Abstract

Background and purpose Instrumented and non-instrumented methods of fusion have been compared in several studies, but the results are often inconsistent and conflicting. We compared the 2-year results of 3 methods of lumbar fusion when used in degenerative disc disease (DDD), using the Swedish Spine Register (SWESPINE).

Methods All patients registered in SWESPINE for surgical treatment of DDD between January 1, 2000 and October 1, 2007 were eligible for the study. Patients who had completed the 2-year follow-up were included in the analysis. The outcomes of 3 methods of surgical fusion were assessed.

Results Of 1,310 patients enrolled, 115 had undergone uninstrumented fusion, 620 instrumented posterolateral fusion, and 575 instrumented interbody fusion. Irrespective of the surgical procedure, quality of life (QoL) improved and back pain diminished. Change in QoL and functional disability and return to work was similar in the 3 groups. Patients who had undergone uninstrumented fusion had more back pain than the patients with instrumented interbody fusion at the 2-year follow-up (p = 0.02), although the difference was only 7 visual analog scale (VAS) units (95% CI: 1–13) on a 100-point scale. Moreover, 83% of the patients with uninstrumented fusion used analgesics at the end of follow-up as compared to 68% of the patients who had undergone surgery with one of the 2 instrumented fusion techniques.

Interpretation In comparison with instrumented interbody fusion, uninstrumented fusion was associated with higher levels of back pain 2 years after surgery. We found no evidence for differences in QoL between uninstrumented fusion and instrumented interbody fusion.

Several studies have focused on the effects of instrumentation in posterolateral fusion. The results up to 2005 were summarized in a Cochrane Review, which concluded that instrumentation appears to lead to a higher fusion rate, but does not appear to improve quality of life (QoL) or to give reduced pain (Gibson and Waddell Citation2005). Recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have supported that conclusion (Fritzell et al. Citation2002, Ekman et al. Citation2005, Andersen et al. Citation2008). 2 RCTs focused on patients with DDD or post-discectomy syndrome only. In a study by Fritzell et al. (Citation2002), no differences between the 3 methods could be seen. In contrast, a study by Neumann et al. (personal communication) showed superior results of transforaminal interbody fusion (TLIF) over instrumented posterolateral fusion (IPF) for most, but not all, of the outcome measures.

The inconsistencies between the results of these studies may be explained by differences in inclusion criteria and in the number of participants. We therefore compared the results of different fusion methods in routine clinical practice. The Swedish Spine Register (SWESPINE) is well designed for this purpose (Zanoli et al. Citation2006, Strömqvist et al. Citation2009b).

Patients and methods

SWESPINE, the Swedish Spine Register, was started in 1993. More than 80% of all surgical procedures for degenerative lumbar spine disorders in Sweden are included in the register (Strömqvist et al. Citation2005). Preoperative questionnaire data and postal follow-up questionnaires are completed by the patients without any assistance from the surgeon. Preoperative data completed by the patient include age, sex, smoking habits (current use/no use), working conditions, sick listing (partial/full/duration), use of analgesics (regular/occasional), and walking capacity (given as 4 classes). Back and leg pain are reported on a visual analog scale (VAS) and with the Oswestry disability index (ODI). The Short Form-36 health survey (SF-36) and the European Quality of Life questionnaire (EQ-5D) should also be completed. Surgical data, including diagnosis, are recorded by the surgeon without access to the patient’s questionnaires. The current protocol of the register, which has been validated in a test-retest situation, can reliably detect postoperative improvements between large groups of patients such as in a registry (Zanoli et al. Citation2006, Strömqvist et al. Citation2009b).

For this register-based study, the population of interest was all patients who had been operated on for painful DDD using any posterior method for lumbar fusion. Data were obtained for all patients registered in SWESPINE between January 1, 2000 and October 1, 2007. Other conditions, such as central or lateral spinal stenosis, disc herniation, isthmic spondylolisthesis, postoperative instability, and degenerative scoliosis are mutually exclusive diagnoses in the register and they were therefore excluded from the present analysis.

The fusion methods included were uninstrumented fusion (UIF), instrumented posterolateral fusion (IPF), posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF), and transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF). PLIF and TLIF were analyzed as 1 group under the name instrumented interbody fusion (IIF). The reasons for treating the posterior interbody techniques as 1 group were partly the low number of TLIF procedures and partly our suspicion that different modifications of the PLIF procedure had been used in many of the patients described as PLIF in the register. For the UIF procedure, cancellous bone grafting was performed after decortication of posterior bony structures, followed by 3 months of lumbar bracing. Anterior fusion methods were not included in our study because the number of patients was low; in addition, most of the anterior procedures were performed during the early years of SWESPINE. The number of levels treated did not differ statistically significantly between the groups; it ranged from 1 to 5 levels of lumbar fusion.

