Abstract

Background — Tibial fracture is the third most common long-bone fracture in children. Traditionally, most tibial fractures in children have been treated non-operatively, but there are no long-term results.

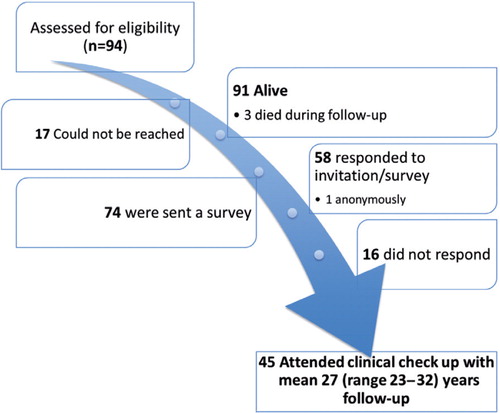

Methods — 94 children (64 boys) were treated for a tibial fracture in Aurora City Hospital during the period 1980–89 but 20 could not be included in the study. 58 of the remaining 74 patients returned a written questionnaire and 45 attended a follow-up examination at mean 27 (23–32) years after the fracture.

Results — 89 children had been treated by manipulation under anesthesia and cast-immobilization, 4 by skeletal traction, and 1 with pin fixation. 41 fractures had been re-manipulated. The mean length of hospital stay was 5 (1–26) days. Primary complications were recorded in 5 children. The childrens’ memories of treatment were positive in two-thirds of cases. The mean subjective VAS score (range 0–10) for function appearance was 9. Leg-length discrepancy (5–10 mm) was found clinically in 10 of 45 subjects and rotational deformities exceeding 20° in 4. None of the subjects walked with a limp. None had axial malalignment exceeding 10°. Osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee was seen in radiographs from 2 subjects.

Interpretation — The long-term outcome of tibial fractures in children treated non-operatively is generally good.

Tibial fractures are among the most common long-bone fractures in children (Shannak Citation1988, Landin Citation1997, Mäyränpää et al. Citation2010). Primary complications such as vascular or nerve injuries or compartment syndrome are rare. Secondary complications include malunion and premature physeal closure in fractures extending to physis.

Operative treatment has recently gained popularity, although most uncomplicated tibial fractures can be safely treated with closed reduction and cast-immobilization (Setter and Palomino Citation2006, Heinrich and Mooney Citation2010). There have been very few reports on the long-term results of tibial fracture treatment in children.

Here we present long-term outcomes in children (< 15 years of age) who were treated for a tibial fracture in Aurora City Hospital, Helsinki during the period 1980–89. Aurora City Hospital was the primary treatment center for fractures in children in Helsinki during the study period.

Patients and methods

Children aged 0–15 years who had been treated for a tibial fracture in Aurora City Hospital between 1980 and 1989 were searched for in hospital files, and 94 were found in the operation room records. Patients treated without anesthesia in the emergency department could not be included in this study because the admission records of the pediatric emergency department were no longer available. Demographic data, injury mechanism, and mode of treatment were collected from the patient files (3 were missing). The primary radiographs had been destroyed, but radiologists’ reports were still available for 14 of the 45 patients who attended the follow-up.

A questionnaire and an invitation to attend a clinical and radiographic follow-up examination was sent to 74 of these subjects (3 had died and 17 could not be reached) (). 58 answered the questionnaire, which was designed to collect memories concerning their treatment and subjective results including perceived leg-length discrepancy, angular deformities, and possible symptoms. The subjects were asked to grade the function and appearance of the injured limb using a visual analog scale (VAS; 0–10).

Figure 1. Flow chart describing the assessment and enrollment procedure for 94 individuals who had been treated for a tibial fracture in the operation room of Aurora Hospital, Helsinki, Finland during 1980–1989.

45 subjects attended a follow-up examination at mean 27 (23–32) years after the injury. Gait was observed. Leg-length discrepancy was measured using block test. Scars were identified and the circumference of both thighs and calves was measured at midpoint. Passive range of motion (ROM) of both knees, both hips, and both ankles was registered. The stability of knees and ankles was tested.

