Abstract

Background — Revision arthroplasty often requires anchoring of prostheses to poor-quality or deficient bone stock. Recently, newer porous materials have been introduced onto the market as additional, and perhaps better, treatment options for revision arthroplasty. To date, there is no information on how these porous metals interface with bone cement. This is of clinical importance, since these components may require cementing to other prosthesis components and occasionally to bone.

Methods — We created porous metal and bone cylinders of the same size and geometry and cemented them in a well-established standardized setting. These were then placed under tensile loading and torsional loading until failure was achieved. This permitted comparison of the porous metal/cement interface (group A) with the well-studied bone/cement interface (group B).

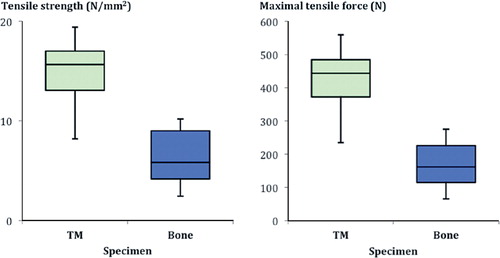

Results — The group A interface was statistically significantly stronger than the group B interface, despite having significantly reduced depth of cement penetration: it showed a larger maximum tensile force (effect size 2.7), superior maximum tensile strength (effect size 2.6), greater maximum torsional force (effect size 2.2), and higher rotational stiffness (effect size 1.5).

Interpretation — The newer porous implants showed good interface properties when cemented using medium-viscosity bone cement. The axial and rotational mechanical strength of a porous metal/cement interface appeared to be greater than the strength of the standard bone/cement interface. These results indicate that cementing of porous implants can provide great stability in situations where it is needed.

In revision joint arthroplasty, the surgeon is often confronted with deficient bone stock and must attempt to bridge bone defects when grafting is not feasible. Newer highly porous implants and materials, which allow cementless implantation, have been introduced to improve the results of revision and reconstruction of these bony defects (Levine Citation2008). These implants, made of tantalum, have higher porosity, with a reduced modulus of elasticity and a higher coefficient of friction compared to older implants—properties that are postulated to improve primary and secondary stability (Bobyn et al. Citation1999a, Levine Citation2008, Pulido et al. Citation2011). The highly porous characteristics of these new porous implants are claimed to promote more rapid and earlier osteointegration compared to older implants with roughened surfaces (Bobyn et al. Citation1999a, Pulido et al. Citation2011). They should therefore theoretically prevent or reduce micromotions and the creation of abrasion particles. Several animal experiments have been done to investigate this (Bobyn et al. Citation1999a, Citationb). Also, the highly elastic characteristics of the material are thought to reduce bone loss by stress shielding (Levine et al. Citation2006).

The predicted early osteointegration that results from the use of these components has increased their use. Augments and buttresses made of this material have been used in hip revision surgery to treat bone defects (Bobyn et al. Citation2004, Beckmann et al. Citation2014). These implants may require cement fixation between each component. Also, in knee revision surgery TM augments, wedges, and cones have been used in patients with severe bone loss (Bobyn et al. Citation2004, Meneghini et al. Citation2009, Jensen et al. Citation2012, Lachiewicz et al. Citation2012). Gaps between the TM component and the bone are filled with morsellised bone (Meneghini et al. Citation2009) or bone cement (Radnay and Scuderi Citation2006). The final prosthesis is then cemented to the surface of the TM component and the surrounding bone (Meneghini et al. Citation2009). A monoblock tantalum tibial component has also been developed for knee replacement surgery, which can be used with or without cement under the tray (but not around the posts) depending on the bone quality (Bobyn et al. Citation2004). The interface bonding strength between TM and bone cement is therefore of importance, but has not yet been evaluated. In contrast, the bone/cement interface has been thoroughly evaluated since Charnley popularized the technique of cementing prostheses.

We evaluated the stability of a porous implant/cement interface by comparing it to the well-studied bone/cement interface control standard, by using axial pullout and torsional failure tests. We hypothesized that the limiting factor of the interface would be the cement component, and that there would be little difference between the 2 study groups.

