Abstract

Background and purpose — The pathophysiology behind bisphosphonate-associated atypical femoral fractures remains unclear. Histological findings at the fracture site itself may provide clues.

Patients and methods — Between 2008 and 2013, we collected bone biopsies including the fracture line from 4 complete and 4 incomplete atypical femoral fractures. 7 female patients reported continuous bisphosphonate use for 10 years on average. 1 patient was a man who was not using bisphosphonates. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry of the hip and spine showed no osteoporosis in 6 cases. The bone biopsies were evaluated by micro-computed tomography, infrared spectroscopy, and qualitative histology.

Results — Incomplete fractures involved the whole cortical thickness and showed a continuous gap with a mean width of 180 µm. The gap contained amorphous material and was devoid of living cells. In contrast, the adjacent bone contained living cells, including active osteoclasts. The fracture surfaces sometimes consisted of woven bone, which may have formed in localized defects caused by surface fragmentation or resorption.

Interpretation — Atypical femoral fractures show signs of attempted healing at the fracture site. The narrow width of the fracture gap and its necrotic contents are compatible with the idea that micromotion prevents healing because it leads to strains within the fracture gap that preclude cell survival.

Atypical femoral shaft fractures are a rare type of stress fracture. They have gained attention recently because of their increasing incidence and strong association with bisphosphonate treatment (Schilcher and Aspenberg Citation2009, Bauer Citation2012, Dell et al. Citation2012, Shane et al. 2013). Bisphosphonates inhibit osteoclast activity and suppress bone turnover (Russell et al. Citation2007). This has been suggested to increase the risk of stress fracture, because reduced remodeling causes an increase in bone mineral density and matrix homogeneity (Boskey et al. Citation2008), which can lead to a greater propensity for formation and propagation of cracks. A high mineral-to-matrix ratio makes the bone brittle, with increased susceptibility to microdamage. In addition, bisphosphonates appear to cause an increase in advanced glycation end-products of the extracellular bone matrix (Saito et al. Citation2008), deteriorating the mechanical properties further. These changes combined with the high mechanical stresses at the femoral shaft could lead to an increase in local microdamage, in turn leading to fracture (Mashiba et al. Citation2001).

In spite of these observations it remains unclear whether the reported changes in bone composition substantially contribute to the pathophysiology of atypical femoral fractures. An alternative or additional pathophysiological mechanism might be based on a reduced ability to heal microdamage. Microdamage usually occurs in bone (Norman and Wang Citation1997). It is taken care of by targeted remodeling: damaged areas are specifically resorbed and replaced. When bisphosphonates reduce the ability to remodel these areas, microdamage accumulates. This can progress to the formation of larger cracks, i.e. stress fractures.

We have previously described the histological picture of a bisphosphonate-associated atypical femoral fracture and found indicators suggesting impaired healing of the crack, in spite of increased remodeling of the adjacent bone (Aspenberg et al. Citation2010). In the current study, we wanted to verify those early findings. We also made new observations that were compatible with the idea that the mechanical environment in the fracture gap plays a key role in the pathophysiology.

Patients and methods

Patients with complete or incomplete atypical femoral fractures who were treated at our institution between 2008 and 2013 were recruited to the study. The study was approved by the regional ethics committee (DNR M14-09 and DNR 2011/358-31) and all the patients formally agreed to participate in the study.

Atypical femoral fractures were defined according to radiographic criteria previously described by our group (Schilcher et al. Citation2013): a transverse fracture line of the lateral femoral cortex below the lesser trochanter and above the supracondylar flare. Focal cortical thickening (callus reaction) was compulsory, while a medial spike was not. All patients reported prodromal thigh pain and a low-energy trauma but no previous trauma to the same femur. A full history of current and previous medical conditions and drug treatment was obtained through personal interviews and, when necessary, this was complemented with information from drug charts and medical records (). Bisphosphonate treatment was discontinued at admission. Patients were followed with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scanning and sequential plain radiographs were obtained or computed tomography (CT) was performed until radiographic healing.

