Abstract

Background and purpose Blood loss after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) may lead to anemia, blood transfusions, and increased total costs. Also, bleeding into the periarticular tissue may cause swelling and a reduction in quadriceps strength, thus impairing early functional recovery. In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, we analyzed the possible effect of fibrin sealant on blood loss and early functional recovery in a fast-track setting.

Methods 24 consecutive patients undergoing bilateral simultaneous TKA were included. 10 mL of fibrin sealant (Evicel) was sprayed onto one knee whereas the contralateral knee had saline. Drain output, the primary outcome, was measured from knee drains removed exactly 24 h after surgery. Secondary outcomes (knee swelling, pain, strength of knee extension, and range of movement (ROM)) were evaluated up to 21 days after surgery.

Results The drain output in knees treated with fibrin sealant and placebo was similar (582 mL and 576 mL, respectively). Likewise, no statistically significant differences were found between groups regarding swelling, pain, strength of knee extension, and ROM.

Interpretation Fibrin sealant as a local hemostatic in TKA showed no benefit in reducing drain output or in facilitating early functional recovery when used with a tourniquet, tranexamic acid, and a femoral bone plug.

Fast-track surgery is a dynamic multimodal regimen to reduce morbidity and mortality, to increase patient satisfaction, and to reduce the convalescence period postoperatively—i.e. to facilitate more rapid achievement of functional milestones (Husted et al. 2008, 2011, 2012, Kehlet Citation2011). Some of the cornerstones are reduction of pain and early mobilization, both of which are prerequisites for early achievement of functional discharge criteria (Husted et al. 2008). Previous studies have shown a reduction in quadriceps strength following TKA by up to 80%, which is related to postoperative swelling of the knee (Mizner and Snyder-Mackler Citation2005, Holm et al. Citation2010). This swelling is due to perioperative bleeding and edema. Blood loss causes anemia and fatigue, and may result in extended length of stay in hospital (LOS) (Husted et al. 2008), blood transfusion(s), and increased total costs. Thus, reducing periarticular swelling and blood loss may facilitate early functional recovery.

Several approaches to reducing blood loss and swelling have been investigated, including local application of fibrin sealant topically. 4 studies have evaluated the hemostatic effect of reducing blood loss, all in unilateral TKA. 2 studies used drain output as an outcome parameter (Levy et al. Citation1999, Wang et al. Citation2001) and 2 studies used Nadler’s formula (Nadler Citation1962) to estimate blood loss as an outcome parameter (Everts et al. Citation2007, McConnell et al. 2011). All 4 studies used a tourniquet to reduce intraoperative bleeding, whereas other evidence-based approaches to minimizing blood loss such as tranexamic acid (Zhang et al. Citation2012) or plugging of the femoral canal (Kumar et al. Citation2000) were not used. The study by McConnell et al. (2011) was a 3-arm study with fibrin sealant, tranexamic acid, and placebo, but not in combination. Also, the 4 studies focused on physiological considerations and the consequences of a reduced hemoglobin concentration without including secondary functional outcome parameters such as swelling, strength, range of movement (ROM), or pain—except Everts et al. (Citation2007), who included ROM. We therefore evaluated the potential effects of fibrin sealant (1) as an adjuvant to other evidence-based regimens (tranexamic acid, plugging of the intramedullary femoral canal) in reducing blood loss, and (2) as a facilitator of early functional recovery.

Patients and methods

24 patients operated with bilateral simultaneous (sequential) total knee arthroplasty (TKA) were included in this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, in a fast-track setup where we concentrated on optimized logistics and evidence-based clinical features (Husted et al. 2008). Eligible participants were adults over 18 years of age with symptomatic and radiographic bilateral knee osteoarthritis and without any history of or clinical findings of heart disease. The patients had to be able to speak and understand Danish, and had to be able to give informed consent. Patients were excluded on the criteria of abuse of alcohol or medicines, when allergic to Evicel or local anesthetic, and when being treated with opioids or glucocorticoids on a daily basis.