Material and methods

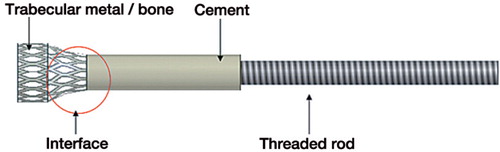

The study consisted of 2 experiments to evaluate interface strength between bone and cement, and between a porous metal and cement. Both experiments each involved 10 cancellous bone cylinders and 10 porous metal cylinders of the same geometry. The interface testing area of each probe consisted of 3 regions: the region consisting of only bone or porous metal, the region consisting of bone and cement or porous metal and cement, and the region consisting of only cement ().

Figure 1. Schematic drawing of a probe used for testing. The cylindrical end with porous metal/bone had a diameter and height of 10 mm, with a tapered top 6 mm in diameter where the probe was anchored to the PMMA.

The first experiment evaluated the axial pullout force of the probes and the second experiment evaluated the interface strength under torsion. Both tests were terminated at the point of failure or discernable plastic deformation of the samples.

The local ethics committee approved the study (S-251/2008).

Creation of the testing cylinders

The cancellous bone cylinders were taken from 10 fresh frozen human femoral heads from 5 donors in accordance with the recommendations of Morgan and Keaveny (Citation2001) and Keaveny et al. (Citation1994). A cylindrical carving tool was used to remove the bone from the recommended femoral head regions; care was taken to prevent dehydration of the bone. Bone used for testing was excluded if the donor had suffered from neoplastic disease, osteoporosis, or prior hip surgery. After radiographic exclusion of lytic or osteoblastic bone lesions, the bone mineral density (BMD) was evaluated using DEXA (QDR-2000 DXA densitometer; Hologic Inc., Waltham, MA).

The cancellous bone cylinders were cut to 10 mm diameter and 10 mm height. The upper end of the cylinders, where cement was to be applied, was tapered to 6 mm in diameter to minimize stress rising and limit failure to the narrowed gauge, as described by Bergmann et al. (Citation1977). This was also done in order to reduce the effects of the fixation on the results in the interface region. Similar tapered gauges are commonly seen in other standardized materials tensile testing setups. The bone cylinders were then cemented as described below, to create the probes for the bone/cement group.

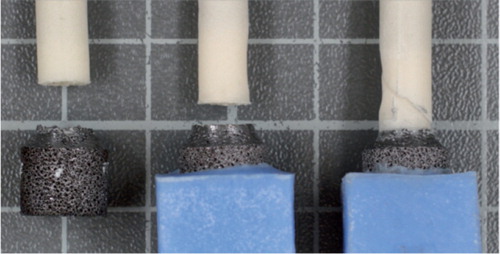

The porous metal cylinders (Trabecular Metal Rod; Zimmer, Warsaw, IN) were fabricated with the same size and shape as the cancellous bone cylinders. The geometry was created using a wire-cut electric discharge machining process. These were also cemented as described below, to create the probes for the porous metal/cement interface ().

A medium-viscosity bone cement (Hi-Fatigue; Zimmer) was vacuum-mixed (EASYMIX Pro Bone Cement Mixing System; Zimmer) and applied 120 seconds after starting mixing. Cementing was performed under standardized room conditions with a mean room temperature of 20.1°C ± 0.4°C and mean humidity of 38.6% ± 8.8%. All the bone cylinders were thoroughly lavaged and then warmed to body temperature using an incubator prior to cementing. For cementing, the probes of both groups were fixed in a custom-made frame and container, and a cement pressure of 1.2 N/mm2 was applied to the standardized surface area. An identical cementing pressure was used throughout using a linear motor (ET100; Parker Hannafin GmbH & Co. KG Electromechanical Automation, Offenburg, Germany) with a proportional integral derivative controller (Compax3 T40; Parker Hannafin), as had been done in previous experimental setups (Bitsch et al. Citation2010, Citation2011). The cross-sectional area of the interface was determined before testing. We measured each probe 3 times using a digital caliper and calculated the mean interface diameter of each probe.

Axial pull out force, or tensile test experiment

After creation of the cancellous bone cylinders and porous metal cylinders, the bone or porous metal portion of the probe was coupled to the materials testing machine (MTS Minibionix 359; MTS, Eden Prairie, MN) using a custom-made fixture frame to eliminate shear forces. The interface stability analyses were done using a pullout test with a set displacement rate of 0.35 mm/min. The tensile strength for both groups investigated was then calculated; the maximum tensile strength was calculated from the maximum force that resulted in failure divided by the cross-sectional area at the point of failure.

