Abstract

Background In children with angulating deformities of the lower limbs, hemiepiphysiodesis can be used to guide growth to achieve better alignment at skeletal maturity. Traditionally, this has been performed with staples. The tension-band plating technique is new and it has been advocated because it is believed to reduce the risk of premature closure of the growth plate compared to stapling. The benefit of the tension-band plating technique has not yet been proven in experimental or randomized clinical studies.

Methods We performed a randomized clinical trial in which 26 children with idiopathic genu valgum were allocated to stapling or tension-band plating hemiepiphysiodesis. Time to correction of the deformity was recorded and changes in angles on long standing radiographs were measured. Pain score using visual analog scale (VAS) was recorded for the first 72 h postoperatively. Analgesics taken were recorded by the parents.

Results Mean treatment times for stapling hemiepiphysiodesis (n = 10) and for tension-band plating hemiepiphysiodesis (n = 10) were similar. Postoperative VAS scores and consumption of analgesics were also similar in both groups. No hardware failure or wound-related infection was observed.

Interpreatation Treatment time for the 2 treatment modalities was not significantly different in this randomized clinical trial. Tension-band plating and stapling appeared to have a similar effect regarding correction of genu valgum. We cannot rule out type-II error and the possibility that our study was underpowered.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01641354.

Correction of excessive angulating deformities of the extremities is a common procedure in pediatric orthopedics. In the child with significant growth remaining, hemiepiphysiodesis is often used to treat angular deformities of the knee. Transient growth guidance is obtained by unilateral inhibition of the growth plate until the deformity is corrected. The implants are then removed to allow resumption of natural growth. In 1949, Blount and Clarke first reported stapling of the epiphyseal plate as a method for controlling growth disturbances such as angular deformities. In clinical series, stapling appears to be a safe procedure (Stevens et al. Citation1999, Courvoisier et al. Citation2009), although the technique might have some complications such as staple migration or breakage, and the potential for premature closure of the growth plate (Blount and Clarke Citation1949).

The tension-band plating technique has been advocated to avoid compression of the growth plate and to reduce mechanical failures (Stevens Citation2007). With this technique, a small plate is applied extra-periosteally and fixated by 1 screw on each side of the growth plate. The screws are not rigidly fixed in the plate and can angulate progressively as the deformity is corrected. An approximately 30% faster correction rate was noted in a recent paper based on a retrospective follow-up investigating 34 children with 65 deformities (Stevens Citation2007). In comparison, another retrospective study comparing tension-band plating and stapling failed to show a faster correction based on 63 interventions in 38 children (Wiemann et al. Citation2009). Failure of the implants used for tension-band plating has also been reported (Schroerlucke et al. Citation2009, Burghardt et al. Citation2010).

To our knowledge, the advantages of the tension-band plating technique over stapling have not yet been proven in randomized clinical trials. We present a randomized trial involving children treated for idiopathic genu valgum (IGV) deformity who were allocated to medial epiphysiodesis by either stapling or tension-band plating of the distal femur. We compared the clinical and radiographic effects of stapling with those of tension-band plating in a group of children with IGV.

Children and methods

Design

The children included in the study were randomized to either medial tension-band plating or stapling of the distal femoral growth plate. After randomization, the 2 groups of children were followed in the same way with regular examinations in the outpatient clinic. The minimum time between visits to the clinic was 3 months. Inclusion began in May 2009 and ended in November 2011. The children were followed up until implant removal. The follow-up period ended in May 2012. The study was conducted at the Department of Children’s Orthopaedics at Aarhus University Hospital (AUH) and the Department of Orthopaedics at Hospital Unit West (HUW). The primary outcome was treatment time and the secondary outcome was pain score postoperatively.

Statistical considerations

Extrapolation of data from Stevens’ treatment of IGV with tension-band plating gives a mean treatment time to correction of 9 months and a standard deviation of 3 months (Stevens Citation2007). The mean treatment time with staples would be expected to be at least 13 months. The desired power was 80% and α = 0.05. The desired sample size based on these assumptions was 11 children in each group.