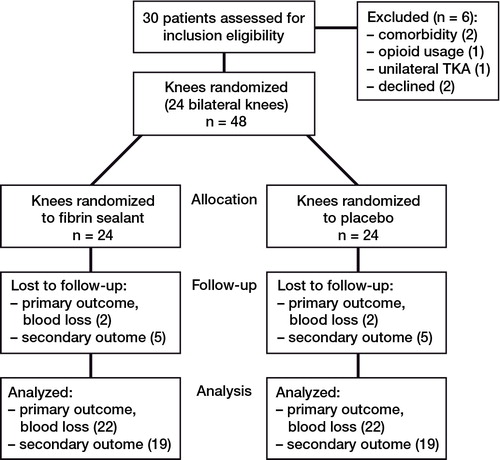

The study took place at Hvidovre University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark. It was performed between August 1, 2010 and September 1, 2011. During this 13-month period, 30 patients were assessed for inclusion eligibility and 4 could not be included due to comorbidity (2 patients), daily usage of opioids (1 patient), or change of surgery to unilateral TKA (1 patient). 2 other patients had no interest in participating. All 24 of the remaining patients received the intended treatment. Median age was 65 (33–81) years and 11 patients were women (). 2 of the 24 patients who were included did not undergo any evaluation of the primary outcome due accidental removal of the knee drains by the patients themselves. Altogether, 5 patients did not have all secondary outcomes assessed (Figure).

Table 1. Demographic data. Values are median (range)

The patients underwent arthroplasty with 2 identical prostheses for each individual (AGC or Vanguard ROCC; Biomet, Warsaw, IN). The left side was always operated on first. By using opaque sealed envelopes, left knees were randomized to either fibrin sealant (active treatment) or saline (placebo), with the opposite on the contralateral knee. The randomization key was computer-generated using an online randomization tool (www.randomization.com).

All patients received preoperative cefuroxime (1.5 g intravenously) and tranexamic acid (0.5 g 10 min before inflation of the tourniquet (100 mmHg above the systolic pressure) on the first knee followed by 0.5 g after deflation of the tourniquet, and before inflation of the tourniquet on the second knee). A midline skin incision with a medial parapatellar approach was used. The femoral canal was closed using an autologous bone plug and one intraarticular drain (passive) was installed in each knee.

Consort flow diagram of 24 bilateral total knee replacements randomized in the study (n = 48 total knee replacements).

After placement of the knee prosthesis, pulse-lavage was applied with 1 L of saline in which 240 mg gentamicin had been dissolved. Local infiltration analgesia (LIA) with 150 mL ropivacaine (0.2%) was used during surgery (Andersen et al. 2008). With the tourniquet still inflated, 10 mL of fibrin sealant (Evicel) was sprayed onto all instrumented cut surfaces (not covered by prosthetic components) and soft tissues, including the parts of the knee joint capsule that could be reached. Fibrin sealant (Evicel) is a two-component substance consisting of human thrombin and fibrinogen/fibronectin. Fibrinogen is a soluble plasma glycoprotein that is converted by thrombin into fibrin when mixed and sprayed onto the surface of bone and tissue (Dhillon Citation2011). In conjunction with platelets, fibrin forms a hemostatic plug or clot over the wound site. A drain was applied intraarticularly, and closure was performed, after which the tourniquet was deflated. There was a time interval of about 10 min from application to deflation of the tourniquet. This procedure was chosen to allow formation of fibrin clots and reduce the risk of immediate flushout of the fibrin sealant due to the hyperemia following tourniquet deflation. For each knee, drains were removed after exactly 24 h.

All patients were operated in spinal anesthesia with 3.0 mL plain bupivacaine (0.5%). A light sedation was offered with propofol (1–3 mg/kg/h). A standardized program in the operating theater was followed, including fluid administration (Holte el al. 2007) and SAGM transfusion if hemoglobin was less than 6.0 mmol/L. A standardized blood-transfusion protocol was followed during hospitalization (for a drop in postoperative hemoglobin of more than 25% relative to the preoperative level plus clinical symptoms of anemia).

Following discharge from the postoperative acute ward and arrival at the ward, the patients were encouraged to mobilize with the help of a physiotherapist or nurse within 2–4 h. Afterwards, they received physiotherapy once or twice daily until discharge. Pain treatment consisted of multimodal opioid-sparing oral analgesia (gabapentin (300 + 600 mg), celecoxib (200 mg × 2), paracetamol Retard (2 g × 2), and opioids (morphine) only upon request with a VAS pain score on activity of > 5). The fast-track setup involves a homogenous ward with only arthroplasty patients, regular staff, high continuity, functional discharge criteria, and supply of preoperative information including expected LOS (Husted et al. Citation2010).

Data collection was performed by staff who were blinded regarding which side had the active treatment, and all secondary outcomes were measured by an experienced physiotherapist who was also blinded. The primary outcome was blood loss, measured as the drain output from each knee 24 h postoperatively. Thus, blood loss was measured once per group, and there is therefore no multiplicity issue in the primary endpoint. Secondary outcomes were pain, ROM, swelling, and strength evaluated for each knee. Baseline values for the secondary outcomes were measured by the physiotherapist before the operation. After surgery, and before the first daily mobilization, pain and swelling were measured until the third postoperative day. The swelling was quantified by measuring the circumferences 1 cm proximal to the patella (Ross et al. 1998). Pain was scored by VAS, at rest and with a knee flexion of 45 degrees. Measurements regarding swelling and pain were repeated 7 days and 21 days after the operation.

