Abstract

Background and purpose During the past decades, treatment of pediatric femoral fractures in Finland has changed from mostly non-operative to more operative. In this retrospective study, we analyzed the long-term results of treatment.

Patients and methods 74 patients (mean age 7 (0–14) years) with a femoral fracture were treated in Aurora City Hospital in Helsinki during the period 1980–89. 52 of 74 patients participated in this clinical study with a mean follow-up of 21 (16–28) years. Fracture location, treatment mode, time of hospitalization, and fracture alignment at union were assessed. Subjective assessment and range of motion of the hip and knee were evaluated. Leg-length discrepancy and alignment of the lower extremities were measured both clinically and radiographically.

Results Of the 52 children, 28 had sustained a shaft fracture, 13 a proximal fracture, and 11 a distal fracture. 44 children were treated with traction, 5 by internal fixation, and 3 with cast-immobilization. Length of the hospital treatment averaged 58 (3–156) days and the median traction time was 39 (3–77) days. 21 of the 52 patients had angular malalignment of more than 10 degrees at union. 20 patients experienced back pain. Limping was seen in 10 patients and leg-length discrepancy of more than 15 mm was in 8 of the 52 patients. There was a positive correlation between angular deformity and knee-joint arthritis in radiographs at follow-up in 6 of 15 patients who were over 10 years of age at the time of injury.

Interpretation Angular malalignment after treatment of femoral fracture may lead to premature knee-joint arthritis. Tibial traction is not an acceptable treatment method for femoral fractures in children over 10 years of age.

Femoral fractures account for approximately 2% of all childhood fractures. In most cases, the child must be hospitalized. Traditionally, these fractures have been treated with traction and/or casting (Aronson et al. Citation1987). The long hospital stay and rising healthcare costs popularized surgical treatment from the beginning of the 1990s (Reeves et al. Citation1990, Hughes et al. Citation1995, Hedin Citation2004, Hedin et al. Citation2004).

Although there have been numerous studies describing different operative treatment methods, there is still no consensus as to which method should be used (Sanders et al. Citation2001, Flynn and Schwend Citation2004, Hedin Citation2004, Anglen et al. 2005, Cummings Citation2005, Wright et al. Citation2005, Poolman et al. Citation2006).

Femoral fracture treatment may lead to various complications such as malunion, non-union, leg-length discrepancy, skin lesions, and nerve injuries (Yandow et al. Citation1999, Flynn and Schwend Citation2004, Anglen and Choi Citation2005). Persistent angular deformity of the lower limb may lead to premature arthritis (Eckhoff et al. Citation1994). There are guidelines on the magnitude of angular deformity that can correct spontaneously during further growth which change depending on the child’s age (Flynn and Skaggs Citation2010).

In this retrospective study, we evaluated the childhood femoral fractures in patients treated in Aurora Hospital, Helsinki, during the years 1980–89. This hospital was the primary treatment institution for pediatric trauma patients in Helsinki during the study period, although patients with multiple trauma were treated elsewhere. We assessed the long-term results after non-operative treatment of femoral fractures. This may serve as a baseline to which future long-term results of operative treatment methods can be compared.

Patients and methods

All 74 children under the age of 16 admitted to our hospital due to a femoral fracture and treated in the operation room during the years 1980–1989 were included in the study. Patients who were treated at the outpatient department were not included. Patient information, available for all patients, and the radiographs during the treatment and follow-up information from the patient files were obtained retrospectively.

A questionnaire was sent to all patients inviting them to participate in a clinical and radiographic follow-up-examination. 52 patients agreed to participate.

The questionnaire included patients’ asessment about perceived leg-length discrepancy, possible deformations, symptoms such as limb or back pain and limp, and whether they had been treated later for the same injury. The patients were also asked about their memory of and opinion of the treatment in childhood. At the clinical examination, the patient’s walking was evaluated. Any scars due to skeletal traction or operative treatment were identified. Possible limb-length discrepancy was measured by block test. The circumferences of the thigh and the calf were measured. Range of hip and knee motion of the knee and was estimated, together with stability of the knee and the patellofemoral joint.