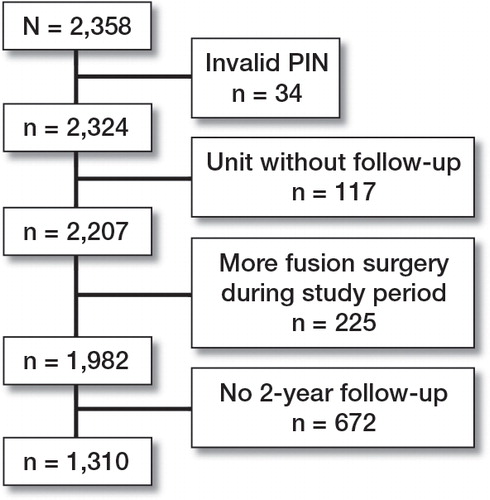

Of the 2,358 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria, an invalid personal identification number was registered in 34 patients, leaving 2,324 patients. In 4 of the 38 hospitals that had reported to the register, the follow-up procedures had failed: none of the 117 patients who had undergone surgery in these hospitals had completed the 2-year follow-up. These patients were therefore excluded. An additional 225 patients had been operated for lumbar fusion more than once during the study period, making it difficult to evaluate the result of one separate procedure. Consequently, these 225 patients were excluded, leaving 1,982 eligible patients (). The distribution of the 3 surgical methods in the 225 patients who were excluded was similar to the distribution of the surgical methods in the patients who had completed the 2-year follow-up (25 patients had undergone UIF, 96 patients IPF, and 104 patients IIF). Of the remaining 1,982 patients, 1,310 (66%) had completed the 2-year follow-up.

VAS for back pain or leg pain at baseline, smoking habits, duration of symptoms, and the distribution of the different fusion methods were similar in the 672 patients who did not complete the 2-year follow-up and in the patients with complete follow-up. Factors that negatively affected the response rate were low age, male sex, previous spine surgery, low EQ-5D at baseline, and high ODI at baseline (data not shown).

Statistics

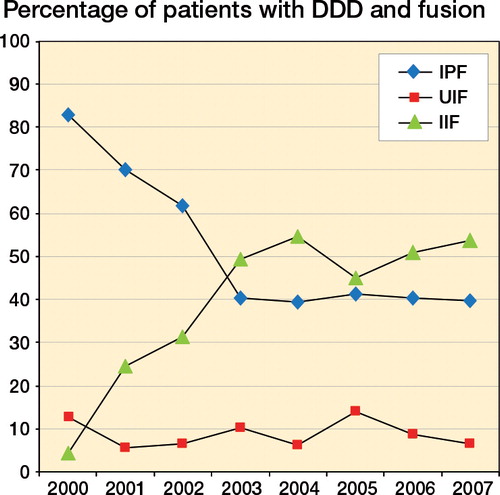

The statistical calculations were performed using SAS software version 9.3. For continuous dependent variables, adjusted means were estimated using PROC MIXED and the Kenward-Roger method. To compensate for possible differences in patient selection and surgical technique between the hospitals, a categorical variable defining each hospital was included as a random-effect parameter in the model to handle within-hospital dependencies. The models were fitted with the assumption of the unstructured covariance matrix, but the Kenward-Roger method approximation involves inflating the estimated variance-covariance matrix of the fixed and random effects. Changes in these variables to the values at the 2-year follow-up and also the model residuals were normally distributed, with Shapiro-Wilk test W value of greater than 0.95. The models were adjusted for age (continuous), sex, smoking, duration of symptoms, previous spine surgery, baseline analgesic use, and also baseline values for the variable under study. Because 2 of the methods studied were unevenly distributed over the study period (), the models were also adjusted for the year of surgery. In many of the hospitals included in the study, 1 surgical method predominated. For dichotomous dependent variables, we used a modified Poisson regression approach with robust error variance (SAS PROC GENMOD) to assess relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (Zhou Citation2004). The multivariable models were adjusted as described above.

The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden (Dnr 2009/164).

Results

Of the 1,310 patients included in the analysis, 115 underwent UIF, 620 IPF, and 575 IIF. The choice of UIF procedure depended on the hospital the patient was operated in. In 1 hospital, 72% of the patients underwent UIF, while this procedure was not performed at all in several other hospitals.

