Abstract

Background Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered to be a valuable tool for the diagnosis of rotator cuff tears in patients with severe glenohumeral osteoarthritis who are indicated for total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA). We determined the sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value of MRI in diagnosing rotator cuff tears in such patients.

Methods MRI reports of 100 patients who had completed a shoulder MRI prior to TSA were reviewed to determine the radiologists’ interpretation of the MRI including the diagnosis, presence of a full-thickness cuff tear, and the presence of atrophy and/or fatty infiltration within the rotator cuff muscle bellies. Operative reports were used as a gold standard to determine whether a full-thickness rotator cuff tear was present.

Results Preoperative MRI reports noted 33 of the 100 patients as having a full-thickness rotator cuff tear, 17 of which had multiple tendon tears. 2 of the 33 patients with full tears on MRI were found to have full-thickness tears at surgery. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value for MRI detection of full-thickness tears were 100%, 68%, and 6% respectively, with a false-positive rate of 32% and an accuracy of 69%.

Interpretation The study suggests that although MRI is highly sensitive, it has a low positive predictive value and moderately low specificity and accuracy in detecting full-thickness rotator cuff tears in patients with severe glenohumeral osteoarthritis.

Rotator cuff status is critical for decision-making in shoulder arthroplasty (Neer et al. Citation1982, Cofield Citation1984, Barrett et al. Citation1987, Sperling et al. Citation1998, Edwards et al. Citation2002, Waldt et al. Citation2007). A reliable physical examination of the rotator cuff in the setting of glenohumeral osteoarthritis (OA) can be difficult due to pain and stiffness (Dinnes et al. Citation2003, Gupta et al. Citation2004, Komaat et al. 2005, Roemer et al. Citation2009). Accurate imaging is therefore necessary to determine the integrity of the rotator cuff when choosing between standard total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) and reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is commonly used to evaluate rotator cuff integrity, and it can also be used to evaluate glenoid morphology before shoulder arthroplasty (Karzel and Snyder Citation1993, Wang et al. Citation1994, Wnorowski et al. Citation1997, Seibold et al. Citation1999). The sensitivity and specificity of MRI for detecting full-thickness rotator cuff tears exceeds 90% in non-arthritic shoulders (Iannotti et al. Citation1991, Wang et al. Citation1994, Balich et al. Citation1997, Waldt et al. Citation2007, DeJesus et al. Citation2009). However, the sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value of this test may be different in the arthritic shoulder (Gupta et al. Citation2004, Roemer et al. Citation2009). In rheumatoid patients, one study found limited usefulness of MRI in preoperative evaluation of the rotator cuff in patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty, with an accuracy of only 71% (Soini et al. Citation2004). It has been our experience that radiologists’ interpretations of MRI in the setting of glenohumeral osteoarthritis frequently involve full-thickness rotator cuff tears not seen at the time of surgery. We retrospectively compared preoperative MRI evaluation of the rotator cuff to intraoperative findings in 100 consecutive patients. Our hypothesis was that MRI-based interpretation of full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff in osteoarthritic shoulders would have lower specificity and positive predictive value than in previously published reports.

Patients and methods

Patients

We retrospectively identified and reviewed all patients who underwent primary total shoulder arthroplasty at our institution between June 2006 and March 2010. The surgical records were reviewed by 3 of the authors. Patient permission was granted by telephone after approval of the study by our Institutional Review Board (ORA 08111901-IRB02). 100 consecutive cases were retrospectively evaluated (mean age 65 (29–90) years, 51 women). Inclusion criteria were: (1) primary total shoulder arthroplasty performed as stated in the surgical record, (2) preoperative MRI performed at the authors’ or outside institutions, (3) preoperative and pre-MRI diagnosis of glenohumeral osteoarthritis, and (4) no record of shoulder procedures between the date of the MRI and the joint replacement surgery. Patients with inflammatory or septic arthritis were not included. 4 surgeons performed all procedures. The mean time between MRI and total shoulder arthroplasty was 7 (0.5–21) months. Several outliers were noted, such that the median time interval was 5 months.

