Abstract

Background and purpose Guidelines for fracture treatment and evaluation require a valid classification. Classifications especially designed for children are available, but they might lead to reduced accuracy, considering the relative infrequency of childhood fractures in a general orthopedic department. We tested the reliability and accuracy of the Müller classification when used for long bone fractures in children.

Methods We included all long bone fractures in children aged < 16 years who were treated in 2008 at the surgical ward of Stavanger University Hospital. 20 surgeons recorded 232 fractures. Datasets were generated for intra- and inter-rater analysis, as well as a reference dataset for accuracy calculations. We present proportion of agreement (PA) and kappa (K) statistics.

Results For intra-rater analysis, overall agreement (κ) was 0.75 (95% CI: 0.68–0.81) and PA was 79%. For inter-rater assessment, K was 0.71 (95% CI: 0.61–0.80) and PA was 77%. Accuracy was estimated: κ = 0.72 (95% CI: 0.64–0.79) and PA = 76%.

Interpretation The Müller classification (slightly adjusted for pediatric fractures) showed substantial to excellent accuracy among general orthopedic surgeons when applied to long bone fractures in children. However, separate knowledge about the child-specific fracture pattern, the maturity of the bone, and the degree of displacement must be considered when the treatment and the prognosis of the fractures are evaluated.

Long bone fractures are the main reason for emergency admission of children to orthopedic departments (Deakin et al. Citation2007). Fracture classification is essential for comparison of epidemiological details and for quality assurance of different fracture treatment algorithms. Until recently, multiple classification systems based on anatomical segments or morphological patterns of fracture were used simultaneously to describe long bone fractures. The Salter-Harris classification of lesions involving the physeal plate and the Gartland classification of distal humeral fractures are well-known examples (Gartland Citation1959, Salter Citation1963). Some childhood fracture types and segments have several available classification systems while others have none.

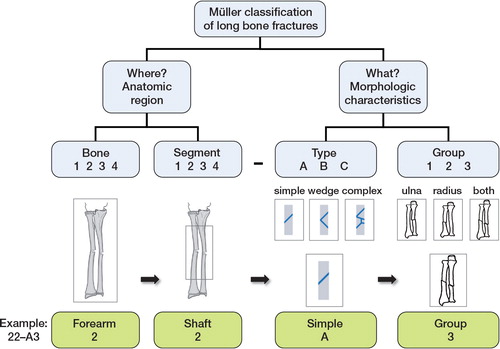

The Müller comprehensive classification of long bone fractures (Müller et al. Citation1990) () was developed as an overall fracture classification system, and has been adapted for adult long bone fractures by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (AO) and by the Orthopedic Trauma Association (OTA) (Marsh et al. Citation2007). However, it has not been used widely in the classification of pediatric fractures. This system does not cover some important aspects of fractures in children. The pediatric skeleton is softer, is more elastic, and includes the non-calcified growth plates and the partially calcified epiphysis. Consequently, depending on the maturity of the bone and the trauma mechanism involved, the bone gives way differently. Very often, at least part of the bone is deformed rather than broken apart, resulting in fractures with specific patterns in children—including bowing, buckles, and green-stick fractures. Moreover, the growth plate is less rigid than the surrounding bone, creating a stress riser, and it is therefore injured relatively frequently.

AO introduced a child-specific classification system—the AO pediatric comprehensive classification of long bone fractures (PCCF)—in 2006 (Slongo et al. Citation2006). Licht und Lachen für kranke Kinder (Li-La) recently introduced an alternative classification system, the Li-La classification (Schneidmuller et al. Citation2011). Both systems are based on previous attempts to modify the Müller classification of children’s fractures (Slongo et al. Citation1995, von Laer et al. Citation2000). They also incorporate well-established classification systems such as the Salter-Harris and Gartland classifications. In the last 2 decades, there has been major concern about the reliability of most known classification systems. Consequently, the PCCF has been studied according to a 3-phase validation concept, as introduced by Audigè et al. (2005). The results have been promising, at least among experts (Slongo et al. Citation2007a,Citationb). In the third phase, which has not yet been performed, the classification should be tested in prospective clinical studies to assess its implications for treatment options and outcome.

