Abstract

Background and purpose — Perthes’ disease leads to radiographic changes in both the femoral head and the acetabulum. We investigated the inter-observer agreement and reliability of 4 radiographic measurements assessing the acetabular changes.

Patients and methods — We included 123 children with unilateral involvement, femoral head necrosis of more than 50%, and age at diagnosis of 6 years or older. Radiographs were taken at onset, and 1 year and 5 years after diagnosis. Sharp’s angle, acetabular depth-width ratio (ADR), lateral acetabular inclination (LAI), and acetabular retroversion (ischial spine sign, ISS) were measured by 3 observers. Before measuring, 2 of the observers had a consensus meeting.

Results — We found good agreement and moderate to excellent reliability for Sharp’s angle for all observers (intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) > 0.80 with consensus, ICC = 0.46–0.57 without consensus). There was good agreement and substantial reliability for ADR between the observers who had had a consensus meeting (ICC = 0.62–0.89). Low levels of agreement and poor reliability were found for observers who had not had a consensus meeting. LAI showed fair agreement throughout the course of the disease (kappa = 0.28–0.52). The agreement between observations for ISS ranged from fair to good (kappa = 0.20–0.76).

Interpretation — Sharp’s angle showed the highest reliability and agreement throughout the course of the disease. ADR was only reliable and showed good agreement between the observers when landmarks were clarified before measuring the radiographs. Thus, we recommend both parameters in clinical practice, provided a consensus is established for ADR. The observations for LAI had only fair agreement and ISS showed inconclusive agreement in our study. Thus, LAI and ISS can hardly be recommended in clinical practice.

Perthes’ disease leads to typical radiographic changes of the femoral head. Several authors have described simultaneous changes of the acetabular anatomy, such as hypertrophy, bicompartmental development, retroversion, and dysplastic changes (Yngve and Roberts Citation1985, Joseph Citation1989, Ezoe et al. Citation2006).

Most measurements describing the radiographic changes of the acetabulum on anteroposterior (AP) pelvic radiographs have been validated in children with hip dysplasia. As the hip pathology and the morphological changes in Perthes’ disease are different from those in hip dysplasia, we wanted to assess inter-observer reliability and agreement of 4 commonly used acetabular measurements at the different stages of skeletal maturity in Perthes’ disease.

Patients and methods

In the Norwegian prospective multicenter study on Perthes’ disease, 425 patients were registered between 1996 and 2000 (Wiig et al. Citation2008). Radiographs were taken at onset, and at 1 and 5 years after diagnosis. Based on AP and Lauenstein projections, the affected hips were classified according to the original Catterall classification (1971). For the present study, we included all patients with more than 50% femoral head necrosis (groups 3 and 4), unilateral involvement, and age at onset of 6 years or older (n = 152). We analyzed affected and unaffected hips only if acetabular landmarks were adequately exposed. Thus, another 29 children had to be excluded. The mean age at time of diagnosis of the remaining 123 cases was 7.5 years (SD 1.2) (90 boys and 33 girls).

4 different radiographic parameters were measured on AP pelvic radiographs to assess the acetabular anatomy:

Sharp’s angle

This angle was described by Sharp (Citation1961) in the assessment of hip dysplasia. A reference line was drawn between the inferior points of the teardrops on AP pelvic radiographs. The angle was formed by this reference line and a line connecting the inferior point of the teardrop and lateral edge of the acetabulum (). The angle was measured in the affected and the unaffected hip.