Imaging

As our purpose was to evaluate radiologist interpretation of full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff, MRI reports—rather than author interpretation of the actual images—were reviewed to determine the radiologist’s interpretation of the MRI with regard to the presence of a full-thickness tear of the rotator cuff tear. The location of the MRI was not standardized, so the scans were performed at facilities throughout the United States and the image interpretations were conducted by radiologists affiliated with each institution. Similarly, the specifications of the MRI scanners were not standardized. Finally, we had no knowledge of subspecialty or fellowship training in musculoskeletal radiology of the radiologists who did the interpretation.

Surgical intervention and examination

The rotator cuff was evaluated by the surgeon at the time of surgery. In particular, the presence of a full-thickness rotator cuff tear was noted. Operative reports did not account for the presence of partial tears, the size of the tear, or the level of retraction. However, in all patients with tears, the defects were felt to be small enough to proceed with a total shoulder arthroplasty rather than a reverse shoulder arthroplasty. A comparison was then performed between the findings of the MRI report and the surgical record of each patient.

Statistics

Intraoperative reports were used as the reference when calculating test performance. Sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, negative and positive predictive values, and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) using Wilson’s score interval were calculated for the ability of MRI to detect full-thickness rotator cuff tears. If not otherwise stated, data are presented as mean (range).

Results

MRI findings

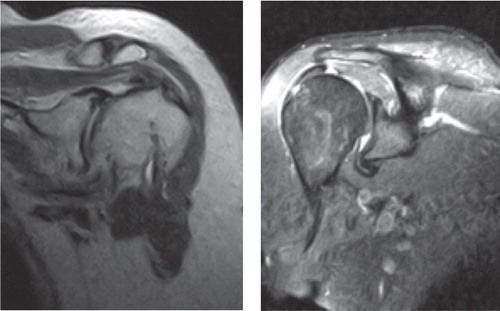

MRI findings as reported by the interpreting radiologists were that 33 patients had full-thickness tears, and 17 of them had multiple tendon tears (supraspinatus = 32, infraspinatus = 18, teres minor = 1, and subscapularis = 5). Retraction was reported in 11 cuffs (supraspinatus = 11, infraspinatus = 8, teres minor = 0, and subscapularis = 1). Atrophy of the rotator cuff was reported in 27 patients (supraspinatus = 24, infraspinatus = 18, teres minor = 8, and subscapularis = 9) and fatty infiltration in 7 patients (supraspinatus = 6, infraspinatus = 6, teres minor = 1, and subscapularis = 2). For all false-positive interpretations of full-thickness tears (n = 31), joint effusion was reported in 24 of the 31 cases. In contrast, joint effusion was present in only 35 of 67 true-negative interpretations. Examples of the false-positive cases are given in the Figure.

At surgery, 2 of the 100 patients had full-thickness rotator cuff tears. Both of the tears involved the supraspinatus tendon only.

Of the 100 cases, there were 2 true-positive, 67 true-negative, 31 false-positive, and 0 false-negative MRI readings. Sensitivity of MRI was 100% (CI: 0.96–1.0) and specificity was 68% (CI: 0.58–0.76). Positive predictive value was 6% (CI: 0.03–0.13) and negative predictive value was 100% (CI: 0.963–1.00). Accuracy was 69% (CI: 0.59–0.77).

Discussion

Our findings confirm our experience in the setting of glenohumeral osteoarthritis that radiologists’ MRI interpretation of the rotator cuff overestimates the presence of full-thickness tears. In particular, the specificity, accuracy, and positive predictive value were lower than in previously published reports.