Table 1. Background information on study cases

7 of the 8 patients were women. The male patient had never received bisphosphonates. All the female patients had been on bisphosphonate treatment for a mean period of 10 (4–21) years prior to fracture. One patient (case 6) had stopped taking bisphosphonate at the time of diagnosis, but was not operated until 1.5 years later. All the others were operated on within a few weeks. The median age of the women was 77 (57–84) years and the man was 78 years at the time of surgery. 1 patient showed multiple locations with focal cortical thickening (Mohan et al. Citation2012) in the ipsilateral femur (case 7) and 1 patient (case 1) had bilateral fractures.

Surgery

All patients had surgical fixation, either due to complete or impending fractures. 6 patients were treated with intramedullary nailing. 1 patient was treated with a locking compression plate because of a curved femur and 1 patient was treated with a dynamic hip screw. A 5-cm skin incision was made at the fracture site. 2-mm drill holes were made around the focal cortical thickening. The full-thickness cortical biopsy was then excised with a chisel. The diameter of the biopsies ranged from 8 to 15 mm. Bone biopsies were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and stored in 70% alcohol.

Clinical outcome

All fractures healed clinically. In 2 cases, the intramedullary nail was dynamized by removal of the distal locking screws (cases 3 and 4). Case 4 showed a bridging callus after a total of 6 months. Case 3 showed no bridging callus after 11 months. The patient was then given teriparatide for 3 months and the fracture healed after an additional 4 months. The 2 remaining complete fractures had healed after 4 months.

Radiology

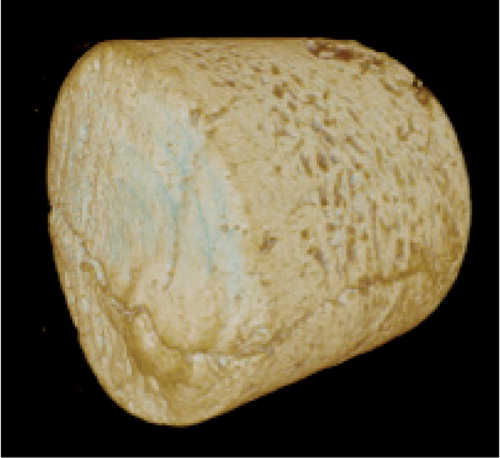

3D computational radiographs were obtained on a SkyScan1174 micro-CT (Bruker-microCT, Kontich, Belgium) to identify the fracture line. All scans were done at 180 degrees with a voltage of 50 kV and a 1-mm aluminum filter. The pixel size ranged from 8 to 24 µm. Reconstruction was done with NRecon software (Skyscan); beam hardening and ring artifact reduction was applied. For the incomplete fractures, the 3D images were used to plan sectioning of the biopsy parallel to the longitudinal axis of the bone with an Exact saw.

Histology

Samples from cases 6 and 8 were embedded undecalcified in polymethyl methacrylate. All other samples were decalcified and embedded in paraffin.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed in all cases according to institutional protocols. Anti-TRAP (tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase) antibody staining or anti-cathepsin K antibody staining was used in 3 cases where osteoclasts were difficult to identify with hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Laboratory parameters

Blood was collected for analysis of the following parameters within 48 h of surgery according to local standardized protocols: calcium, parathyroid hormone (PTH), creatinine, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), thyroid stimulation hormone (TSH), thyroxin (T3 or T4), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 25-hydroxy vitamin D, C-terminal telopeptide (CTX), osteocalcin, and serum type 1 procollagen (P1NP).

Bone composition

The bone composition was assessed by Fourier-transformed infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy from decalcified and undecalcified biopsies (cases 2 and 8, respectively), using a Hyperion 3000 microscope and a Bruker IFS66/v FTIR spectrometer with a focal plane array (FPA) detector. Measurements were conducted in transmission mode on 3-µm sections using a spectral resolution of 4 cm-1 and 64 repeated scans with a spatial resolution of 2.66 µm. Areal measurements (0.6 mm2) of the fracture gap and immediate surroundings were conducted. Pre-processing and analysis followed established protocols (Isaksson et al. 2010). The amide I peak (1585–1720 cm-1) and the phosphate peak (900–1200 cm-1) were analyzed as measures of the organic composition and mineral composition, respectively. The mineral-to-matrix ratio (phosphate/amide I) was calculated as an estimate of the degree of mineralization (Boskey et al. Citation2008). Additionally, collagen maturity (Paschalis et al. 2001), crystallinity, and acid phosphate substitution were estimated (Spevak et al. 2013).

