Abstract

Background and purpose Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) remains a devastating complication of arthroplasty. Today, most displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly are treated with arthroplasty. We estimated the incidence of and risk factors for PJI in primary arthroplasty after femoral neck fracture.

Patients and methods Patients admitted for a femoral neck fracture in 2008 and 2009 were registered prospectively. We studied clinical, operative, and infection data in 184 consecutive patients.

Results 9% of the patients developed a PJI. Coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus aureus were the most frequently isolated organisms. We found that preoperative waiting time was associated with PJI and also with urinary tract infection. The median preoperative waiting time was 37 (11–136) h in the infection group as opposed to 26 (4–133) h in the group with no infection (p = 0.04). The difference remained statistically significant after adjusted analysis. The success of treatment with debridement and retention of the prosthesis was limited, and 5 of the 17 patients with PJI ended up with a resection arthroplasty. The 1-year mortality rate was 21% in the patients with no infection, and it was 47% in the infection group (p = 0.03).

Interpretation We found a high incidence of PJI in this elderly population treated with arthroplasty after hip fracture, with possibly devastating outcome. The length of stay preoperatively increased the risk of developing PJI.

Most displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly are treated with hemiarthroplasty (Bhandari et al. Citation2005). Several authors have reported better functional outcome and fewer reoperations with hemiarthroplasty rather than osteosynthesis (Rogmark et al. Citation2002, Parker and Gurusamy Citation2006, Frihagen et al. Citation2007). Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) remains a devastating complication of arthroplasty. An increasing incidence of revision due to infection has been reported during the past decade (Kurtz et al. Citation2008, Dale et al. Citation2009). While the infection rate after primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) is around 1% (Phillips et al. Citation2006, Kurtz et al. Citation2008), it is higher in hemiarthroplasty after femoral neck fracture (0–18%) (Bhandari et al. Citation2003, Ridgeway et al. Citation2005). The consequences of a PJI in elderly patients, often with substantial comorbidities, are loss of function and increased morbidity and mortality. Cost of treatment has been reported to increase substantially following early infection after hip fracture surgery (Edwards et al. Citation2008). Although PJI is one of the most frequent complications after hemiarthroplasty (Rogmark et al. Citation2002, Ridgeway et al. Citation2005), little has been published on infections in elderly patients with a fracture of the femoral neck.

In this retrospective study, we evaluated the incidence of and risk factors for PJI in patients with displaced femoral neck fractures treated with arthroplasty. Bacteriology, outcome, and mortality were also studied.

Patients and methods

Patients who were admitted for a hip fracture were prospectively registered in the hospital fracture registry. A chart review of all patients with femoral neck fracture who were treated with arthroplasty between January 2008 and December 2009 was conducted retrospectively median 18 (12–33) months after surgery. Re-admissions, outpatient visits, and mortality were registered through the electronic chart system, which is linked to the National Population Registry. Patients from outside the hospital catchment area were excluded, to minimize the risk of missing any infections that were treated elsewhere. Patients with pathological fractures were also excluded. This left 184 patients for inclusion. No bilateral procedures were registered. The study was approved by the hospital’s Data Protection Official for Research.

Most patients (177, 96%) were operated on with a bipolar cemented hemiarthroplasty using gentamicin cement (Charnley stem (176 cases) and Elite plus stem (1 case); DePuy International Ltd., Leeds, UK). An uncemented stem was implanted in 4 patients (Corail; DePuy International Ltd, Leeds, UK). All patients received a 28-mm cobalt-chromium head and the same bipolar cup (Mobile cup; DePuy). A cemented THA using gentamicin cement and 28-mm cobalt-chromium head was used in 3 patients (Charnley stem and Marathon cup; both DePuy). All patients were operated on by the orthopedic surgeons on call—all of whom were experienced residents—except for the 3 patients treated with THA, who were operated on by consultants specialized in joint replacement.

Surgery was performed in a standard operating room with laminar air flow. The patients were placed in a lateral position and the lateral approach was used. All received prophylactic systemic antibiotics at induction, aiming at 10–15 min before incision, and 3 additional doses within 24 h postoperatively. Cephalotin (2 g) was given unless the patient had known penicillin allergy, in which case clindamycin (600 mg) in 3 doses was given. Medical condition was assessed by ASA score. We registered the following patient-dependent variables as potential risk factors for postoperative infection: age, sex, obesity (BMI > 30), previous PJI in other hip, diabetes, chronic renal insufficiency or urinary tract infections, coexisting malignancy, chronic lower leg ulcer, and use of steroids or other immunosuppressive medication. We also registered treatment-dependent variables: time from injury and admission to surgery, length of surgery, and the time of day at which the surgery was performed ().

