Abstract

Background and purpose Short femoral stems have been introduced in total hip arthroplasty in order to save proximal bone stock. We hypothesized that a short stem preserves periprosthetic bone mineral density (BMD) and provides good primary stability.

Methods We carried out a prospective cohort study of 30 patients receiving the collum femoris-preserving (CFP) stem. Preoperative total hip BMD and postoperative periprosthetic BMD in Gruen zones 1–7 were investigated by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA), stem migration was analyzed by radiostereometric analysis (RSA), and the Harris hip score (HHS) was determined.

Results 2 patients were excluded intraoperatively and 1 patient was revised due to a deep infection, leaving 27 patients for analysis. The mean HHS increased from 49 (24–79) preoperatively to 99 (92–100) after 2 years. DXA after 1 year showed substantial loss of BMD in Gruen zone 7 (–31%), zone 6 (–19%), and zone 2 (–13%, p < 0.001) compared to baseline BMD determined immediately postoperatively. The bone loss in these regions did not recover after 2 years, whereas the more moderate bone loss in Gruen zones 1, 3, and 5 partially recovered. There was a correlation between low preoperative total hip BMD and a higher amount of bone loss in Gruen zones 2, 6 and 7. RSA showed minor micromotion of the stem: mean subsidence was 0.13 (95% CI: –0.28 to 0.01) mm and mean rotation around the longitudinal axis was 0.01º (95% CI: –0.1 to 0.39) after 2 years.

Interpretation We conclude that substantial loss in proximal periprosthetic BMD cannot be prevented by the use of a novel type of short, curved stem, and forces appear to be transmitted distally. However, the stems showed very small migration—a characteristic of stable uncemented implants.

Stable fixation and preservation of femoral bone stock is important in total hip arthroplasty (THA). Hip resurfacing theoretically provides the most marked preservation of the proximal femur, but femoral neck fractures, early loosening due to osteonecrosis, development of pseudotumours, and other complications have diminished the initial euphoria associated with this procedure (Lazarinis et al. Citation2008, Johanson et al. Citation2010). Short femoral stems provide the opportunity to avoid such resurfacing-specific complications while potentially saving more femoral bone stock than conventional femoral stems. Short femoral stems allow preservation of proximal bone stock (1) by subcapital resections of the femoral neck, and (2) putatively, by exerting more proximal load transfer than distally anchored, conventional stems. A study on a conventional uncemented stem indicated that the loss of periprosthetic bone mineral density (BMD) is less pronounced around smaller stems (Sköldenberg et al. Citation2006). However, little is known about the results after insertion of short femoral stems, and there have been very few investigations of periprosthetic BMD around short femoral stems.

BMD around both cemented and uncemented femoral stems decreases after conventional THA (Cohen and Rushton Citation1995, Aldinger et al. Citation2003). This loss in periprosthetic BMD is of concern. Most importantly, it has been suggested that implant loosening or periprosthetic fractures can be consequences of this remodeling of bone substance adjacent to uncemented or cemented femoral stems (Kroger et al. Citation1998, Kobayashi et al. Citation2000). The main reason for this loss of proximal BMD is stress shielding, brought about by the implant shifting load transfer from the proximal femur to the metadiaphyseal region (Oh and Harris Citation1978).

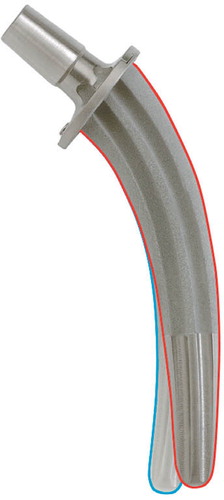

The collum femoris-preserving (CFP) stem (), introduced by Pipino and Calderale (Citation1987), combines a subcapital osteotomy with proposed proximal load transfer. Clinical and radiographic results published by the developer of the implant suggested good clinical performance of this stem, but significant loss to follow-up and the absence of precise measurement of implant migration and periprosthetic BMD call these reports into question. Recent studies have found BMD reduction in the proximal femur around the CFP stem (Gillies et al. Citation2007, Kress et al. Citation2012). However, this bone loss does not appear to influence clinical outcome in the medium term (Gill et al. Citation2008, Nowak et al. Citation2011). We therefore aimed at introducing the CFP stem with its purportedly superior properties in a prospective cohort study, and hypothesized that (1) loss of proximal periprosthetic BMD is reduced compared to conventional implants, and (2) early implant migration (suggestive of later loosening) is small.

