Abstract

Background — The surgical approach in total hip arthroplasty (THA) is often based on surgeon preference and local traditions. The anterior muscle-sparing approach has recently gained popularity in Europe. We tested the hypothesis that patient satisfaction, pain, function, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) after THA is not related to the surgical approach.

Patients — 1,476 patients identified through the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register were sent questionnaires 1–3 years after undergoing THA in the period from January 2008 to June 2010. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) included the hip disability osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS), the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC), health-related quality of life (EQ-5D-3L), visual analog scales (VAS) addressing pain and satisfaction, and questions about complications. 1,273 patients completed the questionnaires and were included in the analysis.

Results — Adjusted HOOS scores for pain, other symptoms, activities of daily living (ADL), sport/recreation, and quality of life were significantly worse (p < 0.001 to p = 0.03) for the lateral approach than for the anterior approach and the posterolateral approach (mean differences: 3.2–5.0). These results were related to more patient-reported limping with the lateral approach than with the anterior and posterolateral approaches (25% vs. 12% and 13%, respectively; p < 0.001).

Interpretation — Patients operated with the lateral approach reported worse outcomes 1–3 years after THA surgery. Self-reported limping occurred twice as often in patients who underwent THA with a lateral approach than in those who underwent THA with an anterior or posterolateral approach. There were no significant differences in patient-reported outcomes after THA between those who underwent THA with a posterolateral approach and those who underwent THA with an anterior approach.

The approach used for total hip arthroplasty (THA) is often based on the surgeon’s preference and local traditions. In 2011, 7,360 primary THAs were reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) (Norwegian Arthroplasty Register Annual Report 2012). A lateral approach was used in 53% of the operations, the posterolateral approach in 28%, and an anterior approach in 16%. Anterior muscle-sparing approaches have gained popularity because it has been argued that patients with such surgical approaches have less pain, shorter length of stay, and shorter rehabilitation time. These are short-term effects (Rodriguez et al. Citation2014), and the long-term effects are not well documented.

The anterior approaches used in Norway are either a modified Smith-Petersen approach (Smith-Petersen Citation1949, Judet and Judet Citation1950) or an anterolateral Watson-Jones approach (Watson-Jones Citation1936). These may have a longer learning curve (Greidanus et al. Citation2013) and a higher incidence of early revision (Spaans et al. Citation2012, Lindgren et al. Citation2012). The lateral approach (Hardinge Citation1982) divides the anterior portion of gluteus medius and minimus. Muscular-tendon suture or osteosuture is used to reinsert the tendon into the trochanteric area. This approach has been blamed for increasing the risk of damage to the superior gluteal nerve and to the gluteus medius muscle (Jolles and Bogoch Citation2006, Arthursson et al. Citation2007, Khan and Knowles Citation2007).

The posterolateral approach involves division of the piriformis, obturator internus, and gemelli tendons (Pellicci et al. Citation1998). This approach is considered to have less effect on gait since the abductor muscles are not dissected (Shaw Citation1991, Hedlundh et al. Citation1995), but it has been associated with an increased risk of dislocations, with risk of injury to the sciatic nerve. More recent studies have shown that use of larger femoral head sizes can markedly reduce the dislocation rate (Amlie et al. Citation2010, Bistolfi et al. Citation2011, Ho et al. Citation2012).

We compared the different approaches with regard to patient satisfaction, pain, function, and HRQoL after primary THA.

Patients and methods

Patients were identified through the NAR, a population-based prospective clinical database for arthroplasty operations that was established in 1987 (Havelin et al. Citation2000). Eligible patients were registered in the NAR as having undergone THA for primary osteoarthritis between January 2008 and June 2010, with femoral head size of 28 mm or 32 mm, and aged between 50 and 80 years. A unique identification number is used to track the patient’s present address and status as alive or dead. PROMs are not registered prospectively in the NAR and preoperative values were therefore not available. Patients registered before 2011 with bilateral THA or trochanteric osteotomy were excluded. To minimize the potentially confounding influence of the learning curve for each approach, patients were recruited from hospitals doing more than 25 THAs a year using the same approach.