Results

Radiology

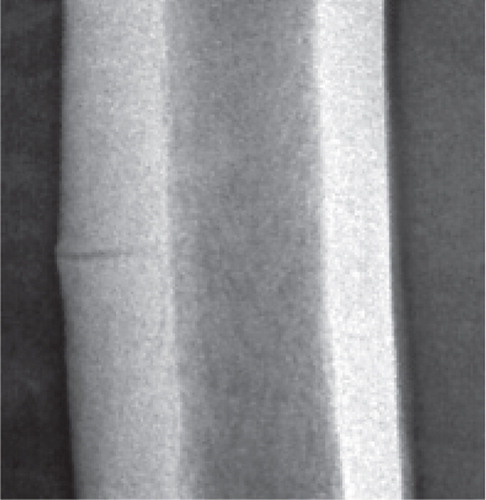

All incomplete fractures showed a radiolucent line extending through the whole thickness of the cortex (). The male patient with no bisphosphonate treatment showed radiolucent branches from the horizontal fracture line, extending proximally and distally within the subtrochanteric lateral femoral cortex. This pattern was unique for this patient.

Figure 1. Undisplaced, atypical mid-shaft fracture of the right femur. A thin fracture line extends through the whole thickness of the lateral cortex. Note the subtle callus reaction.

Micro-CT of biopsies from incomplete fractures (; cases 1, 6, and 8) showed that the contents of the fracture gap had a radio density similar to that of soft tissue, but there were patchy areas of higher density, suggesting mineral content. The proximal and distal fracture surfaces appeared to fit together, but there were some defects in the surfaces that looked like resorption cavities (). There were no regular bands as in stress fractures in metal.

Histology

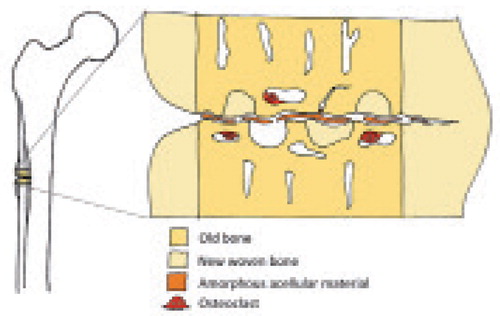

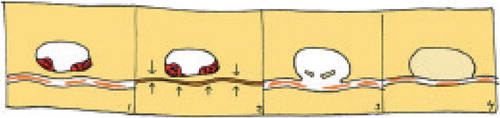

The histological findings are summarized in Table 2 (see Supplementary data) and are schematically illustrated in .

Figure 3. Schematic view of histology, showing necrotic material in the gap, resorption near the gap, and areas of new woven bone. Periosteal callus to the left.

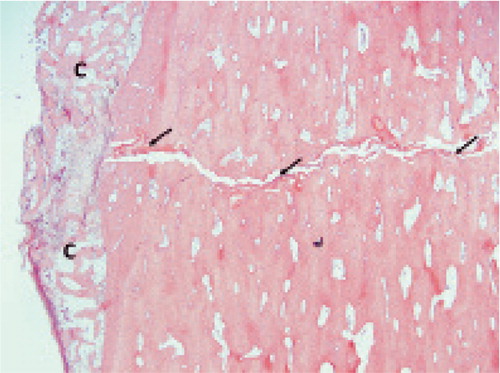

A thin fracture gap containing amorphous, acellular material. All incomplete fractures showed a fracture gap with a width of 180 (150–200) µm (). Some samples showed branching of the fracture line into the surrounding bone. The predominant finding in all incomplete samples was that the gap contained an amorphous, non-mineralized material with no discernable cells, most probably protein precipitate and detritus. In spite of the fact that the crack was surrounded by living bone, this amorphous material was not invaded, not even by inflammatory cells. Fragments of lamellar or woven bone could be found breaking off from the fracture surface. These fragments showed different degrees of degradation ranging from intact lamellar bone to mineralized remnants with a diffuse structure.

Figure 4. Opposing fracture surfaces appear to fit into each other like a foot and footprint. Oblique arrows show amorphous material in the fracture gap. C shows periosteal callus.