Patients and methods

Study design and population

The study was designed as a prospective cohort study and consecutively included patients with primary osteoarthritis of the hip who were eligible for uncemented THA from March 2008 to March 2009. Inclusion criteria were radiographically verified osteoarthritis of the hip, age between 20 and 65 years, and a body weight below 100 kg. We aimed at investigating BMD changes of the healthy skeleton around the CFP stem; thus, exclusion criteria were inflammatory diseases (rheumatoid arthritis and comparable diseases) as diagnosed by ARA criteria, systemic glucocorticoid treatment, disabling diseases of the musculoskeletal system other than the hip, malignancy with ongoing or planned therapy, chronic infectious diseases, and osteoporosis (as determined by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA)). Further exclusion criteria were severe joint deformities jeopardizing standard operating technique, alcohol or drug addiction, and psychiatric disorders that endangered patient compliance.

30 patients (18 women) were included in the study over a 1-year period. Their mean BMI was 27 (20–35) kg/cm2. Mean age of the patients was 56 (42–65) years. 3 patients had to be excluded after the index procedure (2 received conventional straight femoral stems due to proximal femoral fissures that occurred during broaching for the CFP stem, and 1 patient was revised due to an early deep infection), leaving 27 patients for analysis by Harris hip score (HHS) and DXA. 1 patient received an implant where an insufficient number of tantalum markers had been inserted by the manufacturer, which made RSA impossible, leaving 26 patients for RSA analysis. No further patients were lost at the 2 year follow-up.

Ethical approval was obtained from the local ethics committee (Regionala Etikprövningsnämnden Uppsala; approval number 2007/105). Written informed consent regarding participation was obtained from all patients.

Implant and surgery

Surgery was performed by 1 of 2 surgeons (JM or NPH) using the instruments and implants provided by Waldemar Link GmbH & Co. KG (Hamburg, Germany). A transgluteal approach (Bauer et al. Citation1979) with release of the anterior third of the gluteus medius muscle from the tip of the greater trochanter was used. Subcapital resection of the collum femoris was performed in accordance with preoperative planning in all patients, thus retaining support by the femoral neck. Acetabular preparation and implantation of an uncemented cup followed standard procedures. A trocar awl was used to create a hole close to the calcar to accommodate the femoral guide, followed by opening of the femoral canal with a bone curette and determination of the stem size with a curved probe. Reamers of increasing sizes and available with 2 different curvatures (in order to accommodate variations in femoral anatomy) were used to compress the cancellous bone and a calcar reamer created a plane surface for the seating of the stem’s neckplate. A definite implant matching the size and curvature of the last reamer was inserted using a handle, and a metal head (28 mm) was connected to its trunion.

Tranexamic acid was used intravenously in order to reduce blood loss provided that no contraindications existed, as was perioperative intravenous antibiotic profylaxis with cloxacillin. Local infiltration anesthesia using ropivacain, ketorolac, and adrenalin was administered. Wound drains were not used. Low-molecular-weight heparin was administered for 2 weeks. Patients were mobilized on crutches, and immediate full weight bearing was encouraged.

Clinical outcome measures and radiography

The HHS was determined preoperatively and at follow-up visits 3, 12, and 24 months after surgery. Follow-up included anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the hip in all patients.

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA)

Preoperatively, the proximal femur on the diseased side was scanned with DXA (Prodigy; GE-Lunar, Madison, WI) in order to determine BMD (in g/cm2) for 2 standard proximal femur regions of interest (ROIs), the femoral neck (FN) and total hip (TH), and in order to calculate Z-scores, i.e. standard deviations of a weight-adjusted, age- and sex-matched reference population (of US-white caucasians) provided by the manufacturer.

The first postoperative measurement was performed during the first 2 postoperative days before mobilization of the patient, and it was determined as a baseline measurement. The hip implant software was used for postoperative periprosthetic BMD measurements adjacent to the CFP implant, i.e. the 7 Gruen zones. Further DXA measurements were done at scheduled follow-up after 3, 12, and 24 months, and duplicate measurements with repositioning between scans were undertaken as required in order to calculate the precision error. Long-term precision error for the equipment, expressed as CV% for a lumbar spine phantom, was less than 0.3% during the study period. The precision errors for duplicate measurements for the different Gruen zones were between 1.1 and 5.7 ().