Ethics

The study was performed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Central Denmark Region Committees on Biomedical Research Ethics (M-20080147).

Inclusion

Children aged 8–15 years with IGV were assessed for eligibility in the clinic by the operating surgeons. The condition had to limit daily activities and at least 7 cm of intermalleolar distance was needed before intervention was considered. At least 6 months of estimated remaining growth was needed.

Exclusion

Children who had underlying systemic disease were not included in the study.

Randomization

The operating surgeons assigned the participants to intervention. 26 envelopes were prepared for randomization: 13 for stapling and 13 for tension-band plating. A person not affiliated with the project mixed and numbered the envelopes in random order. All operating surgeons (at AUH: 4; at HUW: 2) were familiar with both stapling and tension-band plating.

Pain score

Visual analog scale (VAS) was used to evaluate postoperative pain. It has been shown that VAS can be used in children after lower-extremity surgery (McNeely and Trentadue, Citation1997). All parents received charts to record VAS twice a day (in the morning and evening) for 72 h. We used a standardized postoperative pain treatment in all patients ().

Table 1. Pain-control regime

Surgical technique

Both stapling and tension-band plating were performed according to the guidelines of the manufacturing companies. Under fluoroscopic guidance, the medial aspect of the distal femoral growth plate was identified. Using longitudinal incisions, subcutaneous tissue was divided. Implants were placed extraperiosteally. Children randomized to stapling had 3 staples placed across the physis (chromium-cobalt steel, Large; Smith and Nephew, Memphis, TN). In the tension-band plating group, 1 plate with 2 cannulated screws was placed spanning the growth plate (8-plate system; 16-mm titanium plate and 32-mm cannulated titanium screws; Orthofix, McKinney, TX). The wound was closed in layers and a dressing applied. Immediate weight bearing was allowed.

Follow-up

14 days after surgery, the children were seen in the outpatient clinic. Radiographs of the knees were taken to document implant placement. VAS scoring results and consumption of analgesics were documented in the charts. Thereafter, the children were seen regularly with the time between visits being reduced at the end of treatment.

Long standing radiographs

1 standing anterior-posterior recording was taken with both lower extremities exposed at the same time. Before recording this image, an exact lateral image was obtained using fluoroscopy with the posterior part of the femoral condyles being used as reference. A footprint was drawn on the floor to be able to reproduce the limb position for the final radiograph. All knee joints were fully extended to minimize the risk of unwanted rotation of the knee. A distance of 3.5 m was chosen to minimize parallel axis error. The beam was centered at the level of the knees. Images were saved in the Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS). Calculations were performed on a workstation using software connected to the PACS (IMPAX 6.3.1.3811; Agfa, Mortsel, Belgium). The mechanical axis deviation (MAD), lateral distal femoral angle (LDFA), and medial proximal tibial angle (MPTA) were measured according to principles outlined by Paley and Tetsworth (Citation1992). 2 different observers performed the measurements independently on the radiographs twice, with at least 1 month between measurements. Interobserver reliability for LDFA, MPTA, and MAD was calculated with ICC coefficients ranging from 92% to 97%, 83% to 84%, and 99% to 100%, respectively. Concerning intraobserver reliability, the corresponding ICC coefficients for LDFA, MPTA, and MAD were 98%, 90%, and 100 %. ICC coefficients > 80% can be viewed as reflecting good reliability. The primary measurements (performed by MBH) were used for statistical analysis.

Statistics

Data (treatment time, LDFA, MPTA, MAD, IM, VAS, and analgesic consumption) were assessed for normality on plots and by the Shapiro-Wilks test. Student’s t-test was used to compare variables. Any p-values (2-tailed) of < 0.05 were considered to be significant. Mean values with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used. The Intercooled Stata statistical analysis package version 11.2 was used for statistical computations.