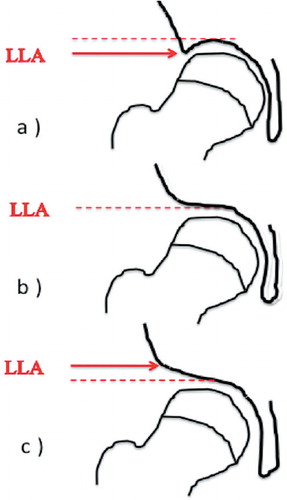

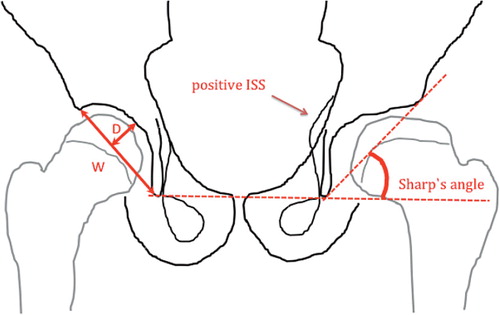

Figure 1. Drawing of an anteroposterior view of the pelvis showing left hip with Perthes’ disease and the right hip unaffected. Sharp’s angle is illustrated on the left hip. The prominence of the ischial spine on the left side is a positive ischial spine sign (ISS). On the right unaffected hip, W shows acetabular width and D shows acetabular depth. Acetabular depth-width ratio is defined as (depth/width) × 1,000.

Acetabular depth-width ratio (ADR)

The acetabular depth and width were measured on AP pelvic radiographs as described by Heyman and Herndon (Citation1950). The width was defined as a line connecting the upper osseous acetabular margin and the lower end of the teardrop. This landmark is often more accurately defined than the lower acetabular margin. The depth was defined as the distance from the width line to the deepest point of the acetabulum (). For this measurement, 1 additional patient had to be excluded because of unsatisfactory exposure of the fossa acetabuli, due to a radiographic shielding device. We defined the ADR according to Cooperman et al. (Citation1983) as (depth/width) × 1,000.

Lateral acetabular inclination

The lateral acetabular inclination was introduced by Cooperman et al. (Citation1983) and later applied by Grzegorzewski et al. (Citation2006) to children with Perthes’ disease. It was defined as down, horizontal, or up depending on whether the lateral lip of the acetabulum was below the weight-bearing dome of the acetabulum, horizontal, or above the weight-bearing dome of the acetabulum ().

Acetabular retroversion

When the ischial spine is visible inside the pelvic inlet on a standardized AP pelvic radiograph, there is a prominence of the ischial spine. This may indicate acetabular retroversion. This sign has been suggested as an alternative measurement of acetabular retroversion to the more commonly used crossover sign in skeletally immature patients (Kalberer et al. Citation2008). We considered the ischial spine sign (ISS) to be positive if the ischial spine protruded beyond the pelvic rim into the pelvic inlet on standardized AP radiographs.

We considered radiographs to be standardized if they met the criteria for symmetric pelvic rotation as outlined by Siebenrock et al. (Citation2003). These are symmetric appearance of the obturator foramina and the tip of the coccyx pointing toward the symphysis pubis.

The measurements were performed manually by 3 observers using a standardized goniometer. None of the radiographs contained any informative landmarks. All measurements were performed independently.

Observer 1 (SH): A resident in orthopedic surgery with special interest in pediatric orthopedic surgery. He assessed all radiographs at onset, and 1 and 5 years after diagnosis (n = 369) (). The observer was briefed on the theoretical basis and practical use of the radiographic parameters in a consensus-building meeting by a consultant in pediatric orthopedic surgery (OW) before measuring the radiographs.

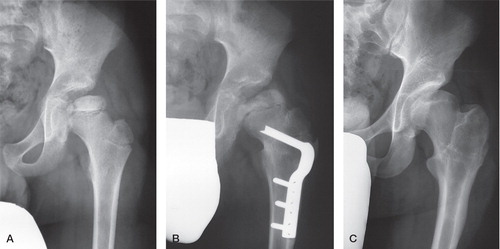

Figure 3. A boy (9.5 years of age at diagnosis) with unilateral Perthes’ disease on the left side. The radiographs were taken at onset (A), at 1-year follow-up (B), and at 5-year follow-up (C). Measurements for the affected hip are given below.

Observer 2 (OW): A consultant in pediatric orthopedic surgery. He measured the AP pelvic radiographs of 57 patients at the time of diagnosis, and at 1 and 5-year follow-up (n = 171). The radiographs of every other patient (alphabetically) were selected (total n = 61). The radiographic films of 4 patients from 3 local hospitals could not be retrieved for the assessment by observer 2; thus, 57 patients were examined.

