Abstract

Background and purpose Bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs) can be used in non-unions to replace autograft. BMPs induce osteoblasts and (less well known) also osteoclasts, which can in turn be controlled by a bisphosphonate. In the present study, our aim was to improve the biological effect of autologous bone graft by adding an anabolic BMP, with or without bisphosphonates, in an open-fracture model prone to non-union.

Methods Rat femurs were osteotomized and fixed with an intramedullary K-wire. Autograft was placed at the osteotomy, mixed with either saline or BMP-7. After 2 weeks, the rats had a single injection of saline or of a bisphosphonate (zoledronate). The rats were killed after 6 weeks and the femurs were evaluated by radiography, micro-CT, histology, and 3-point bending test.

Results All fractures healed. The callus volume was doubled in the BMP-treated femurs (p < 0.01) and increased almost 4-fold in the femurs treated with both BMP and systemic zoledronate (p < 0.01) compared to autograft. In mechanical testing, the autograft group reached approximately half the strength of the contralateral, non-osteotomized femur (p < 0.001). By adding BMP to the autograft, the strength was doubled (p < 0.001) and with both BMP and systemic zoledronate, the strength was increased 4-fold (p < 0.001) compared to autograft alone.

Interpretation The combination of BMP and bisphosphonate as an adjunct to autograft is superior to autograft alone or combined with BMP. The combination may prove valuable in the treatment of non-unions.

Several factors are known to increase the risk of developing a delayed union or non-union. General factors include malnutrition, infection, smoking, diabetes, and the use of drugs, e.g. NSAIDs, which can all lead to decreased bone formation and a hypotrophic/atrophic non-union. Also, local factors such as a devascularized periosteum in open fractures or after extensive surgical approaches might lead to hypotrophic/atrophic non-union (Calori et al. Citation2007, Perumal and Roberts Citation2007). Autograft is the gold standard for induction of callus formation in established hypotrophic/atrophic non-unions. Instead of autograft, recombinant bone morphogenic protein (BMP), which is commercially available as rhBMP-2 and -7, can be used alone or as an adjunct to either allograft or autograft to induce osteoblast recruitment and differentiation (Little et al. Citation2007). In randomized trials, BMP has been shown to be equivalent but not better than autograft regarding rate of healing (Jones et al. Citation2006, Ristniemi et al. Citation2007, Kanakaris et al. Citation2008). What is less well known is that BMPs also stimulate cells of the osteoclastic cell lineage, inducing bone resorption (Giannoudis et al. Citation2007). Bisphosphonates are a group of drugs that inactivate osteoclasts by inducing apoptosis (Rogers et al. Citation2011), thereby inhibiting bone resorption.

In previous rat bone chamber studies using cancellous bone graft, the speed of remodeling and the volume of remodeled graft were found to be increased by BMP, but most of the newly formed bone was resorbed. By adding a bisphosphonate, locally (Belfrage et al. Citation2011) or systemically (Harding et al. Citation2008), the anabolic effect of the BMP was retained while the resorption was inhibited. The amount of remaining new-formed bone after remodeling increased several fold. The combination of BMP and bisphosphonates has also been used in a critical defect model (Little et al. Citation2005) and an open-fracture model (Doi et al. Citation2011), with similar results.

We investigated whether BMP or BMP together with a systemic bisphosphonate can augment autograft in an osteotomy model designed to reflect the healing difficulties in open fractures. We hypothesized that by adding a bisphosphonate, the resorptive effect of BMP would be muted and the osteoinductive effect would be retained—and that this would result in stronger calluses.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 36, 309–356 g; Möllegaard, Copenhagen, Denmark) were housed 2 and 2 in pairs with free access to food and water. They were allowed unrestricted weight bearing. The study was approved by the local animal ethics committee at Lund University.