Results

The main finding in this randomized controlled trial was that time taken to correct idiopathic genu valgum deformity was not statistically significantly different with staples and with tension-band plating in the trial population (). All 20 children who completed the study achieved full correction of the genu valgum deformity. No cases of implant failure, infection, or growth arrest were noted in the study. The groups differed regarding sex (M/F: 3/7 in the stapling group and 8/2 in tension-band plating group). The children treated with tension-band plating were slightly younger (mean age 10.1 (range 8–14) years) than the children treated with staples (mean age 11.1 (range 6–13) years) at the time of surgery. No statistically significant differences were found between groups regarding age, treatment time, preoperative intermalleolar distance, and measured radiographic values (LDFA, MPTA, and MAD) on long standing radiographs taken before treatment and at the end of treatment ( and ).

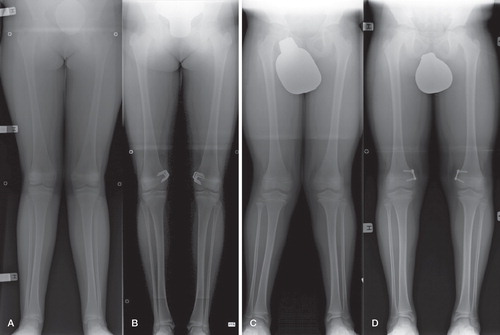

A. Genu valgum prior to medial stapling of the distal femoral physes.

B. Before removal of implants.

C. Genu valgum prior to medial hemiepiphysiodesis of the distal femoral physes using the tension-band plating technique.

D. Correction of genu valgum before removal of implants.

Table 2. Treatment times and measurements of IM distance. Values are mean (CI)

Table 3. Radiographic measurements on long standing radiographs. Mean values between the left and right side are given. Values are mean (CI). Negative MAD values describe lateral deviation of the mechanical axis (valgus) and positive values describe medial deviation of the mechanical axis (varus)

The estimated effect size established as Cohen’s delta ((349 – 340) / 120) was 0.075.

VAS score results and registration of analgesics were returned for 18 of the 20 children and they were similar between groups. 1 child operated with tension-band plating experienced rebound growth with an intermalleolar distance of 8 cm measured 15 months after removal of hardware. New long standing radiographs were taken, and partial return of the genu valgum deformity was seen. The child was scheduled for new surgery.

Discussion

The tension-band plating technique using the 8-plate system or similar implants has gained widespread popularity, but there is little evidence to support the superiority of this technique over stapling. In this randomized trial, we did not find any significant differences between the 2 techniques in time to correct the deformity, intermalleolar distance, and measurements on long standing radiographs. Furthermore, no differences were found between groups regarding VAS score or analgesic consumption after surgery. The effect size of 0.075 in relation to treatment time is a small number, and this indicates that the study was underpowered. However, a 30% faster correction rate as previously reported with tension-band plating (Stevens Citation2007) seems unlikely given our data. Our results may have been influenced by gender-related issues because more girls were operated with tension-band plating technique than boys, for whom staples were more often used. It is not known whether the response to hemiepiphysiodesis differs between sexes.

The use of tension-band plating for guided growth has been the subject of several recent clinical papers (Stevens Citation2007, Burghardt et al. Citation2008, Wiemann et al. Citation2009, Burghardt and Herzenberg, Citation2010, Ballal et al. Citation2010, Niethard et al. Citation2010, Jelinek et al. Citation2012). Faster correction was initially reported in 1 retrospective study when using tension-band plating compared to stapling (Stevens Citation2007). In contrast to this, time to correct the deformity appears to have been equal when tension-band plating and stapling were compared in other papers (Wiemann et al. Citation2009, Burghardt and Herzenberg, Citation2010, Niethard et al. Citation2010, Jelinek et al. Citation2012).