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of patients according to infection

PJI was classified as early when symptoms presented less than 4 weeks after arthroplasty, otherwise as late according to Tsukayama et al. (Citation1996). Infection was clinically diagnosed, based on the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) definition of deep incisional surgical site infection (Mangram et al. Citation1999). In cases with reoperation for PJI, several tissue samples were obtained perioperatively for culture. A minimum of 2 biopsies had to be positive to regard the joint as infected. Superficial wound swabs (Stewart’s medium) were used for the bacteriological diagnosis in patients treated without revision surgery.

When soft tissue revision was performed, the surgical strategy was excision of the wound margins, removal of all debris and necrotic soft tissue, and then pulsatile lavage with 9 L saline. The modular head and bipolar cup were changed. 1 or 2 gentamicin-containing mats were put into the joint and beneath the fascia before closure. An empirical intravenous antimicrobial regimen containing cloxacillin and vancomycin was given until definitive microbiological results were known.

Statistics

The chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare categorical variables. Mann-Whitney U-test was used for comparison of patient groups. Logistic regression analysis was used for adjusted analysis of infection risk. Cox regression analysis with constant time at risk gave similar results (data not shown). Any p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. We used SPSS for Windows version 18.0.

Results

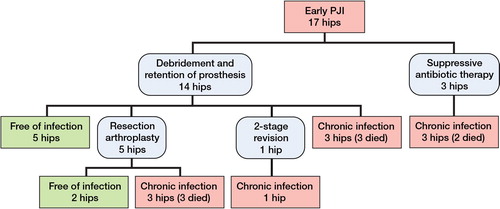

17 (9%) of the 184 eligible patients developed a PJI within 4 weeks after arthroplasty. 3 were not reoperated due to comorbidities. The remainder were reoperated at least once (Figure). No late infections were identified.

Risk factors

6 of the 58 men (10%) developed a PJI, as compared to 11 of the 126 women (9%) (p = 0.7). Mean (SD) age in the infection group was 79 (9) years and it was 81 (10) years in the uninfected group (p = 0.4). There was an increased risk of PJI for all risk factors registered, but most differences in risk were not statistically significant except for BMI over 30 (p = 0.04) (). There was, however, a statistically significant difference between the patients who had 1 risk factor and those without, and also when comparing patients with 2 or more risk factors with patients who had 1 or no known risk factor(s) ().

Table 2. The risk of postoperative infection in patients with or without known risk factors

There was a statistically significantly longer preoperative waiting time in the infection group than in the group without infection. The median time from admission to surgery was 37 (11–136) h in the infected group and 26 (4–133) h in the uninfected group (p = 0.04). We found a higher infection rate, but not statistically significantly so, with a relative risk of about 2 (95% CI: 0.7–5; p = 0.2) for preoperative waiting up to 48 h. At 72 h, the relative risk of infection was 4 (CI: 1.4–10; p = 0.01) and for those who waited more than 96 h, the relative risk was 4 (CI: 1–13.5; p = 0.04) (). All patients were operated between 9 a.m. and 1 a.m., evenly distributed during the day. 10 of 93 (11%) who were operated between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. and 6 of 89 (7%) who were operated between 6 p.m. and 1 a.m. later developed an infection (p = 0.3, with data missing for 2 patients).

Table 3. Relation between risk of prosthetic joint infection and time between admission and surgery

Mean (SD) time of surgery was similar in both groups: 77 (20) min in the group without infection (n = 145) and 78 (13) min in the infection group (n = 16). Data on duration of surgery were missing for 23 patients. The preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis was given at median 18 (5–30) min before incision in the group with infection. There were no statistically significant correlations between time from admission to surgery on the one hand and ASA group, any comorbidity, age, or sex on the other.

In a logistic regression analysis with postoperative infection as the dependent variable and age, sex, ASA group, the individual risk factors in , and cognitive failure as covariates, time from admission to surgery remained a significant predictor of infection (odds ratio (OR) = 1.0 per hour, CI: 1.0–1.1; p = 0.02)). Urinary tract infection was also significant, with an OR of 10 (CI: 1.3–72; p = 0.04). The use of steroids and other immunosuppressive medications was borderline-significant (OR = 6, CI: 0.9–42; p = 0.07). The other assumed risk factors were not statistically significant, including a BMI of > 30, which was statistically significant in the unadjusted analysis

Microbiology

The PJIs were culture-positive in 14 of the 16 patients from whom samples were obtained. In 1 patient who was treated with suppressive antibiotics, no bacteriology was performed. The most frequently isolated organisms were coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) and Staphylococcus aureus, either alone or as a polymicrobial infection (). No methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was found.