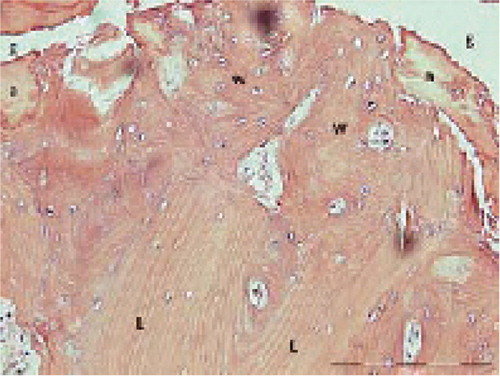

New-formed woven bone adjacent to the fracture line. The bone close to the fracture gap showed signs of recent remodeling: the osteons were interrupted by new woven bone bordering the fracture gap (). In cases 1 and 2, small areas of cartilage were seen inside the cortical bone, adjacent to the fracture.

Figure 5. Fracture gap (g) with amorphous material (a) and newly formed woven bone (w) that has replaced old lamellar bone (L).

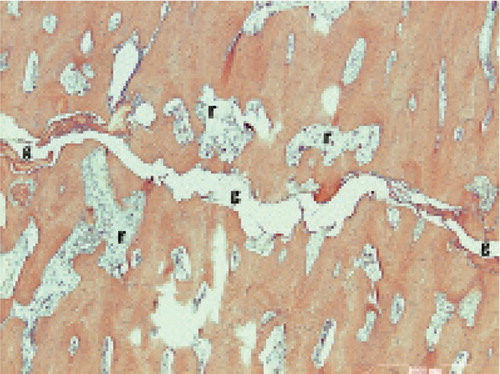

Osteoclasts. Osteoclasts were frequently found close to the fracture line and less frequently further away, except in cases 3, 5, and 7, where there were few osteoclasts—although they could be identified with anti-TRAP or anti-cathepsin K antibody staining. Giant osteoclasts—typical for bisphosphonate users (Weinstein et al. Citation2009)—were common in cases 1, 2, 4, and 6, mainly close to the fracture line. Resorption cavities in the cortex were common (). Adjacent to the fracture, they were smaller and tended to be oriented parallel to the fracture plane, while farther away from the fracture they were larger and tended to be oriented perpendicular to the fracture line.

Figure 6. Resorptive cavities (r) with increased cellular activity and numerous osteoclasts in the bone adjacent to the fracture gap (g).

Callus. All samples showed a callus reaction on both the endosteal and the periosteal aspect of the fracture. The callus consisted mainly of woven bone and soft tissue. The periosteal bony callus was interrupted where the fracture reached the periosteal surface. Corresponding to this site, there was only soft tissue, and the callus formation is therefore unlikely to have provided mechanical stability.

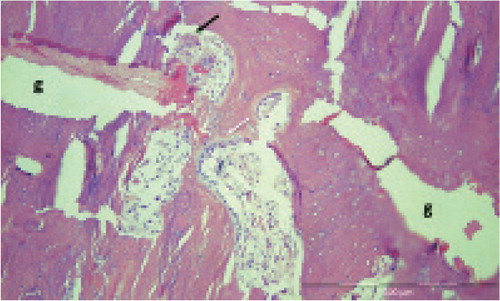

Slow gap-bridging after 1.5 years. Case 6 was the patient who stopped taking bisphosphonates at diagnosis, 1.5 years before surgery. Still, she had pain on weight bearing. In her case, both the endosteal and periosteal callus appeared to be continuous, connecting the proximal and distal fragments. This patient also showed occasional remodeling units within the fracture; these bridged the whole width of the gap (). She reported immediate pain relief after biopsy and stabilization. Remodeling within the fracture gap could not be seen in any of the other patients.

Figure 7. Remodeling bridging the fracture gap (g) in case 6. Black arrow: osteoclast. White arrow: osteoblasts.

Areas with dead osteocytes. Areas with empty osteocyte lacunae were found, mainly at a distance from the fracture line, in cases 1, 3, 5, and 7. Three of these cases reported some of the longest durations of bisphosphonate use (6, 16, and 13 years, respectively).

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and blood parameters

Only 2 patients had osteoporosis according to DEXA criteria: 1 with a lumbar T-score of –3.5 (hip –1.1) and the other with a hip T-score of –3.0 (lumbar –1.3). Hip T-scores were above –0.2 in the remaining patients, i.e. they had neither osteopenia nor osteoporosis ().