Surgical approach was categorized as anterior, posterolateral, or lateral. THAs using an anterior approach involved splitting of the intermuscular space on either side of the tensor fasia lata, and 498 patients from 8 hospitals were verified as having an anterior approach. None of the THAs with an anterior approach had a cemented femoral stem and therefore, to enhance comparability, cemented stems were excluded for the other approaches. Of the patients who underwent THA with a posterolateral approach, 228 had reverse hybrid fixation and 250 were randomly selected from those with an uncemented prosthesis (13 hospitals). Patients who underwent THA with a lateral approach were randomly selected from reverse hybrid (250) and uncemented (250) THAs in 24 hospitals.

The average number of operations performed per hospital in the study period was 189 for anterior approach, 226 for lateral approach, and 325 for posterolateral approach. Subsets of data were analyzed for Charnley group A, excluding patients who reported planned THA on the other side or having had a new THA not registered in NAR when questionnaires were prepared. Subsets of data were also examined for possible beneficial effects of high-volume surgery in 3 hospitals using the posterolateral approach.

Questionnaire

A follow-up questionnaire assessing postoperative complications, reoperations, pain, patient satisfaction, function, daily activities, sport/recreation, and health-related quality of life were distributed to the 1,476 patients identified for inclusion. The questionnaire was in 4 parts:

1. Visual analog scales (VAS) was used to assess pain and patient satisfaction. VAS scores ranged from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating less pain (or no pain) and more satisfaction.

2. The hip disability osteoarthritis score (HOOS) (Nilsdotter et al. Citation2003) is a self-administered questionnaire with 40 items assessing 5 subscales (symptoms, pain, activities of daily living (ADL), sport/recreation, and quality of life). Each item has 5 standardized answers ranging from none/never to extreme/always. Subscale scores are calibrated to 0–100 scales where 100 is the best score. 1 or 2 missing values were substituted with the average value for that subscale. If more than 2 items were omitted, the response was considered invalid and the subscale score was excluded from analysis. We used a validated Norwegian version (http://koos.nu). The HOOS includes the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) LK 3.0 in its complete and original format, and thus the WOMAC score (Bellamy et al. Citation1988) was calculated directly from the HOOS.

3. EQ-5D HRQoL is a standardized instrument for use as a measure of health outcome, consisting of a descriptive system and a visual analog scale (EuroQol Group Citation1990). To calculate the EQ-5D index in this study, the European VAS-based value set was used (Greiner et al. Citation2003). The EQ-5D index is represented on a scale with a best score of 1 and lower (sometimes negative) scores indicating worse HRQoL. The EQ-5D-3L instrument also includes a VAS score (0–100) where the patient rates his/her overall health status. Only completed forms were accepted. We used a validated Norwegian version (http://www.euroqol.org).

4. Patients marked whether the contralateral hip had been operated or whether THA was planned on the other side. They were asked to report whether the operation on the hip in question had led to limping and whether the operation had caused nerve injury or dislocation. They were also asked whether reoperation in the same hip had occurred, either because of infection or for any other reason. Based on the patients’ answers, those meeting criteria for Charnley category A (unilateral hip involvement only) were identified for subgroup analysis.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics are provided as mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Group comparisons were conducted using t-tests and chi-square tests.

None of the PROMs were normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk test). The EQ-5D and WOMAC had a marked ceiling effect, so the underlying assumption for using parametric or non-parametric tests was not fulfilled and these measures were therefore excluded from statistical analysis. According to common practice (Jansson and Granath Citation2011), we present the PROMs as means and SD values. Cohen’s d was used as a standard measure of effect size. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to evaluate the mean differences for HOOS subscores, EQ VAS score, patient satisfaction, and pain between approaches. The regression models also adjusted for variables that were significantly different between the approaches (i.e. follow-up time and femoral head size).