Table 4. Results of culture in 17 hips with PJI

Treatment

14 patients were treated with soft tissue debridement and retention of the prosthesis at median 15 (9–41) days after arthroplasty (Figure). The median number of soft tissue revisions was 1 (1–3). 3 patients were treated with lifelong suppressive antibiotic therapy and 1 patient was not treated with antibiotics at all. In the remaining 13 patients, the median duration of antimicrobial therapy was 48 (12–90) days. The mortality at 30 days was 11/184 (6%) and at 1 year it was 43/184 (23%). When looking at the 2 groups separately, the 1-year mortality rate in patients with infection was 8/17 and in the group without infection it was 35/167 (21%) (p = 0.03). In a logistic regression analysis with mortality as the dependent variable, higher age (OR = 1.2; p < 0.001), diabetes (OR = 7; p = 0.01), and previous malignant disease (OR = 53; p = 0.01) were independent risk factors for 1-year mortality. PJI was borderline-significant (OR = 5; p = 0.07). Preoperative delay was not associated with mortality. Details of the clinical data and treatment in the 17 patients with PJI are presented in Table 5 (see Supplementary data).

Discussion

We found an infection rate of 9%. As expected, this was much higher than for primary THA. In this elderly and more frail patient group, both the trauma and the surgery may have contributed to immune dysfunction, which may predispose to septic complications. The infection rate in our study seems to be comparable to that in a recent publication from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, which reported a 1-year incidence of surgical site infections after hemiarthroplasty of 7.3% (Dale et al. Citation2011). In another previous Norwegian publication on hemiarthroplasty after displaced femoral neck fractures, an infection rate of 7% was reported (Frihagen et al. Citation2007). However, other previous reports on hemiarthroplasty after femoral neck fractures have found infection rates of only 1–2% (Partanen et al. Citation2006, Edwards et al. Citation2008, Figved et al. Citation2009). It is difficult to explain the discrepancy between our results and the low infection rates in the latter publications. The patients in our study were operated in laminar-flow operating theaters, they were treated with appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis, and gentamicin-impregnated cement was used. The study was limited to 2 years, with relatively few patients. As PJI does not occur evenly over time, we may have collected data from a period with clusters of infections. The rates of PJI reported after primary hemiarthroplasties have varied from 0% to 18% (Bhandari et al. Citation2003). This may have been due to different hospital settings, sample sizes, and definitions of PJI (Ridgeway et al. Citation2005). The classification of infections into late and early, periprosthetic/deep surgical site infection (SSI), and superficial SSI complicates comparisons between studies.

Risk of infection

The previously reported risk factors () all showed a higher risk of PJI, but not statistically significantly so for most. This may have been due to sample size. We made multiple comparisons, so caution should be exercised when interpreting the data. It should be noted that even though there were more PJIs in patients with 1 or more risk factors, most of these patients did not develop a PJI, and some of those without any risk factors also had a PJI. We found that preoperative waiting increased the risk of PJI, and this, along with urinary tract infection, remained statistically significant after the logistic regression analysis. It appears that a preoperative stay of more than 24–36 h is associated with unacceptable risk of infection.

The clinical effect of surgical delay in older patients with hip fracture is controversial, and little is known about the effect on the risk of PJI. In a meta-analysis on the effects of early surgery on mortality and complications, none of the studies that were included evaluated PJI (Simunovic et al. Citation2010). An increase in the risk of PJI after 48 h has been described by Ridgeway et al. (Citation2005). Prolonged preoperative waiting time may have medical reasons or may be due to a lack of operation rooms or personnel. From our clinical experience, delays due to medical stabilization or other necessary preoperative procedures are rarely the reasons for prolonged waiting time after admission, but information on the reason for surgical delay was not available for this study.

Increased length of surgery has previously been found to be associated with increased risk of PJI after THR (Ridgeway et al. Citation2005, Dale et al. Citation2009). Garcia-Alvarez et al. (Citation2010) also found a relationship between length of surgery and deep wound infection after hemiarthroplasty, but as far as we know, this has not been reported by others after hemiarthroplasty (Ridgeway et al. Citation2005, Garcia-Alvarez et al. Citation2010). There was no relationship between length of surgery and PJI in our study.