The patients in the IIF group were slightly younger, whereas the proportion of smokers in this group was smaller. The number of patients who had undergone previous spine surgery was lower in the IIF group ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study group, by surgical method

Generic and condition-specific outcome measures

All groups improved from baseline with regard to EQ-5D and ODI (all p < 0.01). The results 2 years after surgery were similar for the 3 fusion methods studied, as measured with the EQ-5D and the ODI ().

Table 2. Outcome 2 years postoperatively related to surgical method. Values are adjusted means (95% CI) a

Back and leg pain

Pain was recorded at the 2-year follow-up using VAS. All groups improved from baseline to follow-up with regard to both back pain and leg pain (all p < 0.01). The patients who had undergone UIF generally had more back pain than the patients with IIF at the 2-year follow-up (p = 0.02), although the difference was only 7 VAS units (CI: 1–13) on the 100-point scale. Leg pain was similar in the 3 groups ().

Use of analgesics and return to work

At the 2-year follow-up, use of analgesics was more frequent in the UIF group (83%) than in the other 2 groups (68% on average: IPF 70% and IIF 65%), corresponding to a multivariable adjusted RR of 1.2 (CI: 1.1–1.3) for those treated with UIF.

The frequency of returning to work was analyzed for those patients who were less than 65 years of age at the time of follow-up, and who had been working before surgery. The RR for returning to work in the UIF group was 0.97 (CI: 0.8–1.2), it was 1.04 (CI: 0.9–1.3) in the IPF group, and it was 0.97 (CI: 0.8–1.2) in the IIF group, indicating no significant differences between the groups.

Discussion

The patients in this study showed significant improvements in back pain, function, and QoL 2 years after surgery when measured with VAS, ODI, and EQ-5D regardless of surgical method (). Due to the large sample size, however, statistical significance could be achieved with small improvements that are not clinically relevant. In the annual report of SWESPINE, the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for VAS after fusion surgery was estimated to be 14 points, and the MCID for EQ-5D was estimated to be 0.2 (Strömqvist et al. Citation2009a, Gatchel et al. Citation2010). For surgical interventions, an MCID of 15 points for ODI has been suggested (Roland and Fairbank Citation2000). In SWESPINE, however, the MCID for ODI after fusion surgery was estimated to be 8 points (Strömqvist et al. Citation2009a). Thus, the patients in our study experienced clinically important improvements in back pain, QoL, and functional disability after surgery.

However, the patients who had undergone UIF reported more back pain 2 years after surgery than the patients treated with an interbody fusion method, but the difference could not be regarded as clinically important. With UIF, there was an indication of an increased probability of use of analgesics compared to IPF and interbody fusion. There were higher levels of back pain after UIF despite a higher consumption of analgesics. Apart from these findings, there were no significant differences evident between the 3 surgical techniques.

The clinically and functionally superior improvement from instrumented fusion as compared to uninstrumented fusion was possibly due to a hypothetically greater rate of fusion. Furthermore, the ability to address the patient’s sagittal balance with instrumentation could improve the long-term results compared to uninstrumented cases. The finding that the postoperative results were similar in all 3 groups could have been biased due to the fact that only a few surgeons were performing many UIFs, thus being highly specialized in this technique, and possibly performing meticulous bone grafting and postoperative bracing. Of course, most surgeons have a preference for one surgical method over the other, whether it is based on evidence or simply on belief. This reasoning is rather hypothetical, but it must be taken into account when evaluating the results of the present study.

The number of patients who were lost to follow-up was a limitation of our study. Of the 1,982 patients included in the study, 1,308 (66%) completed the 2-year follow-up. The patients who were lost to follow-up had a higher frequency of previous spine surgery, had a higher chance of being male, and were somewhat younger than the patients who completed the follow-up. At baseline, the patients who were lost to follow-up generally had an inferior QoL and somewhat higher functional disability. The attendance rate was, however, equal for the 3 surgical methods and the characteristics of the patients who were lost to follow-up were equivalent in the 3 groups. Furthermore, the distribution of the 3 fusion methods was similar in the 225 patients who were excluded because of repeated fusion surgery during the study period. In a recent study from Norway based on a local register for degenerative lumbar surgery, the results from the non-responders were compared with the results from the responders. In that study, 22% of the patients were lost to a 2-year follow-up. These patients were subsequently traced and interviewed by telephone. There were no statistically significant differences in outcome between the responders and the non-responders (Solberg et al. Citation2011). Unfortunately, the nationwide Swedish spine register has a slightly worse degree of loss to follow-up (34%), which might be due to worse register logistics, insufficient discipline of the registering surgeons, or worse patient-reporting morale. However, both our statistical dropout analysis and the results from Norway suggest that the loss to follow-up probably did not affect the external validity of this study.