Surgery

The rats were anesthetized using pentobarbital sodium (15 mg/mL), diazepam (2.5 mg/mL), and saline administered intraperitoneally. Preoperatively, Streptocillin was given as infection prophylaxis. Subcutaneous buprenorphin was given immediately postoperatively and paracetamol/acetaminophen was given over the following days for pain relief. Prior to surgery, the extremities were shaved and prepared in a sterile fashion. In each rat, both legs were operated. The proximal tibia on the right side was used for harvesting of the autologous bone graft, and the left femur was used for the osteotomy. The bone graft was harvested through an anteromedial incision. A hole was made in the cortex using a 2.7-mm drill bit and bone graft was harvested immediately distal to the physis. The left femur was approached through a lateral skin incision and the plane between the biceps femoris muscle and the gluteus superficialis muscle was identified. The muscle and periosteum were stripped circumferentially at the mid-diaphyseal level and the bone was transversely osteotomized using an oscillating power saw. The bone ends were then fixed in apposition with a single intramedullary K-wire. Depending on randomization, autologous bone graft, with or without BMP, was placed around the osteotomy and the wound was closed in layers. The animals were killed after 6 weeks.

Drug treatment

The rats were randomized to 3 groups: (1) group A, autograft, (2) group B, autograft + BMP, and (3) group C, autograft + BMP + systemic zoledronate injection after 2 weeks. A BMP-7 putty was prepared by mixing Osigraft (Stryker) powder (2 mg of OP-1 in 570 mg collagen) with 130 mg of sterile carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) and sterile water. The mixture was divided into equal doses, resulting in a dose of 50 µg BMP-7 to be administered to each of the animals in groups B and C. For groups B and C, the bone graft was mixed with the BMP putty and then applied circumferentially at the site of the pinned osteotomy. The animals in group C received a single subcutaneous injection of zoledronate (0.1 mg/kg) 2 weeks after surgery (Amanat et al. Citation2007).

Outcome

The rats were killed 6 weeks after surgery by an injection of pentobarbital sodium intraperitoneally, and both femurs were harvested and stored in saline-soaked gauzes at –20˚C. AP radiographs were taken and the K-wires were extracted.

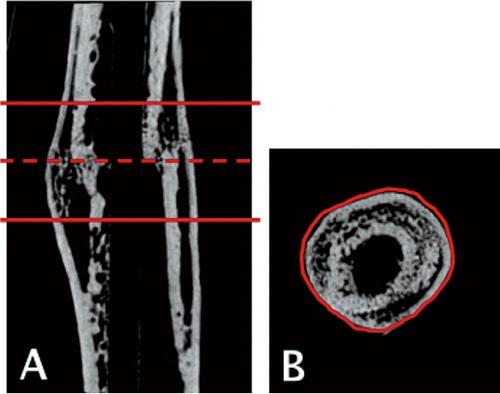

Micro-computed tomography

The femurs were scanned using an isotropic voxel size of 19 µm (SkyScan 1172, v. 1.5; SkyScan, Aarteselar, Belgium) using energy settings of 50 kV and 200 µA, a 0.5-mm aluminum filter, and 8 repeated scans. Image reconstruction was performed (SkyScan NRecon package v. 1.5.1.4) by correcting for ring artifacts and beam hardening (20%). Following reconstruction, the individual fracture lines were identified by simultaneously viewing multiple orthogonal slices (Skyscan DataViewer v. 1.4). The region of interest for each bone was determined as being approximately 3 mm proximal and distal to the fracture line (150 images) (Nyman et al. Citation2009). Within that region of interest (ROI), semi-automatic segmentation was used on each 2D image to identify the circumferential boundaries of the calluses () (Matlab v. 7.6.0; Mathworks Inc.; SkyScan CTAn v. 1.9.1.0). Calibration of bone mineral density (BMD) was carried out according to the system manufacturer’s protocol. A water phantom and 2 hydroxyapatite phantoms of known density (0.25 and 0.75 g/cm3) were scanned. To distinguish fully mineralized tissue from poorly mineralized tissue and soft tissue, 2 thresholds were used. Fully mineralized tissue was assumed to have a BMD of more than 0.642 g/cm3 (Morgan et al. Citation2009), resulting in grayscale values of 98–255. Poorly mineralized tissue was assumed to have a BMD value of between 0.410 and 0.642 g/cm3 (Isaksson et al. Citation2009), resulting in grayscale values of 68–97. The threshold values were chosen based on visual inspection of the images, qualitative comparison with histological sections, and previous studies. The following parameters were calculated from the callus region of interest for each specimen: total callus volume (TVc), fully mineralized bone volume (BVhigh), poorly mineralized tissue volume (BVlow), bone volume fraction (BVhigh / TVc), and average tissue mineral density (TMD). TMD was calculated by using only the voxels that exceeded the threshold for fully mineralized bone.