Observer 3 (SS): A consultant in orthopedic surgery with great experience in examining radiographs of hips in children. He assessed Sharp’s angle (n = 123) and acetabular depth and width (n =122) in radiographs taken 5 years after diagnosis.

Statistics

Several statistical strategies have been described in the evaluation of reproducibility in measurement studies for numerical data (Bland and Altman Citation1986, Citation1999, Petrie Citation2006). The term reproducibility includes both agreement and reliability, and these 2 terms are often used interchangeably (Guyatt et al. Citation1987, Stratford and Goldsmith Citation1997, de Vet et al. Citation2006, Lee et al. Citation2012). Reliability parameters (e.g. intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs)) are related to how well measurements can be distinguished from each other, while agreement parameters, as used in the Bland-Altman method (1986), assess how close scores for repeated measurements are. We analyzed ICC using a 1-way random-effect model assuming a single measurement (McGraw and Wong Citation1996). An ICC of 0 indicates no more reliability than would be expected by chance alone, whereas values close to 1 indicate perfect reliability. We interpreted the intermediate values according to Landis and Koch (Citation1977): values of less than 0.01 indicate poor reliability; 0.01 to 0.20, slight reliability; 0.21 to 0.40, fair reliability; 0.41 to 0.60, moderate reliability; 0.61 to 0.80, substantial reliability; and more than 0.80, excellent reliability.

We used the Bland-Altman method to examine the differences in numerical data between observers (Bland and Altman Citation1986, Citation1999). We calculated the differences between observations of 2 observers for each individual and calculated the mean and the standard deviation of the difference distribution. We defined good agreement to be when mean differences between the observers were less than 5% of their respective mean values. The 95% limits of agreement were calculated as the mean difference between the 2 measurements ± 1.96 SD. This range includes 95% of the inter-observer differences.

The categorical data were analyzed with kappa statistics (Cohen Citation1968). For analysis with 3 or more selected categories, kappa statistics with linear weighting was used, defining the imputed relative distances between ordinal categories as 1. Like the ICC for continuous data, kappa is a measure of agreement between 2 sets of categorical data (Fleiss and Cohen Citation1973). Kappa has a maximum of 1 when agreement is perfect and a value of 0 indicates agreement no better than chance. As suggested by Altmann (1999), we interpreted the kappa values as follows: values of less than 0.20 indicate poor agreement; 0.21 to 0.40, fair agreement; 0.41 to 0.60, moderate agreement; 0.61 to 0.80, good agreement; and greater than 0.80, very good agreement. The multirater kappa statistics are commonly used to describe chance-corrected agreement (Landis and Koch Citation1977, Posner et al. Citation1990, McHugh Citation2012). Statistical analysis was done using SPSS software version 20.

Ethics

Recruitment of patients was done by obtaining informed consent, and the study was approved by the Norwegian Data Inspectorate and the Norwegian Directorate of Health and Social Affairs in 1995.

Results

Sharp’s angle

As measured by observer SH, the mean value of Sharp’s angle at the time of diagnosis was 45° for the affected hip () and it remained stationary during follow-up. The mean angle decreased statistically significantly in normal hips from 45° at diagnosis to 42° at 5-year follow-up (p < 0.01) ().

Table 1. Inter-observer measurements of Sharp’s angle

Observers SH and OW assessed radiographs of 57 patients at the time of diagnosis and at 1- and 5-year follow-up. There were low inter-observer differences between each pair of observations for radiographs taken at diagnosis and at 1- and 5-year follow-up, indicating good agreement in both the affected and unaffected hips (). The range, which included 95% of the inter-observer differences, was narrow and showed negligible differences between radiographs taken at diagnosis and at 1- and 5-year follow-up, and between normal and affected hips. Excellent inter-observer reliability was found for the affected hips (ICC > 0.80), whereas substantial to excellent agreement was noted for normal hips (ICC = 0.65–0.88).

Observers SH and SS measured all radiographs at the 5-year follow-up (n = 123). The mean value for the affected hip was 46° for SH and 44° for SS (), whereas lower mean values were found for the normal hip, at 42° (SH) and 44° (SS).