A musculoskeletal radiologist (ML) retrospectively evaluated plain radiographs obtained at the check-up in adulthood. Both injured and uninjured legs were imaged separately using a standing, weight-bearing CR radiograph obtained at a distance of 2 meters. A lateral view of the injured side was obtained at 1.15 meters, with the subject lying on the originally injured side. The mechanical axis of both lower extremities was analyzed according to Hagstedt et al. (Citation1980). The center of the femoral head was defined using Mose circles (Mose Citation1980), with midpoint of the knee in the middle of the femoral condyles at the level of the intercondylar notch and midpoint of the ankle in the middle of the superior facet of the talus, respectively. Angular deformity of the tibia was assessed (valgus/varus in the AP view of both legs, antecurvatum/recurvatum in the lateral view of the injured leg only). Angulation of the tibial diaphysis was measured by drawing a line through the mid-section of the tibial diaphysis, in both AP and lateral projections. The length of both tibias was measured from the AP views. The radiographs were also analyzed for signs of osteoarthritis according to a 3-point scale (normal = grade 0; joint space narrowing = grade 1; osteophytes, cysts, or erosions = grade 2).

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 software. The t-test was used for differences and Spearman’s rho for correlations. The level of significance was set at 5%.

The ethics committee of Helsinki University Central Hospital approved the study protocol (approval identification number 68/E7/2002).

Results

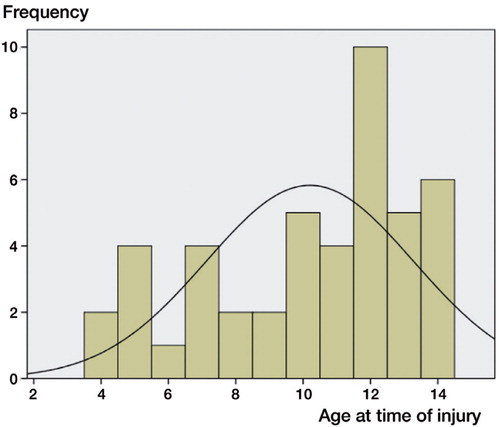

Demographic data, injury mechanism, and fracture location are shown in snd the . 89 children had been treated by manipulation under anesthesia (MUA) and cast-immobilization, 4 by calcaneal traction, and 1 with pin fixation. All 5 operatively treated children had had an open fracture. The mean length of hospital stay was 5 (1–26) days and the mean length of cast-immobilization was 59 (26–149) days. Re-manipulation of the fracture was performed in 41 children (wedging of the primary cast in the outpatient clinic: 22; re-manipulation under anesthesia: 19). All but 3 of these children had acceptable alignment in their first postoperative radiograph according to the surgeon’s and/or radiologist’s report. Of the subjects who attended the follow-up, 20 of 45 had required re-manipulation of the fracture. 4 patients had had complications related to the treatment (skin lesions: 2; osteoporosis: 1; malunion: 1). Injury-related complications occurred in only 1 subject, who developed premature closure of the distal tibial growth plate. The last routine check-up in the outpatient clinic was at mean 4 (1–22) months after the injury.

Figure 2. Age distribution at injury for patients who attended the final check as adults. The line indicates normal distribution.

Characteristics of the 94 children treated at Aurora Hospital, Helsinki, during the period 1980–1989

According to the subjects’ assessments, memories of treatment were positive in 32, negative in 6, neutral in 4, non-existent in 2, and in 8 cases they were not specified. This question was not answered in 6 cases. Intense pain was reported as the only memory by 6 patients, 1 of them remembered someone telling him “a child does not feel pain”. Functional long-term VAS result averaged 9 (6–10). 17 patients complained of a deformity, 13 of pain, 10 of leg-length discrepancy, and 3 of having a limp. The mean subjective grade for the cosmetic appearance of the injured leg was 9 (5–10).