Table 1. Precision of DXA measurements in all Gruen zones, with coefficients of variation

Radiostereometric analysis

The inserted stems were labeled preoperatively with 5 tantalum markers by the manufacturer. Additionally, during surgery 5 tantalum markers (diameter 1 mm) were inserted into the greater and lesser trochanter, and 1 additional marker was inserted into the femoral diaphysis distal to the tip of the prosthesis. Postoperatively, but before the patients were mobilized, simultaneous radiographs of the hip were taken using 2 X-ray tubes positioned at an angle of 40°. The RSA analysis software UMRSA (RSA Biomedical, Umeå, Sweden) was used in order to determine the rotation and translation of the calculated rigid body of the stem relative to the position of the rigid body derived from the tantalum markers in the femur. In addition, we calculated maximum total point motion (MTPM).

The precision of RSA measurements was determined by repeated examinations postoperatively according to standard procedures, and a 99% confidence interval was chosen as the value of precision () (CitationValstar et al. 2005). The baseline RSA investigation was performed within 2 days postoperatively, and follow-up investigations were performed after 3, 12, and 24 months. Mean errors of rigid body fitting and condition numbers were calculated in order to ensure marker stability and acceptable marker scatter over time; they were < 0.3 and < 107, respectively, in all cases.

Table 2. Precision error of RSA based on 99% precision intervals after repeated measurements

Statistics

The study had 2 primary endpoints: measurement of periprosthetic BMD and implant subsidence measured as translation along the y-axis. A power analysis indicated that 20 patients would be sufficient for detection of a decrease in periprosthetic BMD in Gruen zone 7 of one standard deviation and implant subsidence exceeding 2 mm—with a power of 80%, given a 2-tailed a = 0.05. A decrease in periprosthetic BMD of 1 standard deviation and subsidence exceeding 2 mm were considered clinically relevant. Changes in the remaining 6 Gruen zones, translation along and rotation around the remaining 5 axes in space, and correlation between BMD and implant migration were investigated in an exploratory fashion using post-hoc tests.

All variables were summarized using standard descriptive statistics such as frequencies, means, medians, and standard deviations. In accordance with the literature on BMD measurements, the precision of periprosthetic BMD measurements was determined by calculation of the coefficient of variation (CV%). In contrast, the precision of RSA measurements was determined as previously described (Kärrholm Citation1989). Briefly, the square root of squared differences between repeated measurements divided by n – 1 was multiplied by the appropriate t-value in order to obtain a 99% precision interval. BMD and RSA data were normally distributed and within-subjects effects were analyzed using a general linear model with a repeated-measures design and planned contrasts; the assumption of sphericity was determined by Mauchly’s test. If sphericity was violated, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied. The Bonferroni adjustment was used for post-hoc pairwise comparisons. Parametric correlation analyses were performed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The level of significance was set at ≤ 0.05 in all analyses.

Results

Clinical and radiographic outcome

Clinical outcome was excellent, with HHS increasing from 49 (24–79) to 99 (91–100) after 1 year and to 99 (92–100) after 2 years. On plain radiography, no signs of stem subsidence or rotation were visible in any patient after 2 years, as determined by 2 independent observers. In 10 cases, intramedullary pedestal formation adjacent to the distal tip of the stem was visible after 1 year. Plain radiography showed bone atrophy in the calcar region in 23 of 27 patients 2 years after surgery.

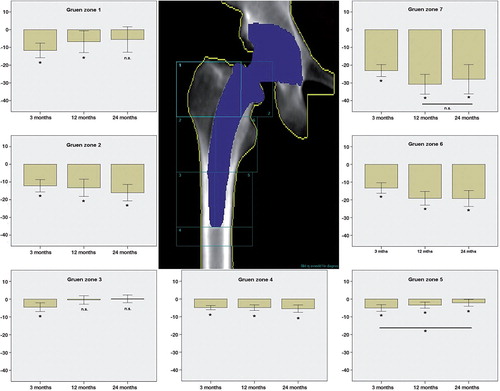

Decrease in periprosthetic BMD around the CFP stem

Preoperative BMD measurement of the proximal femur indicated that none of the patients suffered from low BMD, with Z-scores varying from –1.8 to 1.6 (mean –0.2). Comparison of postoperative BMD measurements with baseline data obtained immediately after surgery showed substantial bone loss in the proximal periprosthetic regions, with the most marked decrease in BMD being observed in Gruen zones 6 and 7 () one year after surgery. In Gruen zone 7, the decrease 1 year after surgery was 31% (p < 0.001), whereas a decrease of 19% was seen in Gruen zone 6 after 1 year (p < 0.001). A statistically significant, albeit smaller decrease in periprosthetic BMD was also seen in Gruen zones 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 after 3 months and 12 months. The general pattern after 3 months and 1 year was that the most pronounced decrease in periprosthetic BMD occurred in the proximal regions, whereas the distal Gruen zones 3, 4, and 5 showed the lowest decrease in BMD.