Starting in January 2004, all inpatient procedures performed for both adult and pediatric fractures of long bones were classified according to a slightly adjusted Müller classification () and reported to the Fracture and Dislocation Registry of Stavanger University Hospital (Meling et al. Citation2009, Citation2010). Other comprehensive classification systems were scarcely established for pediatric fractures at that time. We have analyzed the reliability and accuracy of the Müller classification as applied to childhood fractures.

Patients and methods

Stavanger University Hospital (SUH) serves as the only primary emergency care facility in the region. The catchment area consists of a mixed urban and rural population of approximately 317,000 inhabitants, of which 73,000 (23%) are below 16 years of age. Adult fractures have been considered seperately elsewhere (Meling et al. Citation2012).

All orthopedic surgeons working for the hospital perform pediatric operations/reductions irrespective of their other orthopedic subspecialty. 242 pediatric long bone fractures were reported during the study year (2008). 1 pathological fracture (bone cyst) was excluded. 3 patients with synchronous ipsilateral fractures were excluded. 6 fractures were excluded because radiographs were not accessible for re-evaluation. Thus, 232 long bone fractures were considered for re-evaluation and were included in the study.

20 of the 23 surgeons who contributed to the original dataset were still working in the department and were available to participate in the re-scoring. Thus, 184 (79%) of the 232 fractures were included in the intra-rater analysis ( and ).

Table 1. Overall agreement, reliability, and accuracy for all signs of the Müller comprehensive classification of long bone fractures in childhood fractures

Table 2. Agreement, reliability, and accuracy according to each sign in the Müller classification of long bone childhood fractures. Only the codes that were given the same classification code at the previous signs were considered when the next sign was calculated

Intra- and inter-rater reliability and accuracy calculations are presented as both percentage of agreement and kappa statistics. Intra-rater refers to a situation where the same observer, on separate occasions, classifies a fracture. Inter-rater refers to a situation in which the same cases are rated by different observers. Agreement indicates how similar the fracture classification datasets are, and it is measured as the percentage of even ratings (the proportion of agreement; PA) between each dataset. Reliability refers to how similar the datasets are relative to the similarity expected to occur by chance alone. Reliability was measured by kappa statistics (K). Accuracy refers to the correctness of the dataset when compared to a reference dataset.

The original fracture codes were reported by the surgeon in charge of each operation in the study period. Operation notes and perioperative radiographs of the same fractures (but not the original code) were presented to the same surgeons in a corresponding manner in November 2009. The resulting dataset was compared to the original code during the calculation of intra-rater agreement and reliability. The fractures treated by surgeons who no longer worked at the institution (in November 2009) were excluded from parts of the analysis. A randomized selection (50% of the fractures that were operated by surgeons in 2008) was presented in the same way to an average experienced orthopedic resident (with 3 years of orthopedic training). The resulting dataset was compared to the original dataset to calculate the inter-observer agreement and reliability.

All the original codes were checked (unblinded) and re-coded, as deemed necessary by an experienced trauma orthopedic surgeon. Only the fractures that the first expert re-coded were presented to another experienced orthopedic trauma surgeon. Where the experts’ preliminary coding did not agree, they reviewed the fractures together, making a final consensus code. The resulting reference code dataset was compared to the other datasets when accuracy calculations were performed.

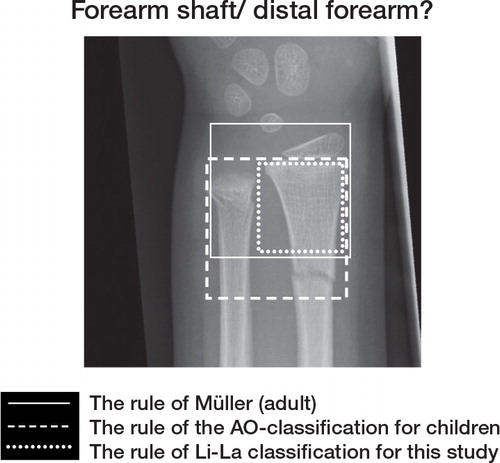

We used the first 4 signs of the Müller classification of long bone fractures (Müller et al. Citation1990) (). Only 2 modifications to the classification were required. First, the definition of fracture was slightly altered, such that bending and incomplete disruptions of the cortices were considered as fractures. Secondly, because ossification of the epiphysis is age-dependent, the extent of the bone is difficult to evaluate from plain radiographs (). Consequently, the growth plate was considered as the distal/ proximal marking when the “rule of square” was used. Like the Li-La classification, and in contrast to the PCCF, we did not include pairs of bones, i.e. radius/ulna and tibia/fibula, in the square (Slongo et al. Citation2006, Schneidmuller et al. Citation2011).