Microbiology

Consistent with what has been published in the literature, CoNS and Staphylococcus aureus were the most frequently isolated organisms in our cohort (Tsukayama et al. Citation1996, Pandey et al. Citation2000, Widmer Citation2001). CoNS strains were present in 7 of the PJIs, 4 of which were methicillin-resistant (MRSE). This is in line with a recent publication about MRSE being increasingly important in PJIs (Stefánsdóttir et al. Citation2009). We found no MRSA in our study, which is consistent with the low incidence of MRSA in Norway (Elstrøm et al. Citation2012). Polymicrobial infections were observed in 5 of 17 cases (). This matches the previous findings of older age being associated with polymicrobial infection (Marculescu and Cantey Citation2008).

Treatment

Soft tissue debridement and retention of the prosthesis is often used to treat acute PJIs. The success rate of debridement and retention of prosthesis in this study was only 5/14, even though all the PJIs were acute and the microbiology did not deviate from other series published. We have previously reported satisfactory results from this treatment with a success rate of 72% in a THR cohort (Westberg et al. Citation2012). The outcome in this series was therefore unexpectedly poor. However, several of these patients had severe illnesses, alcoholism, or impaired cognitive function, which most probably affected the results of the PJI treatment. This may also explain why 5 out of 17 of the patients ended up with a resection arthroplasty. They were not reimplanted because of severe infections or other concomitant morbidity, or because they had conditions that made them unsuitable for a 2-stage procedure. We believe that this reflects how the fracture population differs from the primary THA population. The higher age, the poorer host status, and the traumatic injury may all increase the risk of both PJI and of poor outcome after infection.

Mortality

The 1-year mortality rate in the elderly following hip fracture in Norway has been reported to be 26–29% (Frihagen et al. Citation2007, Figved et al. Citation2009). We found a 1-year mortality rate of 21% in the group without infection, with an increase to 47% in the infection group (p = 0.03). Logistic regression analysis did not confirm an increased mortality rate. It may be due to unknown confounders or a lack of statistical power. Edwards et al. (Citation2008) reported a 1-year mortality rate of 50% in a hip fracture population with SSI following hemiarthroplasty. We found a correlation between having more than 1 known risk factor and PJI, which may support the idea that preoperative medical conditions also contributed to the high mortality rate in the infection group.

In contrast to a previously published meta-analysis (Simunovic et al. Citation2010), preoperative delay was not associated with increased mortality in the present study. This may have been due to several factors. The sample sizes were mostly larger than in our study, ranging from 65 to 3,628 patients. Not only femoral neck fractures and arthroplasties were included, but also trochanteric fractures and femoral neck fractures treated with internal fixation. The cutoff times for operative delay were also often longer than in our study, varying from 24 h up to 5 days. Finally, the effect on mortality was not large in this meta-analysis, and it was only found at 1 year, not at 30 days, 3 months, or 6 months.

Limitations

The present study had several limitations. Firstly, it was a retrospective single-center study with a potential for selection bias. The retrospective chart review made the diagnosis and classification of PJI less certain, and the numbers may have been underestimated or overestimated. Secondly, the conclusions may have been limited by the study being observational. Finally, relatively few patients were included and a small number of PJIs were identified. Thus, it is possible that additional risk factors would have been detected if the number of infections had been larger.

In conclusion, our main findings were that there is a high incidence of PJI (9%) in this elderly population receiving an arthroplasty after hip fracture, with possibly devastating outcome. Furthermore, our data suggest that reducing preoperative stay may reduce PJI and hence mortality.

Supplementary data

Table 5 is available at our website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 5748.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (105.2 KB)MW initiated the study, collected the data and wrote the manuscript. MW and FF performed the data analysis. All authors contributed to the final paper and critically reviewed it.

We are grateful to Dr Anders Walløe and Dr Bjarne Grøgaard of the Department of Orthopaedics, Oslo University Hospital, for their contributions and to Are Hugo Pripp of the Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Oslo University Hospital, for statistical advice.

No competing interests declared.

- Bhandari M, Deveraux PJ, Swiontkowski MF, Tornetta P, Obremskey W, Koval K, Nork S, Sprague S, Schemitsch EH, Guyatt GH. Internal fixation compared with arthroplasty for displaced fractures of the femoral neck. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2003; 85 (9): 1673-81.