Using the Bland-Altman method, we found that mean differences between the observers were below 5% of their mean values, indicating good inter-observer agreement. For both the affected hip and the unaffected hip, moderate reliability was found with ICC values ranging from 0.52 to 0.57 ().

OW and SS assessed 57 radiographs 5 years after diagnosis. The mean Sharp’s angle of the affected hip was 46° for OW and 44° for SS. Lower mean values were found for the unaffected hip, at 42° (OW) and 44° (SS) (). The inter-observer agreement between OW and SS was good, with low differences between each pair of measurements and mean differences below 5% of their mean values. The 95% limits of agreement had a wider range but were still acceptable, indicating good agreement. The inter-observer reliability was moderate (ICC = 0.46–0.57).

Acetabular depth-width ratio (ADR)

Observer SH found a mean ADR of 284 in affected hips at the time of diagnosis and significantly lower ADR values 1 and 5 years after diagnosis (262 and 263) (). We observed higher ADR values for the unaffected hip, and they remained unchanged throughout the course of the disease.

Table 2. Inter-observer measurements of ADR

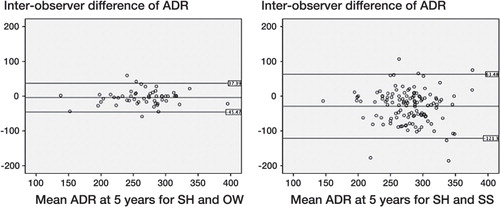

Low inter-observer differences between SH and OW were noted for affected hips and unaffected hips (). The 95% limits of agreement were widest for measurements performed 1 year after diagnosis, compared to the measurements taken at the time of diagnosis and at the 5-year follow-up. We found substantial to excellent reliability with ICC ranging from 0.62 to 0.89 for measurements of the affected hip, whereas moderate to substantial reliability was found for the unaffected hip (ICC = 0.56–0.74) ().

Observers SH and SS assessed 122 radiographs taken at the 5-year follow-up (). The mean differences between the observations exceeded 10% of their mean values and the 95% limits of agreement were rather wide (), indicating poor inter-observer agreement. Similarly, we found only fair reliability between the observers, with ICC = 0.31 for affected hips and ICC = 0.23 for unaffected hips ().

Figure 4. Bland-Altman plot for inter-observer measurements of ADR on the affected hip 5 years after diagnosis. A. Inter-observer agreement between observers with consensus meeting before the measurements (SH and OW). B. Agreement between non-consensus observers (SH and SS).

Inter-observer differences between observers OW and SS (n = 56) were higher for both affected and unaffected hips. The 95% limits of agreement showed wide measurement distribution, indicating lower levels of agreement. Poor reliability was found for unaffected hips (ICC = 0.05) and fair reliability was found for affected hips (ICC = 0.37) ().

Lateral acetabular inclination

We found fair to moderate agreement between observers SH and OW (n = 57) for the affected hip, with kappa values increasing slightly from 0.40 at the time of diagnosis to 0.46 at the 5-year follow-up (). Similarly, we obtained fair to moderate agreement in the unaffected hips, with kappa values ranging from 0.28 to 0.52

Table 3. Inter-observer agreement for lateral acetabular inclination

Acetabular retroversion

29 radiographs that met the criteria for symmetric pelvic rotation at the time of diagnosis were assessed. We found moderate agreement between observers SH and OW for the affected hips (kappa = 0.52, CI: 0.22–0.82) and fair agreement for unaffected hips (kappa = 0.20, CI: 0–0.65). At the 1-year follow-up, 17 radiographs met the criteria for symmetric rotation. We found good inter-observer agreement for the affected side (kappa = 0.76, CI: 0.46–1), whereas fair agreement was obtained for unaffected hips (kappa = 0.26, CI: 0–0.89). At the 5-year follow-up, 20 radiographs met the criteria for symmetric rotation and we found good inter-observer agreement for the affected side (kappa = 0.79, CI: 0.53–1). We found moderate agreement for the normal hips (kappa = 0.49, CI: 0–0.98).