Torsional failure experiment

The probes created were fixed by their bone cement to a chuck, which was in turn attached to an interpositioned torsion sensor (D-2431; Lorenz Messtechnik GmbH, Alfdorf, Germany) connected to the articulating portion of the materials testing machine. The opposite side of the probes was secured in a 2-component casting resin (RenCast FC53 A/B; Goessl & Pfaff, Munich, Germany), which allowed fixation in the anchoring device.

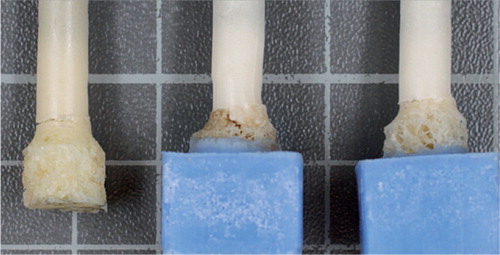

The loading was done at a fixed rotational rate of 30°/min, or 0.524 radians/min, until failure was noted. The torsional failure force was recorded, and the rotational stiffness was calculated for both groups investigated. Failure was recognized by a sudden and marked change in the measured force (either tensile or torsional), frequently coinciding with a macroscopically visible discontinuity at the interface ( and ).

Figure 2. Representative examples of failure at the interface of the bone probes. On the left is an example of tensile failure. In the middle and on the right are examples of failure under torsion.

Figure 3. Representative examples of the failure modes of the porous metal-cement interface probes. On the left is an example of tensile failure. In the middle and on the right are examples of torsional failure.

The pullout and torsional tests were performed in accordance with various standards (EN 10002, DIN 54455:1984-05, ISO5833) since a variety of materials were used. The test parameters have also been reported previously (Schlegel et al. Citation2011). In order to confirm that the rate of tension increase was appropriate, we performed pre-tests.

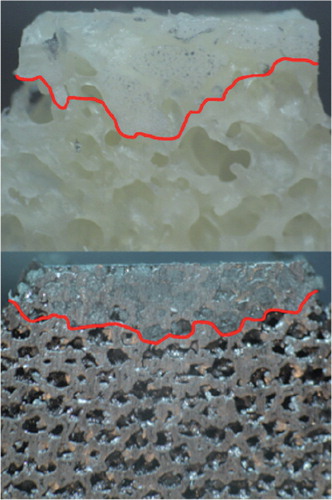

Evaluation of cement penetration

After completing the experiments, the probes were cut sagittally by using a diamond band saw with a 0.3-mm diamond saw blade. The probes were then placed under a stereo microscope and photographed. The amount of cement penetration was scaled and then measured using ImageJ, software (freeware) developed at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Schneider et al. Citation2012).

Statistics

The data were evaluated descriptively using the arithmetic mean, standard deviation (SD), and minimum and maximum. We performed a cluster sample analysis with a linear mixed-effects model using a reduced maximum-likelihood approach (REML) to evaluate and compare the relatively homogeneous groups and compensate for repeated observations due to the limited donor number. In addition, we carried out a sensitivity analysis using the Mann-Whitney U-test. To do the latter, we used the mean of the bone samples from each donor and compared these with the metal samples. The test was 2-sided and a p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical evaluation was performed using the analytical software IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows.

Results

The femoral bone had a mean BMD of 0.79 (SD 0.19) (0.62–1.10) g/cm2, as measured using DXA scan, in the tensile test group whereas the torsional test group had a mean BMD of 0.74 (SD 0.16) (0.62–1.10) g/cm2 ( and ).

Table 1. Results of the tensile test

Table 2. Results of the torsion test

Tensile testing

In both groups, the rupture line was located at the interface region of the cement and the bone or porous metal cylinders. In the bone/cement group, some of the specimens showed a full-thickness cement crack with few intact cancellous bone trabeculae between the 2 components ( and ).

The porous metal/cement interface was superior to the bone/cement interface regarding both tensile strength (p < 0.001) and maximal tensile force (p < 0.001) ( and ).

Torsional testing

As found with the tensile tests, the most frequent failure location was at the interface between cement and bone or porous metal ( and ,, and ).

