supine. Uniplanar technique was used, with the calibration cage positioned under the patient. The RSA analysis was performed using UmRSA Digital Measure software (RSA Biomedical, Umeå, Sweden).

The migration of the femoral stem was measured both in relation to the femur and in relation to the cement mantle. Rotations of the femoral stem were determined using the 6 stem markers and the center of the femoral head as a segment. Translations of the stem were measured using the gravitational center of the femoral segment. To maintain the precision of the measurements, analysis of stem subsidence in relation to the cement mantle was done only if at least 3 well-defined markers with acceptable configuration and stability could be identified in the cement. Vertical translation (i.e. subsidence) and rotations of the femoral component in relation to the femur and the cement mantle, respectively, are the movements deemed most clinically interesting and they are the ones presented.

The precision of the measurements was evaluated from 30 double examinations where the absolute mean values + 2.7 SD of the differences between 2 subsequent radiostereometric examinations were calculated ().

Table 1. Precision of RSA based on 30 and 16 double examinations. Migration values are given that can be considered to be real with 99% probability in the individual case (absolute mean value of the difference + 2.7 SD)

Harris hip score and pain score were used for clinical evaluation. Radiographic evaluation was performed manually on conventional digitized pelvic radiographs using Mdesk software (RSA Biomedical). We measured the length of the radiolucent lines (RLLs, > 1 mm in width) and related them to the length of the stem. The distribution was registered according to Gruen zones on the 10-year radiographs. The measurements were performed by 2 observers (SMR and PS). SMR had also performed the radiological evaluation of the postoperative radiographs and the 2- and 5-year radiographs. The interobserver reliability was expressed as kappa, according to Altman (1991).

Statistics

Since we were mainly interested in the magnitudes of the translations and rotations, the absolute values of the respective migrations are presented. Because of the relatively small sample size remaining at 10 years and the non-normal distribution of the data, the results are presented graphically as box plots. The difference of the medians for each measured parameter of migration with 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated as described by Campbell and Gardner (Citation1988). For statistical analysis, the Mann Whitney U-test was used, and any p-value of < 0.05 was regarded as being significant.

Results

Mean follow-up time was 119 (113–125) months. Of the 46 hips examined at 5 years, 33 (17 Cemex and 16 Palacos) remained for clinical investigation at 10 years (). 9 patients had died, and 4 patients were too infirm to participate. Except for the patient who was revised due to infection before the 5-year follow-up, there were no revisions up to 10 years. Analysis of stem migration in relation to the femur could be performed in 30 hips (16 Cemex and 14 Palacos). In 3 hips, the RSA radiographs at 10 years were of insufficient quality to permit analysis. At 10 years, 2 patients remained who had been operated bilaterally. In both of these patients, 1 hip was fixed with Cemex and the other with Palacos. Separate analyses with random exclusion of 1 hip of each bilaterally operated patient did not give results that were any different.

Table 2. Patient data at 10-year follow-up

Evaluation of stem subsidence in relation to the cement mantle could only be performed in 10 Cemex hips and in 6 Palacos hips. Reasons for exclusion were (1) problems in visualizing enough markers in the cement mantle on the radiographs, or (2) that their dispersion in the cement mantle was inferior, making the configuration numbers too high to permit analysis.

RSA

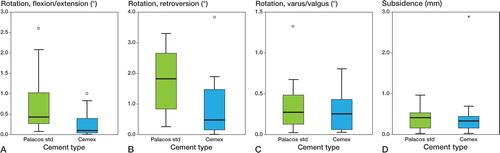

For rotation into flexion/extension and retroversion, the magnitudes were statistically significantly larger in the Palacos group, whereas rotation around the sagittal axis was about equal in both groups. Most implants tilted into varus. The magnitude of subsidence was similar for both groups ( and ).

Figure 1. A. Box plot showing magnitude of rotation of femoral component in relation to the femur around the transverse axis (flexion or extension) at 10-year follow-up. The boxes represent the interquartile distance and the median. The circles represent outliers. B. Box plot showing magnitude of retroversion of femoral component in relation to the femur. C. Box plot showing magnitude of varus or valgus rotation of the femoral component in relation to the femur. D. Box plot showing subsidence of the femoral component in relation to the femur. The asterisk shows an extreme value.

Table 3. Median differences (Cemex - Palacos) and 95% CI of stem migration in relation to bone

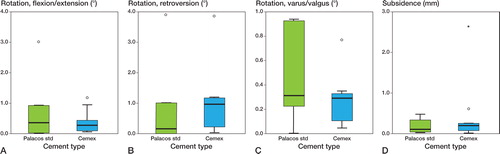

There were no statistically significant differences regarding migration of the femoral component in relation to the cement mantle ( and ). Most of the migration in both groups occurred between the stem and the cement mantle, with little motion occurring between the cement mantle and the bone ( and ).

Figure 2. A. Rotation of the femoral component in relation to the cement mantle around the transverse axis. B. Retroversion of the femoral component in relation to the cement mantle. C. Tilting in to varus or valgus of the femoral component in relation to the cement mantle. D. Subsidence of the femoral component in relation to the cement mantle.

Table 4. Median differences (Cemex - Palacos) and 95% CI of the stem migration in relation to the cement mantle

Radiographic analysis

Radiolucent lines (RLLs) along the stem were found in 22 cases. Most RLLs were located in Gruen zones 2 and 6. The proportion of RLLs in the total interface was 40% (SD 6.3) for Palacos and 50% (SD 4.5) for Cemex. Interobserver reliability was fair to moderate (0.4).

Clinical outcome

Harris hip scores and pain score showed no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups (data not shown).