Clinically, leg-length discrepancy was detected in 10 subjects (5 mm in 5 and 10 mm in 5). The injured limb was shorter in 6 of them. These patients were 7–12 years old at the time of the fracture (mean 12 years). None had a limp at follow-up examination. The mean foot progression angle was 10° in both legs (range 0–30°). 6 patients had difficulties in squatting for no obvious reason.

Passive ROM values for hip, knee, and ankle joints were symmetrical. The mean thigh-foot angle was 5° (0–55) for the injured limb and 3° (0–17) for the uninjured limb (p = 0.06). 4 of the 45 patients had a thigh-foot angle exceeding 19° in the injured leg. Mean calf and thigh circumferences were symmetrical, 37 (30–44) cm and 52 (42–61) cm, respectively. None of the patients had instability in either knee or either ankle joint.

Radiographic tibia-length discrepancy exceeded 10 mm in 5 subjects (median 5 (1–22) mm), one of whom had a clinically detectable leg-length discrepancy. None of these 5 subjects were aware of the discrepancy. The mean length of the tibias measured from the radiographs was 38 (31–45) cm.

The mean angulation in the coronal plane was 3° (0–10) on the injured side and 1° (0–5) on the contralateral side (p = 0.001). 4 patients had angulation exceeding 5° (3 in valgus, 1 in varus). The mean angulation in the sagittal plane was 3° (0–8) in the injured tibia. 8 subjects had angulation exceeding 5°.

2 of the 45 subjects had radiographically visible degenerative changes that could not be explained by axial malalignment or leg-length discrepancy: 1 had bilateral grade-1 osteoarthritis in the hip joints and 1 had bilateral grade-1 osteoarthritis in both the hips and the knees.

Discussion

There have been few studies reporting the long-term results of tibial fracture treatment in children. A cohort of 86 children was followed up by Swaan and Oppers (Citation1971) for mean 6 years to establish the extent to which angular deformities remodel, and to investigate whether longitudinal bone growth accelerates due to tibial fractures. They found that age at the time of injury was important: angular deformities remodeled in younger children and they also showed lengthening of the limb, whereas the remodeling was limited in older children. Hansen et al. (Citation1976) studied 102 non-operatively treated children (aged 1–15) and followed 85 of them for an average of 2 years. They concluded that a favorable prognosis and minor complications can be expected, and that angular deformities corrected by 10%—unrelated to the age of the patient. Shannak (Citation1988) reported on 117 children with an average follow-up of 4 years. There were good results after non-operative treatment: 6 patients had angular deformity >10° (up to 15° angulation corrected), and shortening of up to 10 mm was compensated by growth acceleration.

It is generally accepted that most low-energy tibial shaft fractures can be treated non-operatively, whereas open, displaced, or comminuted fractures may benefit from surgical treatment (Gordon and O’Donnell Citation2012). Numerous studies have been conducted to describe and compare different operative treatment methods for tibial fractures; flexible intramedullary nailing has been found to be effective and to have low complication rates (Qidwai Citation2001, Gordon et al. Citation2003, Citation2007, O’Brien et al. Citation2004, Goodwin et al. Citation2005, Kubiak et al. Citation2005, Srivastava et al. Citation2008, Lefaivre et al. Citation2008). To our knowledge, our study had the longest ever follow-up of tibial fractures in children.

The demographic characteristics (age, sex, and trauma mechanism) of the cases of fracture in our series are similar to those previously reported (Mashru et al. Citation2005, Setter and Palomino Citation2006). Most of our children were treated non-operatively by closed reduction and casting; 5 patients with open fractures underwent operative treatment. According to the literature, most tibial fractures in children can and should be treated non-operatively (Mashru et al. Citation2005, Setter and Palomino Citation2006, Heinrich and Mooney Citation2010). This, however, is mainly based on authors’ experience, since there have been few results reported on non-operative treatment. In our series, 41 of 94 children had angular deformities during their treatment, requiring re-manipulation or cast wedging during the first weeks of treatment. Only 3 of these children had unacceptable alignment in their first postoperative radiograph. This supports the guidelines on routine follow-up radiographs taken weekly during the first 3–4 weeks of follow-up (Heinrich and Mooney Citation2010).