CTX values ranged from 65 to 463 ng/L (Table 3, see Supplementary data). Cases 5 and 7 showed very low CTX values of 65 and 75 ng/L, respectively. These patients had T-scores within the osteopenic or normal range. 25-hydroxy vitamin D values were below the reference levels in all cases where this parameter was available. The male patient had a very low vitamin D level, along with elevated PTH levels and increased P1NP (Table 3, see Supplementary data).

Bone composition

The mineral-to-matrix ratio was close to 0 in the amorphous material in the fracture, whereas it ranged from 3 to 5 in the surrounding bone. This was due to high amounts of organic matrix (amide I absorption) without much mineral (phosphate) in the amorphous material (Figure 8, see Supplementary data). The increased acid phosphate parameter in the fracture region indicated increased remodeling activity or younger tissue in these regions.

Discussion

We found that atypical femoral fractures appear to consist of a crack, meandering through the lateral cortex with its main direction perpendicular to the long axis of the bone. The crack is thin and mainly contains amorphous acellular material, and some traces of bony fragments. The surrounding bone shows signs of remodeling, mainly represented by the presence of osteoclasts, resorption cavities, and woven bone facing the crack. It was striking that there were no signs of remodeling or callus formation within the fracture gap itself, despite the cellular activity in the adjacent tissue. These findings are compatible with the idea that normal gait produces strains in the fracture gap that are too large for cell survival. The patient who stopped taking bisphosphonate 1.5 years before surgery still had an open crack, but in her case the endosteal and periosteal callus may have stabilized the fracture sufficiently for direct fracture healing to begin.

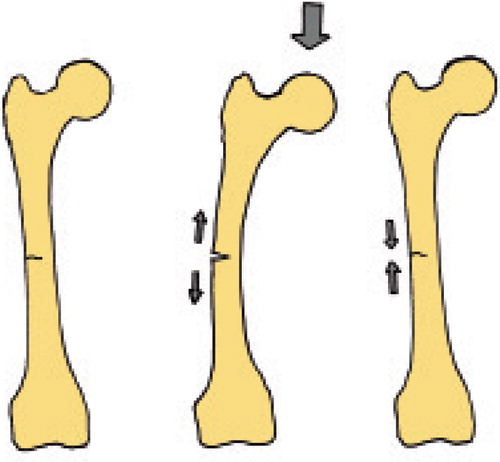

According to the theory of interfragmentary strain and tissue differentiation, the strain in a fracture gap influences the tissue differentiation pathways (Perren Citation1979). Because the cracks in our patients were so thin, even a moderate deformation of the entire femur due to loading could be expected to cause strains in the gap that prevent cell survival (). We have recently shown this with a mathematical model of tibial stress fractures (Fågelberg et al., unpublished data).

Despite the remodeling adjacent to the crack, there was almost no resorption of the fracture surface itself. This is compatible with findings from a stress fracture model of the rat ulna during bisphosphonate treatment (Sloan et al. Citation2010, Kidd et al. Citation2011). In addition to mechanical reasons, the absence of fracture surface resorption in our patients could have been caused by bisphosphonate treatment. Because the fracture surfaces are not covered by cells, the mineral in these areas is more accessible to bisphosphonate than other bone surfaces. These surfaces might act as a trap for circulating bisphosphonates, making them particularly resistant to resorption. Even 1.5 years after cessation of treatment, only a few remodeling units had succeeded in bridging the gap, and these still did not provide sufficient mechanical stability to relieve pain on weight bearing.

While interfragmentary strain could explain the inability to heal the fracture once it has occurred, this does not explain why the fracture occurred in the first place. Elderly people have a higher amount of microdamage in cortical bone than younger people (Diab et al. Citation2006). Targeted remodeling is a process whereby areas with microdamage are selectively targeted by osteoclasts, resorbed, and replaced (Burr Citation2002). Ongoing bisphosphonate treatment inhibits this process, and microdamage can accumulate, allowing smaller cracks to coalesce to larger cracks and ultimately form a stress fracture.

