Abstract

Background and purpose Tourniquet-related nerve injuries remain a concern in orthopedic surgery. The cuff pressures used today are generally lower, and therefore a decreasing incidence of peripheral nerve injuries might also be expected. However, there have been few neurophysiological studies describing the outcome after bloodless field surgery. We describe the results of neurophysiological examinations and report the incidence of nerve injuries after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in a bloodless field.

Patients and methods This study was part of a prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial in patients scheduled for TKA in a bloodless field. 20 consecutive patients were enrolled. Electroneurography (ENeG) and quantitative sensory testing (QST) of thermal thresholds were performed on day 3. These tests were repeated 2 months after surgery when electromyography (EMG) with a concentric-needle electrode was also performed.

Results The mean tourniquet cuff pressure was 237 (SD 33) mmHg. Electromyographic signs of denervation were found in 1 patient, who also had the highest cuff pressure in the study population (294 mmHg). The sensory nerve response amplitudes were lower in the operated leg on day 3; otherwise, the neurophysiological examinations showed no differences between the legs.

Interpretation When low tourniquet cuff pressures are used the risk of nerve injury is minor.

Nerve injuries, such as peroneal nerve palsy, after a total knee arthroplasty (TKA) can be a devastating complication (Nercessian et al. Citation2005). However, the reported incidence and the severity of nerve injuries vary—ranging from a mild transient loss of function to permanent, irreversible damage (Noordin et al. Citation2009). The symptoms reported may not reflect the true incidence of complications; minor nerve injuries are diagnosed by electrodiagnostic tests such as EMG or nerve conduction studies. Suggested risk factors are valgus deformity, flexion contracture, pre-existing neuropathy, rheumatoid arthritis, hematoma, postoperative epidural analgesia, and pneumatic tourniquet (Idusuyi and Morrey Citation1996, Schinsky et al. Citation2001, Nercessian et al. Citation2005). The use of a pneumatic tourniquet may be helpful during TKA surgery, but it involves a risk , of nerve injury (Smith and Hing Citation2010, Tai et al. Citation2011, Alcelik et al. Citation2012).

The 2 main mechanisms of pneumatic tourniquet-induced nerve injury are ischemia and direct mechanical effects (Hodgson Citation1994). Ochoa et al. (1972) found that compressive neurapraxia rather than ischemic neuropathy or muscle damage was the underlying cause of tourniquet paralysis. They described paranodal myelin invagination as the pathophysiological mechanism of nerve injury after tourniquet use. When a lower tourniquet cuff pressure and a shorter duration have been used, this mechanism has been difficult to confirm (Pedowitz et al. Citation1991). Nitz et al. (Citation1989) suggested that tourniquet compression is associated with increased microvascular permeability and intraneural edema, with persistent tissue ischemia and subsequent nerve degeneration. Hodgson (Citation1994) suggested that increased tourniquet time increases the probability of an injury, the severity of which will be primarily determined by the tourniquet cuff pressure. Today, tourniquet cuff pressures are usually lower, and fewer nerve injuries might be expected. However, there is a need for further neurophysiological studies to determine whether this is the case (Younger et al. Citation2011).

The main aim of this study was to determine the incidence of nerve injuries related to the use of bloodless field after TKA. A secondary aim was to analyze the results of neurophysiological examinations in this patient group

Patients and methods

Patients

This study was part of a randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT) in patients scheduled for a primary TKA in a bloodless field (Olivecrona et al. Citation2012). In that particular study we investigated whether measuring the limb occlusion pressure would lead to lower tourniquet cuff pressure and if this would lead to less postoperative pain and wound complications. In that study, patients aged 75 years or younger and classified according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) as ASA 1–3 were considered to be eligible for inclusion. Patients with a systolic blood pressure of over 200 mmHg and those with a thigh girth of over 78 cm were excluded. 164 patients gave their informed consent to participate, and were randomized preoperatively to a control group (routine method) or to an intervention group (limb occlusion pressure, LOP). All the patients were given written and verbal information and they were also informed that 10 patients from each randomization group would be asked to participate in neurophysiological examinations postoperatively on day 3 and then again 2 months after their surgery. Patients with diabetes mellitus or spinal disorders and those who had received chemotherapy or had a body mass index (BMI) of > 30 were also excluded from this neurophysiological study. The neurophysiologist who performed the examinations was blinded regarding the allocation group and to any information about tourniquet use or any clinical nerve symptoms from the operated leg.