We used log-binomial regression to estimate relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of categorical outcomes (e.g. limping). 2-tailed p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We used Qlikview to visualize the dataset, and it was also used for initial statistical analyses. SPSS for Windows version 18 was used for all other analyses.

Ethics

The Norwegian Regional Ethical Committee for medical and health-related research ethics (REK South-East) approved the study (2011/1737a), which was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. The patients received written information about the study, and all participants signed an informed consent document.

Results

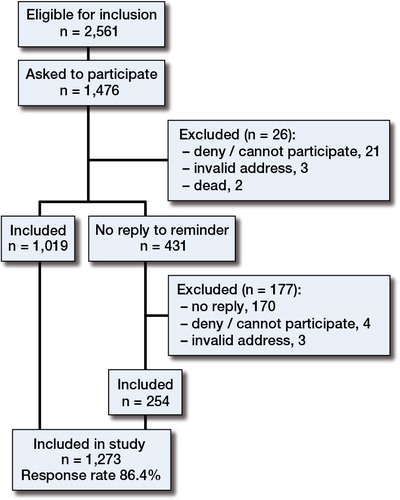

1,273 of 1,476 patients were included after returning the questionnaires. The 203 non-responders included patients who did not answer after a reminder (170) and patients who did not want to or were unable to participate (25). We were unable to reach 6 patients and 2 patients had died (). The overall response rate was 86%, irrespective of surgical approach. There were similar distributions of sex and follow-up time for responders and non-responders. However, of those who underwent THA with a lateral approach, the non-responders were generally older (mean 69 years, SD 7.1) than the study participants (mean 66 years, SD 7.3; p = 0.001).

Mean age, sex, and ASA class were equally distributed in patients who underwent THA with the different approaches (). Average femoral head diameter was greater in patients who underwent THA with the posterolateral approach than in those who underwent THA with anterior and lateral approaches. In posterolateral patients, the proportion of those with 32-mm head size increased from 45% to 72% during the study period. The groups also differed regarding follow-up time, with the anterior approach having a shorter mean follow-up time than the other 2 approaches.

Table 1. Patient characteristics by surgical approach (n = 1,273)