The woven bone, sometimes seen facing the fracture gap, calls for an explanation. We saw different stages of degradation of lamellar and cellular structures at the fracture surface, and some bone fragments were obviously about to come loose from the fracture surface. This is probably related to abrasive processes within the fracture gap. Defects in the fracture surface may form where bone fragments have been detached, or where resorptive cavities have merged with the fracture gap (). These defects will be protected from the deleterious strains, due to their width, and may provide an environment in which bone healing processes can occur. This could explain the presence of woven bone around the fracture gap. Still, this does not lead to union, probably because these areas of woven bone formation at any given time are small, and therefore unable to resist the forces that occur during gait.

Figure 10. How new bone can form at the fracture surface without cells in the gap: Resorption and fragmentation create defects in the fracture surface that become filled with new bone.

Our patients were not a homogeneous group of elderly individuals, and they had different comorbidities and drug treatments, which may have influenced fracture healing. However, we have shown that patients with atypical femoral fractures do not have a higher incidence of comorbidities than other fracture patients of similar age (Schilcher et al. Citation2011). On the contrary, they appear to be younger and healthier. Strikingly, BMD values were normal in most of the patients, which is similar to findings by others (Odvina et al. Citation2005). We found normal C-terminal telopeptide (CTX) values in 4 patients and very low values in 2 patients. Whether CTX values can be used to predict atypical femoral fractures in bisphosphonate treatment remains to be determined.

The bisphosphonate-free male patient showed a similar appearance of the fracture line to that in patients with bisphosphonate use. However, there was a larger resorptive area within the cortex on radiographs and by histology. This might reflect an increased degree of remodeling due to vitamin D deficiency and secondary hyperparathyroidism, or the absence of the inhibitory effect of a bisphosphonate.

Histological analyses of atypical femoral fractures are uncommon and the findings have been inconsistent. Some authors have described the bone near the fracture, but not the fracture itself (Somford et al. Citation2009). Kajino et al. (Citation2011) investigated a biopsy from a complete fracture including the fracture surface. They found immature bone on the periosteal surface and reported that almost no TRAP-positive cells could be found. In another case, there was a bridging periosteal callus reaction, a fracture gap filled with blood, and a total absence of remodeling in the cortical bone (Ing-Lorenzini et al. Citation2009). All our patients with incomplete fractures showed numerous osteoclasts and increased remodeling in the cortical bone adjacent to the fracture. The fracture gap contained amorphic material with traces of bony fragments. FTIR could not verify that the amorphic material had mineral content, most likely due to difficulties in directing measurements to those few areas where bone fragments could be seen by histology. In 3 of our patients with complete fractures, few osteoclasts were identifiable. No conclusions can be made from differences between the subgroups, due to the small numbers. Our study was limited to a small number of cases from the Caucasian population of a Nordic country, which limits generalizability. In all the patients from whom vitamin D levels were available, the values were low. This may have affected bone metabolism.

In conclusion, our observations show that the bone at the fracture site is not inert, but that it is undergoing remodeling. The crack may be maintained by a high degree of strain locally, which prevents healing.

Supplementary data

Tables 2 and 3 and Figure 8 are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 6674.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (898.5 KB)Study design: PA and JS. Conduction of study: JS. Data collection: JS and PA. Data analysis: JS, HI, OS, and PA. PA and JS also take responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis. Interpretation of data: JS, HI, OS, and PA. Micro-CT analysis: OS. FTIR analysis: HI. Drafting of manuscript: JS and PA. Revision of manuscript: PA and JS. Approval of final version of the manuscript: PA, JS, OS, and HI.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council (VR 2009-6725), Linköping University, Östergötland County Council, and the King Gustaf V and Queen Victoria Free Mason Foundation.

PA has a patent on a process for coating metal implants with bisphosphonates, and has shares in a company that is trying to commercialize the principle (Addbio AB). PA has also received consulting reimbursement and grants from Eli Lilly and Co. These grants partly cover the salary of OS.

JS and HI have no competing interests to declare.

- Aspenberg P, Schilcher J, Fahlgren A. Histology of an undisplaced femoral fatigue fracture in association with bisphosphonate treatment. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (4): 460–2.

- Bauer DC. Atypical femoral fracture risk in patients treated with bisphosphonates. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172 (12): 936–7.

