Abstract

Background and purpose Analgesics can have undesirable effects.

We assessed whether a single preoperative dose of 120 mg etoricoxib reduces the need for additional opioids after therapeutic arthroscopic knee surgery.

Methods A double-blind, placebo-controlled study was performed at a single center. 66 patients scheduled to undergo elective therapeutic knee arthroscopy were included. They were randomly selected to be given either 120 mg of etoricoxib (n = 33) or placebo (n = 33) 1 hour before induction of general anesthesia. A patient-controlled analgesia device was used postoperatively. We recorded total postoperative morphine consumption over 24 h, degree of pain as assessed with a visual analog scale, degree of satisfaction, and occurrence of adverse effects.

Results Mean total morphine consumption during the first 24 h was 24 (9–60) mg in the placebo group and 9 (0–34) mg in the etoricoxib group. In the etoricoxib group, pain intensity levels at rest were reduced and patient satisfaction with the analgesia provided was higher during the first postoperative day. There was no difference in the incidence of typical adverse effects of opioids in the 2 groups.

Interpretation Etoricoxib is a suitable premedication to use before therapeutic arthroscopic knee surgery, as it reduced patients’ morphine requirements.

There have been various studies on the preoperative or intraoperative use of coxibs for the reduction of postoperative morphine consumption. Parecoxib has been shown to have an opioid-sparing effect after coronary bypass surgery and discectomy, but not after craniotomy (Khalil et al. Citation2006, Riest et al. Citation2008, Jones et al. Citation2009). Of the currently registered COX-2 inhibitors, etoricoxib has the longest duration of analgesic action, lasting 22–24 hours. Its rapid absorption after oral intake results in peak plasma concentrations after 1 h (Agrawal et al. Citation2001, Dallob et al. Citation2003). Various studies have shown that etoricoxib has both efficacy and an opioid-sparing effect when used in the treatment of acute postoperative pain (Clarke et al. Citation2009). Several studies have examined its use preoperatively and have confirmed its efficacy in providing pain relief after various kinds of gynecological procedures (Liu et al. Citation2005, Chau-in et al. Citation2008, Lenz and Raeder Citation2008) and after abdominal (Puura et al. Citation2006), thyroid (Smirnov et al. Citation2008), and trauma surgery (Siddiqui et al. Citation2008).

There are no data on the efficacy of the preoperative administration of a single dose of etoricoxib for the attenuation of postoperative pain after therapeutic knee arthroscopy that is performed under general anesthesia. We therefore wanted to determine whether a single preoperative dose of 120 mg etoricoxib before knee arthroscopy would reduce patients’ postoperative opioid consumption.

Patients and methods

The study was performed according to ICH-GCP (International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use – Good Clinical Practice) guidelines. We also observed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, had the study authorized by the relevant national authority, and had it approved by the appropriate Research and Ethics Committee prior to enrollment. The study was performed under EudraCT No. 2006-000451-17 between June 2006 and June 2009 at the Marienkrankenhaus, Soest, Germany. The trial was also registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov under NCT00738608, protocol number 2006-000451-17.

Participants

We recruited male and female patients between 19 and 70 years of age who were scheduled to undergo therapeutic arthroscopy (e.g., meniscal surgery, joint shaving) of the knee under general anesthesia. Only patients undergoing therapeutic arthroscopy (as opposed to diagnostic arthroscopy) were selected, because patients undergoing diagnostic procedures may not suffer enough postoperative pain to justify treatment with etoricoxib. All patients who undergo therapeutic knee arthroscopy are routinely treated as inpatients for 2 days after surgery. Before they were enrolled in the study, the patients had to provide written informed consent.