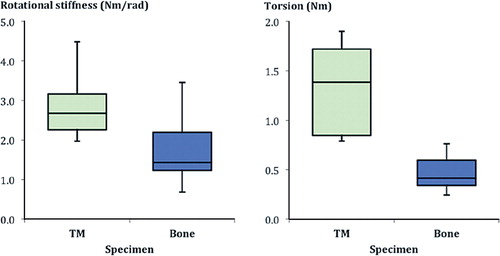

Figure 5. Box plot of the rotational stiffness and maximal torsion shown by the porous metal (TM) and the bone specimens.

The mode of failure varied, however, from that seen in the pullout tests. The porous metal samples showed a spiral fracture extending along the cement in 6 of 10 cylinders, and the remaining 4 showed transverse fracture morphology at the porous metal/cement interface (), specifically at the plane between pure cement and porous metal/cement interdigitation. The bone cylinders displayed a spiral fracture of the cancellous bone in 4 of 10 probes, and the remainder showed transverse fractures at the bone/cement interface (). This demonstrates that failure occurred in differing interface regions, namely the predominantly cement region of the porous metal/cement specimens, in contrast to the areas of failure containing both bone and cement or only bone in the bone/cement specimens. The mean maximal torsion for the porous metal/cement interface was greater than that seen with the bone/cement interface. This was also the case with rotational stiffness. These differences were all statistically significant.

Cement penetration

The porous metal probes had a mean cement penetration of 1.69 (SD 0.47) (0.59–2.36) mm. The bone probes had a mean cement penetration of 3.65 (SD 0.71) (1.74–4.53) mm (p (cluster analysis) < 0.001; p (U-test) < 0.001). Examples of the cement penetration can be seen in .

Discussion

The bone/cement interface in hip arthroplasty has been well studied (Kolbel and Boenick Citation1972, Kolbel et al. Citation1973, Bergmann et al. Citation1977, Mann et al. Citation1997b, Citation1999, Bitsch et al. Citation2010, Citation2011) and its importance in the overall stability of a cemented prosthesis is well known (Breusch and Malchau Citation2005, Bitsch et al. Citation2011). In vivo, there are many factors that influence the stability of a bone/cement interface including lavage, bone density, hemostasis, the cement application technique, the consistency of the cement, and the heat created during cement application (Askew et al. Citation1984, Benjamin et al. Citation1987, Bannister and Miles Citation1988, Breusch and Malchau Citation2005, Bitsch et al. Citation2010, Citation2011, Aro et al. Citation2012). In vitro, most of these factors do not apply—with the exception of those related to the cement. The bone/cement interface, which has been well studied, provides an excellent control group for comparison to the porous metal/cement interface.

Interface testing between 2 materials such as bone cement and bone usually involves the determination of axial pullout or tensile forces (Kolbel and Boenick Citation1972, Bergmann et al. Citation1977, Mann et al. Citation1997a, Citation1999, Erhart et al. Citation2011, Miller et al. Citation2011), shear forces (Kolbel et al. Citation1973, Amirfeyz and Bannister Citation2009), and rotational forces (Erhart et al. Citation2011) needed to cause failure (force at failure). To our knowledge, the porous metal/cement interface has not been tested previously.

Koelbel and Boenick (1972) and Bergmann and Koelbel (1977) tested the mechanical strength of the bone/cement interface by using pullout forces along the longitudinal axis of the specimen in the interface zone, or zone of bonding. They found, with identical cementing technique, that the forces at failure depended upon the consistency of the bone structure and quality, and the proportion of bone to cement in the zone of bonding. If the bone was less dense, the cancellous clefts were wider, allowing larger cement pegs to extend into the cancellous bone. Under these circumstances, the interface fractures occurred within the bone. Dense bone had thin cancellous clefts and the cement pegs were consequently narrower; under these circumstances, interface fractures occurred within the cement. In addition, Koelbel and Boenick (1973) found that shear forces at failure occurred at 160 kp/cm2 in less dense bone, whereas in dense bone shear forces at failure occurred at or above 240 kp/cm2. The bone used in our experiments (with a mean bone density of 0.79 g/cm2 for the tensile test and 0.74 g/cm2 for the torsional test) was in the middle range for healthy American men between the ages of 60 and 69 years (Looker et al. Citation1995).