Overall, the TBP technique appears to be safe. In favor of tension-band plating is the short operating time, which was documented in a recent paper (Jelinek et al. Citation2012). Furthermore, surgical exposure is probably minimized using tension-band plating; only 1 implant is inserted with this technique—in contrast to stapling, where 3 implants have traditionally been used to span the growth plate (Blount and Clarke Citation1949). Stapling has previously been reserved for adolescents, as several authors believed that this intervention could lead to permanent physeal closure (Frantz Citation1971, Zuege et al. Citation1979, Fraser et al. Citation1995). In a series of 25 children below the age of 10 years who were treated with stapling for valgus or varus deformity, no signs of premature physeal closure were observed (Mielke and Stevens Citation1996). The children were not followed until skeletal maturity, however. It has been suggested that overall, the tension-band plating technique carries less risk of early physeal closure than stapling (Stevens Citation2006, Citation2007). This can very well be attributed to the fact that the periosteum can be damaged during staple insertion or removal. Insertion of staples below the periosteum has been shown experimentally to induce growth arrest and formation of physeal bars (Aykut et al. Citation2005). Because the children were only followed to implant removal in that study, the subject of premature physeal closure was not addressed. A future study should look into this matter.

Complications of the tension-band plating technique have been published, and they are most often associated with treatment of the pathological physis as in Blount’s disease and skeletal dysplasia (Schroerlucke et al. Citation2009, Burghardt et al. Citation2010). The complication rate has been reported to be the same with staples and tension-band plating in 2 previous studies (Wiemann et al. Citation2009, Jelinek et al. Citation2012). One reason for the overall outcome of stapling and tension-band plating appearing equal could be that the biological effect of both techniques is quite similar, despite a theoretical advantage in favor of tension-band plating. Several experimental studies have compared the techniques in both rabbit and porcine models (Mast et al. Citation2008, Goyeneche et al. Citation2009, Burghardt et al. Citation2011, Kanellopoulos et al. Citation2011). Migration of staples was reported in several of these studies. Both techniques induce hind limb varus angulation after hemiepiphysiodesis of the medial proximal tibia, but the results have been conflicting regarding whether stapling or tension-band plating is the most efficient treatment.

A limitation of our study was the small number of children included, but it was designed to test the results published in the first report on tension-band plating (Stevens, Citation2007). For both the stapling and tension-band plating groups, the 95% confidence intervals were broad (); extrapolation of the results to the overall population of children with IGV is uncertain. Larger studies can be conducted, but if smaller differences are found in larger studies they may not be of clinical significance.

MG, OR, IH, MD, MBH, and BMM designed the study. MG and OR collected the data. MG analyzed the data. MG wrote the draft manuscript. OR, IH, MD, MBH, and BMM ensured the accuracy of the data and analyses and approved the final version of the manuscript before submission.

The trial was supported by the Institute of Clinical Medicine, Aarhus University and the Central Denmark Region. No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

No competing interests declared.

- Aykut US, Yazici M, Kandemir U, Gedikoglu G, Aksoy MC, Cil A, Surat A. The effect of temporary hemiepiphyseal stapling on the growth plate: a radiologic and immunohistochemical study in rabbits. J Pediatr Orthop 2005; 25 (3): 336-41.

- Ballal MS, Bruce CE, Nayagam S. Correcting genu varum and genu valgum in children by guided growth: Temporary hemiepiphysiodesis using tension band plates. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010; 92 (2): 273-6.

- Blount WP, Clarke GR. Control of bone growth by epiphyseal stapling; a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1949; 31 (3): 464-78.

- Burghardt RD, Herzenberg JE. Temporary hemiepiphysiodesis with the eight-Plate for angular deformities: mid-term results. J Orthop Sci 2010; 15 (5): 699-704.