A musculoskeletal radiologist (ML) retrospectively evaluated the radiographs obtained during the treatment. All radiographs were re-analyzed. For the final analysis only the last image at the end of the treatment was included. Angular deformities: varus/valgus and antecurvatum/recurvatum were analyzed from the AP- and lateral views respectively together with shortening.

During the final check-up the injured and the non-injured legs were evaluated from standing, weight-bearing radiographs of each leg separately, and a standing lateral view of each femur separately. Analog radiographs were taken in fluoroscopy control at a distance of 1.5 m on graduated-grid 35 × 43 cm films.

For length measurements, a long radio-opaque ruler was fixed to the leg. The images were evaluated for length of the extremities, and separately for the length of the femurs. For angle measurements of the coronal and lateral curves of the femurs, a manual goniometer was used. For both femurs, angular deformity in 2 planes was estimated (valgus/varus in the AP view and antecurvatum/recurvatum in the lateral view).

The radiographic mechanical axis angle was calculated according to Hagstedt et al. (Citation1980). For calculation of the mechanical axis, the center of the femoral head was defined by using Mose (1980) circles, the midpoint of the knee being defined by the center of the femoral condyles at the level of the top of the intercondylar notch. The angulation of the femoral diaphysis was measured by drawing a line through the midsection of the femoral diaphysis, in both AP and lateral projections. The radiographs were also analyzed for signs of osteoarthritis according to a 3-point scale (normal = 0; joint space narrowing = grade 1; osteophytes, cysts, or erosions = grade 2).

The ethics committee of Helsinki University Central Hospital approved the study protocol (approval identification number 68/E7/2002).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 software. We used the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test for the differences and Spearman rho for correlations. The level of significance was set at 5%. To test the reliability

of angular deformity measurements, 5 radiographs were re-evaluated by the radiologist and 2 clinicians (SP and YN) independently. For these measurements, we calculated the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

Results

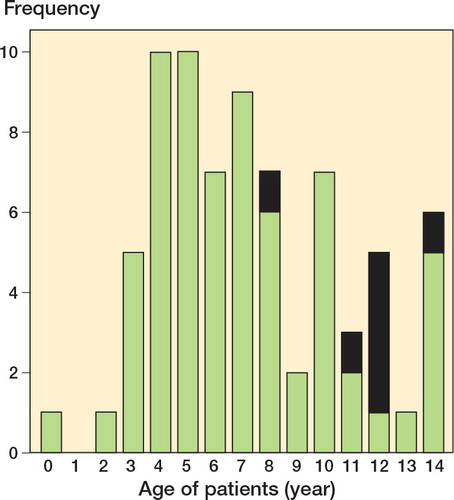

74 children (51 boys) with a femoral shaft fracture were treated during 1980–1989. The mean age of the children was 7 (0–14) years (). The most common etiology was a motor-vehicle accident (). The mean length of hospital treatment was 58 (3–156) days.

Figure 1. Age distribution of the 74 children treated for femoral fracture during the years 1980–89. Black color indicates patients with knee-joint arthritis at the final check.

Table 1. Characteristics of the 74 patients with femoral fractures treated in Aurora Hospital during the period 1980–89. Numbers in parentheses apply to the patients who attended the follow-up

Of the 74 patients, 52 returned the patient questionnaire and attended the clinical examination. Mean length of follow-up was 21 (16–28) years. 2 patients had died before the questionnaire was sent, 2 did not want to participate in the clinical examination, and 18 could not be reached. At the time of the final follow-up, the mean age of the patients was 28 (19–38) years. Of these 52 patients, 44 had been treated with traction with a median traction time of 39 (3–77) days, 5 by internal fixation, and 3 with casting. The memories of treatment were positive in 36 of the patients, negative in 3, and unspecified or non-existent in 13.