20 patients were enrolled in this neurophysiological study between November 2009 and June 2010. 2 patients were excluded after inclusion: one with a BMI of 40 who was incorrectly included, and one who decided to drop out after the first examination.

Neurophysiological examinations

Electroneurography (ENeG) was performed bilaterally with surface electrodes according to the standard routine at the Karolinska Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, using a Nicolet VikingSelect EMG system (Care Fusion, Middleton, WI) Where necessary, the limbs were warmed with heating bags to keep the skin temperature at 32˚C. Motor nerve conduction studies in the peroneal and the tibial nerves included conduction velocity from knee level to ankle (in m/s), distal latency from ankle to the extensor digitorum brevis muscle and the abductor hallucis muscle, respectively (in ms), muscle response amplitude to distal stimulation (in mV), and also F-wave latencies in both nerves (ms). The peroneal nerve motor conduction velocity was also calculated for the segment across the fibular head. Sensory nerve conduction studies were done on the superficial peroneal nerve and the sural nerve (conduction velocity in m/s and amplitude in µV).

Concentric-needle electrode electromyography (EMG) was performed bilaterally using the same equipment. EMG activity was studied in the vastus lateralis muscle in the thigh, and in the anterior tibial and medial head of the gastrocnemius muscles in the lower limbs. We looked for spontaneous fibrillations and positive sharp waves signaling ongoing denervation, for changes in motor unit configuration, and for diminished activity at maximal voluntary contraction.

Quantitative sensory tests (QSTs) were performed using the Medoc TSA-II Neurosensory Analyzer (Medoc Ltd., Ramat Yishai, Israel) and included determinations of temperature thresholds anteriorly at the middle of the lower legs and on the dorsum of the feet. The method of limits was used. The temperature was changed by 1°C/s.The results were also expressed as the value for the neutral zone (°C) that is the difference between thresholds for warmth and cold. Differences between the operated leg and the unoperated leg were calculated at both visits. At the second visit, the test results were also compared with results from the first study.

The neurophysiological tests were planned as a wide approach to discover any intraoperative nerve injury (Aminoff Citation2004). However, several of the measurements were made below the knee and thus on nerve sections not directly involved in the tourniquet area or the surgical field. F-waves were obtained by nerve stimulation at the ankle. The volley of nerve impulses initiated by electrical nerve stimulation will travel antidromically (“backwards”) in the motor nerve fibers up to the spinal cord, so as to depolarize the spinal motor neurons, leading to many impulses bouncing back down the leg to give a twitch in the foot muscles. Thus, these nerve impulses pass the knee and the thigh twice, and a small change in nerve conduction might be doubled and thereby easier to reveal. An injury to the motor nerve fibers might appear as an increase in latency and/or a reduction in persistence, i.e. fewer impulses return to the foot muscles. We therefore analyzed these responses in more detail.

ENeG and QST were performed on day 3 and after 2 months postoperatively, while EMG was performed only after 2 months.

All patients were followed up by phone 18 months after the examinations in order to find out if any of them had any clinical symptoms of nerve injury.

Statistics

The number of patients included was chosen based on earlier studies with EMG examinations where 20–25 patients had been included (Saunders et al. Citation1979, Weingarden et al. Citation1979, Dobner and Nitz Citation1982, Arciero et al. Citation1996).

Continuous variables are presented as mean (SD) or median (minimum and maximum). The scale variables were tested with the non-parametric Wilcox test because of the small number of patients included and the risk regarding the assumption of normality. The medians of the differences are estimated with the Hodges-Lehmann estimator and presented with a 95% confidence interval (CI). All tests were two-sided and the results were considered significant at p-values of < 0.05. For the statistical analysis, PASW (SPSS) version 18 was used.

Ethics and registration of the study

The study was conducted according to the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, on July 3, 2009 (ref. no. 2007/757-31/1-4, 2007/1164-32) and registered at ClinicalTrial.gov (NCT01442298).

Results

Mean tourniquet cuff pressure (TCP) was 237 mmHg and mean tourniquet time was 81 min. The 9 patients from the LOP group had a mean TCP of 223 (41) mmHg and the 9 controls had a mean TCP of 251 (12) mmHg ().