Figure 1. The region of interest (ROI) for each bone was determined by first identifying the fracture line (dashed line) and then defining a region approximately 3 mm (150 images) proximal and distal to the fracture line (solid lines) (panel A). Within the defined ROI, semi-automatic segmentation was used on each 2D image to identify the circumferential boundaries of the calluses (panel B).

Mechanical testing

The osteotomized femur from each specimen and the corresponding intact contralateral femur that were used as internal control were tested in 3-point-bending until failure (8511 load frame; Instron, High Wycombe, UK; with a TestStar II controller; MTS, Minneapolis, MN). A custom-made test rig with 3-mm solid brass bars was used. The distance between the supports was 16 mm. The first support was placed immediately distal to the lesser trochanter and the second was placed just proximal to the femoral condyles.

The femurs were mounted for testing in the AP plane with the posterior surface of the bone resting on the 2 lower supports. The bones were preloaded to 10 N at a speed of 0.1 mm/sec and allowed to adapt for 10 seconds. Thereafter, the bone was tested until failure with a constant speed of 1.0 mm/sec. Time, force, and displacement were recorded. Based on a force-displacement curve, the ultimate force for each of the bones was determined and the stiffness and energy absorbed were calculated.

Histology

After the mechanical testing, the osteotomized femurs were prepared for histology. The bones were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 24 h, decalcified in 10% EDTA for 2.5 weeks, and dehydrated in alcohol before being embedded in paraffin. A microtome with a cool cut and section transfer system was used to cut centerpiece sections with 5-µm thickness. The sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin using a standard protocol.

Statistics

The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis post hoc test was used to compare each parameter from micro-CT and mechanical testing from the 3 treatment groups, and between groups. Non-parametric paired test (Wilcoxon signed-rank test) was used to compare the mechanical test data from the osteotomized femurs and the contralateral control femurs.

Results

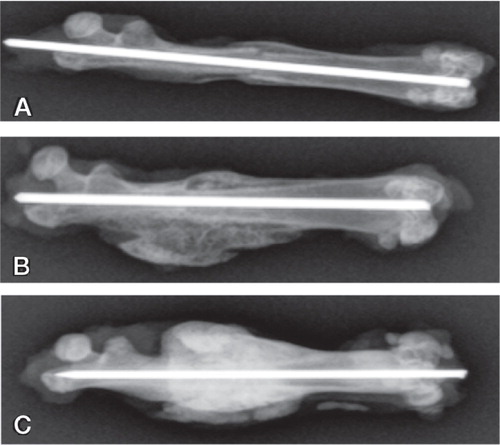

Radiography

Radiographs taken after bone harvest were evaluated for healing in blind fashion. In group A (autograft), all bones were judged as healed with bridging calluses, but the fracture line was still visible in 4 of 12 femurs (). The bones in the 2 other groups were healed with larger calluses compared to group A, and without visible fracture lines. The calluses in group C (autograft + BMP + zoledronate) appeared larger and denser than the calluses in all other groups.

Figure 2. Radiographs of the median samples from each group (based on callus volume) after harvest at 6 weeks.

A. Group A (autograft group) with fracture line still visible.

B. Group B (autograft + BMP) showing larger calluses than in group A.

C. Group C (autograft + BMP + zoledronate) showing an even larger callus and a denser appearance, reflecting increased BMD.

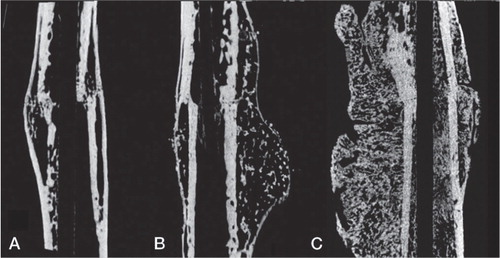

Micro-computed tomography

Differences between the groups were observed both qualitatively () and quantitatively (). The total callus volume (TVc) was significantly greater in the 2 BMP-treated groups (B and C) than in the rats that received autograft alone (group A) (p < 0.001). Also, the TVc was significantly greater in group C (autograft + BMP + zoledronate) than in group B (autograft + BMP) (p < 0.01).