Discussion

In order to describe the acetabular changes in Perthes’ disease properly, there is a need for reliable radiographic measurements that should be easy to use, have good inter- and intra-rater agreement, and have prognostic value.

As part of the Norwegian national prospective study on Perthes’ disease, we have assessed the inter-observer agreement and reliability of 4 commonly used acetabular measurements in children with age at disease onset of 6 years or more, and more than 50% femoral head necrosis (Van den Bogaert et al. Citation1999). This multicenter study involved 28 hospitals throughout Norway and we were not able to standardize the radiographs, which is an obvious limitation of the study.

Radiographic classifications in Perthes’ disease have been subject to validation in previous studies (Mahadeva et al. Citation2010); however, only a few authors have reported on inter-observer agreement and reliability of radiographic measurements in this condition (Wiig et al. Citation2002).

Sharp’s angle

To our knowledge, Sharp’s angle has never been validated in children with Perthes’ disease. Nelitz et al. (Citation1999) reported substantial inter-observer reliability for Sharp’s angle (ICC = 0-74–0.78) in skeletally mature patients with DDH. These results were similar to those of Engesæter et al. (Citation2012), who obtained excellent inter-observer reliability (ICC = 0.83) in 18- to 19-year-old healthy women. Furthermore, Engesæter et al. reported mean differences for each pair of observations of between 2.0% and 7.2% of the mean values and narrow 95% limits of agreement, indicating good agreement. Agus et al. (Citation2002) found that Sharp’s angle was a reliable measurement in skeletally immature children with DDH (mean age 9.5 years). Our inter-observer findings are in accordance with those of previous authors, as we could demonstrate good inter-observer reliability as well as good agreement.

Acetabular depth-width ratio (ADR)

Heyman and Herndon (Citation1950) showed that acetabular width and depth were altered in Perthes’ disease. They defined that the acetabular depth-width ratio is one of the major criteria describing characteristic radiological changes. To our knowledge, no validation of this parameter in Perthes’ disease has been published. However, some authors have assessed the inter-observer reliability and agreement in children with DDH, but the findings differed widely. Takatori et al. (Citation2010) reported large values for the coefficient of variation for ADR, indicating a low degree of agreement, which was in accordance with the results of Clohisy et al. (Citation2009) who demonstrated fair reliability for acetabular depth in adults. In contrast, Nelitz et al. (Citation1999) found moderate inter-observer reliability for ADR with ICC values ranging from 0.58 to 0.63. Engesæter et al. (Citation2012) showed substantial inter-observer reliability for ADR (ICC = 0.77) in patients with DDH. Both publications reported good inter-observer agreement.

In the present study, observers who had a consensus-building meeting before performing the measurements had low differences between each pair of observations and a narrow range of 95% limits of agreement, indicating good inter-observer agreement. ICC values ranged from 0.62 to 0.89, indicating substantial to excellent reliability. In contrast to this, we found a wide range for the 95% limits of agreement and higher differences between the observations for observers without a consensus-building meeting, indicating poorer inter-observer agreement. ICC values for non-consensus observers ranged from 0.07 to 0.37, indicating poor to fair reliability of ADR.

Lateral acetabular inclination

To our knowledge, no previous study has assessed the inter-observer reliability and agreement of this parameter. We found fair to moderate agreement between observers (kappa = 0.28–0.51) in both affected and unaffected hips regardless of when the measurements were performed during the course of the disease. Based on our findings, acetabular inclination appears to be less suitable in radiographic evaluation of Perthes’ disease.