Bilateral ROM and isometric strength were assessed on the mornings of days 3, 7, and 21 postoperatively. ROM was assessed with a goniometer (Lenssen et al. Citation2007). Isometric strength (in Nm) was estimated during an attempt to extend the knee from a 60-degree flexed position. Altogether, 5 attempts were done bilaterally and the highest value of the resulting force was chosen (Roy and Doherty Citation2004). Re-admissions during the first 90 days were assessed by examination of all patient files.

Statistics

Continuous data that were normally distributed are presented as mean (SD). Comparisons between groups were performed using Student’s t-test. If not normally distributed, data are presented as the median with interquartile range. These data were compared using the Wilcoxon signed ranks test. Distributions of data for the individual parameters were assessed by Q-Q plots and the Shapiro-Wilk test. Binomial data are presented as proportions and percentages. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used SPSS version 20 and Excel software for the statistical analyses.

An a priori sample size calculation with a difference in drain output of 300 (SD 350) mL between knees being considered to be a clinically relevant difference revealed that 22 knees in each group would be needed to show significance. This calculation was done using 80% power and a significance level of 5%. In this study, we included 24 knees in each group to account for loss to follow-up. Following a change in statistical approach—from originally using unpaired statistics to using paired statistics—we performed a recalculation of the sample size required based on the premises of paired comparisons (Park et al. Citation2010). This showed 13 patients, i.e. 26 knees. However, our results are still based on 24 patients (48 knees).

Ethics

The study was approved by the local ethics committee (H-A-2009-69) and was registered by Clinical Trials (NCT01472913). It was carried out in line with the Helsinki Declaration.

Results

No statistically significant difference in output from drains 24 h postoperatively was seen with fibrin sealant and placebo (p = 0.9). Mean output from drains for the fibrin sealant group was 582 (SD 328) mL, and for the placebo group it was 576 (SD 289) mL. The mean difference between groups was 6 (95% CI: –169 to 180) mL.

No statistically significant differences between fibrin-treated knees and placebo-treated knees were found regarding swelling, strength, ROM, or pain (). Median LOS was 3 days (the shortest possible LOS due to the schedule of testing). 1 patient underwent re-admission due to pneumonia at day 6 and 1 patient had a “suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction” (SUSAR) on day 2, which was reported to the Danish Medicines Agency due to the protocol and procedures of reporting. The patient was diagnosed by CT scan to have a thrombosis of 4 × 4 cm in vena cava superior, causing transient hemodynamic instability.

Table 2. Swelling in 19 patients (circumference (cm), postoperative strength (Nm/kg), ROM (degrees), and pain (VAS))

Discussion

We found no effect of fibrin sealant in reducing blood loss, measured as drain output at 24 h. Also, no effect of fibrin sealant was found on postoperative strength of knee extension, swelling, ROM, or pain. These negative results contrast with the positive results reported in 4 previous studies (Levy et al. Citation1999, Wang et al. Citation2001, Everts et al. Citation2007, McConnell et al. 2011). A reduction in blood loss of 224 mL after 12 h and 518 mL after 24 h has been measured in drains (Levy et al. Citation1999, Wang et al. Citation2001) and 374 mL has been calculated as blood loss after 48 h (McConnel et al. 2011). Everts et al. (Citation2007) found a reduction in the amount of blood transfusion of 0.35 U and a reduction in the difference between preoperative and postoperative hemoglobin (0.5 g/dL) in patients treated with fibrin sealant. They also found an improved ROM of 13 degrees on day 5 postoperatively. As earlier studies have evaluated drain output up to 24 h after operation, we chose the same period, and to have a similar setup except for the use of tranexamic acid and a femoral bone plug. Also, the exact length of time that fibrin sealant is effective locally is not known, but any effect is assumed to be relatively short-lived.

Regarding the secondary outcomes, strength and swelling have been shown to be inversely related, as measured on postoperative days 2–4 (Holm et al. Citation2010). We therefore chose to measure secondary outcomes on a daily basis in the postoperative phase, and also the possible normalization in the late postoperative phase (day 21).