Figure 2. Changes in periprosthetic BMD in all Gruen zones. The p-values are derived from a general linear model with a repeated-measures design (* p < 0.05; n.s.: not statistically significant compared to baseline or between the groups). Error bars show 95% CI.

2 years after insertion of the stem, periprosthetic bone loss remained substantial in Gruen zones 7 (28% reduction after 2 years; p < 0.001) and 6 (19% reduction after 2 years; p < 0.001), without any signs of recovery when compared with baseline values. In contrast, periprosthetic BMD did recover to baseline values in Gruen zones 1 and 3. A modest recovery was also found in Gruen zone 5, where the loss in BMD after 2 years was less pronounced than after 3 months (p = 0.04), although the reduction in BMD in this region after 2 years remained compared to baseline values (p = 0.03).

There was a moderate correlation between low total hip BMD preoperatively with a higher amount of bone loss in Gruen zone 2 (Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.6, p = 0.001), zone 6 (r = 0.5, p = 0.005), and zone 7 (r = 0.6, p = 0.003)—i.e. the Gruen zones with the most pronounced postoperative bone loss.

Migration pattern of the CFP stem

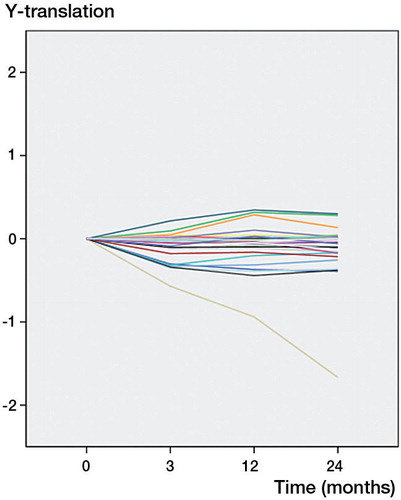

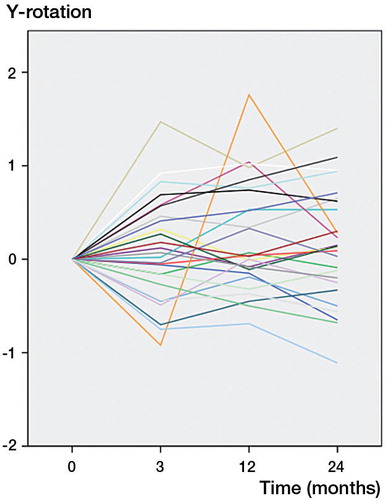

The translations along and rotations around the 3 axes were very small at all time points measured. The largest amplitudes were found for rotation around the y-axis, equivalent to slight stem retroversion, and for translation along the y-axis, representing stem subsidence, but the mean values for these micromotions were minor ( and and ). In addition, mean rotation around the z-axis, equivalent to varus/valgus tilt, was even smaller than the excursions mentioned above. No statistically significant change in stem subsidence occurred between any of the time points measured (p = 0.7 for 3 months vs. 12 months; p = 0.1 for 12 months vs. 24 months). Likewise, there was no significant change in rotation around the longitudinal axis (p = 1.0 for 3 months vs. 12 months; p = 0.2 for 12 months vs. 24 months), and no significant change in varus/valgus tilt (p = 0.3 for 3 months vs. 12 months; p = 0.1 for 12 months vs. 24 months) when comparing the different time points with each other.

Table 3. Stem migration after 3, 12, and 24 months

Figure 3. Migration of all individual components along the y-axis, representing stem subsidence measured in mm. Precision error = 0.09 mm. 1 stem continued to subside up to 2 years after surgery, but absolute subsidence was 1.67 mm and the patient was clinically asymptomatic.