In other studies, increased depth of cement penetration has been shown to improve implant stability (Halawa et al. Citation1978, MacDonald et al. Citation1993, Waanders et al. Citation2010). Cement of thin consistency and defects occurring in the cement mantle have resulted in increased loosening of a component (Mulroy et al. Citation1995). Further studies have shown that the tensile strength of the bone/cement interface is dependent upon the degree of bone/cement interdigitaton (Mann et al. Citation1997a). Despite these varied reports on the failure properties of cemented bone, the maximum tensile strengths seen in our experiments were similar to those seen in the literature (Kolbel and Boenick Citation1972, Krause et al. Citation1982, Mann et al. Citation1997a). In our opinion, this reflects a standardized setup with realistic testing parameters at mean cementation depths in the range of those recommended in the literature (Walker et al. Citation1984, Breusch and Malchau Citation2005).

The porous metal investigated has been shown to provide a 75–85% volume porosity (Levine Citation2008). Various authors have described the excellent biocompatibility of the tantalum porous metal selected (Bobyn et al. Citation1999a, Levine Citation2008, Pulido et al. Citation2011). Advantages include a 75–85% volume porosity (Levine Citation2008) with a tantalum lattice or reticular structure, allowing earlier and greater bone ingrowth than with conventional coatings (Bobyn et al. Citation1999a, Pulido et al. Citation2011), an elasticity similar to native bone, avoidance of stress shielding (Pulido et al. Citation2011), and a high coefficient of friction (Levine Citation2008). The porosity potentially allows a large amount of cement to interdigitate with the porous material during cemented implantation. The clinical significance of cementation of a porous implant is currently unclear. Cementation of the porous implant to bone may, however, result in detrimental effects on the porous implant. It is evident that cementing of trabecular metal directly to native bone will obviate all the advantages of porous metal—such as accelerated bone ingrowth, reduced stress shielding, and the high friction with bone.

When we compared the force to failure of the bone/cement interface to that of the porous metal/cement interface, we found that the differences were statistically significant, with substantial effect size. Both tensile strength and rotational strength of the porous metal/cement interface were consistently greater in all experiments than those found with the bone/cement interface. In addition, our results indicated that the porous metal was less likely to be the interface strength-limiting factor compared to bone, since half of the bone samples showed fractures, while none of the porous metal samples suffered fractures.

Our experimental results are presented here with several caveats. The use of cadaver bone rather than live bone avoids the occurrence of superficial thermal necrosis at the bone/cement interface caused by heat generated during cementation (Bergmann et al. Citation1977). Also, the use of cadaver bone avoids certain intraoperative issues that can interfere with cementing, such as bleeding and the presence of fat and marrow (although reduced by lavage) (Bitsch et al. Citation2007). These issues most likely further increase the difference in strength between the porous metal/cement interface and the bone/cement interface.

Although we consistently applied the same cementation pressure to all probes in order to simulate the surgical setting, we did not confirm that all samples had similar cement penetration prior to experimental testing. Subsequent evaluation showed that the porous metal had less cement penetration than the bone, presumably because of a different degree of porosity and surface roughness. Previous studies, such as that by Bitsch et al. (Citation2010), have shown that bone porosity affects cement penetration. Despite the differing depth of penetration, the porous metal/cement interface was consistently and significantly more stable in the biomechanical tests.

The nature of the bone samples, the limited number of donors, and the multiple probes obtained from their femoral heads inevitably result in slight bias and in correlated observations, as described by Ranstam (Citation2012). This is, however, a limitation of the many in vitro setups. To compensate for this, and to minimize the effect of repeated observations, we performed the cluster sample analysis with a linear mixed-effects model as well as a confirmatory Mann-Whitney U-test with the bone samples from each donor grouped to a single mean value to provide independent results.

In addition, creation of the porous metal probes could have altered the mechanical properties of the probes, as a result of annealing or tantalum hardening. We estimate, however, that this effect is negligible with regard to the interface stability tests. Furthermore, this testing scenario evaluated initial stability in an in vitro setting and not under physiological, dynamic conditions such as cyclical loading. Finally, our experimental setup did not permit testing of the uncemented porous metal/bone interface.

In summary, our in vitro studies showed that the tensile and rotational strength of the porous metal/cement interface was greater in all instances than that of the bone/cement interface, despite shallower cement penetration with the same cementing pressure. We therefore hypothesize that the trabecular metal/cement interface would not compromise the primary stability of a multicomponent revision construct containing porous metal components.