Figure 3. Micro-CT rendered image of median samples from each group (based on callus volume). A. Autograft. B. Autograft + BMP. (C) Autograft + BMP + zoledronate.

Table 1. Bone callus measurements based on microCT. Total callus volume (TVc), highly and lowly mineralized bone volume (BVhigh, BVlow), bone volume fraction (BVhigh / TVc) and tissue mineral density (TMD) were calculated. Mean and standard deviation (SD) are given, as well as statistical significant differences based on Kruskal-Wallis post hoc test (a p<0.05, b p<0.01, c p<0.001 compared to group A; d p<0.01 compared to group B). ABG stands for saline treated bone graft

Both the high and low mineralized bone volume (BVhigh and BVlow) were significantly higher (p < 0.01) in the 2 groups that received BMP than in the group that received autograft alone (group A) (). Group C (autograft + BMP + zoledronate) had BVhigh and BVlow values that were even higher than in group B (autograft + BMP) (p < 0.01). Compared to saline-treated autograft (group A), the bone volume fraction (BVhigh / TVc) was significantly lower in group B (autograft + BMP) (p < 0.01). In group C (autograft + BMP + zoledronate), the bone volume fraction was equivalent to that in group A. Thus, the treatment combination used in group B (autograft + BMP) led to increased callus volume and absolute bone volume but to reduced bone volume fraction, whereas the treatment combination used in group C (autograft + BMP + zoledronate) led to both increased callus volume and increased absolute bone volume fraction compared to the autograft group. The average TMD in the callus decreased in the 2 BMP-treated groups compared to the autograft group.

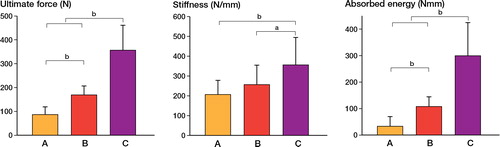

Mechanical testing

The MEAN ultimate force-to-fracture of the non-osteotomized femurs, used as controls, ranged from 158 N to 164 N in the three groups (). The osteotomized femurs in group A fractured at approximately half that force (p < 0.001). When BMP was added as a local adjunct to the autograft (group B), the strength doubled compared to the autograft-treated bones in group A, and then equaled that of the non-osteotomized contralateral femurs. When bisphosphonate was given systemically in addition to the locally-applied BMP (group C), the ultimate force doubled compared to that for the control femurs () (p < 0.001). The bending stiffness decreased significantly in groups A and B compared to that in control femurs (p < 0.01) (), whereas the stiffness in group C was comparable to that in the controls. The absorbed energy of the bones treated with autograft in isolation (group A) was less than half of that of the control femurs (). The bones in group B were equivalent to the controls in this respect, and the bones in group C were able to absorb more than 3 times the energy before failure compared to the controls.

Table 2. Mechanical testing outcome for experimental (osteotomized) and the control (contralateral non-fractured) femurs. Based on three-point bending, the ultimate force, stiffness and absorbed energy were calculated. The percentage differences (Diff.) and the statistical differences between the experimental and control side (Wilcoxon signed rank test) are given

When comparing the treatment combinations in the osteotomized femurs with each other, group C (autograft + BMP + zoledronate) showed higher ultimate force (p < 0.001), bending stiffness (p < 0.05), and absorbed energy (p < 0.001) than all other treatment combinations ().

Figure 4. Mechanical testing data from the experimental (osteotomized) femurs in Group A, B, and C (see Figure 2). Mean and standard deviation (SD) are given for ultimate force (left panel), bending stiffness (middle panel), and absorbed energy (right panel). Statistically significant differences, based on Kruskal-Wallis post hoc test, are indicated ( a p < 0.05, b p < 0.001).