Acetabular retroversion

Assessment of the anatomy of a 3-dimensional object such as the acetabulum on a 2-dimensional radiograph has obvious limitations. However, the crossover sign (Jamali et al. Citation2007) and the ISS (Kalberer et al. Citation2008) revealed acetabular retroversion in AP pelvic radiographs. Of the 57 radiographs that were available to inter-observer analysis, 28 radiographs had to be excluded at time of diagnosis, 40 at 1-year follow-up, and 37 at 5-year follow-up due to radiographic standardization criteria. Perthes’ disease leads to muscular atrophy and contracture of the affected side, which may cause pelvic rotation along the longitudinal axis on AP pelvic radiographs (Schiller and Axer Citation1972). This might be the reason for the high number of dropouts in our study population. Other authors who assessed acetabular retroversion in Perthes’ disease had a similar reduction of radiographs included (Larson et al. Citation2011, Kawahara et al. Citation2012). To our knowledge, only 1 study so far has assessed the inter-observer agreement of acetabular retroversion using ISS (Kappe et al. Citation2011). The authors examined AP pelvic radiographs of 20 skeletally mature patients and the number of patients included was similar to the number of radiographs assessed at diagnosis, and at 1-year and 5-year follow-up in our study. Kappe et al. (Citation2011) emphasized that acetabular version was subject to considerable inter-observer differences and related to the individual experience of observers. Our findings are in accordance with these results, as we had moderate to good inter-observer agreement for affected hips but only fair to moderate inter-observer agreement for unaffected hips. This indicates that acetabular retroversion as assessed on pelvic radiographs is hardly a suitable parameter in Perthes’ disease.

In conclusion, Sharp’s angle had the highest inter-observer reliability and agreement of the 4 parameters investigated—throughout the course of Perthes’ disease in skeletally immature patients. ADR was reliable and showed good agreement between the observers only when landmarks were clarified before measuring the radiographs. Thus, we recommend both parameters in clinical practice, provided a common consensus is established and that these parameters are of prognostic value, which will be evaluated in a separate study. The observations for lateral inclination of the acetabulum had only fair to moderate agreement and ISS showed inconclusive agreement in our study. Thus, these parameters can hardly be recommended in clinical practice.

SH: data collection, radiographic and statistical analysis, writing, and manuscript preparation. SS: data collection and radiographic analysis. AHP: statistical analysis and evaluation. TT: planning of the study and manuscript preparation. OW: planning of the study, data collection, radiographic analysis, and manuscript preparation.

No competing interests declared.

Notes

- Agus H, Bicimoglu A, Omeroglu H, Tumer Y. How should the acetabular angle of sharp be measured on a pelvic radiograph? J Pediatr Orthop 2002; 22 (2): 228-31.

- Altmann DB. Practical statistics for medical research. Chapman & Hall, London 1999.

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986; 1 (8476): 307-10.

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Measuring agreement in method comparison studies. Stat Methods Med Res 1999; 8 (2): 135-60.

- Catterall A. The natural history of perthes’ disease. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1971; 53 (1): 37-53.

- Clohisy JC, Carlisle JC, Trousdale R, Kim YJ, Beaule PE, Morgan P, et al. Radiographic evaluation of the hip has limited reliability. Clin Orthop 2009; (467) (3): 666-75.

- Cohen J. Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull 1968; 70 (4): 213-20.

- Cooperman DR, Wallensten R, Stulberg SD. Acetabular dysplasia in the adult. Clin Orthop 1983; (175): 79-85.

- de Vet HC, Terwee CB, Knol DL, Bouter LM. When to use agreement versus reliability measures. J Clin Epidemiol 2006; 59 (10): 1033-9.

- Engesaeter IO, Laborie LB, Lehmann TG, Sera F, Fevang J, Pedersen D, et al. Radiological findings for hip dysplasia at skeletal maturity. Validation of digital and manual measurement techniques. Skeletal Radiol 2012; 41 (7): 775-85.

- Ezoe M, Naito M, Inoue T. The prevalence of acetabular retroversion among various disorders of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006; 88 (2): 372-9.

- Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. Educational and Psychological Measurement 1973; 33 (3): 613-9.

- Grzegorzewski A, Synder M, Kozlowski P, Szymczak W, Bowen RJ. The role of the acetabulum in perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop 2006; 26 (3): 316-21.

- Guyatt G, Walter S, Norman G. Measuring change over time: Assessing the usefulness of evaluative instruments. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40 (2): 171-8.

- Heyman CH, Herndon CH. Legg-perthes disease; a method for the measurement of the roentgenographic result. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1950; 32 (4): 767-78.

