Abstract

Background and purpose — Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is important for detecting extracapsular pseudotumors, but there is little information on the accuracy of MRI and appropriate intervals for repeated imaging. We evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of MRI for detecting pseudotumors in 155 patients (167 hips) with metal-on-metal (MoM) hip arthroplasties that failed due to adverse reactions to metal debris (ARMD).

Methods — Preoperative MRIs were performed with two 1.5 T MRI scanners and graded by a senior musculoskeletal radiologist using a previously described MRI pseudotumor grading system. Revision findings were retrieved from surgical notes, and pseudotumors were retrospectively graded as fluid-filled, mixed-type, or solid.

Results — The sensitivity of MRI was 71% and the specificity was 87% for detecting extracapsular pseudotumors. The sensitivity was 88% (95% CI: 70–96) when MRI was performed less than 3 months before the revision surgery. Interestingly, when the time that elapsed between MRI and revision was more than 1 year, the sensitivity calculated was only 29% (95% CI: 14–56). Comparison between MRI and revision classifications gave moderate agreement (Cohen’s kappa = 0.4).

Interpretation — A recent MRI predicts the presence of a pseudotumor well, but there is more discrepancy when the MRI examination is over a year old, most likely due to the formation of new pseudotumors. 1 year could be a justifiable limit for considering a new MRI if development of ARMD is suspected. MRI images over a year old should not be used in decision making or in planning of revision surgery for MoM hips.

Metal-on-metal (MoM) hip replacements have been widely used for the treatment of hip osteoarthritis, particularly in young and active patients (Bozic et al. Citation2009). During the last few years, an increased risk of developing soft tissue reactions linked to increased wear of MoM articulation has been reported (CitationPandit et al. 2008, Kwon et al. Citation2010, Langton et al. Citation2011). An umbrella term “adverse reaction to metal debris” (ARMD) has been used to describe these tissue reactions, which include metallosis, aseptic lymphocytic vasculitis-associated lesions, and the fluid-filled or solid extracapsular lesions often referred to as pseudotumors (Langton et al. Citation2011). Most patients have high blood metal ions and many experience pain in the groin and thigh region, but ARMD may also be found in patients presenting with no clinical symptoms and normal whole-blood metal ion levels (Hart et al. Citation2011, Wynn-Jones et al. Citation2011). Asymptomatic extracapsular pseudotumors have been reported to increase and decrease in size with occasional remission of small masses, and they may involve the abductor and iliopsoas muscles (Almousa et al. Citation2013). Revision surgeries because of pseudotumors have been reported to have significantly poorer outcome than hip revisions for other reasons (Grammatopolous et al. Citation2009). Imaging is therefore needed to identify these patients for closer follow-up or revision surgery. Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also of importance for surgeons to visualize the location and dimensions of the pseudotumor for optimal resection (Liddle et al. Citation2013).

MRI and ultrasonography are the main imaging modalities for assessment of ARMD lesions. Modern MRI techniques allow good visibility in the hip region, even though intracapsular lesions cannot be reliably assessed in some cases due to metal artifacts. To our knowledge, only 1 study has compared pseudotumors seen in MRI with those actually found in revision surgery (Liddle et al. Citation2013).

The main aim of this study was to evaluate the ability of preoperative MRI to detect extracapsular pseudotumors encountered in revision surgery and to assess appropriate intervals for repeated imaging, when development/progression of soft tissue pathologies is suspected. A secondary aim was to ascertain whether pseudotumors fall into the same categories in both MRI and revision surgery classifications.

Patients and methods

Study population

DePuy Orthopaedics (Warsaw, IN) voluntarily recalled the Articular Surface Replacement (ASR) MoM hip system in August 2010, and the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) announced a medical device alert regarding ASR hip replacements in September 2010 (CitationMHRA 2010). After this announcement, we established a mass screening program to identify possible articulation-related complications in patients who had received either ASR hip resurfacing (HR) or ASR XL total hip replacement (THR) at our institution. All the patients attending the screening received an Oxford hip score (OHS) questionnaire, underwent a clinical examination at our outpatient clinic, and were referred for measurement of whole-blood cobalt and chromium levels; hip radiographs were taken before each visit. Furthermore, all the patients were also referred for MR imaging, performed using MRI parameters designed to limit metal artifacts. If MRI was contraindicated or could not be done due to patient-related factors (such as claustrophobia), the patient was referred for ultrasound (US) examination of the affected hip.

ASR MoM hip replacements had been used in 1,036 operations (887 patients) at our institution between March 2004 and December 2009. ASR HR was used for 498 hips and ASR THR for 538 hips. At the time of writing, 232 hips (22%) in 218 patients have been revised at our institution, most (n = 211, 91%) of them due to ARMD. Preoperative MR imaging was performed on 158 patients (170 hips) with a perioperatively confirmed diagnosis of ARMD, and 98% of these patients agreed to participate in this study (155 patients, 167 hips). There were no patients with US performed before MRI. According to previously described criteria (Reito et al. Citation2013), failure was classified to be secondary to ARMD if metallosis, macroscopic synovitis, and/or extracapsular pseudotumors were found during revision and/or a moderate to high number of perivascular lymphocytes along with tissue necrosis and/or fibrin deposition was seen in the histopathological sample. Component loosening and periprosthetic fracture had to be ruled out clinically and radiographically in order to set a diagnosis of ARMD. Infection was ruled out if all (at least 5) culture results were negative from samples obtained during revision surgery.