Figure 2. The rule of the square: “The proximal and distal segments of long bones are defined by a square whose sides are the same length as the widest part of the epiphysis” (Müller et al. Citation1990). Müller classification: The width defined by both bones. The reference line defined as the most distal (or proximal) part of the bone. Li-La classification (and in this study): The width defined by one bone (radius). The reference line defined as the epiphyseal plate.

AO pediatric classification: The width defined by both bones. The reference line defined as the epiphyseal plate. The proximal lines of the squares define the border between the diaphysis and the metaphysis. The fracture illustrated is defined as a forearm shaft fracture according to the Müller and Li-La classifications (and in this study), and as a distal forearm fracture according to the AO pediatric classification.

Reliability was measured according to kappa statistics. Kappa values range from –1 (no agreement) to 1 (complete agreement). A value of 0 indicates no better agreement than expected by chance alone. The guidelines of Landis and Koch were used when the results were analyzed (K = 0.81–1.00: excellent; K = 0.61–0.80 substantial; K = 0.41–0.60 moderate; and K = 0.21–0.40: fair) (Landis and Koch Citation1977).

Statistics

The software packages SPSS version 15 and R version 12.2.2 (http://www.r-project.org) were used for statistical analyses. Selection of fractures for inter-rater analysis was performed in SPSS by randomization.

Intra- and inter-rater reliability are presented using Cohen’s kappa (kappa agreement), which was calculated in R.12.2.2 using the package psy and irr (Falissard Citation2009). 95% CIs were estimated according to an adjusted bootstrap percentile CI by using a bootstrap CI of Light’s kappa (Efron and Tibshirani Citation1993, Gwet Citation2010).

Ethics

The Norwegian Social Science Data Service approved the registry. The Regional Ethics Committee gave its consent for the study on 21 June 2007 (number 152.07).

Results

146 of the 184 fractures were given the same classification code according to fracture group (4 signs of the classification), giving a PA of 79% and a kappa agreement of 0.75 (CI: 0.68–0.81).

In the inter-rater analysis, 108 pairs of fracture classification codes were analyzed. The PA was calculated as 77% (83 of 108) and the kappa agreement as 0.71 (CI: 0.61–0.80) ( and ).

196 (84%) of the 232 codes in the original classification were accepted as correct by the first expert. The remaining 36 fractures (16%) were presented to another expert. Of these, 15 fractures were given the same codes by both experts. The remaining 21 fracture codes (9% of the total) were agreed on by consensus between the experts.

201 (87%) of the 232 original classification codes were correctly recorded according to the reference code dataset, giving a kappa agreement of 0.84 (CI: 0.78–0.88). Furthermore, 140 of 184 of the surgeons’ blinded re-codings (76%) were correctly classified ( and ). The kappa agreement was calculated as 0.72 (CI: 0.64–0.79). Accuracy for the most frequent segments according to 3 and 4 signs in the Müller code is presented in .

Table 3. Accuracy of the surgeons’ blinded re-coding for the most frequent bone segments according to 3 and 4 signs of the classification

Discussion

According to the most frequently used guidelines for interpretation of kappa agreement (Landis and Koch Citation1977), the intra- and inter-rater reliability and accuracy of the Müller classification were excellent when considering three signs of the classification and substantial when four signs were considered. When each sign of the classification was considered individually, most kappa values were excellent ().

There are many pitfalls in performing a reliability study, especially when it comes to the interpretation of kappa values (Audige et al. Citation2004, Sim and Wright Citation2005, Karanicolas et al. Citation2009). The incidence of the different fractures varied considerably (). Consequently, our study does not permit interpretation of details in the subclassification; the resulting CIs were too wide. However, interpretation of the general applicability of the classification should be justified, as illustrated by the narrow CIs ( and ).