Discussion

Great expectations have been invested in the use of the commercially available anabolic drugs PTH and BMP. Both have been successful in closed-fracture healing studies in animals, increasing the strength of a forming callus (Hak et al. Citation2006, Nozaka et al. Citation2008). In the present study, we investigated ways to improve the biological function of BMP by adding an autograft, the gold standard in non-unions today. We used a challenging open-fracture model where the periosteum was removed from the fracture ends to mimic the conditions of an open devascularized fracture with an increased risk of delayed union or non-union. Untreated, only about 60% of such osteotomies heal (Tägil et al. Citation2010).

Previously, only BMP (but not PTH or bisphosphonates) has been shown to increase the healing rate (Tägil et al. Citation2010, Doi et al. Citation2011). The present experiment was therefore designed without an “autograft + bisphosphonate” group simply because fracture healing was not expected to occur. Autograft alone has never been tested in this model; we found that autograft alone made all fractures heal. Combining autograft with BMP doubled the strength of the healing callus compared to autograft alone. In micro-CT analysis, BMP caused a decrease in the bone volume fraction of the callus, possibly due to activation of the osteoclasts and premature remodeling before fracture healing. By treating the animal with a single injection of bisphosphonate, we prevented this premature resorption during early callus formation. A further doubling of the strength was reached in the mechanical test with a combination of BMP and bisphosphonate, and the calluses were 4 times as strong as with autograft alone.

Our experiment was designed with bisphosphonate as an adjunct to BMP. We know from the previous studies (Tägil et al. Citation2010, Amanat et al. Citation2007) that both PTH and bisphosphonates increased the strength of the 60% of fractures that did heal, and it is also plausible that with the present model, using autograft, increased strength might be achieved with both of these drugs. Future studies are needed to establish this. When combining an autologous bone graft with BMP and bisphosphonate, one would expect the callus to be larger and denser but also possibly less remodeled. A more immature callus might conceivably be inferior in strength because of a biomechanically suboptimal random orientation of the trabeculas. We could not show that. In contrast, even a less organized callus, as indicated by an inferior trabecular orientation in the micro-CT analysis, was stronger, compensated for by the increased callus size. Both treatment with autograft alone and treatment with autograft combined with BMP resulted in weaker calluses than the combination of autograft, BMP, and bisphosphonate.

When bisphosphonate is given systemically as an injection 2 weeks postoperatively, a large proportion of the bisphosphonate administered is distributed to the fracture site. The optimal timing for systemic bisphosphonate administration is not fully known, but since bisphosphonates only bind to bone present at the time of administration, a delayed dosing has been suggested. Single injections after 1 or 2 weeks have been shown to be superior to injections at the time of fracture (Amanat et al. Citation2007). Once chemically bound to the bone in the fracture gap, bisphosphonates remain for a long time until resorbed. It has been shown that bisphosphonate causes delayed—but not aborted—remodeling, and in time the calluses will remodel (McDonald et al. Citation2008).

Both BMP and bisphosphonates are drugs that are approved for human use, and the combination could be the subject of a pilot clinical series. In future studies, drugs that are more short-acting in their delay of the osteoclastic response, such as osteoprotegerin or denosumab, could be used to limit the reduced remodeling to occur only during the immediate post-fracture healing period.

All the authors participated in the conception and design of the study, and in writing and approval of the manuscript. In addition, PB and MT carried out the animal experiment, PB the mechanical testing, and HI the micro-CT analysis and the statistics.

The project was supported by the Swedish Research Council (project 2031), the Greta and Johan Kock Foundation, the Alfred Österlund Foundation, the Maggie Stephens Foundation, the Thure Carlsson Foundation, Vinnova, and the Medical Faculty of Lund University. BMP-7 (Osigraft) was a gift from Stryker Biotech, Malmö, Sweden and the zoledronate (Zometa) was a gift from Novartis, North Ryde, NSW, Australia.

- Amanat N, McDonald M, Godfrey C, Bilston L, Little D. Optimal timing of a single dose of zoledronic acid to increase strength in rat fracture repair. J Bone Miner Res 2007; 22 (6): 867-76.

- Belfrage O, Flivik G, Sundberg M, Kesteris U, Tägil M. Local treatment of cancellous bone grafts with BMP-7 and zoledronate increases both the bone formation rate and bone density. A bone chamber study in rats. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (2): 228-33.