- Boskey AL, Spevak L, Weinstein RS. Spectroscopic markers of bone quality in alendronate-treated postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 2008; 20 (5): 793–800.

- Burr DB. Targeted and nontargeted remodeling. Bone 2002; 30 (1): 2–4.

- Dell RM, Adams AL, Greene DF, Funahashi TT, Silverman SL, Eisemon EO, et al. Incidence of atypical nontraumatic diaphyseal fractures of the femur. J Bone and Miner Res 2012; 27 (12): 2544–50.

- Diab T, Condon KW, Burr DB, Vashishth D. Age-related change in the damage morphology of human cortical bone and its role in bone fragility. Bone 2006; 38 (3): 427–31.

- Ing-Lorenzini K, Desmeules J, Plachta O, Suva D, Dayer P, Peter R. Low-energy femoral fractures associated with the long-term use of bisphosphonates. Drug Saf 2009; 32 (9): 775–85.

- Kajino Y, Kabata T, Watanabe K, Tsuchiya H. Histological finding of atypical subtrochanteric fracture after long-term alendronate therapy. J Orthop Sci 2011; 17 (3): 313–8.

- Kidd LJ, Cowling NR, Wu A CK, Kelly WL, Forwood MR. Bisphosphonate treatment delays stress fracture remodeling in the rat ulna. J Orthop Res 2011; 29 (12): 1827–33.

- Mashiba T, Turner CH, Hirano T, Forwood MR, Johnston CC, Burr DB. Effects of suppressed bone turnover by bisphosphonates on microdamage accumulation and biomechanical properties in clinically relevant skeletal sites in beagles. Bone 2001; 28 (5): 524–31.

- Mohan PC, Howe TS, Koh J SB, Png MA. Radiographic features of multifocal endosteal thickening of the femur in patients on long-term bisphosphonate therapy. Eur Radiol 2012; 23 (1): 222–7.

- Norman TL, Wang Z. Microdamage of human cortical bone: incidence and morphology in long bones. Bone 1997; 20 (4): 375–9.

- Odvina CV, Zerwekh JE, Rao DS, Maalouf N, Gottschalk FA, Pak C YC. Severely suppressed bone turnover: a potential complication of alendronate therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90 (3): 1294–301.

- Perren SM. Physical and biological aspects of fracture healing with special reference to internal fixation. Clin Orthop 1979; (138): 175–96.

- Russell R GG, Xia Z, Dunford JE, Oppermann U, Kwaasi A, Hulley PA, et al. Bisphosphonates: an update on mechanisms of action and how these relate to clinical efficacy. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007; 1117: 209–57.

- Saito M, Mori S, Mashiba T, Komatsubara S, Marumo K. Collagen maturity, glycation induced-pentosidine, and mineralization are increased following 3-year treatment with incadronate in dogs. Osteoporos Int 2008; 19 (9): 1343–54.

- Schilcher J, Aspenberg P. Incidence of stress fractures of the femoral shaft in women treated with bisphosphonate. Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (4): 413–5.

- Schilcher J, Michaëlsson K, Aspenberg P. Bisphosphonate Use and atypical fractures of the femoral shaft. N Engl J Med 2011; 364 (18): 1728–37.

- Schilcher J, Koeppen V, Ranstam J, Skripitz R, Michaëlsson K, Aspenberg P. Atypical femoral fractures are a separate entity, characterized by highly specific radiographic features. A comparison of 59 cases and 218 controls. Bone 2013; 52 (1): 389–92.

- Shane E, Burr D, Abrahamsen B, Adler RA, Brown TD, Cheung AM, et al. Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: Second report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res 2014; 29(1): 1-23.

- Sloan AV, Martin JR, Li S, Li J. Parathyroid hormone and bisphosphonate have opposite effects on stress fracture repair. Bone 2010; 47 (2): 235–40.

- Somford MP, Draijer FW, Thomassen BJ, Chavassieux PM, Boivin G, Papapoulos SE. Bilateral fractures of the femur diaphysis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis on long-term treatment with alendronate: Clues to the mechanism of increased bone fragility. J Bone Miner Res 2009; 24 (10): 1736–40.

- Weinstein RS, Roberson PK, Manolagas SC. Giant osteoclast formation and long-term oral bisphosphonate therapy. N Engl J Med 2009; 360 (1): 53–62.