Patients with a creatinine clearance of ≤ 50 mL/min (calculated using the Cockcroft-Gault formula); opiate addiction; a known hypersensitivity to the active ingredient in etoricoxib or to any of the excipients in the film-coated placebo tablet, to NSAIDs, or to aspirin; patients with active peptic ulcer or active gastrointestinal bleeding, inflammatory bowel disease, liver cirrhosis, cholestasis, elevated liver function tests (i.e. ALT or AST levels more than 3 times the upper limit of normal); or severe hepatic dysfunction (i.e. patients with a serum albumin concentration of < 25 g/L or with a Child-Pugh score of ≥ 10) were excluded for safety reasons. Other exclusion criteria were pregnancy; breast feeding; congestive heart failure (i.e. patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II–IV heart failure); hypertension with inadequately controlled blood pressure (BP) (i.e. systolic BP > 160 mmHg or diastolic BP > 100 mmHg); a known history of ischemic heart disease; peripheral arterial disease; and/or cerebrovascular disease.

Interventions, randomization, blinding, and concealment of allocation

Patients received either a single oral tablet of etoricoxib (120 mg) or one look-alike film-coated placebo tablet 1 h before induction of anesthesia for arthroscopy. A randomization code was prepared at the hospital using the Microsoft Excel 2007 function RANDBETWEEN (1;2) by a person not involved in data collection. Generation of the list was repeated until a list with equal distribution of 1 and 2 resulted. Etoricoxib and placebo were prepared according to this randomization list and labeled with consecutive numbers from 1 to 66, and patients received the medication with the lowest available number. The patients, nurses, surgeons, and anesthesiologists directly involved in patient care were blind regarding the content of the oral study medication for the duration of the study (i.e. until all queries were resolved and the database was closed). For every patient, a sealed envelope with the treatment allocation was kept at the intensive care unit of the hospital so that immediate decoding of the study medication would have been possible for individual patients in the event of a serious adverse reaction.

Study schedule, outcomes, and objectives

Before surgery, patients underwent standard preoperative examinations, including electrocardiography; physical examination; determination of vital signs; urine pregnancy test (in women of childbearing age); and measurement of hematological, blood coagulation, and standard clinical chemistry parameters. In all cases, arthroscopy was performed under general anesthesia (i.e. total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) with propofol and fentanyl).

After the end of surgery and anesthesia, the patient was transferred to the recovery room, where he was immediately connected to a PCA pump. There, 30 min after the end of anesthesia (t = 0), all patients were able to answer questions and to rate their pain on a 10-cm visual analog scale (VAS) at rest and during movement (range of the scales: 0–10, with 0 = no pain and 10 = worst imaginable pain). After checking of stable vital signs and full recovery, the patient was transferred from the recovery room to an orthopedic ward. At the ward, 2 h, 4 h, 6 h, and 24 h after the first measurement, the patients were visited by a physician (HL) and the measurements were repeated. Analgesia was administered according to usual hospital standards using a PCA pump (which was set to deliver a single bolus of morphine at a dose of 0.02 mg/kg body weight up to 6 times per hour). The amount of morphine that had been used by the time points specified above and the time of the administration of the first PCA pump dose were documented. The primary endpoint of the study was to determine the extent to which a single preoperative dose of 120 mg etoricoxib reduced postoperative opioid consumption during the 24-hour period after therapeutic knee arthroscopy.

Patient alertness was scored on a numerical rating scale (0 = alert and oriented, 1 = slightly drowsy, 2 = mildly sedated but arousable by shaking, and 3 = deeply sedated, not arousable) by the anesthesiologist responsible for the recovery room. Heart rate (defined normal range: 40–120/min.), blood pressure (defined normal range: systolic 95–195 mmHg) and respiratory rate (defined normal range: 10–25/min.) were measured at the times specified above. The patients were also asked if they were satisfied with the level of analgesia that had been achieved at those times: (1 = very satisfied, 2 = satisfied, 3 = dissatisfied, and 4 = very dissatisfied; 1 and 2 were regarded as successful pain management and 3 and 4 were regarded as unsuccessful pain management).