Figure 4. Migration of all individual components around the y-axis, representing stem rotation measured in degrees. Precision error = 0.83°. The same stem that was found to subside more than average in Figure 3 showed an abnormal rotation pattern, but maximum rotation was 1.4°.

3 of 26 stems showed anteversion or retroversion above the precision error after 3 months. 2 years after surgery, 5 stems had rotated around this axis above the precision error, with a maximal rotation of 1.4°. Nine of 26 stems showed subsidence exceeding the precision error 3 months after surgery. Only 1 stem continued to subside and rotate up to 2 years after surgery; however, absolute subsidence and rotation at this time point were 1.67 mm and 1.4° respectively. There were no signs of stem loosening on plain radiography, and the patient had no clinical symptoms of loosening at any time ( and ). All other stems had stabilized after 1 year.

Discussion

Our main findings are that good primary stability is achieved using a novel hydroxyapatite-coated short femoral stem, but that proximal femoral bone loss is not avoided. Previous reports on the CFP stem had a number of deficiencies, i.e. large loss to follow-up (Pipino and Molfetta Citation1993), methodological problems related to RSA measurements (Röhrl et al. Citation2006), the absence of quantitative assessments of periprosthetic BMD (Briem et al. Citation2011), or combinations of such problems.

Periprosthetic BMD

Determination of periprosthetic BMD is important in characterization of the response of bone to the insertion of implants. Based on Wolff’s law of transformation, changes in periprosthetic BMD can allow certain conclusions on the vectors of load transfer around implants to be drawn: a loss in proximal periprosthetic BMD has been described for both cemented and uncemented femoral stems, suggestive of diaphyseal load transfer. The absence of such proximal bone loss in new types of implants would indicate that more proximal load transfer occurs, and such patterns of reduced proximal bone loss have in fact been described for extremely short uncemented stems (Albanese et al. Citation2009). In that study, higher absolute BMD values in the proximal medial regions were described when comparing an ultra-short femoral stem with a slightly longer one. 3 years after surgery, however, a substantial loss of BMD was found in the region representing the calcar even after the use of the ultra-short stem type.

Our findings of substantial bone loss around the CFP stem in the calcar region are strengthened by other studies on this type of stem using plain radiography or computer tomography-assisted bone densitometry. It has been described that the “[…] proximal part of the femur became relatively osteopenic” after insertion of the CFP stem , and that “[…] proximal cancellous [bone density] decreased progressively” from the first to the third year after surgery using this stem (Schmidt et al. Citation2011). However, to our knowledge, no other studies have investigated periprosthetic BMD around the CFP stem using the highly accurate DXA method.

Measurements of periprosthetic BMD around other uncemented stems have indicated that substantial bone loss regularly occurs in proximal regions. BMD around both cemented and uncemented femoral stems decreases after THA (Cohen and Rushton Citation1995, Aldinger et al. Citation2003). The most dramatic loss in BMD appears to occur during the first 3–6 months, after which a plateau (with annual losses comparable to those that take place during ageing) appears to be reached (Venesmaa et al. Citation2003). Most authors have found that there is no recovery of lost periprosthetic BMD, but a certain amount of recovery in the calcar region—albeit at a lower level—has been described in some cases (Karachalios et al. Citation2004). Loss of periprosthetic BMD has also been reported after revision THA using a long uncemented femoral stem (Sköldenberg et al. Citation2006).

The amount of bone loss in the most affected regions seems to be influenced by preoperative BMD in the hip. Our correlation analyses indicated that there was a correlation between low total hip BMD and increased loss of BMD in Gruen zones 2, 6, and 7. This is in accordance with the finding that patients with low preoperative BMD are prone to a higher degree of periprosthetic bone loss (Alm et al. Citation2009).

Taken together, the present literature on periprosthetic BMD indicates that loss of proximal femoral bone density occurs after the insertion of both short and long uncemented stems, and that no novel implant with reduced length has been convincingly shown to inhibit this seemingly uniform reaction of the proximal femur. Moreover, most authors have not found recovery of lost periprosthetic BMD within the first 2 years after surgery. However, this seemingly unavoidable proximal bone loss does not appear to jeopardize primary stem stability.