- Bhandari M, Deveraux PJ, Tornetta P 3, Swiontkowski MF, Berry DJ, Haidukewych G, Schemitsch EH, Hanson BP, Koval K, Dirschl D, Leece P, Keel M, Petrisor B, Heetveld M, Guyatt GH. Operative management of displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients: an international survey. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005; 87: 2122-30.

- Dale H, Hallan G, Espehaug B, Havelin LI, Engesaeter LB. Increasing risk of revision due to deep infection after hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (6): 639-45.

- Dale H, Skråmm I, Løwer HL, Eriksen HM, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Skjeldestad FE, Havelin LI, Engesaeter LB. Infection after primary hip arthroplasty. A comparison of 3 Norwegian health registers. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (6): 646-54.

- Edwards C, Counsell A, Boulton C, Moran CG. Early infection after hip fracture surgery. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008; 90: 770-7.

- Elstrøm P, Kacelnik O, Bruun T, Iversen B, Hauge SH, Aavitsland P. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Norway, a low-incidence country. 2006-2010. J Hosp Infect 2012; 80 (1): 36-40.

- Figved W, Opland V, Frihagen F, Jervidalo T, Madsen JE, Nordsletten L. Cemented versus uncemented hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures. Clin Orthop 2009; (467) (9): 2426-35.

- Frihagen F, Nordsletten L, Madsen JE. Hemiarthroplasty or internal fixation for intracapsular displaced femoral neck fractures: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007; 335: 1251-4.

- Garcia-Alvarez F, Al-Ghanem R, Garcia-Alvarez I, Lopez-Baisson A, Bernal M. Risk factors for postoperative infections in patients with hip fracture treated by means of Thompson arthroplasty. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2010; 50: 51-5.

- Kurtz SM, Lau E, Schmier J, Ong KL, Zhao K, Parvizi J. Infection burden for hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty 2008; 23 (7): 984-91.

- Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control 1999; 27 (2): 97-132.

- Marculescu CE, Cantey JR. Polymicrobial prosthetic joint infections: risk factors and outcome. Clin Orthop 2008; (466) (6): 1397-404.

- Pandey R, Berendt AR, Athanasou NA. Histological and microbiological findings in non-infected and infected revision arthroplasty tissues. The OSIRIS Collaborative Study Group. Oxford Skeletal Infection Research and Intervention Service. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2000; 120 (10): 570-4.

- Parker MJ, Gurusamy K. Internal fixation versus arthroplasty for intracapsular proximal femoral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 18 (4): CD001708.

- Partanen J, Syrjala H, Vahanikkila H, Jalovaara P. Impact of deep infection after hip fracture surgery on function and mortality. J Hosp Infect 2006; 62: 44-9.

- Phillips JE, Crane TP, Noy M, Elliott TS, Grimer RJ. The incidence of deep prosthetic infections in a specialist orthopaedic hospital: a 15-year prospective survey. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006; 88: 943-8.

- Ridgeway S, Wilson J, Charlet A, Kafatos G, Pearson A, Coello R. Infection of the surgical site after arthroplasty of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2005; 87: 844-50.

- Rogmark C, Carlsson A, Johnell O, Sernbo I. A prospective randomised trial of internal fixation versus arthroplasty for displaced fractures of the neck of the femur. Functional outcome for 450 patients at two years. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2002; 84 (2): 183-8.

- Simunovic N, Devereaux PJ, Sprague S, Guyatt GH, Schemitsch EH, DeBeer J, Bhandari M. Effect of early surgery after hip fracture on mortality and complications: systemic review and meta-analysis. Can Med Ass Jl 2010; 182 (15): 1609-16.

- Stefánsdóttir A, Johansson D, Knutson K, Lidgren L, Robertsson O. Microbiology of the infected knee arthroplasty: Report from the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register on 426 surgically revised cases. Scand J Infect Dis 2009; 41: 831-40.

- Tsukayama DT, Estrada R, Gustilo RB. Infection after total hip arthroplasty. A study of the treatment of one hundred and six infections. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1996; 78 (4): 512-23.

- Westberg M, Grøgaard B, Snorrason F. Early prosthetic joint infections treated with debridement and implant retention. 38 primary hip arthroplasties prospectively recorded and followed for median 4 years. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (3): 227-32.

- Widmer AF. New developments in diagnosis and treatment of infection in orthopedic implants. Clin Infect Dis (Suppl 2) 2001; 33: 94-106.