Sample size and statistical analysis

Because there were insufficient data available in the literature on the preoperative use of etoricoxib at the time this study was planned, the sample size estimate was based on several assumptions. We assumed that patients in the placebo group would require a mean morphine dose of 55 mg during the first 24 h after surgery and those patients who received etoricoxib would require a mean morphine dose of 36 mg (35% less) over the same time period. We assumed a common standard deviation of 22 mg (i.e. 40% of the mean morphine dose in the placebo group). We also assumed an alpha of 0.05, a beta of 0.10, and a dropout rate of 10%. These assumptions resulted in a sample size of 33 patients per group.

The data are presented either as mean (SD) or as median (range). They were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Where there was normal distribution, Student’s t-test was used to compare the two groups at each time point. Otherwise, non-parametric tests such as the Mann-Whitney test were used. Patients’ overall morphine requirements, VAS scores, and vital signs over the first 24-h period postoperatively were examined by repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences in the rates of side effects between the groups were calculated using the chi-2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Analyses were performed using SPSS software version 16. All tests were two-tailed, and differences were considered statistically significant for p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the patients included

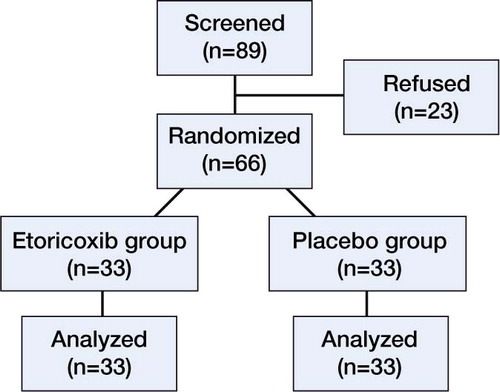

Between June 1, 2006 and June 30, 2009, the study center screened 89 patients for inclusion and recruited 66 patients, 33 of whom were allocated to the etoricoxib group and 33 of whom were allocated to the placebo group. 23 patients refused to participate in the study. All participating patients completed the study, which ended as scheduled 24 h after recruitment of the last patient. No patients were excluded for protocol violations and no sets of data were incomplete. Thus, only 1 analysis set was evaluated (). Baseline data are given in .

Figure 1. Flow of participants through the trial. 23 of 89 patients were not randomized for the following reasons: 16 declined to participate, 4 did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 3 were rejected for other reasons (they chose regional anesthesia).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients included

Morphine consumption

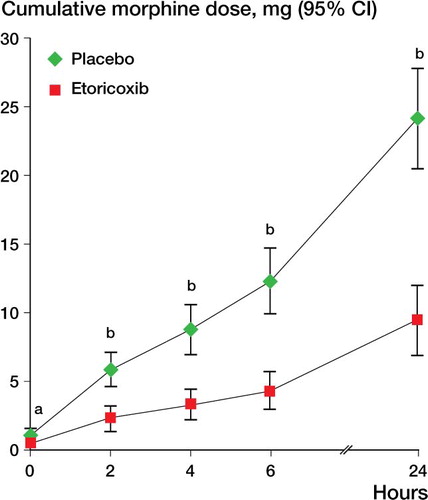

The total morphine consumption over the 24-h observation period was 9.4 (SD 7.3) mg in the etoricoxib group and 24.1 (SD 10.6) mg in the placebo group. Thus, the patients who received etoricoxib required 14.7 mg (95% CI: 10.2–19.2) less morphine during that period than the patients who received the placebo, giving a relative reduction of 61% (p < 0.001, ANOVA). shows the cumulative morphine dose required by the patients in both treatment groups at the 5 time points measured.

Figure 2. Cumulative morphine consumption over the first 24 hours postoperatively. a p < 0.015; b p < 0.001.

The placebo patients required their first morphine dose via PCA pump in the recovery room at 0 (0–12) h, as compared to 2 (0–∞) h in the etoricoxib patients (p < 0.01, Fisher’s exact test). Despite their earlier and higher morphine requirements, the placebo patients reached the target pain score of 3 after 4 (0–∞) h, much later than the patients who received etoricoxib, who reached that target after 0 (0–∞) h (p = 0.003, Fisher’s exact test).