MRI evaluation

MRIs were performed with two 1.5 T scanners (Siemens Magnetom Avanto; Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany and GE Signa HD; General Electric Healthcare, WI). Scanners were adjusted to produce minimal metal artifacts. Sequences used in imaging were coronal and axial T1-weighted fast spin echo (FSE) and coronal, axial, and sagittal short tau inversion recovery (STIR).

MR images were originally graded prospectively by 3 senior musculoskeletal radiologists who used the classification by Anderson et al. (Citation2011). All MRIs were subsequently re-graded retrospectively using the MRI pseudotumor grading published by Hart et al. (Citation2012). This grading is based on MRI signal appearance of extra-articular findings. Re-grading of MR images was performed by a senior musculoskeletal radiologist with 7 years of experience who was blind regarding the perioperative findings. Hips without extra-articular findings were classified as class 0. All abnormal extracapsular cystic or mass lesions with or without connection to the joint capsule were considered to be pseudotumors. Class 1 included hips with a thin-walled fluid-filled pseudotumor, 2a was a fluid-filled pseudotumor with thick or irregular walls, and 2b was a pseudotumor with thick or irregular walls and atypical signal from contents. A class 3 finding was a solid pseudotumor. The grading system used did not include the location of pseudotumors, so we did not evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of MRI on trochanteric and iliopsoas region pseudotumors separately.

All revisions were performed by – or under the direct supervision of – 5 surgeons with 12, 19, 20, 21, and 21 years of experience of hip replacement surgery. Revision was considered if there was a type 2b or type 3 pseudotumor seen in cross-sectional imaging regardless of symptoms or metal ion levels, or if the patient had symptomatic hip and elevated metal ion levels even with normal cross-sectional imaging, or a continuously symptomatic hip regardless of imaging findings or metal ion levels. Pseudotumor was defined as a distinct extracapsular cystic or solid mass with variable connection to the joint. Pseudotumors seen in revision surgery were retrospectively graded as fluid-filled, solid, or mixed-type based on the surgeon’s description of consistency, wall thickness, and content of pseudotumors (). Descriptions were retrieved from surgical notes. Cystic lesions were graded as fluid-filled pseudotumor. Lesions with only minor or no fluid-like component were graded as solid pseudotumors. Mixed-type was defined as being mainly fluid-filled, but also having thick or irregular walls and solid contents. If there were several pseudotumors, grading was based on complexity of the lesion containing the most solid components.

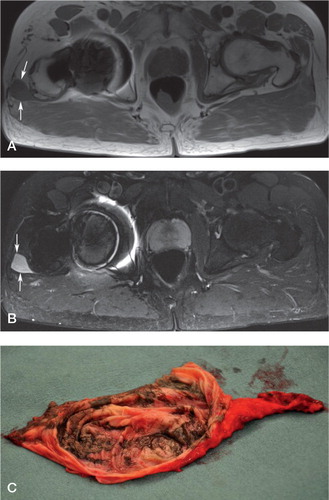

Figure 1. Images from a 70-year-old man who had undergone total hip arthroplasty of the right hip 3.4 years earlier. He had a tingling sensation in the trochanteric region and the replaced right hip made clacking sounds. Whole-blood metal ion levels were slightly elevated (cobalt 7.5 ppb and chromium 5.8 ppb; normal reference values are < 0.8 ppb for Co and Cr). Axial view of a thin-walled cystic pseudotumor in the greater trochanteric region (arrows) with fluid-like low signal intensity in T1 (panel A) and high in STIR (B). A thin-walled and fluid-filled pseudotumor with metal staining was encountered at revision surgery (C).

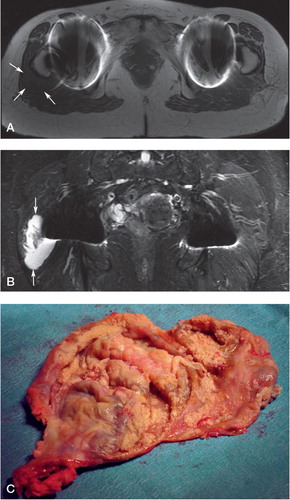

Figure 2. Images from a 64-year-old woman who had undergone total hip arthroplasty of the right hip 4.7 years earlier. She had stiffness and exercise-related pain in the replaced right hip. Whole-blood cobalt was 6.9 ppb and chromium was 4.8 ppb (normal reference values are < 0.8 ppb for Co and Cr). A thick-walled pseudotumor with solid content was seen extending posterolaterally from the hip joint region on the right side. Variable signal intensity was seen in axial T1 (panel A). Synovial hypertrophy was best seen in coronal STIR view (B). A mixed-type pseudotumor with thick walls and partially solid contents was seen at revision surgery (C).