Table 1. Demographic baseline data for all patients included (n = 18)

Electromyographic signs of recent denervation were found in 1 patient (no. 16). At 2 months, this patient had fibrillations in the vastus lateralis and the gastrocnemius muscles, associated with reduced voluntary activity. Studies in the peroneal nerve at 3 days and at 2 months showed a reduction in response amplitude, a prolongation of F-wave latency, and a reduction in F-wave persistence. No abnormalities were found in the unoperated leg. This patient had the highest cuff pressure in the study, 294 mmHg for 100 min. In 3 other patients (nos. 17, 18, and 20) EMG revealed minor signs of chronic changes with motor unit potentials showing increased duration and amplitude. These patients had no signs of ongoing denervation. 5 patients had one or more minor deviations in electroneurography or QST values (nos. 1, 7, 8, 9, and 17) that might indicate a change in nerve function related to the operation. However, the deviations were small and were not considered to be definite signs of recent nerve injury. The cuff pressures in these 5 patients ranged from 173 to 280 mmHg. None of these patients showed any clinical symptoms of nerve damage.

The analysis of the patients as a group showed no statistically significant difference in motor or sensory conduction velocity when operated and unoperated legs were compared. Motor response amplitudes in the peroneal nerve on day 3 were slightly lower in the operated leg. The median of differences between operated leg and control leg was 0.5 mV (CI: –0.1 to 1.9) (p = 0.1) on day 3 and 0.3 mV (–0.5 to 1.2) (p = 0.5) at 2 months. This slightly lower—although not statistically significant—response amplitude was not seen in the tibial nerve. Sensory nerve amplitudes were lower in the operated leg on day 3 for both the sural (2 (0.5–4) µV; p = 0.01) and the superficial peroneal nerve (1.5 (0 – 3) µV; p = 0.06) and at 2 months (sural nerve 2.5 (0–5) µV; p = 0.04; and superficial peroneal nerve 1 (–0.5 to 2.5) µV; p = 0.08).

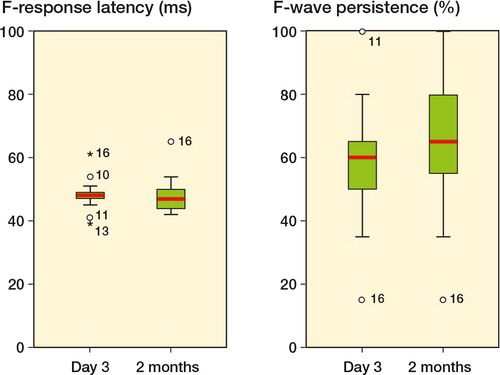

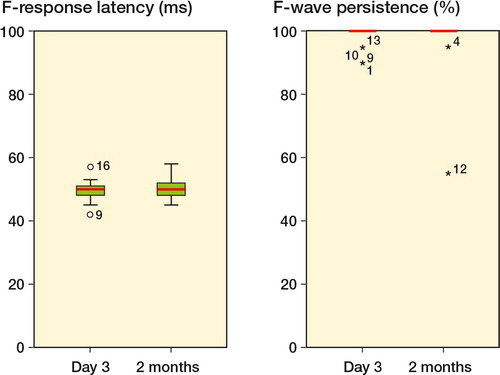

There was no statistically significant difference in F-wave latencies and persistencies between day 3 and 2 months (data not shown), or between the operated and unoperated leg (, and 3). The patient with electromyographic signs of denervation (no. 16) showed prolonged F-wave latency and a reduction in F-wave persistence in the peroneal nerve both on day 3 and at 2 months postoperatively. An increase in latency in the tibial nerve was seen only on day 3.

Table 2. Results of F-wave studies in the operated leg and median of the differences between the unoperated and the operated leg on day 3 and 2 months postoperatively

Figure 1. F-wave latency (in ms) and F-wave persistence (%) in the peroneal nerve in the operated leg both at day 3 and 2 months postoperatively. Patient no. 16 had EMG-confirmed nerve injury and the highest cuff pressure of 294 mmHg.

Figure 2. F-wave latency (in ms) and F-wave persistence (%) in the tibial nerve in the operated leg both at day 3 and 2 months postoperatively. Patient no. 16 had EMG-confirmed nerve injury and the highest cuff pressure of 294 mmHg. Patient no. 12 had the longest bloodless field duration of 122 minutes.

The thresholds for heat and cold perception (QST) showed no statistically significant differences between the operated leg and the unoperated leg (data not shown).

In a telephone follow-up of 15 of the patients included, only the patient with an EMG-evident denervation reported radiating pain and a tingling sensation in the operated leg and foot for about 6 months after the operation, after which the symptoms disappeared. None of the other patients had had any similar symptoms.