Analgesia

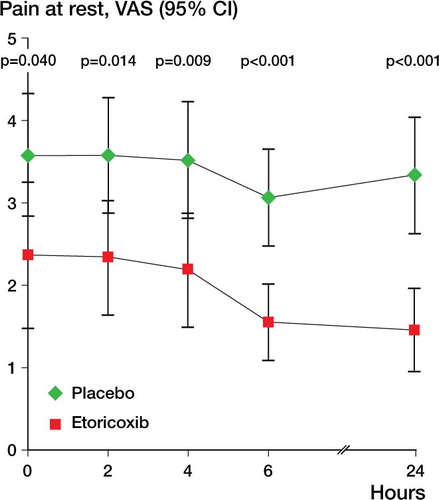

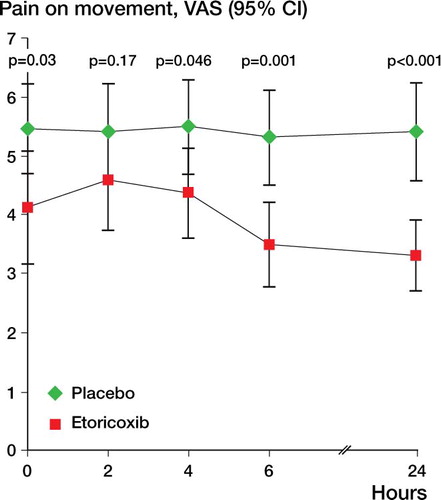

Overall pain at rest was lower in the etoricoxib group than in the placebo group (p = 0.01, ANOVA). For overall pain on movement, there was no statistically significant difference between groups (p = 0.07). Subsequent tests for all single time points showed that patients who received etoricoxib had significantly less pain at rest and on movement at 0, 4, 6, and 24 h ( and ).

Patient satisfaction

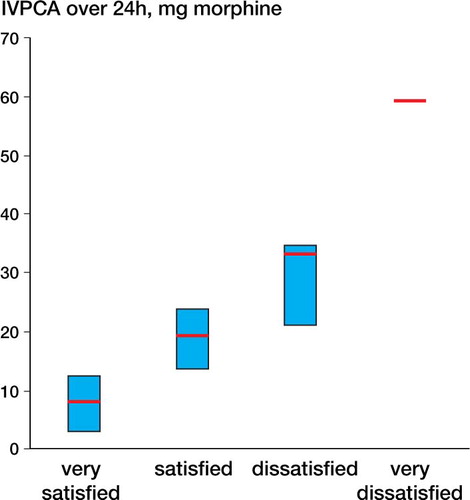

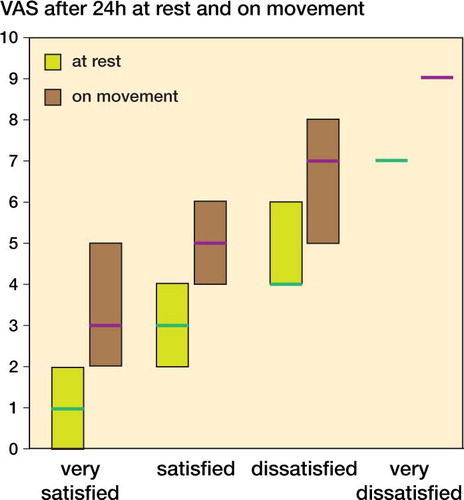

Patient satisfaction at each time point was significantly higher in the etoricoxib group than in the placebo group (). At the end of the 24-h period, the proportion of patients with successful pain management was 56/66 overall, 32/33 in the etoricoxib group and 24/33 in the placebo group. shows the intravenous PCA use and shows the VAS scores at rest and on movement for all patients, grouped by the subjective rating of the patients (median and interquartile range (25%–75%)).

Table 2. Patient satisfaction (1–4) after etoricoxib (E) and placebo (P)

Vital signs and adverse events

Degree of sedation (chi-squared test), heart rate, and blood pressure (t-test) were similar in both groups at each time point. For the first 4 h, measured respiratory rates differed between the groups (p = 0.003, t-test), but the difference was of no clinical importance. For all measurements, respiratory rate was above 10/min in all patients.