NAB: conception of study, data collection, discussion, statistics, and writing. RGB: supervision, discussion, and review. JBS: planning of study, supervision, and discussion. MCMM: data handling, discussion, and review. JPK: review and discussion. SJ: planning and conception of study, data collection, discussion, statistics, review, and discussion.

Funding for this project was provided by a research grant from the local county and the University of Heidelberg. None of the authors received financial gain directly associated with this work. Some of the authors have received grants or financial relationships outside the work described: SJ has received research and institutional support from Biomet, Implantcast, Smith & Nephew, Zimmer, and DePuy. RGB has received grants from DePuy and has received research and institutional support from Biomet, Implantcast, Smith & Nephew, Zimmer, and DePuy. JPK has received grants from DePuy, Link, Biomet, Questmed, Ceramtec, Falcon Medical, and Corin; he has also received payment for lectures and/or consultancy from Ceramtec, Aesculap, Hofstetter, DePuy, and Smith & Nephew, and he is a board member of DePuy, Germany. NAB, MCMK, and JBS have not received grants or other financial benefits from external companies/corporations.

- Amirfeyz R, Bannister G. The effect of bone porosity on the shear strength of the bone-cement interface. Int Orthop 2009; 33 (3): 843-6.

- Aro HT, Alm JJ, Moritz N, Makinen TJ, Lankinen P. Low BMD affects initial stability and delays stem osseointegration in cementless total hip arthroplasty in women: a 2-year RSA study of 39 patients. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (2): 107-14.

- Askew MJ, Steege JW, Lewis JL, Ranieri JR, Wixson RL. Effect of cement pressure and bone strength on polymethylmethacrylate fixation. J Orthop Res Soc 1984; 1 (4): 412-20.

- Bannister GC, Miles AW. The influence of cementing technique and blood on the strength of the bone-cement interface. Eng Med 1988; 17 (3): 131-3.

- Beckmann NA, Weiss S, Klotz MC, Gondan M, Jaeger S, Bitsch RG. Loosening after acetabular revision: comparison of trabecular metal and reinforcement rings. A systematic review. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29 (1): 229-35.

- Benjamin JB, Gie GA, Lee AJ, Ling RS, Volz RG. Cementing technique and the effects of bleeding. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1987; 69 (4): 620-4.

- Bergmann G, Kolbel R, Rohlmann A. Mechanical properties of bonding between cancellous bone and polymethylmetacrylate. IV. Tensile fatigue strength. Arch Orthop Unfallchir 1977; 87 (2): 223-33.

- Bitsch RG, Heisel C, Silva M, Schmalzried TP. Femoral cementing technique for hip resurfacing arthroplasty. J Orthop Res Soc 2007; 25 (4): 423-31.

- Bitsch RG, Jager S, Lurssen M, Loidolt T, Schmalzried TP, Clarius M. Influence of bone density on the cement fixation of femoral hip resurfacing components. J Orthop Res Soc 2010; 28 (8): 986-91.

- Bitsch RG, Jager S, Lurssen M, Loidolt T, Schmalzried TP, Weiss S. The influence of cementing technique in hip resurfacing arthroplasty on the initial stability of the femoral component. Int Orthop 2011; 35 (12): 1759-65.

- Bobyn JD, Stackpool GJ, Hacking SA, Tanzer M, Krygier JJ. Characteristics of bone ingrowth and interface mechanics of a new porous tantalum biomaterial. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1999a; 81 (5): 907-14.

- Bobyn JD, Toh KK, Hacking SA, Tanzer M, Krygier JJ. Tissue response to porous tantalum acetabular cups: a canine model. J Arthroplasty 1999b; 14 (3): 347-54.

- Bobyn JD, Poggie RA, Krygier JJ, Lewallen DG, Hanssen AD, Lewis RJ, . Clinical validation of a structural porous tantalum biomaterial for adult reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 2) 2004; 86: 123-9.

- Breusch SJ, Malchau H. The well-cemented total hip arthroplasty: theory and practice. Springer: Berlin; New York 2005.

- Erhart S, Schmoelz W, Blauth M, Lenich A. Biomechanical effect of bone cement augmentation on rotational stability and pull-out strength of the proximal femur nail antirotation. Injury 2011; 42 (11): 1322-7.

- Halawa M, Lee AJ, Ling RS, Vangala SS. The shear strength of trabecular bone from the femur, and some factors affecting the shear strength of the cement-bone interface. Arch Orthop Unfallchir 1978; 92 (1): 19-30.