Differences in the setup may account for the variation in the primary parameter outcome, as the present study has been the only one to include tranexamic acid for reduction of blood loss. This may have reduced blood loss on both sides in our bilateral setup to the extent that potential effects from the fibrin sealant became inferior to the reduction in blood loss caused by tranexamic acid on its own. Drainage output at 24 h in the present study was around 580 mL, as compared to 878 mL (Levy et al. Citation1999) and 408 mL after 12 h (Wang et al. Citation2001). The different outcomes may also have been due to the plugging of the femoral canal, which would be expected to reduce blood loss (Kumar et al. Citation2000). These procedures in our study are evidence-based and should be considered standard—if the ultimate goal is to minimize blood loss. Tranexamic acid and a bone plug are low-cost procedures. If the more expensive fibrin sealant is to be economically justified, an additional reduction equal to at least the cost of one blood transfusion should be observed. We therefore decided to use 300 mL, corresponding to 1 SAGM, as the least clinically significant difference in our study. Such a difference was not observed, as the 95% confidence interval for the treatment effect was (–169 to 180 mL), so there was no clinically significant effect.

Also, tourniquet time and tourniquet pressure should be kept short and low, and differences in these parameters may also influence the outcome. Fast-track management includes early mobilization and exercise, and the motion may also influence drainage output. Finally, the amount of fibrin sealant used may influence the drain output: amounts of 10–20 mL were used in the earlier studies, whereas we used 10 mL. The present study included an evaluation of the potential effect of fibrin sealant not only on blood loss but also on functional parameters important for early recovery. Another strength of the study was the bilateral setup where patients acted as their own controls, eliminating the bias introduced by inter-individual differences between patients, by different surgeons, different surgery times, variations in procedures, etc. The only disadvantage of the bilateral setting is the inability to evaluate potential differences in blood transfusion rates and amounts; however, as blood loss is similar for both knees, it seems unlikely that these would result in differences in blood transfusion. However, the use of knee drains has been criticized as falsely estimating blood loss: the hematocrit is reduced over time for the drain output within the first 24 h (Good et al. Citation2003), and the drain output does not include the additional bleeding into the soft tissues (hidden blood loss) (Foss and Kehlet Citation2006). With the present study setup, however, it seems unlikely (although not impossible) that the hematocrit would differ between knee drain output, or that more blood would be lost into the soft tissues on either side—thus allowing comparison of the outputs as a form of surrogate parameter for the actual blood loss. Furthermore, we evaluated functional outcomes for each knee and found no effect of fibrin sealant.

The study by Levy et al. (Citation1999) showed a reduction in blood loss and in hemoglobin for cemented TKA after 12 h. However, that study was a multicenter study with no description of some of the procedures (number of surgeons, potential differences in timing of mobilization). The study by Wang et al. (Citation2001) found reduced blood loss after treatment with fibrin sealant, and also a reduced blood transfusion rate. That study had methodological weaknesses, with electro-cauteric hemostasis (potentially uneven distribution in groups), 5 different types of prostheses, and several surgeons. The only study to include functional testing was the one by Everts et al. (Citation2007), which tested ROM with a focus on arthrofibrosis. The study by McConnell et al. (2011) found a reduced demand for blood transfusion and a reduced difference in pre- and postoperative hemoglobin, but it was flawed by the simultaneous use of fibrin sealant and autologous platelet gel with the purpose of reducing the bleeding, thus making contributions from each drug impossible to define.

The lack of any effect on blood loss in our study was possibly due to the reactive hyperemia generated immediately after releasing the tourniquet, which may have flushed out the fibrin sealant, even though the tourniquet was left inflated during closure of the wound (approximately 10 min) to allow formation of clots. This explanation is supported by the clinical observation of a viscous blood substance in the drain bags on the fibrin-treated side. The time period from application of the sealant to deflation of the tourniquet may have influenced the outcome. But as application of the fibrin sealant is the last maneuver before starting closure of the wound—and given that the tourniquet can be removed at the latest when the closure has finished—this is the longest period allowed for the sealant to work before deflation. We assume that the time of closure was fairly constant due to the surgery being performed in all cases by one experienced surgeon. We cannot rule out a possible effect of fibrin sealant when not using a tourniquet (thus, without any resulting hyperemia).

Regarding the patient reported to the Danish Medicines Agency with the CT-verified thrombosis in vena cava superior, this incident did not lead to any further request for investigation. We consider that it was a coincidence unrelated to the locally applied fibrin sealant.

In conclusion, we found no benefit of using fibrin sealant in TKA based on drain output, in a fast-track setup using a tourniquet and evidence-based clinical features such as tranexamic acid and plugging of the femoral canal to reduce blood loss.