8 patients suffered 12 adverse events: 6 patients (10 events) in the placebo group and 2 patients (2 events) in the etoricoxib group. 1 patient in the etoricoxib group suffered from nausea and the other experienced shivering. In the placebo group, 5 patients suffered from nausea, 3 from dizziness, 1 from vomiting, and another from hypotension. Between groups, the difference in the number of patients suffering adverse events was not statistically significant (p = 0.3, Fisher’s exact test).

Discussion

We found that 120 mg of etoricoxib given as a single oral dose 1 h before therapeutic arthroscopy reduced morphine consumption during the 24 h that followed, by approximately 60%. The patients who received etoricoxib consumed less morphine and they reported less pain. The analgesic superiority of etoricoxib (compared to placebo with increased morphine doses) ranged from 8 mm to 21 mm on a 100-mm VAS. The advantage may be small but clinically relevant. Several authors have found that differences as small as 6–10 mm on the VAS are perceptible for patients in pain (Kelly Citation1998, Eberle and Ottillinger Citation1999, Ehrich et al. Citation2000). Etoricoxib provided superior analgesia, even though all the patients could dose their morphine according to their individual requirements for achievement of freedom from pain. Thus, even though the placebo patients used more than twice the amount of morphine than the etoricoxib patients, they had inferior analgesia and were less satisfied with their analgesic therapy. Etoricoxib may control other aspects of orthopedic pain that are not responsive to opioids, such as pain caused by swelling and inflammation.

It has been shown using large patient datasets that postoperative consumption of analgesics is an uncertain method of measuring the analgesic efficacy of a pain therapy designed to limit pain during and after surgery (Mhuircheartaigh et al. Citation2009, Moore et al. Citation2011). Also, in our patient population most patients required relatively modest analgesia, whereas a small proportion required large amounts (). As with the findings of Moore et al. 2009, more severe pain () and greater morphine use were associated with less satisfaction with the level of analgesia. It is therefore important to analyze the degree of patient satisfaction and pain, not just the consumption of analgesics. Our results support the idea that prophylactic analgesia leads to more patient satisfaction than intravenous PCA alone (Mhuircheartaigh et al. Citation2009).

Several studies have examined the opioid-sparing effect of etoricoxib (120 mg) in orthopedic surgery patients. In those studies, patients’ opioid requirements were reduced to a similar extent, although the drug was only administered preoperatively in one study. In a study that included patients who underwent fixation of upper or lower limb fractures, administration of etoricoxib (120 mg) preoperatively reduced their postoperative morphine consumption by 21% (Siddiqui et al. Citation2008). Rasmussen et al. (Citation2005) found that etoricoxib (120 mg) given after elective total hip or knee replacement reduced patients’ consumption of a hydrocodone/paracetamol combination (7.5/500 mg) by 35% relative to placebo.

The results we obtained regarding the opioid-sparing effects of etoricoxib are in the upper range of those observed in other studies. This was probably due to the homogeneous patient population and the highly standardized approach to arthroscopy and patient care at our institution, which is a characteristic disadvantage of all single-center studies. Another limitation of our study was the relatively low analgesic demand of the patients during the observation period, which was less than 50% of the expected dosage. Although several effects of the preoperative medication have been shown, the number of patients included was small and the generalizability to other settings is limited.

It will be interesting to find out whether patients in other settings derive as much or even more benefit from the preoperative administration of etoricoxib. One possible advantage of premedication with etoricoxib may be a reduced incidence of opioid-induced side effects. Our study was probably too small to show this effect; thus, studies with larger sample sizes are needed. In combination with reducing the level of pain in patients, the alleviation of opioid-induced side effects would significantly improve patient comfort in the postoperative setting. If this effect can be proven, etoricoxib could be recommended as a routine perioperative medication.

PL designed the study and was the principal investigator. HL collected the data and performed the anesthesia in each patient. PF was responsible for the statistics. PL and PF contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

This work was sponsored by a grant from Merck and Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ. The sponsor provided financial support (a fee for the ethical commission and patient insurance), drugs, and placebo used in the study. PL has also received lecture fees from Merck and Co. None of the other authors have any competing interests to declare.