HOOS, WOMAC, and EQ-5D index

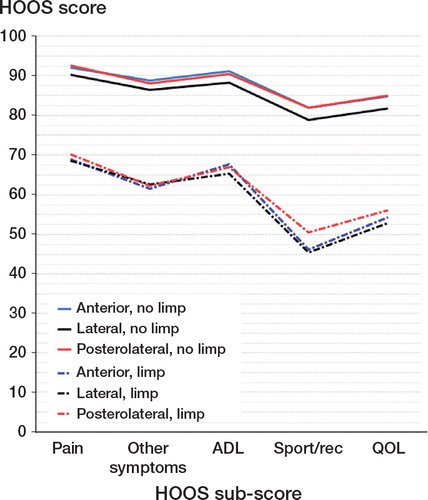

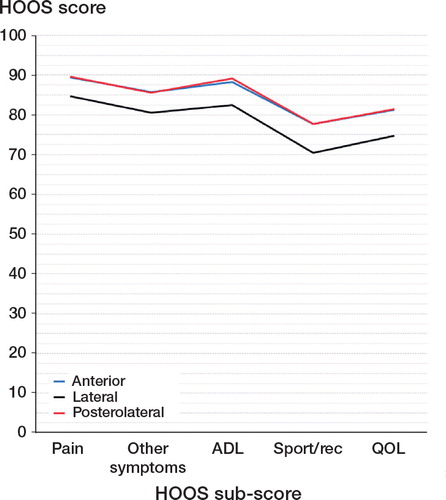

We regarded HOOS to be the most reliable PROM used in the study because it had the least skewed distribution. The average HOOS subscores 1–3 years after THA were almost identical for the anterior and posterolateral approaches, and varied from 89 (pain) to 77 (sport/recreation) (). The lateral approach was associated with worse outcome on all HOOS subscales (, ), and when adjusted for femoral head size and follow-up time, the mean differences between the lateral approach and the anterior or posterolateral approach varied from 3.2 to 5.0 (). The average WOMAC score calculated was 83 (SD 19) for lateral approach, 88 (SD 16) for anterior approach, and 88 (SD 16) for posterolateral approach. The average EQ-5D index was 0.80 (SD 0.22) for lateral approach, 0.86 (SD 0.19) for anterior approach, and 0.86 (SD 0.19) for posterolateral approach. WOMAC and EQ-5D also showed the lowest scores for the lateral approach, as for HOOS. However, the WOMAC score and EQ-5D had a marked ceiling effect, and therefore statistical tests for differences between groups were not performed.

Figure 2. HOOS subscores. Crude means for patients after having undergone THA with anterior, lateral, or posterolateral approach. Lateral approach was associated with significantly lower scores than anterior and posterolateral approaches on all subcsales (SD 16.3–26.2).

Table 2. HOOS subscores. Mean differences in outcome in patients who underwent THA with different approaches, adjusted for femoral head size and follow-up time

EQ VAS, patient satisfaction, and pain

The average EQ VAS score, reflecting overall health status 1–3 years after operation, was 79 (SD 20). Average score for patient satisfaction was 87 (SD 23), and the average pain score (where no pain = 100) was 88 (SD 19). The anterior and posterolateral approaches were similar (adjusted mean difference: 0.2–1.2 units) on the 3 VAS scales (). However, the lateral approach was associated with statistically significantly worse outcomes than the anterior approach and the posterolateral approach on the VAS scales for both patient satisfaction and pain in the operated hip. The effect size was most marked when comparing the posterolateral approach and the lateral approach on the VAS scales for pain and patient satisfaction (Cohen’s d = 0.30 and 0.31). In contrast, the EQ VAS score was similar with the 3 different approaches ().

Table 3. Crude means for each approach and adjusted mean differences in outcome for patients who underwent THA with lateral approach vs. anterior and posterolateral approaches

Patient-reported complications

In patients operated with a lateral approach, 25% reported that the operation had led to limping (). This was twice as high as in those operated with the anterior and posterolateral approaches, and the adjusted RR for patient-reported limping with a lateral approach was 2.0 (95% CI: 1.4–2.8) compared to the anterior approach and 1.9 (95% CI: 1.4–2.7) compared to the posterolateral approach.

Table 4. Patient-reported complications 1–3 years after THA

Nerve injury was most commonly reported by patients operated with a lateral approach (6.3%) or an anterior approach (5.9%). Only 3.3% of those operated with the posterolateral approach reported nerve injury, and this group also had the lowest self-reported dislocation rate (2.4%), although these differences were not statistically significant. There was no difference in the number of reoperations due to infection in patients operated with different approaches. However, self-reported reoperations after THA due to other causes were higher (4.9%) for the lateral approach than for the anterior approach (1.9%) and the posterolateral approach (1.7%) (p = 0.007).

Effect of limping on other patient-reported outcomes

The difference in mean scores between limping and non-limping patients ranged from 17 to 35 on a scale of 0–100 for all PROM variables examined. Limping had a more serious effect on sport/recreation than on other subscores, particularly for patients who were operated with the anterior and lateral approaches (). When adjusting for limping and other relevant variables in a multiple regression model, the differences in PROMs (by approach) were almost eliminated. However, there was still a difference in HOOS ADL score between the lateral approach and the anterior approach (mean difference: 2.3; p = 0.05).