The subjective complaints in the patient questionnaire included back pain in 20 patients, leg-length discrepancy in 20, pain in the previously injured lower extremity in 14, deformities in 8, and perceived limping in 7 patients. There was no correlation between leg-length discrepancy and back pain (Spearman’s rho = 0.22; p = 0.1).

At the clinical follow-up, limping was seen in 5 of the 52 patients. A scar due to the treatment was found in 48 patients. The mean passive external rotation of the hip in the injured extremity was 40 (15–60) degrees and in the contralateral joint 45 (5–60) degrees (p = 0.006). The mean calf circumference was 37 (29–45) cm in the injured limb and 38 (30–44) cm in the uninjured limb, and the mean circumference of the thigh was 46 (34–56) cm in both limbs.

Clinically detectable leg-length discrepancy was found in 31 of the 52 patients. The injured limb was longer than the contralateral limb in 12 patients and shorter in 19 patients. The mean difference in length was 12 (5–30) mm. Leg-length discrepancy of ≥ 15mm was found in 8 patients. Of these patients, 6 had a radiographic leg-length discrepancy of the same amount.

In the radiographic evaluation, the mean length of the injured femur was 47 (38–53) cm and that of the uninjured femur was 47 (38–53) cm. The mean limb length was 84 (69–95) cm and 84 (69–94) cm, respectively. Radiographically, the mean difference in leg length was 11 (0–40) mm. There was a positive correlation between the clinical and the radiographic discrepancies in leg length (Spearman’s rho = 0.64; p < 0.001). There was a correlation between age at injury and final leg-length discrepancy (Spearman’s rho = 0.28; p = 0.05).

Angular deformity was determined in the radiographs at the final check. The mean varus-valgus deformity remodeled from 7 degrees after treatment to 5 degrees at follow-up. Mean antecurvatum-recurvatum deformity remained unchanged at 11 degrees. At the follow-up, angular deformity of > 10 degrees in the sagittal plane was seen in 21 of the 52 patients; 2 of these patients had angular deformity of > 10 degrees in the coronal plane also. All but 2 of the patients were treated with traction. The traction group had mean 6 degrees of malalignment in the coronal plane and 12 degrees of malalignment in the sagittal plane. In the group with non-traction the respective values were 5 degrees and 8 degrees (p = 0.2 and p = 0.3) ().

Table 2. The angular deformities and their remodeling from just after treatment to the final follow-up. Values are mean degrees, [95% CI] and (range)

Varus deformity was found in 30 patients after treatment and in 14 at the follow-up, valgus malalignment in 5 and 20, antecurvatum malalignment in 33 and 49, and recurvatum malalignment in 3 and 1, respectively (). Varus malalignment at the time of fracture union remained unchanged at follow-up in 12 patients, had remodeled into neutral position at follow-up in 10 patients, and had shifted into valgus in 8 patients. Valgus malalignment at the time of fracture union remained unchanged in 4 patients and had remodeled into normal alignment in 1 patient. Only 1 of the patients with healing in anatomical alignment in the frontal plane had varus malalignment at the time of follow-up. At the final follow-up, the mean antecurvatum was 11 (95% CI: 9–13) degrees for the injured femur and 8 (95% CI: 8–9) degrees for the contralateral limb (p = 0.001).

The interobserver rate (ICC) of the angular deformity measurements was 0.96 (p < 0.001). The maximum difference in measurements was 4 degrees.