- Burghardt RD, Herzenberg JE, Standard SC, Paley D. Temporary hemiepiphyseal arrest using a screw and plate device to treat knee and ankle deformities in children: a preliminary report. J Child Orthop 2008; (2): 187-97.

- Burghardt RD, Specht SC, Herzenberg JE. Mechanical Failures of eight-Plate Guided Growth System for Temporary Hemiepiphysiodesis. J Pediatr Orthop 2010; 30 (6): 594-7.

- Burghardt RD, Kanellopoulos AD, Herzenberg JE. Hemiepiphyseal arrest in a porcine model. J Pediatr Orthop 2011; 31 (4): e25-e29.

- Courvoisier A, Eid A, Merloz P. Epiphyseal stapling of the proximal tibia for idiopathic genu valgum. J Child Orthop 2009; 3(3): 217-21

- Frantz CH. Epiphyseal stapling: a comprehensive review. Clin Orthop 1971; 77: 149-57.

- Fraser RK, Dickens DR, Cole WG. Medial physeal stapling for primary and secondary genu valgum in late childhood and adolescence. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1995; 77 (5): 733-5.

- Goyeneche RA, Primomo CE, Lambert N, Miscione H. Correction of bone angular deformities: experimental analysis of staples versus 8-plate. J Pediatr Orthop 2009; 29 (7): 736-40.

- Jelinek EM, Bittersohl B, Martiny F, Scharfstadt A, Krauspe R, Westhoff B. The 8-plate versus physeal stapling for temporary hemiepiphyseodesis correcting genu valgum and genu varum: a retrospective analysis of thirty five patients. Int Orthop 2012; 36 (3): 599-605.

- Kanellopoulos AD, Mavrogenis AF, Dovris D, Vlasis K, Burghart R, Soucacos PN, Papagelopoulos PJ, Herzenberg JE. Temporary hemiepiphysiodesis with blount staples and eight-plates in pigs. Orthopedics 2011; 34 (4).

- Mast N, Brown NA, Brown C, Stevens PM. Validation of a genu valgum model in a rabbit hind limb. J Pediatr Orthop 2008; 28 (3): 375-80.

- McNeely JK, Trentadue NC. Comparison of patient-controlled analgesia with and without nighttime morphine infusion following lower extremity surgery in children. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997; 13 (5): 268-73.

- Mielke CH, Stevens PM. Hemiepiphyseal stapling for knee deformities in children younger than 10 years: a preliminary report. J Pediatr Orthop 1996; 16 (4): 423-9.

- Niethard M, Deja M, Rogalski M. Correction of angular deformity of the knee in growing children by temporary hemiepiphyseodesis using the eight-plate. Z Orthop Unfall 2010; 148 (2): 215-21.

- Paley D, Tetsworth K. Mechanical axis deviation of the lower limbs. Preoperative planning of uniapical angular deformities of the tibia or femur. Clin Orthop 1992; (280): 48-64.

- Schroerlucke S, Bertrand S, Clapp J, Bundy J, Gregg FO. Failure of Orthofix eight-Plate for the Treatment of Blount Disease. J Pediatr Orthop 2009; 29 (1): 57-60.

- Stevens P. Guided growth. 1933 the present. Strategies in Trauma and Limb Reconstruction 2006; 1 (1): 29-35.

- Stevens PM. Guided growth for angular correction: a preliminary series using a tension band plate. J Pediatr Orthop 2007; 27 (3): 253-9.

- Stevens PM, Maguire M, Dales MD, Robins AJ. Physeal stapling for idiopathic genu valgum. J Pediatr Orthop 1999; 19 (5): 645-9.

- Wiemann JM, Tryon C, Szalay EA. Physeal stapling versus 8-plate hemiepiphysiodesis for guided correction of angular deformity about the knee. J Pediatr Orthop 2009; 29 (5): 481-5.

- Zuege RC, Kempken TG, Blount WP. Epiphyseal stapling for angular deformity at the knee. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1979; 61 (3): 320-9.