Discussion

The current standards for preclinical testing of new bone cements (ISO 5833:2002 and ASTM F451-76) are in vitro tests designed to predict in vivo behavior of the bone cement. It is not controversial to assume that a cement will have different properties when examined under other conditions than those applied in the preclinical testing environment. It has, for example, been described that bone cement shows reduced strength and elastic modulus with the passage of time when tested under wet conditions, in contrast to the situation with standard preclinical testing, which is performed in a dry environment and where there is an increase in these properties (Nottrott et al. Citation2008).

Small-scale clinical studies are of value before large-scale introduction to help avoid unnecessary revisions due to material failure—as with the Boneloc disaster, where preclinical tests did not predict clinical failure (Nimb et al. Citation1993, Stürup et al. Citation1994, Kindt-Larsen et al. Citation1995). RSA studies are ideal for small-scale clinical investigations due to the high precision, and they produce reliable data for assessment of orthopedic implants.

In the present study, Cemex bone cement did not show inferior fixation capabilities compared to Palacos up to 10 years postoperatively. Migration was similar, and in some parameters (anterior-posterior rotation and retroversion) it was even lower than for Palacos (). Also, as can be seen in the box plots, the dispersion around the median was usually smaller for Cemex. Palacos bone cement has a very good track record, even with long follow-up, and we do cannot infer that Cemex is a better bone cement based on these measured differences, since they were too small to be clinically significant. Clinically also, there were no differences between the 2 groups. Similar resuts were found in the 5-year follow-up (Nivbrant et al. Citation2001).

As seen in other RSA studies, in both groups most of the migration of the stem occurred between the stem and the cement mantle, with little movement between the cement and bone.

According to the manufacturer of Cemex bone cement, this cement was designed to have a lower curing temperature than conventional cement, therefore improving the fixation. In the laboratory test of Nivbrant et al. (Citation2001), the curing temperature was no different from that of Palacos and this may explain the findings of fairly similar migratory patterns of the two cements in the present study.

The amount and extent of radiolucent lines was high in both groups. We consider this to be related to the fact that a titanium stem was used, since this has been shown to induce high degrees of osteolysis in cemented hip arthroplasty (Scholl et al. Citation2000, Thomas et al. Citation2004). Since most of the migration occurred between the stem and the cement mantle, this movement may have rubbed off titanium particles in large amounts, inducing or enhancing osteolysis. Indeed, Nivbrant et al. (Citation2001) found elevated levels of titanium and aluminum in the serum of these patients at 5 years, thus corroborating this statement.

In conclusion, Cemex performed as well as Palacos, and in some respects even better than Palacos. However, we regard these differences in the cements to be too small to be of any clinical importance. Based on these results, we conclude that Cemex bone cement can be safely used in total hip arthroplasty.

PS: RSA analysis, statistics, data interpretation, initial manuscript draft. JD, SR: Radiographic analysis, statistics, parts of manuscript writing. BN: Initial study design, one of the operative surgeons, contributed to parts of the manuscript. KGN: Statistics, data interpretation, contributed to parts of the manuscript and edited parts of the manuscript

Financial support was obtained from the IngaBritt and Arne Lundberg Research Foundation, the Doctor Félix Neubergh Foundation, the Swedish Medical Research Foundation, Tecres S.p.A. (Italy), Schering Plough (Sweden), and Waldemar Link (Germany).

No competing interests declared.

- Altman Douglas G. Practical statistics for medical research. Chapman and Hall/CRC 1991: 404-10.

- Britton AR, Murray DW, Bulstrode CJ, McPherson K, Denham RA. Long-term comparison of Charnley and Stanmore design total hip replacements. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1996; 78: 802-8.

- Campbell MJ, Gardner MJ. Calculating confidence intervals for some non-parametric analyses. Br Med J 1988; 296: 1454-6.

- Kindt-Larsen T, Smith DB, Steen Jensen J. Innovations in acrylic bone cement and application equipment. J Appl Biomat 1995; 6: 75-83.

- Leeson MC, Lippitt SB. Thermal aspects of the use of polymethylmethacrylate in large metaphyseal defects in bone. A clinical review and laboratory study. Clin Orthop 1993; (295): 239-45.

- Mjöberg B. Loosening of the cemented hip prosthesis. The importance of heat injury. Acta Orthop Scand (Suppl 221) 1986; 1-40.

- Mulroy WF, Harris WH. Revision total hip arthroplasty with use of so-called second-generation cementing techniques for aseptic loosening of the femoral component. A fifteen-year-average follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1996; 78: 325-30.

- Nimb L, Stürup J, Steen Jensen J. Improved cortical histology after cementation with a new MMA-DMA-IBMA bone cement: An animal study. J Biomed Mater Res 1993; 27: 565-74.

- Nivbrant B, Kärrholm J, Röhrl S, Hassander H, Wesslen B. Bone cement with reduced proportion of monomer in total hip arthroplasty: preclinical evaluation and randomized study of 47 cases with 5 years’ follow-up. Acta Orthop Scand 2001; 72: 572-84.

- Nottrott M, Molster AO, Moldestad IO, Walsh WR, Gjerdet NR. Performance of bone cements: are current preclinical specifications adequate? Acta Orthop Scand 2008; 79: 826-31.

- Scholl E, Eggli S, Ganz R. Osteolysis in cemented titanium alloy hip prosthesis. J Arthroplasty 2000; 15: 570-5.

- Stürup J, Nimb L, Kramhøft Steen Jensen J. Effects of polymerization heat and monomers from acrylic cement on canine bone. Acta Orthop Scand 1994; 65: 20-3.

- Thomas SR, Shukla D, Latham PD. Corrosion of cemented titanium femoral stems. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2004; 86: 974-8.