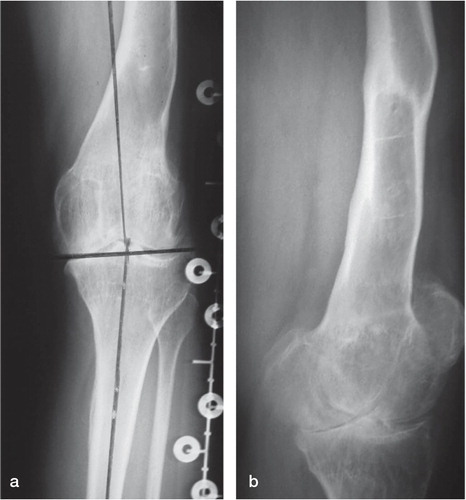

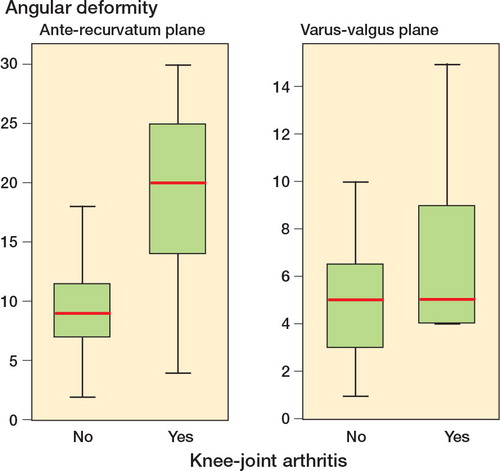

Knee arthritis was found in the injured limb in 6 patients and in the uninjured limb in 1 patient. Grade-I arthritis was found in 6 patients and grade-II arthritis was found in 1 patient (). The mean age of these patients at the time of injury was 12 (8–14) years, and at follow-up 34 (32–36) years (). There was premature knee-joint arthritis in 6 of 15 of patients aged 11 or more after the mean follow-up time of 22 (range: 20-24) years. The fracture location in these patients was proximal in 2, distal in 1, and mid-shaft in 4. All these patients were treated by tibial skeletal traction. There was more angular deformity found both in the varus-valgus (p = 0.1) and antecurvatum-recurvatum (p < 0.001) planes than in the patients with no knee arthritis (). There was a positive correlation between both varus-valgus deformity and antecurvatum-recurvatum deformity and knee-joint arthritis (Spearman’s rho = 0.57 and 0.44; p < 0.001 and p = 0.008, respectively). There was no correlation between leg-length discrepancy and knee arthritis (Spearman’s rho = 0.12; p = 0.4). Clinical anterior-posterior instability of the injured knee joint was found in 2 of the patients with knee arthritis.

Figure 2. Standing weightbearing radiographs of the left leg in a 36-year-old patient, who at the age of 14 sustained a distal femoral shaft fracture, which was treated with tibial skeletal traction. AP (a) and lateral view (b) show severe degenerative (grade-II) changes in the tibiofemoral joint.

Figure 3. Angular deformity (degrees) in patients with and without knee-joint arthritis at follow-up.

The results for the operatively treated 5 children were similar to those treated non-operatively.

Discussion

The long-term results of treatment of pediatric femoral shaft fractures have not been studied in depth. Irani et al. (Citation1976) reported a series of 85 children (aged 0–10 years) who were treated with spica casting and who had a mean follow-up of 6 years. None of them had angular or rotational deformities. Fuchs et al. (Citation2003) reported good results after non-operative treatment in children up to 6 years of age at a mean follow-up time of 7 years. Frech-Dörfler et al. (Citation2010) reported good results after a mean follow-up of 8 years in 22 pre-school children treated with immediate hip-spica casting. As far as we know there are no studies with longer follow-up times.

Long hospitalization including long periods in bed or in a wheelchair, and a parent having to stay at home from work, have been the main reasons to shift to mostly operative treatment (Sanders et al. Citation2001, Hedin Citation2004, Palmu et al. Citation2010). In the present study, with most children treated non-operatively, the mean stay in hospital was almost 2 months—and some of the children were even hospitalized for as much as 6 months. Wright et al. (Citation2005) reported a total stay in hospital of 4–5 days in a multicenter study comparing hip-spica casting and external fixation. Nascimento et al. (Citation2010) reported an average hospital stay of 9 days after treatment of femoral fractures with titanium elastic nailing.