All authors were involved in the study setup, interpretation of data, and revision of the manuscript. CS collected and interpreted data and wrote the first draft. BH collected data and performed physical testing. AT and TL collected data, interpreted data, and assisted in statistical analysis. LG-L collected data. HK interpreted data and was the academic supervisor. HH operated the patients, interpreted data, and was the clinical supervisor.

The study drug Evicel was sponsored by Johnson and Johnson Medical Ltd., Livingston, West Lothian, UK. It is egistered in Scotland: No. SC 132162. We thank statisticians Steen Ladelund of Research Group Hvidovre Hospital and Oejvind Jans of Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark.

No competing interests declared.

- Andersen LØ, Kristensen BB, Husted H, . Local anaesthetics after total knee arthroplasty: intraarticular or extraarticular administration? A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Acta Orthop 2008;79(6): 800-5.

- Dhillon S. Fibrin sealant (evicel® [quixil®/crosseal™]): a review of its use as supportive treatment for haemostasis in surgery. Drugs 2011;71(14): 1893-915.

- Everts PA, Devilee RJ, Oosterbos CJ, . Autologous platelet gel and fibrin sealant enhance the efficacy of total knee arthroplasty: improved range of motion, decreased length of stay and a reduced incidence of arthrofibrosis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2007;15(7): 888-94.

- Foss NB, Kehlet H. Hidden blood loss after surgery for hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006;88(8): 1053-9.

- Good L, Peterson E, Lisander B. Tranexamic acid decreases external blood loss but not hidden blood loss in total knee replacement. Br J Anaesth 2003;90(5): 596-9.

- Holm B, Kristensen MT, Bencke J, . Loss of knee-extension strength is related to knee swelling after total knee arthroplasty. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010;91(11): 1770-6.

- Holte K, Kristensen BB, Valentiner L, . Liberal versus restrictive fluid management in knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind study. Anesth Analg 2007;105(2): 465-74.

- Husted H, Holm G, Jacobsen S. Predictors of length of stay and patient satisfaction after hip and knee replacement surgery Fast-track experience in 712 patients. Acta Orthop 2008;79(2): 168-73.

- Husted H, Hansen HC, Holm G, . What determines length of stay after total hip and knee arthroplasty? A nationwide study in Denmark. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010;130(2): 263-8.

- Husted H, Troelsen A, Otte KS, . Fast-track surgery for bilateral total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011;93(3): 351-6.

- Husted H, Jensen C, Solgaard S, Kehlet H. Reduced length of stay following hip and knee arthroplasty in Denmark 2000–2009: from research to implementation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2012;132(1): 101-4.

- Kehlet H. Fast-track surgery-an update on physiological care principles to enhance recovery. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2011;396(5): 585-90.

- Kumar N, Saleh J, Gardiner E, . Plugging the intramedullary canal of the femur in total knee arthroplasty: reduction in postoperative blood loss. J Arthroplasty 2000;15(7): 947-9.

- Lenssen AF, van Dam EM, Crijns YH, . Reproducibility of goniometric measurement of the knee in the in-hospital phase following total knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007;8(83

- Levy O, Martinowitz U, Oran A, . The use of fibrin tissue adhesive to reduce blood loss and the need for blood transfusion after total knee arthroplasty. A prospective, randomized, multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1999;81(1580-8

- McConnell JS, Shewale S, Munro NA, . Reducing blood loss in primary knee arthroplasty: A prospective randomised controlled trial of tranexamic acid and fibrin spray. Knee. 2011 4 . (E-pub).

- Mizner RL, Snyder-Mackler L. Altered loading during walkingand sit-to-stand is affected by quadriceps weakness after total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Res 2005;23(1083-90

- Nadler SB. Prediction of blood volume in normal human adults. Surgery 1962;52(224-32

- Park M, Kim S, Chung C, . Statistical consideration for bilateral cases in orthopaedic research. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2010;92;1732-7

- Ross M, Worrell TW. Thigh and calf girth following knee injury and surgery. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1998;27(1): 9-15.

- Roy MA, Doherty TJ. Reliability of hand-held dynamometry in assessment of knee extensor strength after hip fracture. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2004;83(11): 813-8.

- Wang GJ, Hungerford DS, Savory CG, . Use of fibrin sealant to reduce bloody drainage and hemoglobin loss after total knee arthroplasty: a brief note on a randomized prospective trial. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2001;83(10): 1503-5.

- Zhang H, Chen J, Chen F, Que W. The effect of tranexamic acid on blood loss and use of blood products in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012;20(9): 1742-52.