Subgroup analysis of Charnley category A patients

In the period between the last update of the NAR and the return of the questionnaire, 462 patients (36%) had either been operated on the other side or had a planned THA on the other side, and 811 patients (64%) had not been referred to hospital with hip problems on the contralateral side (Charnley category A). To ensure that the results were not unduly influenced by contralateral hip involvement, the group comparisons were repeated without patients who met the criteria for Charnley category B. Although patients in Charnley category A scored better irrespective of surgical approach, those operated with the lateral approach still scored significantly worse than those operated with the other approaches for almost every PROM. There were still no significant differences between the posterolateral approach and the anterior approach.

Subgroup analysis of hospitals

The posterolateral approach was used almost exclusively in 3 high-volume hospitals. To exclude a potentially beneficial effect of high-volume surgery in these hospitals, the analyses were repeated after excluding all the patients from these hospitals. The lateral approach was still associated with significantly worse outcomes for most PROMs, except that there was no significant difference between the lateral approach and the posterolateral approach in sport/recreation (p = 0.08) and EQ VAS (p = 0.3). There were still no significant differences between posterolateral approach and anterior approach.

Discussion

We found that 1–3 years after THA, the lateral approach was associated with worse outcomes than the anterior approach and the posterolateral approach for almost all patient-reported outcomes examined. The response rate was high (86%), but the cross-sectional design was a limitation. Surgery outcomes are largely dependent on the patient’s preoperative level of functioning. In this cross-sectional questionnaire study without the availability of preoperative measures, one cannot rule out the possibility that the results were confounded by preoperative group differences, a common limitation in such studies (Lygre et al. Citation2010, Leonardsson et al. Citation2013). However, preoperative functioning was not a criterion for the surgical approach chosen in this study, and the patient demographic characteristics and ASA classifications were similar for all 3 surgical approaches.

Although this study focused on patients who underwent primary unilateral THA, our findings may have been confounded by symptoms in the contralateral hip. However, analysis of the subgroup of patients classified as Charnley category A gave the same results, suggesting that contralateral hip involvement had little influence, thereby strengthening the study findings. The average number of approaches used per hospital also varied during the study period, but the main results were not affected when high-volume hospitals were excluded from the analysis.

HOOS was the most reliable scoring instrument in the present study, and the lateral approach was associated with worse outcomes on all HOOS subscales: pain, ADL, quality of life, sport/recreation, and other symptoms. Similar results were found in a recent study that compared the lateral approach and the posterolateral approach, with WOMAC scores being significantly lower for the lateral approach (Smith et al. Citation2012). The WOMAC and EQ-5D index used in this study were limited by serious ceiling effects. EQ-5D has been shown by others to have a bimodal distribution (Ostendorf et al. Citation2004, Jansson and Granath Citation2011, Rolfson et al. Citation2011) but this was not especially pronounced in our study. The use of a different value set for calculating the EQ-5D index and the fact that only postoperative data were collected may explain the less pronounced bimodality. Although this study generally used standardized PROMs with well-known psychometric properties, the questions regarding complications have not been formally validated, and this can be considered to be an additional weakness of the present study.

A recent study involving gait analysis found no differences between the 3 approaches in 36 patients (Queen et al. Citation2011). In the present study, the patients’ responses to the question of whether the operation had led to limping more than one year postoperatively would not necessarily match objective measurements or a clinical definition of limping. Nonetheless, the patients’ definition resulted in substantial differences between the limping group and the non-limping group for all PROMs examined, and patient-reported limping appears to account for most of the differences between the surgical approaches.