- Jensen CL, Petersen MM, Schroder HM, Flivik G, Lund B. Revision total knee arthroplasty with the use of trabecular metal cones: a randomized radiostereometric analysis with 2 years of follow-up. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27 (10): 1820-6 e2.

- Keaveny TM, Guo XE, Wachtel EF, McMahon TA, Hayes WC. Trabecular bone exhibits fully linear elastic behavior and yields at low strains. J Biomech 1994; 27 (9): 1127-36.

- Kolbel R, Boenick U. Mechanical properties of bonding between cancellous bone and polymethylmetacrylate. I. Tensile strength. Arch Orthop Unfallchir 1972; 73 (1): 89-97.

- Kolbel R, Boenick U, Krieger W, Wilk R. Mechanical properties of bonding between cancellous bone and polymethylmethacrylate. II. Shear strength. Arch Orthop Unfallchir 1973; 77 (4): 339-47.

- Krause WR, Krug W, Miller J. Strength of the cement-bone interface. Clin Orthop 1982; (163): 290-9.

- Lachiewicz PF, Bolognesi MP, Henderson RA, Soileau ES, Vail TP. Can tantalum cones provide fixation in complex revision knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop 2012; (470) (1): 199-204.

- Levine B. A new era in porous metals: Applications in orthopaedics. Adv Eng Mat 2008; 10 (9): 788-92.

- Levine B, Della Valle CJ, Jacobs JJ. Applications of porous tantalum in total hip arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2006; 14 (12): 646-55.

- . Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Calvo MS, Harris TB, Heyse SP, et al.. Proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int 1995; 5 (5): 389-409.

- MacDonald W, Swarts E, Beaver R. Penetration and shear strength of cement-bone interfaces in vivo. Clin Orthop 1993; (286): 283-8.

- Mann KA, Ayers DC, Werner FW, Nicoletta RJ, Fortino MD. Tensile strength of the cement-bone interface depends on the amount of bone interdigitated with PMMA cement. J Biomech 1997a; 30 (4): 339-46.

- Mann KA, Werner FW, Ayers DC. Modeling the tensile behavior of the cement-bone interface using nonlinear fracture mechanics. J Biomech Eng 1997b; 119 (2): 175-8.

- Mann KA, Werner FW, Ayers DC. Mechanical strength of the cement-bone interface is greater in shear than in tension. J Biomech 1999; 32 (11): 1251-4.

- Meneghini RM, Lewallen DG, Hanssen AD. Use of porous tantalum metaphyseal cones for severe tibial bone loss during revision total knee replacement. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 2) 2009; 91 Pt 1: 131-8.

- Miller MA, Race A, Waanders D, Cleary R, Janssen D, Verdonschot N, . Multi-axial loading micromechanics of the cement-bone interface in postmortem retrievals and lab-prepared specimens. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2011; 4 (3): 366-74.

- Morgan EF, Keaveny TM. Dependence of yield strain of human trabecular bone on anatomic site. J Biomech 2001; 34 (5): 569-77.

- Mulroy WF, Estok DM, Harris WH. Total hip arthroplasty with use of so-called second-generation cementing techniques. A fifteen-year-average follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1995; 77 (12): 1845-52.

- Pulido L, Rachala SR, Cabanela ME. Cementless acetabular revision: past, present, and future. Revision total hip arthroplasty: the acetabular side using cementless implants. Int Orthop 2011; 35 (2): 289-98.

- Radnay CS, Scuderi GR. Management of bone loss: augments, cones, offset stems. Clin Orthop 2006; (446): 83-92.

- Ranstam J. Repeated measurements, bilateral observations and pseudoreplicates, why does it matter? Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012; 20 (6): 473-5.

- Schlegel UJ, Siewe J, Delank KS, Eysel P, Puschel K, Morlock MM, . Pulsed lavage improves fixation strength of cemented tibial components. Int Orthop 2011; 35 (8): 1165-9.

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri K W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 2012; 9 (7): 671-5.

- Waanders D, Janssen D, Mann KA, Verdonschot N. The mechanical effects of different levels of cement penetration at the cement-bone interface. J Biomech 2010; 43 (6): 1167-75.

- Walker PS, Soudry M, Ewald FC, McVickar H. Control of cement penetration in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 1984; (185): 155-64.