A further concern with our study is that only 9% of the patients registered received the uninstrumented procedure, which could indicate that this treatment strategy was only used for highly selected patients. However, the baseline data were similar for all 3 treatment groups with regard to most of the variables registered. Furthermore, the choice of UIF procedure depended on the hospital the patient was operated in. To minimize effects of confounding and possible selection bias, outcome values were adjusted for age, sex, smoking, previous spine surgery, duration of symptoms, hospital, and differences at baseline for the variables under study.

Apart from these factors, our analysis included an adjustment for the year of surgery. The reason for this adjustment was partly that we wanted to minimize the influence of any learning factor and partly our assumption that changes in Sweden’s social security system could influence the results. The frequency of sick listing has decreased in Sweden since 2003, probably because the authorities have made a massive effort to promote early return to work. The number of laborers on long-term sick leave in 2008 was less than half of the number in 2002 (Jonsson Citation2009). Because these changes appeared during the study period and because the different fusion methods were not evenly distributed during this period, it was obvious that the analysis of returning to work required adjustment for year of surgery. This adjustment not only influenced return to work but also all of the other variables studied.

The results of fusion surgery in Sweden have improved during the past decade, as measured by EQ-5D or Global Assessment (Strömqvist et al. Citation2009b). This improvement can probably be partly explained by improved surgical techniques and improved selection of patients for the procedure. Moreover, it is known that changes in the compensation system influence registered disability and well-being. This phenomenon was first described in 1879 (Parker Citation1977), and there have been several reports of the influence of compensation systems—not only on return to work, but also on functional disability and QoL in people with low back pain (Haddad Citation1987, Greenough and Fraser Citation1989, Sanderson et al. Citation1995, Carreon et al. Citation2010). The improvement in the results of fusion surgery in Sweden during the past decade could be explained by an improved experienced QoL and function due to a greater level of return to work. These factors should be considered when results of different studies are compared.

We did not analyze the complication rate in this study. We felt that the quality of complication data in SWESPINE is not optimal. In general, more complicated methods lead to higher frequencies of complications, indicating that instrumentation with pedicle screws and interbody fusion techniques generate more complications than posterolateral fusion techniques (Fritzell et al. Citation2003).

Several RCTs on different methods of instrumentation have been performed. In most of these studies, different diagnoses were included (e.g. isthmic spondylolisthesis, degenerative olisthesis, and DDD). In a Danish study a combination of IPF and anterior fusion did not lead to better functional outcome 2 years after surgery compared to IPF alone (Christensen et al. Citation2002). However, at follow-up 5–9 years after surgery in the same patients, IPF combined with anterior fusion showed superior results (Videbaek et al. Citation2006). In two studies comparing IPF with posterior interbody lumbar fusion (PLIF), no differences in clinical outcome could be found (Kim et al. Citation2006, Cheng et al. Citation2009).

The divergent results of randomized studies on different fusion methods can (at least to some degree) probably be explained by patient selection. Inclusion criteria such as “pain emanating from L4-L5 and/or L5-S1” (Fritzell et al. Citation2001), “disabling back and/or leg pain….refractory to at least 6 weeks of conservative treatment” (Kim et al. Citation2006), and exclusion criteria such as “psychosocial instability” (Christensen et al. Citation2002) or “secondary gains from surgical fusion” (Kim et al. Citation2006) are not well defined, and the patient groups in different randomized studies have probably been quite heterogeneous. The inclusion criterion in our study was the diagnosis DDD, as put by the surgeon. This diagnosis is chosen if disk degeneration is evident on MRI-imaging but if no other cause of pain (i.e. central spinal stenosis, foraminal stenosis, or disk herniation) can be identified and manual provocation of the degenerated segment induces pain.

As previously reported (Strömqvist et al. Citation2009b), factors other than the type of surgery (e.g. sex, smoking, duration of symptoms, and previous spine surgery) influence the outcome. We believe that further improvements in the results after fusion surgery are more likely to appear by appropriate selection of patients rather than by the use of increasingly demanding surgical procedures.

YR planned the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. KM performed the statistical analyses and revised the final manuscript. BS contributed to the discussion and revised the final manuscript.