Several authors have reported excellent MRI detection of full-thickness rotator cuff tears, with sensitivity and specificity both above 90% (Iannotti et al. Citation1991, Wang et al. Citation1994, Balich et al. Citation1997, Waldt et al. Citation2007, DeJesus et al. Citation2009). However, in the setting of glenohumeral OA, it is likely that the significant pathological and anatomical changes contribute to the high false-positive interpretation of full-thickness rotator cuff tears on preoperative MRI by radiologists (Soini et al. Citation2004). Specifically, the presence of humeral head osteophytes, joint effusion, and rotator cuff degeneration and thinning probably make evaluation of the integrity of the rotator cuff difficult (Gupta et al. Citation2004, Soini et al. Citation2004, Roemer et al. Citation2009).

These findings are comparable to those in a similar study in rheumatoid arthritis patients in which the authors found an almost identical degree of accuracy (71% as opposed to 69% in the present study) (Soini et al. Citation2004). Like osteoarthritis, rheumatoid disease also results in significant pathological change in both the glenohumeral joint and the rotator cuff, which probably complicates MRI interpretation. Furthermore, our findings are in line with a previous report on the incidence of full-thickness rotator cuff tears in the setting of glenohumeral osteoarthritis; Edwards et al. (Citation2002) found a prevalence of only 8% in 541 patients undergoing total shoulder arthroplasty. The prevalence of rotator cuff tears in the asymptomatic general population has been reported to be 20–25% (Cofield Citation1984, Ozaki et al. Citation1988, Gartsman and Milne Citation1995, Barr Citation2004, Yamaguchi et al. Citation2006). It is important to note that we only looked at radiologists’ official reports and we did not look at the treating surgeons’ interpretation of the MRI examinations. This interpretation may certainly have been different. However, many surgeons mainly rely on the MRI examinations for decision-making, so our findings are of practical importance.

Most authors evaluating test performance have reported the optimal performance of the test, with 1 or 2 musculoskeletal radiologists unblinded to the fact they were participating in a study. In contrast, MRI scans in our patients were not independently evaluated by musculoskeletal radiologists. This may be regarded as a weakness of the study and we cannot therefore be firm about stating that the interpretation was inaccurate. Rather, our findings may reflect the average clinical performance of MRI in detecting rotator cuff tears.

Additional weakness were that we did not examine partial tears intraoperatively and therefore considered partial tears to be intact rotator cuffs on MRI. However, decision-making in shoulder arthroplasty is influenced by the presence of full-thickness tears, not partial tears. We do not have information about the MRI magnet strength. Lastly, the study was retrospective.

Future studies should attempt to compare the performance of the test itself—through interpretations by independent musculoskeletal radiologists on 1.5 Tesla magnets (or greater)—to the formal reports given by radiologists, in order to show a difference between the academic and practical use of MRI. In addition, there have not yet been any investigations of the accuracy of alternative imaging modalities such as computed tomography arthrograms or ultrasound.

In conclusion, our study suggests that the accuracy of MRI in detecting full-thickness rotator cuff tears in patients with glenohumeral OA is less than in non-arthritic patients. In particular, MRI appears to be a highly sensitive test, but only moderately specific. This information will be important for clinicians—both for preoperative planning and for informed decision-making discussions with patients.

RS: data collection and writing of abstract, methods and results, statistics, and figure legend. CM, SS: writing of introduction and discussion, and editing. KM, IRB: data collection and editing. AR, NV: study proposal and editing of manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

- Balich SM, Sheley RC, Brown TR, Sauser DD, Quinn SF. MR imaging of the rotator cuff tendon: interobserver agreement and analysis of interpretive errors. Radiology 1997; 204 (1): 191-4.

- Barr KP . Rotator cuff disease. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2004; 15 (2): 475-91.

- Barrett WP, Franklin JL, Jackins SE, Wyss CR, Matsen F A 3rd. Total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1987; 69 (6): 865-72.

- Boenisch U, Lembcke O, Naumann T. Classification, clinical findings and operative treatment of degenerative and posttraumatic shoulder disease: what do we really need to know from an imaging report to establish a treatment strategy? Eur J Radiol 2000; 35 (2): 103-18.