Most of our patients were satisfied with their treatment in early adulthood. A third of the patients reported current back pain. According to a Finnish health survey, the prevalence of chronic lower back pain is 10% in men and 11% in women (Aromaa et al. Citation2004). Thus, the fracture sustained in childhood may be related to back pain in our material. More than a third of the patients had noticed a leg-length discrepancy, and more than half had a clinical discrepancy (mean 12 mm) or a radiographic discrepancy (mean 11 mm). There was no statistically significant correlation between leg-length discrepancy and back pain. Harvey et al. (Citation2010) showed that a radiographic leg-length discrepancy of > 1cm was associated with bilateral knee arthritis and progressive arthritis of the shorter leg. We did not find any significant correlation between the leg-length discrepancy and knee-joint arthritis.

Children have a high remodeling potential, which helps in correcting post-traumatic angular deformity caused by fractures. Even 25 degrees of angulation in any plane can remodel satisfactorily (Wallace and Hoffman Citation1992). Flynn and Schwend (Citation2004) suggested that varus-valgus deformities are more likely to cause problems than are antecurvatum-recurvatum deformities. In the present study, there was more remodeling of varus-valgus deformities than of antecurvatum-recurvatum deformities. Interestingly, the remodeling in the frontal plane occurred more commonly into valgus. It is noteworthy that antecurvatum-recurvatum deformities in particular were statistically significantly associated with knee arthritis. The patients who had knee arthritis were slightly older than the average, which could indicate that their remodeling potential was already reduced. In patients aged 11 or more, 4 of 10 presented with premature knee-joint arthritis. Apparently the arthritis is premature; in a Finnish health examination survey, the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in patients less than 45 years of age was 0.3–0.4% (CitationKaila-Kangas 2007). Flynn and Skaggs (Citation2010) suggested that acceptable angulation in the age group > 11 years should not exceed 10 degrees anterior/posterior or 5 degrees varus/valgus. Our findings support these guidelines. Although children have a high remodeling potential, substantial angular deformities should not be tolerated in fracture treatment. Earlier studies have indicated that deformities may cause premature arthritis (Weber Citation1969, Verbeek et al. Citation1976, Eckhoff et al. Citation1994), although no clear evidence has been put forward previously.

In order to minimize the radiation load, no dedicated images of the femur or knee joint were obtained during the follow-up-study. Minor signs of osteoarthritis may therefore have been missed. As evaluation of the degree of osteoarthritis was based on full-length weight-bearing radiographs, we decided to use a rough 3-grade evaluation scale instead of a more detailed grading system such as that by Kellgren and Lawrence (Citation1957). It is noteworthy that several of the patients, who were young adults at the time of the final examination, showed signs of premature probably progressive osteoarthritis.

In summary, we found that traction or casting of femoral fractures in children less than 10 years of age is safe, and good long-term results can be expected. Children over 10 years of age had a high risk of residual angular deformity, which correlated with knee arthritis. In this age group, tibial skeletal traction should be avoided.

SP: planning of the study design, data collection and analysis, statistical analysis, and preparation of manuscript. ML: radiographic evaluation and preparation of manuscript. RP: planning of the study design and data collection. JP: planning of the study design and preparation of manuscript. YN: planning of the study design, data analysis, and preparation of manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

- Anglen JO, Choi L. Treatment options in pediatric femoral shaft fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2005;19:724-33

- Aromaa A, Koskinen S. Health and functional capacity in Finland. Baseline results of the health 2000 health examination survey. Publications of the National Public Health Institute, KTL B12/2004. http://www.terveys2000.fi/julkaisut/baseline.pdf

- Aronson DD, Singer RM, Higgins RF. Skeletal traction for fractures of the femoral shaft in children. A long-term study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1987;69:1435-9

- Cummings RJ. Paediatric femoral fracture. Comment. Lancet 2005;365:1116-17

- Eckhoff DG, Kramer RC, Alongi CA, VanGeven DP. Femoral anteversion and arthritis of the knee. J Ped Orthop 1994;14:608-10

- Flynn JM, Schwend RM. Management of pediatric femoral shaft fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2004;12:347-59

- Flynn JM, Skaggs DL. Femoral shaft fractures. Chapt. 22 in: Rockwood and Wilkins’ Fractures in Children, 7th ed. (eds. Beaty and Kasser). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Philadelphia PA. 2010: 797-841.