Discussion

In this study, the mean TCP was 237 (33) mmHg, which appears to be a safe cuff pressure regarding the risk of nerve injuries. Only one patient had clinical and EMG evidence of nerve injury, and this patient had a cuff pressure of 294 mmHg—which is a rather high pressure, but still within recommended limits. Denervation in both the thigh and the lower leg supports the view that the injury was caused by the tourniquet and not by the surgical procedures at knee level.

Chronic neurogenic EMG changes were seen in 3 patients. The cause was unknown, and we regarded it as being unrelated to the surgery since there were no signs of ongoing denervation.

A study conducted in the 1980s reported that two-thirds of patients who had undergone knee surgery in a bloodless field showed electromyographic (EMG) evidence of denervation and a functional capacity of one third of the unoperated leg. The control group was operated on without a bloodless field, and showed no evidence of denervation and had a functional capacity of four-fifths (Dobner and Nitz Citation1982). In that study, the mean TCP was 393 (300–450) mmHg and the mean bloodless field time was 42 (8–90) min. Our neurophysiological results contrast with that study, which may be due to the fact that we had a mean cuff pressure of 237 (33) mmHg. Today’s lower TCPs mean that these older studies with cuff pressures of up to 450 mmHg are no longer relevant.

In a retrospective questionnaire survey, 265 orthopedic surgeons in Norway were asked to report any complications due to tourniquet use during the previous 2 years. 12 clinically evident nerve complications in the lower limb were reported, with an overall incidence of 0.03% (Odinsson and Finsen Citation2006). In our RCT study population of 164 patients, 2 patients were scheduled for EMG/ENeG examinations because they had clinical symptoms at the follow-up 2 months after surgery. 1 patient had minor signs of an injury of the tibial nerve and 1 additional patient had EMG-confirmed denervation in muscles innervated by the peroneal nerve. Together with 1 patient with a nerve injury from this study, this gives an incidence of 2%. This variation in incidence of nerve injuries has been shown and discussed earlier. We want to draw attention to the important differences in study design, ranging from prospective neurophysiological examination of a whole study population to a retrospective report of clinically evident nerve injuries.

Horlocker et al. (2006) reported a strong correlation between nerve injuries and prolonged tourniquet time. They studied 1,001 patients who underwent a primary or revision knee replacement, with a mean tourniquet time of 145 (25) min. Clinical neurological complications were noted in 7.7%. Odinsson and Finsen (Citation2006) reported that 2 of the major complications occurred with tourniquet times of 130 and 180 min. Since we had a mean bloodless field time of 81 min with a longest duration of 122 min, our material is not comparable to theirs. A correlation between nerve injury and tourniquet time was also found in another retrospective 20-year cohort study of 11,645 TKA patients (OR = 1.3; p = 0.003). Unfortunately, no data on the duration of tourniquet time were presented (Jacob et al. Citation2011). In their study, Saunders et al. (Citation1979) showed a distinct difference between patients with short tourniquet time, i.e. less than 15 min—with 22% EMG abnormalities—and patients with more than 60 min of bloodless field time, 85% of whom had EMG abnormalities. We did not find such a difference, but on the other hand none of the patients in our study had a tourniquet time shorter than 63 min. The high incidence of EMG abnormalities in the study by Saunders et al. could have been due to the high TCPs of 350–450 mmHg, regardless of tourniquet time.

Sensory nerve examinations showed differences between the operated leg and the unoperated leg. We were surprised because this might be interpreted as an axonal injury, which is a more severe injury than a local demyelination. None of the patients appeared to be troubled by or even noticed any sensory loss. Nor was this something that was noticed at the clinical follow- up. However, technical considerations such an edema in the operated leg may have affected the results.

Our quantitative sensory test results support the results of earlier studies indicating that small myelinated and non-myelinated fibers are not as sensitive to compression as large myelinated fibers (Dahlin et al. Citation1989, Nitz and Matulionis, Citation1982).

One limitation of our study was that the number of patients was rather small, even though it was comparable with other studies. On the other hand, the neurophysiological series was large enough for the statistical analysis. The strengths of the present study were that it was a consecutive series of well-described patients who were examined with both EMG and ENeG after TKA surgery in a bloodless field. As far as we know, there have been no other studies published in which this type of broad protocol has been used.

We conclude that TCPs of around 240 mmHg for up to 80 min appear to be safe regarding the risk of nerve injury in patients undergoing TKA in a bloodless field.