Self-reported limping occurred twice as often in patients who underwent THA with a lateral approach than in those who underwent THA with anterior or posterolateral approaches. Furthermore, limping appears to have been a greater problem in our study than in the literature in general (Picado et al. Citation2007). Limping may be caused by general fatigue, trochanteric pain, leg length discrepancy, lack of offset restoration, nerve injury (Khan and Knowles Citation2007), or insufficiency of the gluteal muscles. However, details of the causes of limping in the current study were not known. When we adjusted for limping, there were small but statistically significant differences in favor of an anterior approach over a lateral approach on ADL subscores. There was no significant difference between the anterior and posterolateral approaches. The posterolateral approach has been associated with a higher risk of dislocation (Arthursson et al. Citation2007, Lindgren et al. Citation2012). There has been considerable interest in dislocation rate and size of femoral head, and a 32-mm femoral head size has been shown to have a lower dislocation rate than smaller femoral heads (Bystrom et al. Citation2003). The introduction of highly crosslinked polyethylene has allowed the use of larger femoral heads in metal-polyethylene articulations (Callary et al. Citation2013). This has had a marked effect on choice of femoral head with the posterolateral approach, but it has had little or no effect on the choice of femoral head with lateral or anterior approaches during the study period. This may explain why the posterolateral approach had the lowest patient-reported dislocation rate in our study (2.4%). Various acetabular cups were used, but there is no reason to believe that these differences would affect patient-reported outcomes 1–3 years after operation.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that patient-reported outcomes are substancially worse for THA with a lateral approach than for THA with an anterior or posterolateral approach. The study also indicates that a change from the posterolateral approach to the anterior approach is probably of little benefit regarding pain and function. As PROMs are integrated in national registers (Rolfson et al. Citation2011), these results should be verified in large-scale longitudinal studies.

Study design: EA, LIH, OF, and SD. Data collection: EA and VB. Statistics: VB. All the authors were involved in writing of the manuscript.

We thank Caryl Gay, Research Specialist at University of California, San Francisco, for language editing.

No competing interests declared.

- Amlie E, Hovik O, Reikeras O. Dislocation after total hip arthroplasty with 28 and 32-mm femoral head. J Orthop Traumatol 2010; 11 (2): 111-5.

- Arthursson AJ, Furnes O, Espehaug B, Havelin LI, Soreide JA. Prosthesis survival after total hip arthroplasty—does surgical approach matter? Analysis of 19,304 Charnley and 6,002 Exeter primary total hip arthroplasties reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2007; 78 (6): 719-29.

- Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt L. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes following total hip or knee arthroplasty in osteoarthritis. J Orthop Rheumatol 1988; 1: 95-108.

- Bistolfi A, Crova M, Rosso F, Titolo P, Ventura S, Massazza G. Dislocation rate after hip arthroplasty within the first postoperative year: 36 mm versus 28 mm femoral heads. Hip Int 2011; 21 (5): 559-64.

- Bystrom S, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Havelin LI. Femoral head size is a risk factor for total hip luxation: a study of 42,987 primary hip arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop Scand 2003; 74 (5): 514-24.

- Callary SA, Field JR, Campbell DG. Low wear of a second-generation highly crosslinked polyethylene liner: a 5-year radiostereometric analysis study. Clin Orthop 2013; (471) (11): 3596-600.

- EuroQol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. The EuroQol Group. Health Policy 1990; 16 (3): 199-208.

- Greidanus NV, Chihab S, Garbuz DS, Masri BA, Tanzer M, Gross AE, Duncan CP. Outcomes of minimally invasive anterolateral THA are not superior to those of minimally invasive direct lateral and posterolateral THA. Clin Orthop 2013; (471) (2): 463-71.

- Greiner W, Weijnen T, Nieuwenhuizen M, Oppe S, Badia X, Busschbach J, Buxton M, Dolan P, Kind P, Krabbe P, Ohinmaa A, Parkin D, Roset M, Sintonen H, Tsuchiya A, de CF. A single European currency for EQ-5D health states. Results from a six-country study. Eur J Health Econ 2003; 4 (3): 222-31.

- Hardinge K. The direct lateral approach to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1982; 64 (1): 17-9.

- Havelin LI, Engesaeter LB, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Lie SA, Vollset SE. The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register: 11 years and 73,000 arthroplasties. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71 (4): 337-53.

- Hedlundh U, Hybbinette CH, Fredin H. Influence of surgical approach on dislocations after Charnley hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1995; 10 (5): 609-14.