- Frech-Dörfler M, Hasler CC, Häcker FM. Immediate hip spica for unstable femoral shaft fractures in preschool children: still an efficient and effective option. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2010;20:1): 18-23.

- Fuchs M, Losch A, Noak E, Stürmer KM. Long-term results after conservative treatment of pediatric femoral shaft fractures. Orthopade 2003;32(12): 1136-42.

- Hagstedt B, Norman O, Olsson TH, Tjörnstrand B. Technical accuracy in high tibial osteotomy for gonarthrosis. Acta Orthop Scand 1980;51:963-70

- Harvey WF, Yang M, Cooke T DV, . Association of Leg-Length Inequality With Knee Osteoarthritis. A cohort study. Ann Int Med 2010;152:287-95

- Hedin H. Surgical treatment of femoral fractures in children. Acta Orthop 2004;75(3): 231-40.

- Hedin H, Borgquist L, Larsson S. A cost analysis of three methods of treating femoral shaft fractures in children. Acta Orthop 2004;75(3): 241-8.

- Hughes BF, Sponseller PD, Thompson JD. Pediatric femur fractures: Effects of spica cast treatment on family and community. J Ped Orthop 1995;15(4): 457-60.

- Irani RN, Nicholson JT, Chung SM. Long-term results in the treatment of femoral-shaft fractures in young children by immediate spica immobilization. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1976;58(7): 945-51.

- Kaila-Kangas L, ed.?Musculoskeletal Disorders and Diseases in Finland. Results of the Health 2000 Survey. Publications of the National Public Health Institute, B 25 / 2007. http://www.ktl.fi/portal/2920

- Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 1957;16(4): 494-502.

- Mose K. Methods of measuring in Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease with special regard to the prognosis. Clin Orthop 1980(150):103-9

- Nascimento FP, Santini C, Akkari M. Waisberg G, d Reis Braga S, M. de Barros, Fucs PM. Short hospitalization period with elastic stable intramedullary nails in the treatment of femoral shaft fractures in school children. J Child Orthop 2010;4:53-60

- Palmu S, Paukku R, Peltonen J, Nietosvaara Y. Treatment injuries are rare in children’s femoral fractures. Compensation claims submitted to the Patient Insurance Center in Finland. Acta Orthop 2010;81(6): 715-8.

- Poolman RW, Kocher MS, Bhandari M. Pediatric femoral fractures: A systematic review of 2422 cases. J Orthop Trauma 2006;20(9): 648-54.

- Reeves RB, Ballard RI, Hughes JL. Internal fixation versus traction and casting of adolescent femoral shaft fractures. J Pediatr Orthop 1990;10(5): 592-5.

- Sanders JO, Browne RH, Mooney JF, . Treatment of femoral fractures in children by pediatric orthopedists: Results of a 1998 survey. J Ped Orthop 2001;21:436-41

- Verbeek H OF, Bender J, Sawdis K. Rotation of the femur after fractures of the femoral shaft in children. Injury 1976;8:43-8

- Wallace ME, Hoffman EB. Remodelling of angular deformity after femoral shaft fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1992;74:765-9

- Weber BG. Fractures of the femoral shaft in children. Injury 1969;1:65-8

- Wright JG, Wang E EL, Owen JL, . Treatments for paediatric femoral fractures: a randomised trial. Lancet 2005;365:1153-8

- Yandow S, Archibeck M, Stevens P, Schultz R. Femoral-shaft fractures in children: A comparison of immediate casting and traction. J Pediatr Orthop 1999;19(1): 55-9.