- Agrawal NG, Porras AG, Matthews CZ, Woolf EJ, Miller JL, Mukhopadhyay S, . Dose proportionality of oral etoricoxib, a highly selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol 2001; 41 (10): 1106-10.

- Chau-in W, Thienthong S, Pulnitiporn A, Tantanatewin W, Prasertcharoensuk W, Sriraj W. Prevention of post operative pain after abdominal hysterectomy by single dose etoricoxib. J Med Assoc Thai 2008; 91 (1): 68-73.

- Clarke R, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose oral etoricoxib for acute postoperative pain in adults (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev.; 2009; 5 (2).

- Dallob A, Hawkey CJ, Greenberg H, Wight N, De Schepper P, Waldman S, . Characterization of etoricoxib, a novel, selective COX-2 inhibitor. J Clin Pharmacol 2003; 43 (6): 573-85.

- Eberle E, Ottillinger B. Clinically relevant change and clinically relevant difference in knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1999; 7 (5): 502-3.

- Ehrich EW, Davies GM, Watson DJ, Bolognese JA, Seidenberg BC, Bellamy N. Minimal perceptible clinical improvement with the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index questionnaire and global assessments in patients with osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 2000; 27 (11): 2635-41.

- Jones SJ, Cormack J, Murphy MA, Scott DA. Parecoxib for analgesia after craniotomy. Br J Anaesth 2009; 102 (1): 76-9.

- Kelly AM. Does the clinically significant difference in visual analog scale pain scores vary with gender, age, or cause of pain? Acad Emerg Med 1998; 5 (11): 1086-90.

- Khalil MW, Chaterjee A, Macbryde G, Sarkar PK, Marks RR. Single dose parecoxib significantly improves ventilatory function in early extubation coronary artery bypass surgery: a prospective randomized double blind placebo controlled trial. Br J Anaesth 2006; 96 (2): 171-8.

- Lenz H, Raeder J. Comparison of etoricoxib vs. ketorolac in postoperative pain relief. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2008; 52 (9): 1278-84.

- Liu W, Loo CC, Chiu JW, Tan HM, Ren HZ, Lim Y. Analgesic efficacy of pre-operative etoricoxib for termination of pregnancy in an ambulatory centre. Singapore Med J 2005; 46 (8): 397-400.

- Mhuircheartaigh RJ, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Analysis of individual patient data from clinical trials: epidural morphine for postoperative pain. Br J Anaesth 2009; 103 (6): 874-81.

- Moore RA, Mhuircheartaigh RJ, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Mean analgesic consumption is inappropriate for testing analgesic efficacy in post-operative pain: analysis and alternative suggestion. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2011; 28 (6): 427-32.

- Puura A, Puolakka P, Rorarius M, Salmelin R, Lindgren L. Etoricoxib pre-medication for post-operative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2006; 50 (6): 688-93.

- Rasmussen GL, Malmstrom K, Bourne MH, Jove M, Rhondeau SM, Kotey P, . Etoricoxib provides analgesic efficacy to patients after knee or hip replacement surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Anesth Analg 2005; 101 (4): 1104-11.

- Riest G, Peters J, Weiss M, Dreyer S, Klassen PD, Stegen B, . Preventive effects of perioperative parecoxib on post-discectomy pain. Br J Anaesth 2008; 100 (2): 256-62.

- Siddiqui AK, Sadat-Ali M, Al-Ghamdi AA, Mowafi HA, Ismail SA, Al-Dakheel DA. The effect of etoricoxib premedication on postoperative analgesia requirement in orthopedic and trauma patients. Saudi Med J 2008; 29 (7): 966-70.

- Smirnov G, Terava M, Tuomilehto H, Hujala K, Seppanen M, Kokki H. Etoricoxib for pain management during thyroid surgery–a prospective, placebo-controlled study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008; 138 (1): 92-7.