- Cofield RH. Total shoulder arthroplasty with the Neer prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1984; 66 (6): 899-906.

- De Jesus JO, Parker L, Frangos AJ, Nazarian LN. Accuracy of MRI, MR arthrography, and ultrasound in the diagnosis of rotator cuff tears: a meta-analysis. Am J Roentgenol 2009; 192 (6): 1701-7.

- Dinnes J, Loveman E, McIntyre L, Waugh N. The effectiveness of diagnostic tests for the assessment of shoulder pain due to soft tissue disorders: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2003; 7 (29): iii,1-166.

- Edwards TB, Boulahia A, Kempf JF, Boileau P, Nemoz C, Walch G. The influence of rotator cuff disease on the results of shoulder arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis: results of a multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2002; 84 (12): 2240-8.

- Gartsman GM, Milne JC. Articular surface partial-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elb Surg 1995; 4 (6): 409-15.

- Gupta KB, Duryea J, Weissman BN. Radiographic evaluation of osteoarthritis. Radiol Clin N Am 2004; 42 (1): 11-41,v.

- Iannotti JP, Zlatkin MB, Esterhai JL, Kressel HY, Dalinka MK, Spindler KP. Magnetic resonance imaging of the shoulder. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1991; 73 (1): 17-29.

- Karzel RP, Snyder SJ. Magnetic resonance arthrography of the shoulder. A new technique of shoulder imaging. Clin Sport Med 1993; 12 (1): 123-36.

- Kornaat PR, Ceulemans RY, Kroon HM, Riyazi N, Kloppenburg M, Carter WO, Woodworth TG, Bloem JL. MRI assessment of knee osteoarthritis: Knee Osteoarthritis Scoring System (KOSS)–inter-observer and intra-observer reproducibility of a compartment-based scoring system Skeletal Radiol 2005; 34 (2): 95-102.

- Neer CS, 2nd, Watson KC, Stanton FJ. Recent experience in total shoulder replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1982; 64 (3): 319-37.

- Ozaki J, Fujimoto S, Nakagawa Y, Masuhara K, Tamai S. Tears of the rotator cuff of the shoulder associated with pathological changes in the acromion. A study in cadavera. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1988; 70 (8): 1224-30.

- Roemer FW, Eckstein F, Guermazi A. Magnetic resonance imaging-based semiquantitative and quantitative assessment in osteoarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin N Am 2009; 35 (3): 521-55.

- Seibold CJ, Mallisee TA, Erickson SJ, Boynton MD, Raasch WG, Timins ME. Rotator cuff: evaluation with US and MR imaging. Radiographics 1999; 19 (3): 685-705.

- Soini I, Belt EA, Niemitukia L, Mäenpää HM, Kautiainen HJ. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Rotator Cuff in Destroyed Rheumatoid Shoulder: Comparison with Findings during Shoulder Replacement. Acta Radiol 2004; 45 (4): 434-9.

- Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Neer hemiarthroplasty and Neer total shoulder arthroplasty in patients fifty years old or less. Long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1998; 80 (4): 464-73.

- Waldt S, Bruegel M, Mueller D, Holzapfel K, Imhoff AB, Rummeny EJ, Woertler K. patients with arthroscopic correlation. Eur Radiol 2007; 17 (2): 491-8.

- Wang YM, Shih TT, Jiang CC, Su CT, Huang KM, Hang YS, Liu TK. Magnetic resonance imaging of rotator cuff lesions. J Formos Med Asso 1994; 93 (3): 234-9.

- Wnorowski DC, Levinsohn EM, Chamberlain BC, McAndrew DL. Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of the rotator cuff: is it really accurate? Arthroscopy 1997; 13 (6): 710-9.

- Yamaguchi K, Ditsios K, Middleton WD, Hildebolt CF, Galatz LM, Teefey SA. The demographic and morphological features of rotator cuff disease. A comparison of asymptomatic and symptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006; 88 (8): 1699-704.