Table 4. Distribution of the fractures according to the reference dataset

Determinination of the second sign of the Müller classification proved to be particularly difficult in childhood fractures (). Reviewing details of the surgeons’ second dataset, 12 of the distal forearm fractures were misclassified as forearm shaft fractures. None of the forearm shaft fractures were misclassified as distal forearm fractures. Difficulty in using the Müller “rule of the square” may be one reason for this problem (Müller et al. Citation1990) (). Another reason might be that the surgeons believed that a distal antebrachial fracture (both bones) had to be recorded as a diaphyseal fracture. The first expert (TM), re-classified the 165 forearm fractures in a blind manner (data not shown) using the PCCF’s “rule of the square”. The proportion of distal forearm fractures increased from 95 of 165 (58%) to 111 of 165 (67%).

Consideration of the widths of both bones and not only the radius when using the rule of the square improved the accuracy of classifying the fracture into epiphyseal (E), metaphyseal (M), or diaphyseal (D) from a kappa value of 0.78 to one of 0.98 (Audige Citation2004). The latter finding has not been reproduced among less experienced surgeons, whose results—split into kappa values for E, M, and D—were 0.66, 0.80, and 0.91, respectively (Slongo et al. Citation2007a). The corresponding articular/non-articular classification of the Li-La classification was performed at an overall kappa value of 0.88 (Schneidmuller et al. Citation2011). Validation has also been evaluated according to the child-specific patterns. The settings of the child-specific patterns among PCCF experts were 0.92, 0.91, and 0.84 for E, M, and D, respectively (Audige Citation2004). However, for surgeons with average experience the corresponding kappa values were 0.51, 0.63, and 0.48, respectively (Slongo et al. Citation2006). For the Li-La classification, the overall kappa for the specific child fracture code was 0.72 (Schneidmuller et al. Citation2011). These results are not easily compared to those in our study. However, generally speaking, the kappa values listed in and appear to exceed those in the latter studies (Slongo et al. Citation2006, Schneidmuller et al. Citation2011).

To determine the treatment and the prognosis of a fracture, it is necessary to know how stable the fracture is and the possible spontaneous correction of the displacement. This matter is often not entirely considered in classification systems because it may lead to poor reliability (Kreder et al. Citation1996). The Müller classification, for instance, does not generally consider the level of displacement of the fracture fragments. The level of displacement is only partially considered in the PCCF (for supracondylar fractures of the humerus and proximal fractures of the radius), and the level of displacement and the maturity of the bone are generally considered in the Li-La (non-displaced/tolerably displaced and non-tolerably displaced). In a registry setting, age and sex are recorded, thus the maturity of the bone might be considered—although the Müller classification does not include this consideration. Child-specific fracture patterns such as buckle and green-stick fractures and different injuries to the growth zone reflect the stability and outcome of the fracture. The importance of classifying child-specific fracture patterns for treatment and outcome remains to be proven, as stated in step 3 in the 3-phase validation concept of Audigè et al. (Audige et al. Citation2005). Although the PCCF was presented in 2006 (Slongo et al. Citation2006) and the Li-La classification in 2011 (Schneidmuller et al. Citation2011), the Müller classification is still used in the Fracture and Dislocation Registry at our hospital for both pediatric and adult fractures (Müller et al. Citation1990). However, we consider to also register the child-specific fracture pattern, which would result in a registration close to what has already been proposed by Slongo et al. (Slongo et al. Citation1995). The relatively few childhood fractures treated by each general orthopedic surgeon and the disadvantage of presenting 2 separate classification systems to the surgeons reporting to the Fracture and Dislocation Registry at our hospital makes the introduction of an additional child-specific classification system less appropriate (Meling et al. Citation2012).

In summary, reliable classification of pediatric long bone fractures is possible to perform, at group level (4 signs), according to a slightly adjusted Müller classification. However, the classification does not cover some important considerations needed for treatment and prognostic evaluation. Consequently, at least age and gender of the patient and child-specific pattern of the fracture should also be reported.

The expert reference coding by senior orthopedic surgeon Trygve Søvik MD is highly appreciated. The study was supported by a grant from the Stavanger Health Trust Research Council.