Primary stability

The migration of the CFP was very small with regard to subsidence, rotation along its longitudinal axis, and valgus/varus tilt (). Mean subsidence after 2 years was 0.13 mm for the CFP stem, which compares favorably with other uncemented stems. The Wagner-Cone prosthesis that was previously investigated at our institution showed a mean subsidence of 0.5 mm after 2 years (CitationStröm et al. 2006), and the CLS stem, also investigated at this institution, had subsided 1.42 mm after 2 years (Wolf et al. Citation2010). Mean rotation of the CFP stem amounted to 0.01° of retroversion after 2 years, with a maximum amplitude of 1.4°, which is less than the amount of retroversion measured for the Wagner-Cone prosthesis (0.81° of retroversion after 2 years) and considerably less than the 2.39° of retroversion measured for the CLS stem after 2 years (Wolf et al. Citation2010). Both the Wagner-Cone prosthesis and the CLS stem have been shown to be associated with low long-term revision rates in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register (SHAR Citation2010).

Studies on other uncemented stems and performed at other institutions have confirmed that the excursions of the CFP stem are rather small in comparison. The ABG stem showed 0.28 mm of subsidence with a maximal amplitude of 4.31 mm in 1 case (Thien et al. Citation2007), and the Taperloc stem coated with hydroxyapatite subsided 0.25 mm after 2 years (Boe et al. Citation2011).

The only other RSA study on the CFP prosthesis that is known to us also described stem retroversion, but with much greater amplitudes than those found in our series (Röhrl et al. Citation2006). The amount of stem subsidence described in that study is comparable to what we found. However, in the above study, only 13 of 26 implanted stems were evaluated by RSA, due to technical difficulties in visualizing tantalum markers. In contrast, of 26 patients eligible for RSA in the present study, all of them could be analyzed at all time points.

Limitations of the study

The present study was designed as a prospective cohort study; thus, there was no control group and we can only compare our findings on periprosthetic BMD and implant migration with other cohorts. A novel uncemented stem concept may follow different migration patterns than those described for cemented stems. However, RSA allows precise and reproducible measurements of implant migration, and results from different units and on different cohorts have been compared with each other previously (Kärrholm Citation1989). Moreover, the Wagner-Cone and CLS stems have already been investigated at our institution using identical technical equipment, thus allowing comparisons between groups.

Conclusion

The curved, hydroxyapatite-coated CFP stem gives good clinical results in the short term and has excellent primary stability. However, the use of this stem cannot avoid substantial bone loss in the proximal femur. Future follow-up of our cohort will reveal whether this bone loss is recovered in the medium term or whether the losses suffered are maintained.

SL: performed all follow-up investigations and analyzed BMD and RSA. HM: supervised periprosthetic BMD analysis. PM: supervised RSA. NPH: performed statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. Surgeries were performed by NPH and JM. All the authors were involved in writing of the final manuscript.

We thank Monika Gelotte for excellent technical assistance.

NPH has received institutional support or lecturer’s fees from several ortho- paedic implant manufacturers including Link Sweden AB. Link Sweden AB was, however, not involved in either study design, data analysis or preparation of the present manuscript.

- Albanese CV, Santori FS, Pavan L, . Periprosthetic DXA after total hip arthroplasty with short vs. ultra-short custom-made femoral stems: 37 patients followed for 3 years. Acta Orthop 2009;80 (3): 291-7.

- Aldinger PR, Sabo D, Pritsch M, . Pattern of periprosthetic bone remodeling around stable uncemented tapered hip stems: a prospective 84-month follow-up study and a median 156-month cross-sectional study with DXA. Calcif Tissue Int 2003;73:2): 115-21.

- Alm JJ, Makinen TJ, Lankinen P, . Female patients with low systemic BMD are prone to bone loss in Gruen zone 7 after cementless total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2009;80(5): 531-7.

- Bauer R, Kerschbaumer F, Poisel S, Oberthaler W. The transgluteal approach to the hip joint. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1979;95(1-2): 47-9.

- Boe BG, Rohrl SM, Heier T, . A prospective randomized study comparing electrochemically deposited hydroxyapatite and plasma-sprayed hydroxyapatite on titanium stems. Acta Orthop 2011;82(1): 13-9.

- Briem D, Schneider M, Bogner N, . Mid-term results of 155 patients treated with a collum femoris preserving (CFP) short stem prosthesis. Int Orthop 2011;35(5): 655-60.

- Cohen B, Rushton N. Accuracy of DEXA measurement of bone mineral density after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1995;77(3): 479-83.

- Gill IR, Gill K, Jayasekera N, Miller J. Medium term results of the collum femoris preserving hydroxyapatite coated total hip replacement. Hip Int 2008;18(2): 75-80.