- Jamali AA, Mladenov K, Meyer DC, Martinez A, Beck M, Ganz R, et al. Anteroposterior pelvic radiographs to assess acetabular retroversion: High validity of the “cross-over-sign”. J Orthop Res 2007; 25 (6): 758-65.

- Joseph B. Morphological changes in the acetabulum in perthes’ disease. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1989; 71 (5): 756-63.

- Kalberer F, Sierra RJ, Madan SS, Ganz R, Leunig M. Ischial spine projection into the pelvis : A new sign for acetabular retroversion. Clin Orthop 2008; (466) (3): 677-83.

- Kappe T, Kocak T, Neuerburg C, Lippacher S, Bieger R, Reichel H. Reliability of radiographic signs for acetabular retroversion. Int Orthop 2011; 35 (6): 817-21.

- Kawahara S, Nakashima Y, Oketani H, Wada A, Fujii M, Yamamoto T, et al. High prevalence of acetabular retroversion in both affected and unaffected hips after legg-calve-perthes disease. J Orthop Sci 2012; 17 (3): 226-32.

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33 (1): 159-74.

- Larson AN, Stans AA, Sierra RJ. Ischial spine sign reveals acetabular retroversion in legg-calve-perthes disease. Clin Orthop 2011; 469 (7): 2012-8.

- Lee KM, Lee J, Chung CY, Ahn S, Sung KH, Kim TW, et al. Pitfalls and important issues in testing reliability using intraclass correlation coefficients in orthopaedic research. Clin Orthop Surg 2012; 4 (2): 149-55.

- Mahadeva D, Chong M, Langton DJ, Turner AM. Reliability and reproducibility of classification systems for legg-calve-perthes disease: A systematic review of the literature. Acta Orthop Belg 2010; 76 (1): 48-57.

- McGraw KO, Wong SP. Forming interferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol Methods 1996; 1 (1): 30-46.

- McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2012; 22 (3): 276-82.

- Nelitz M, Guenther KP, Gunkel S, Puhl W. Reliability of radiological measurements in the assessment of hip dysplasia in adults. Br J Radiol 1999; 72 (856): 331-4.

- Petrie A. Statistics in orthopaedic papers. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006; 88 (9): 1121-36.

- Posner KL, Sampson PD, Caplan RA, Ward RJ, Cheney FW. Measuring interrater reliability among multiple raters: An example of methods for nominal data. Stat Med 1990; 9 (9): 1103-15.

- Schiller MG, Axer A. Legg-calve-perthes syndrome (l.C.P.S.). A critical analysis of roentgenographic measurements. Clin Orthop 1972; (86): 34-42.

- Sharp IK. Acetabular dysplasia–the acetabular angle. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1961; 43: 268- 72.

- Siebenrock KA, Kalbermatten DF, Ganz R. Effect of pelvic tilt on acetabular retroversion: A study of pelves from cadavers. Clin Orthop 2003; (407): 241-8.

- Stratford PW, Goldsmith CH. Use of the standard error as a reliability index of interest: An applied example using elbow flexor strength data. Phys Ther 1997; 77 (7): 745-50.

- Takatori Y, Ito K, Sofue M, Hirota Y, Itoman M, Matsumoto T, et al. Analysis of interobserver reliability for radiographic staging of coxarthrosis and indexes of acetabular dysplasia: A preliminary study. J Orthop Sci 2010; 15 (1): 14-9.

- Van den Bogaert G, de Rosa E, Moens P, Fabry G, Dimeglio A. Bilateral legg-calve-perthes disease: Different from unilateral disease? J Pediatr Orthop B 1999; 8 (3): 165-8.

- Wiig O, Terjesen T, Svenningsen S. Inter-observer reliability of radiographic classifications and measurements in the assessment of perthes’ disease. Acta Orthop Scand 2002; 73 (5): 523-30.

- Wiig O, Terjesen T, Svenningsen S. Prognostic factors and outcome of treatment in perthes’ disease: A prospective study of 368 patients with five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008; 90 (10): 1364-71.

- Yngve DA, Roberts JM. Acetabular hypertrophy in legg-calve-perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop 1985; 5 (4): 416-21.