The study was designed by TM, KH, MA, AJA, and KS. Software preparation for the registration was done by KH. Data analysis was done by TM, MA, CHE, AJA, and KS. TM, MA, and KS wrote the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

- Audige L. Development and evaluation process of a pediatric long-bone fracture cassification proposal. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2004; 30: 248.

- Audige L, Bhandari M, Kellam J. How reliable are reliability studies of fracture classifications? A systematic review of their methodologies. Acta Orthop Scand 2004; 75: 184-94.

- Audige L, Bhandari M, Hanson B, Kellam J. A concept for the validation of fracture classifications. J Orthop Trauma 2005; 19: 401-6.

- Deakin DE, Crosby JM, Moran CG, Chell J. Childhood fractures requiring inpatient management. Injury 2007; 38: 1241-6.

- Efron B, Tibshirani, RJ. Confidence intervals based on bootstrap percentiles. In: An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1993: 168-76.

- Falissard B. Various procedures used in psychometry. CRAN 2009; Version 1.1. Avaliable at http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/psy/psy.pdf.

- Gartland JJ. Manangement of supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1959; 109: 145-54.

- Gwet KL. Handbook of inter-rater reliability Second edition ed. Advanced Analytics, LLC: Gaithersburg 2010.

- Karanicolas PJ, Bhandari M, Kreder H, Moroni A, Richardson M, Walter SD, . Evaluating agreement: conducting a reliability study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 3) 2009; 91: 99-106.

- Kreder HJ, Hanel DP, McKee M, Jupiter J, McGillivary G, Swiontkowski MF. X-ray film measurements for healed distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg Am 1996; 21: 31-9.

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33: 159-74.

- Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, Broderick JS, Creevey W, DeCoster TA, . Fracture and dislocation classification compendium–2007: Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification, database and outcomes committee. J Orthop Trauma 2007; 21: S1-133.

- Meling T, Harboe K, Soreide K. Incidence of traumatic long-bone fractures requiring in-hospital management: a prospective age- and gender-specific analysis of 4890 fractures. Injury 2009; 40: 1212-9.

- Meling T, Harboe K, Arthursson AJ, Soreide K. Steppingstones to the implementation of an inhospital fracture and dislocation registry using the AO/OTA classification: compliance, completeness and commitment. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2010; 18: 54.

- Meling T, Harboe K, Enoksen CH, Aarflot M, Arthursson AJ, Søreide K. How reliable and accurate is the AO/OTA comprehensive classification for adult long-bone fractures? J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012; 73 (1): 224-31.

- Müller ME, Nazarian S, Koch P, Schatzker J. The comprehensive classification of fractures of long bones. Springer-Verlag: Berlin 1990.

- Salter RB. Injuries involving the epiphyseal plate. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1963; 45: 587-622.

- Schneidmuller D, Roder C, Kraus R, Marzi I, Kaiser M, Dietrich D, . Development and validation of a paediatric long-bone fracture classification. A prospective multicentre study in 13 European paediatric trauma centres. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011; 12: 89.

- Sim J, Wright CC. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther 2005; 85: 257-68.

- Slongo T, Schaerli AF, Koch P, Bühler M. Klassifikation und Dokumentation der Frakturen im Kindesalter- Pilotstudie der internationalen Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kindertramatologie. Zentralbl Kinderchir 1995; 4: 157-63.

- Slongo T, Audige L, Schlickewei W, Clavert JM, Hunter J. Development and validation of the AO pediatric comprehensive classification of long bone fractures by the Pediatric Expert Group of the AO Foundation in collaboration with AO Clinical Investigation and Documentation and the International Association for Pediatric Traumatology. J Pediatr Orthop 2006; 26: 43-9.

- Slongo T, Audige L, Clavert JM, Lutz N, Frick S, Hunter J. The AO comprehensive classification of pediatric long-bone fractures: a web-based multicenter agreement study. J Pediatr Orthop 2007a; 27: 171-80.

- . Slongo T, Audige L, Lutz N, Frick S, Schmittenbecher P, Hunter J, Documentation of fracture severity with the AO classification of pediatric long-bone fractures. Acta Orthop 2007b; 78: 247-53.

- von Laer L, Gruber R, Dallek M, Dietz HG, Kurz W, Linhart W, . Classification and Documantation of Children’s Fractures. Eur J Trauma 2000; 26: 2-14.