Complications were rare in our series—during the initial treatment and follow-up, only 5 of 94 children had complications. Gordon et al. (Citation2003) reported a complication rate of 11/44 after external fixation. On the other hand, Qidwai (Citation2001) reported complications in only 6 of 84 patients treated with Kirschner wiring, and O’Brien et al. (Citation2004) reported a single superficial wound infection after flexible titanium nailing in 14 children. In another report by Gordon et al. (Citation2007), a high rate (5/51) of delayed union was described after titanium elastic nailing. Reports describing operative treatment methods, however, include children with more serious fractures, and thus direct comparison cannot be made. Our results suggest that non-operative treatment is safe and results in a low complication rate.

Most of our children were satisfied with their treatment and had positive memories as adults. It is noteworthy, however, that in 6 of 58 individuals the only memory of treatment was intense pain during treatment. This unfortunately reflects the practice in pediatric analgesia in the 1980s in Finland.

The subjective results for both function and appearance were high in our patients. In their self-assessment, 3 patients reported limping but there was no evidence of this in the clinical examination. The patients may experience uncertainty about their limbs due to the injury, although this cannot be verified.

In the clinical examination, none of the subjects had greater than 10 mm leg-length discrepancy and none presented with limping. Passive ROM in the lower limb joints was similar in the injured and uninjured feet. The circumferences of both thigh and calf were also similar. These findings support the idea that good results can be obtained with cast treatment. Substantial rotational deformities were found in 4 of 45 patients with a peak external tibial torsion of 55°. This is an important finding, since rotational deformities do not correct spontaneously and can be difficult to assess (Hansen et al. Citation1976). Possible rotational deformities should be carefully assessed during the treatment and follow-up.

Most leg-length discrepancies were under 10 mm; in 5 out of 45 subjects, the difference was more than 10 mm. Only 1 of these had a clinically detectable discrepancy and none of them had recognized it themselves. Harvey et al. (Citation2010) reported that limb-length inequality of >10 mm is associated with knee-joint arthritis. According to the literature, the growth acceleration often seen after femoral fractures (Palmu et al. Citation2013) is not as pronounced after tibial fractures (Shannak Citation1988, Heinrich and Mooney Citation2010). Furthermore, 30 of the 45 subjects who attended the final check had been older than 10 years at injury, when the influence of fracture on bone growth is less than in younger children (Swaan and Oppers Citation1971).

In the radiographic evaluation, the angular deformities in either coronal or sagittal planes did not exceed 10°. Almost one-half of the patients had undergone correction of angular deformities during the treatment. This again supports the guidelines on close radiographic follow-up of the injured limb during the early stages of treatment. A weakness of the present study was that we were unable to evaluate the initial radiographs.

Of the 45 subjects who attended the final check-up, 2 presented with bilateral osteoarthritis: 1 in both the hip joints and the knee joints and 1 in the hip joints only. We found no correlations between other clinical or radiographic measures and the arthritis. The fact that the degenerative changes were bilateral may indicate that these changes were independent of the fracture, contrary to our previous findings in the cases of femoral fractures (Palmu et al. Citation2013).

Intramedullary nailing (FIN) of tibial fractures in children has gained popularity. FIN allows early discharge from hospital and early mobilization, does not usually require casting, and avoids the repeated re-manipulations often needed in non-operative treatment to maintain axial alignment. On the other hand, hardware removal is recommended in FIN treatment in many institutions, which requires an additional operation.

In summary, non-operative treatment of tibial fractures in children is safe, and good long-term results can generally be expected.

SP: planning of the study design, data collection and analysis, statistical analysis, and preparation of manuscript. SA: data collection and preparation of manuscript. ML: radiographic evaluation and preparation of manuscript. RP: planning of the study design and data collection. JP: planning of the study design and preparation of manuscript. YN: planning of the study design, data analysis, and preparation of manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

- Goodwin RC, Gaynor T, Mahar A, Oka R, Lalonde FD. Intramedullary flexible nail fixation of unstable pediatric tibial diaphyseal fractures. J Pediatr Orthop 2005; 25: 570-6.