- Calori GM, Albisetti W, Agus A, Iori S, Tagliabue L. Risk factors contributing to fracture non-unions. Injury. 2007 38 Suppl 2:S11-8. Erratum in: Injury 2007; 38 (10): 1224.

- Doi Y, Miyazaki M, Yoshiiwa T, Hara K, Kataoka M, Tsumura H. Manipulation of the anabolic and catabolic responses with BMP-2 and zoledronic acid in a rat femoral fracture model. Bone 2011; 49 (4): 777-82.

- Giannoudis PV, Kanakaris NK, Einhorn TA. Interaction of bone morphogenetic proteins with cells of the osteoclast lineage: review of the existing evidence. Osteoporos Int 2007; 18 (12): 1565-81.

- Hak DJ, Makino T, Niikura T, Hazelwood SJ, Curtiss S, Reddi AH. Recombinant human BMP-7 effectively prevents non-union in both young and old rats. J Orthop Res 2006; 24: 11-20.

- Harding AK, Aspenberg P, Kataoka M, Bylski D, Tägil M. Manipulating the anabolic and catabolic response in bone graft remodeling: Synergism by a combination of local BMP-7 and a single systemic dosis of zoledronate. J Orthop Res 2008; 26 (9): 1245-9.

- Isaksson H, Grongroft I, Wilson W, van Donkelaar CC, van Rietbergen B, Tami A, Huiskes R, Ito K. Remodeling of fracture callus in mice is consistent with mechanical loading and bone remodeling theory. J Orthop Res 2009; 27: 664-72.

- Jones AL, Bucholz RW, Bosse MJ . Recombinant human BMP-2 and allograft compared with autogenous bone graft for reconstruction of diaphyseal tibial fractures with cortical defects. A randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006; 88: 1431-41.

- Kanakaris NK, Calori GM, Verdonk R . Application of BMP-7 to tibial non unions: a 3-year multicenter experience. Injury 2008; 39: 83-90.

- Little DG, McDonald M, Bransford R, Godfrey CB, Amanat N. Manipulation of the anabolic and catabolic responses with OP-1 and zoledronic acid in a rat critical defect model. J Bone Miner Res 2005; 20 (11): 2044-52.

- Little DG, Ramachandran M, Schindeler A. The anabolic and catabolic responses in bone repair. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2007; 89 (4): 425-33.

- McDonald MM, Dulai S, Godfrey C, Amanat N, Sztynda T, Little DG. Bolus or weekly zoledronic acid administration does not delay endochondral fracture repair but weekly dosing enhances delays in hard callus remodeling. Bone 2008; 43 (4): 653-62.

- Morgan EF, Mason ZD, Chien KB, Pfeiffer AJ, Barnes GL, Einhorn TA, Gerstenfeld LC. Micro-computed tomography assessment of fracture healing: relationships among callus structure, composition, and mechanical function. Bone 2009; 44: 335-44.

- Nozaka K, Miyakoshi N, Kasukawa Y, Maekawa S, Noguchi H, Shimada Y. Intermittent administration of human parathyroid hormone enhances bone formation and union at the site of cancellous bone osteotomy in normal and ovariectomised rats. Bone 2008; 42: 90-7.

- Nyman J, Munoz S, Jadhav S. Quantitative measures of femoral fracture repair in rats derived by micro-computed tomography. J Biomech 2009;42: 891-8.

- Perumal V, Roberts CS. Factors contributing to non union of fractures. Curr Orthop 2007; 21: 258-61.

- Ristniemi J, Flinkkilä T, Hyvönen P, Lakovaara M, Pakarinen H, Jalovaara P. RhBMP-7 accelerates the healing in distal tibial fractures treated by external fixation. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2007; 89: 265-72.

- Rogers MJ, Crockett JC, Coxon FP, Mönkkonen J. Biochemical and molecular mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates. Bone 2011; 49 (1): 34-41.

- Tägil M, McDonald MM, Morse A, Peacock L, Mikulec K, Amanat N, Godfrey C, Little DG. Intermittent PTH (1-34) does not increase union rates in open rat femoral fractures and exhibits attenuated anabolic effects compared to closed fractures. Bone 2010; 46 (3): 852-9