- Gillies RM, Kohan L, Cordingley R. Periprosthetic bone remodelling of a collum femoris preserving cementless titanium femoral hip replacement. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 2007;10(2): 97-102.

- Johanson PE, Fenstad AM, Furnes O, . Inferior outcome after hip resurfacing arthroplasty than after conventional arthroplasty. Evidence from the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA) database, 1995 to 2007. Acta Orthop 2010;81(5): 535-41.

- Karachalios T, Tsatsaronis C, Efraimis G, . The long-term clinical relevance of calcar atrophy caused by stress shielding in total hip arthroplasty: a 10-year, prospective, randomized study. J Arthroplasty 2004;19(4): 469-75.

- Kärrholm J. Roentgen stereophotogrammetry. Review of orthopedic applications. Acta Orthop Scand 1989;60(4): 491-503.

- Kobayashi S, Saito N, Horiuchi H, . Poor bone quality or hip structure as risk factors affecting survival of total-hip arthroplasty. Lancet 2000;355(9214): 1499-504.

- Kress AM, Schmidt R, Nowak TE, . Stress-related femoral cortical and cancellous bone density loss after collum femoris preserving uncemented total hip arthroplasty: a prospective 7-year follow-up with quantitative computed tomography. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2012;132(8): 1111-9.

- Kroger H, Venesmaa P, Jurvelin J, . Bone density at the proximal femur after total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 1998(352):66-74

- Lazarinis S, Milbrink J, Hailer NP. Avascular necrosis and subsequent femoral neck fracture 3.5 years after hip resurfacing: a highly unusual late complication in the absence of risk factors--a case report. Acta Orthop 2008;79(6): 763-8.

- Nowak M, Nowak TE, Schmidt R, . Prospective study of a cementless total hip arthroplasty with a collum femoris preserving stem and a trabeculae oriented pressfit cup: minimun 6-year follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2011;131(4): 549-55.

- Oh I, Harris WH. Proximal strain distribution in the loaded femur. An in vitro comparison of the distributions in the intact femur and after insertion of different hip-replacement femoral components. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1978;60(1): 75-85.

- Pipino F, Calderale PM. Biodynamic total hip prosthesis. Ital J Orthop Traumatol 1987;13(3): 289-97.

- Pipino F, Molfetta L. Femoral neck preservation in total hip replacement. Ital J Orthop Traumatol 1993;19(1): 5-12.

- Röhrl SM, Li MG, Pedersen E, . Migration pattern of a short femoral neck preserving stem. Clin Orthop 2006(448):73-8

- Schmidt R, Gollwitzer S, Nowak TE, . Periprosthetic femoral bone reaction after total hip arthroplasty with preservation of the collum femoris: CT-assisted osteodensitometry 1 and 3 years postoperatively. Orthopade 2011;40(7): 591-8.

- SHAR. Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Annual Report 2010. http://www.shpr.se/Default.aspx

- Sköldenberg OG, Boden HS, Salemyr MO, . Periprosthetic proximal bone loss after uncemented hip arthroplasty is related to stem size: DXA measurements in 138 patients followed for 2-7 years. Acta Orthop 2006;77(3): 386-92.

- Ström H, Kolstad K, Mallmin H, . Comparison of the uncemented Cone and the cemented Bimetric hip prosthesis in young patients with osteoarthritis: an RSA, clinical and radiographic study. Acta Orthop 2006;77(1): 71-8.

- Thien TM, Ahnfelt L, Eriksson M, . Immediate weight bearing after uncemented total hip arthroplasty with an anteverted stem: a prospective randomized comparison using radiostereometry. Acta Orthop 2007;78(6): 730-8.

- Valstar ER, Gill R, Ryd L, . Guidelines for standarization of radiostereometry (RSA) of implants. Acta Orthop 2005;76(4): 563-72.

- Venesmaa PK, Kroger HP, Jurvelin JS, . Periprosthetic bone loss after cemented total hip arthroplasty: a prospective 5-year dual energy radiographic absorptiometry study of 15 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 2003;74(1): 31-6.

- Wolf O, Mattsson P, Milbrink J, . Periprosthetic bone mineral density and fixation of the uncemented CLS stem related to different weight bearing regimes: A randomized study using DXA and RSA in 38 patients followed for 5 years. Acta Orthop 2010;81(3): 286-91.