We thank the Register Group of the Swedish Society of Spinal Surgeons for their excellent work with SWESPINE: P. Fritzell, O. Hägg, B. Jönsson, and B. Strömqvist.

No competing interests declared.

- Andersen T, Videbaek TS, Hansen ES, The positive effect of posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion is preserved at long-term follow-up: a RCT with 11-13 year follow-up. Eur Spine J 2008;17(2): 272-80.

- Carreon LY, Glassman SD, Kantamneni NR, Clinical outcomes after posterolateral lumbar fusion in workers’ compensation patients: a case-control study. Spine 2010;35(19): 1812-7.

- Cheng L, Nie L, Zhang L. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion versus posterolateral fusion in spondylolisthesis: a prospective controlled study in the Han nationality. Int Orthop 2009;33(4): 1043-7.

- Christensen FB, Hansen ES, Eiskjaer SP, Circumferential lumbar spinal fusion with Brantigan cage versus posterolateral fusion with titanium Cotrel-Dubousset instrumentation: a prospective, randomized clinical study of 146 patients. Spine 2002;27(23): 2674-83.

- Ekman P, Möller H, Hedlund R. The long-term effect of posterolateral fusion in adult isthmic spondylolisthesis: a randomized controlled study. Spine J 2005;5(1): 36-44.

- Fritzell P, Hägg O, Wessberg P, Nordwall A. 2001 Volvo Award Winner in Clinical Studies: Lumbar fusion versus nonsurgical treatment for chronic low back pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Spine 2001:26 (23): 2521-32.

- Fritzell P, Hägg O, Wessberg P, Nordwall A. Chronic low back pain and fusion: a comparison of three surgical techniques: a prospective multicenter randomized study from the Swedish lumbar spine study group. Spine 2002;27(11): 1131-41.

- Fritzell P, Hägg O, Nordwall A. Complications in lumbar fusion surgery for chronic low back pain: comparison of three surgical techniques used in a prospective randomized study. A report from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Eur Spine J 2003;12(2): 178-89.

- Gatchel RJ, Lurie JD, Mayer TG. Minimal clinically important difference. Spine 2010;35(19): 1739-43.

- Gibson JN, Waddell G. Surgery for degenerative lumbar spondylosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005 (4): CD001352.

- Greenough CG, Fraser RD. The effects of compensation on recovery from low-back injury. Spine 1989; 14(9): 947-55.

- Haddad GH. Analysis of 2932 workers’ compensation back injury cases. The impact on the cost to the system. Spine 1987;12(8): 765-9.

- Jonsson MS. Report on sick-leave 4th quarter 2008. Swedish Confederation of Enterprise: Stockholm 2009.

- Kim KT, Lee SH, Lee YH, Clinical outcomes of 3 fusion methods through the posterior approach in the lumbar spine. Spine 2006;31(12): 1351-7.

- Parker N. Accident litigants with neurotic symptoms. Med J Aust 1977;2(10): 318-22.

- Roland M, Fairbank J. The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. Spine 2000;25(24): 3115-24.

- Sanderson PL, Todd BD, Holt GR, Getty CJ. Compensation, work status, and disability in low back pain patients. Spine 1995;20(5): 554-6.

- Solberg TK, Sørlie A, Sjaavik K, Would loss to follow-up bias the outcome evaluation of patients operated for degenerative disorders of the lumbar spine?. Acta Orthop 2011;82(1): 56-63.

- Strömqvist B, Fritzell P, Hägg O, Jönsson B. One-year report from the Swedish National Spine Register. Swedish Society of Spinal Surgeons. Acta Orthop (Suppl 319) 2005;76:1-24

- Strömqvist B, Fritzell P, Hägg O, Primaryoutcome measure. In:SWESPINE – the Swedish Spine Register. The 2009 report. Swedish Society of Spine Surgeons; 2009a: 45-7.

- Strömqvist B, Fritzell P, Hägg O, Jönsson B. The Swedish Spine Register: development, design and utility. Eur Spine J (Suppl 3) 2009b;18:294-304

- Videbaek TS, Christensen FB, Soegaard R, Bünger CE.Circumferential fusion improves outcome in comparison with instrumented posterolateral fusion: long-term results of a randomized clinical trial. Spine 2006;31(25): 2875-80.

- Zanoli G, Nilsson LT, Stromqvist B. Reliability of the prospective data collection protocol of the Swedish Spine Register: test-retest analysis of 119 patients. Acta Orthop 2006;77(4): 662-9.

- Zhou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159(7): 702-6.