- Gordon JE, O’Donnell JC. Tibia fractures: What should be fixed? J Pediatr Orthop 2012; (32)1: S52-S61.

- Gordon JE, Schoenecker PL, Oda JE, Ortman MR, Szymanski DA, Dobbs MB, Luhmann SJ. A comparison of monolateral and circular external fixation of unstable diaphyseal tibial fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop B 2003; 12: 338-45.

- Gordon JE, Gregush RV, Schoenecker PL, Dobbs MB, Luhmann SJ. Complications after titanium elastic nailing of pediatric tibial fractures. J Pediatr Orthop 2007; 27: 442-6.

- Hagstedt B, Norman O, Olsson TH, Tjörnstrand B. Technical accuracy in high tibial osteotomy for gonarthrosis. Acta Orthop Scand 1980; 51: 963-70.

- Hansen BA, Greiff J, Bergmann F. Fractures of the tibia in children. Acta Orth Scand 1976; 47: 448-53.

- Harvey WF, Yang M, Cooke T DV, Segal NA, Lane N, Lewis CE, Felson DT. Association of leg-length inequality with knee osteoarthritis. A cohort study. Ann Int Med 2010; 152: 287-95.

- Heinrich SD, Mooney JF. Fractures of the shaft of the tibia and fibula. Chapt. 25 in: Rockwood and Wilkins’ Fractures in Children, 7th ed., Beaty and Kasser eds. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Philadelphia PA. 2010: 931-66.

- Kubiak EN, Egol KA, Scher D, Wasserman B, Feldman D, Koval KJ. Operative treatment of tibial fractures in children: Are elastic stable intramedullary nails an improvement over external fixation? J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005; 8: 1761-8.

- Landin AL. Epidemiology of children fractures. J Pediatr Orthop Part B 1997; 6: 79-83.

- Lefaivre KA, Guy P, Chan H, Blachut PA. Long-term follow-up of tibial shaft fractures treated with intramedullary nailing. J Orthop Trauma 2008; 8: 525-9.

- Mashru RP, Herman MJ, Pizzutillo PD. Tibial shaft fractures in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2005; 13: 345-352.

- Mose K. Methods of measuring in Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease with special regard to the prognosis. Clin Orthop 1980; (150): 103-9.

- Mäyränpää MK, Mäkitie O, Kallio PE. >Decreasing incidence and changing pattern of childhood fractures: A population-based study. J Bone Miner Res 2010; 25 (12): 2752-9.

- O’Brien T, Weisman DS, Ronchetti P, Piller CP, Maloney M. Flexible titanium nailing for the treatment of the unstable pediatric tibial fracture. J Pediatr Orthop 2004; 24: 601-9.

- Palmu SA, Lohman M, Paukku RT, Peltonen JI, Nietosvaara Y. Childhood femoral fracture can lead to premature knee-joint arthritis – 21-year follow-up results; a retrospective study. Acta Orthopaedica 2013; 84 (1): 71-5.

- Qidwai SA. Intramedullary Kirschner wiring for tibia fractures in children. J Ped Orthop 2001; 21: 294-7.

- Setter KJ, Palomino KE. Pediatric tibia fractures: current concepts. Curr Opin Pediatr 2006; 18: 30-5.

- Shannak AO. Tibial fractures in children: Follow-up study. J Pediatr Orthop 1988; 8: 306–10.

- Srivastava AK, Mehlman CT, Wall EJ, Do TT. Elastic stable intramedullary nailing of tibial shaft fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2008; 28: 152-8.

- Swaan JW, Oppers VM. Crural fractures in children. A study of the incidence of changes of the axial position and of enhanced longitudinal growth of the tibia after the healing of crural fractures. Arch Chir Neerl 1971; 23 (4): 259-72.