- Ho KW, Whitwell GS, Young SK. Reducing the rate of early primary hip dislocation by combining a change in surgical technique and an increase in femoral head diameter to 36 mm. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2012; 132 (7): 1031-6.

- Jansson KA, Granath F. Health-related quality of life (EQ-5D) before and after orthopedic surgery. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (1): 82-9.

- Jolles BM, Bogoch ER. Posterior versus lateral surgical approach for total hip arthroplasty in adults with osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 3: CD003828.

- Judet J, Judet R. The use of an artificial femoral head for arthroplasty of the hip joint. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1950; 32 (2): 166-73.

- Khan T, Knowles D. Damage to the superior gluteal nerve during the direct lateral approach to the hip: a cadaveric study. J Arthroplasty 2007; 22 (8): 1198-200.

- Leonardsson O, Rolfson O, Hommel A, Garellick G, Akesson K, Rogmark C. Patient-reported outcome after displaced femoral neck fracture: a national survey of 4467 patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2013; 95 (18): 1693-9.

- Lindgren V, Garellick G, Karrholm J, Wretenberg P. The type of surgical approach influences the risk of revision in total hip arthroplasty: a study from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register of 90,662 total hipreplacements with 3 different cemented prostheses. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (6): 559-65.

- Lygre S HL, Espehaug B, Havelin LI, Furnes O, Vollset SE. Pain and function in patients after primary unicompartmental and total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2010; 92 (18): 2890-7.

- Nilsdotter AK, Lohmander LS, Klassbo M, Roos EM. Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS)—validity and responsiveness in total hip replacement. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2003; 4: 10.

- Norwegian Arthroplasty Register Annual Report 2012. http://nrlweb.ihelse.net/eng/Report_2012.pdf.

- Ostendorf M, van Stel HF, Buskens E, Schrijvers AJ, Marting LN, Verbout AJ, Dhert WJ. Patient-reported outcome in total hip replacement. A comparison of five instruments of health status. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2004; 86 (6): 801-8.

- Pellicci PM, Bostrom M, Poss R. Posterior approach to total hip replacement using enhanced posterior soft tissue repair. Clin Orthop 1998; (355): 224-8.

- Picado CH, Garcia FL, Marques W Jr. Damage to the superior gluteal nerve after direct lateral approach to the hip. Clin Orthop 2007; (455): 209-11.

- Queen RM, Butler RJ, Watters TS, Kelley SS, Attarian DE, Bolognesi MP. The effect of total hip arthroplasty surgical approach on postoperative gait mechanics. J Arthroplasty (6 Suppl) 2011; 26: 66-71.

- Rodriguez JA, Deshmukh AJ, Rathod PA, Greiz ML, Deshmane PP, Hepinstall MS, Ranawat AS. Does the direct anterior approach in THA offer faster rehabilitation and comparable safety to the posterior approach? Clin Orthop 2014: (472) (2): 455-63.

- Rolfson O, Rothwell A, Sedrakyan A, Chenok KE, Bohm E, Bozic KJ, Garellick G. Use of patient-reported outcomes in the context of different levels of data. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 3) 2011; 93: 66-71.

- Shaw JA. Experience with a modified posterior approach to the hip joint. A technical note. J Arthroplasty 1991; 6 (1): 11-8.

- Smith AJ, Wylde V, Berstock JR, Maclean AD, Blom AW. Surgical approach and patient-reported outcomes after total hip replacement. Hip Int 2012; 22 (4): 355-61.

- Smith-Petersen MN. Approach to and exposure of the hip joint for mold arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1949; 31 (1): 40-6.

- Spaans AJ, van den Hout JA, Bolder SB. High complication rate in the early experience of minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty by the direct anterior approach. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (4): 342-6.

- Watson-Jones R. Fractures of the neck of the femur. Br J -Surg 1936; 23 (92): 787-808.