CO: study design, inclusion of patients, data analysis, follow-up, and writing of the manuscript. RB and SP: study design and provision of feedback on the manuscript. BRS: study design, neurophysiological examinations, and provison of feedback on the manuscript. BYN: study design, neurophysiological examinations, recording of data, data analysis, and provision of feedback on the manuscript.

We thank Lena Bergqvist, registered neurophysiology technician, who organized and performed most of the electroneurography examinations. The first author was given time for research work by the Department of Orthopedics, Södersjukhuset, Stockholm. The examinations carried out were financed by funds from the Karolinska Institute.

No competing interests declared.

- Alcelik I, Pollock RD, Sukeik M, Bettany-Saltikov J, Armstrong PM, Fismer P. A comparison of outcomes with and without a tourniquet in total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27 (3): 331-40.

- Aminoff MJ. Electrophysiologic testing for the diagnosis of peripheral nerve injuries. Anesthesiology 2004; 100 (5): 1298-303.

- Arciero RA, Scoville CR, Hayda RA, Snyder RJ. The effect of tourniquet use in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A prospective, randomized study. Am J Sports Med 1996; 24 (6): 758-64.

- Dahlin LB, Shyu BC, Danielsen N, Andersson SA. Effects of nerve compression or ischaemia on conduction properties of myelinated and non-myelinated nerve fibres. An experimental study in the rabbit common peroneal nerve. Acta Physiol Scand 1989; 136 (1): 97-105.

- Dobner JJ, Nitz AJ. Postmeniscectomy tourniquet palsy and functional sequelae. Am J Sports Med 1982; 10 (4): 211-4.

- Hodgson AJ. A proposed etiology for tourniquet-induced neuropathies. J Biomech Eng 1994; 116 (2): 224-7.

- Idusuyi OB, Morrey BF. Peroneal nerve palsy after total knee arthroplasty. Assessment of predisposing and prognostic factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996; 78 (2): 177-84.

- Jacob AK, Mantilla CB, Sviggum HP, Schroeder DR, Pagnano MW, Hebl JR. Perioperative nerve injury after total knee arthroplasty: regional anesthesia risk during a 20-year cohort study. Anesthesiology 2011; 114 (2): 311-7.

- Nercessian OA, Ugwonali OF, Park S. Peroneal nerve palsy after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2005; 20 (8): 1068-73.

- Nitz AJ, Matulionis DH. Ultrastructural changes in rat peripheral nerve following pneumatic tourniquet compression. J Neurosurg 1982; 57 (5): 660-6.

- Nitz AJ, Dobner JJ, Matulionis DH. Structural assessment of rat sciatic nerve following tourniquet compression and vascular manipulation. Anatomical Rec 1989; 225: 67-76.

- Noordin S, Mcewen JA, Kragh JF, Jr., Eisen A, Masri BA. Surgical tourniquets in orthopaedics. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91 (12): 2958-67.

- Odinsson A, Finsen V. Tourniquet use and its complications in Norway. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006; 88 (8): 1090-2.

- Olivecrona C, Ponzer S, Hamberg P, Blomfeldt R. Lower tourniquet cuff pressure reduces postoperative wound complications after total knee arthroplasty. A randomized controlled study of 164 patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2012; 94 (24): 2216-21.

- Pedowitz RA, Nordborg C, Rosenqvist AL, Rydevik BL. Nerve function and structure beneath and distal to a pneumatic tourniquet applied to rabbit hindlimbs. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 1991; 25 (2): 109-20.

- Saunders KC, Louis DL, Weingarden SI, Waylonis GW. Effect of tourniquet time on postoperative quadriceps function. Clin Orthop 1979; (143): 194-9.

- Schinsky MF, Macaulay W, Parks ML, Kiernan H, Nercessian OA. Nerve injury after primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2001; 16 (8): 1048-54.

- Smith TO, Hing CB. Is tourniquet beneficial in total knee replacement surgery? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Knee 2010; 17 (2): 141-7.

- Tai TW, Lin CJ, Jou IM, Chang CW, Lai KA, Yang CY. Tourniquet use in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011; 19 (7): 1121-30.

- Weingarden SI, Louis DL, Waylonis GW. Electromyographic changes in postmeniscectomy patients. Role of the pneumatic tourniquet. JAMA 1979; 241 (12): 1248-50.

- Younger AS, Manzary M, Wing KJ, Stothers K. Automated cuff occlusion pressure effect on quality of operative fields in foot and ankle surgery: a randomized prospective study. Foot Ankle Int 2011; 32 (3): 239-43.