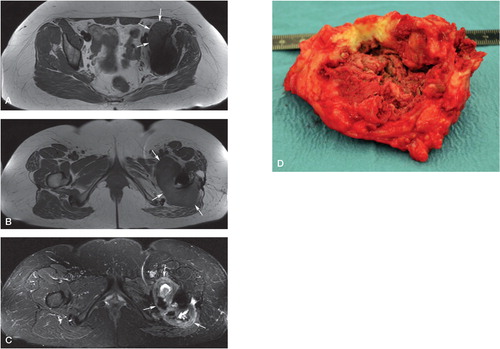

Figure 3. Images from a 43-year-old woman who had undergone total hip arthroplasty of the left hip 2.5 years earlier. Her replaced hip made clacking sounds, and she also had intense pain in both the groin and in the trochanteric region during exercise—and even at rest. Whole-blood cobalt was 8.8 ppb and chromium was 3.1 ppb (normal reference values are < 0.8 ppb for Co and Cr). A. Axial T1 view of a thick-walled partly cystic large pseudotumor mass extending from the iliopsoas region to the posterolateral region. The posterolateral part of the pseudotumor appeared mostly solid with variable signal intensity in T1 (panel B) and STIR (C). A predominantly solid pseudotumor was encountered in revision surgery (D).

Statistics

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for detecting pseudotumors with MRI (CitationHerbert 2013). We assessed the effect of the time elapsed between MRI and revision surgery on the accuracy of MRI by dividing our patients into 4 groups: those for whom 3 months, 3–6 months, 6–12 months, and more than 12 months had elapsed. Sensitivity and specificity were analyzed separately for each time cohort. For the evaluation of differences in classification between MRI and revision surgery, we considered MRI groups 1 and 2a as fluid-filled MRI findings, 2b as mixed-type, and group 3 as solid finding. Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated for comparison of classification in MRI and revision surgery. Bias caused by clustered observations was controlled for by performing the same analyses with all 12 bilateral patients excluded. IBM SPSS Statistics 20 was used for statistical analysis.

Ethics

The institutional review board approved this study (April 27, 2011; R11006) and procedures followed were in accordance with Helsinki Declaration of 1975. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Perioperatively, pseudotumors were found in 98 hips (59%). Of these, 87 were fluid-filled, 2 appeared solid, and 9 were of mixed type. All 167 hips had intracapsular ARMD lesions such as metallosis, synovitis, capsular necrosis, osteolysis, or any combination of these findings ().

Table 1. Demographics

Based on imaging, a pseudotumor was detected in 79 hips (). Preoperative MRI provided a sensitivity of 71% (CI: 62–79) and a specificity of 87% (CI: 77–93) for detecting pseudotumors. Thus, MRI had a positive predictive value of 89% (CI: 80–94) and a negative predictive value of 68% (CI: 58–77). Sensitivity and specificity were similar in the THR group (72% and 89%) and the HR group (68% and 79%). Of the 28 pseudotumors that were not detected by MRI, 27 were fluid-filled and 1 was mixed-type. 9 pseudotumors seen in preoperative MRI were not found during revision surgery.

Table 2. Cross-tabulation of MRI and revision findings

If MRI was performed less than 3 months before revision surgery, it provided a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 78% for detecting pseudotumors (). Sensitivity was substantially lower in a subgroup of patients who had been imaged with MRI more than 1 year before revision surgery (). Of the 28 pseudotumors previously mentioned that were not detected by MRI, 11 had been imaged more than 1 year before revision. 3 fluid-filled pseudotumors found in revision were not seen at MRI performed less than 3 months before revision surgery. Furthermore, 8 fluid-filled pseudotumors were not detected at MRI performed between 3 and 6 months before revision.

Table 3. Effect of time on calculated sensitivity and specificity of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Of the 87 revision surgery-confirmed fluid-filled pseudotumors, 42 were categorized correctly by MRI grading—mixed-type (3 of 9) and solid pseudotumor (1 of 2). Kappa coefficient was 0.40 (indicating moderate agreement). Exclusion of the 12 patients with bilateral MoM hips only resulted in negligible changes in the results, so we considered that bias introduced by clustered observations was insignificant (data not shown).

Discussion

In revision surgery, 98 pseudotumors were found in 167 ASR MoM hips (59%). Almost one-third of these pseudotumors were not detected in preoperative MRI. MRI predicted the presence of pseudotumor in revision surgery well, if it was performed less than 3 months before revision surgery. On the other hand, in the group with more than 1 year between MRI and revision surgery, the discrepancy was far greater. False-negative and false-positive cases involved mostly fluid-filled pseudotumors, which might suggest that the amount of fluid in pseudotumors changes over time. Of the 27 fluid-filled pseudotumors that were not seen at preoperative MRI, only 3 had been imaged less than 3 months before revision surgery.

Several papers have described pseudotumors seen in MRI, in both symptomatic and asymptomatic MoM hips, and the prevalence of pseudotumors has been reported to range between 7% and 69% (Wynn-Jones et al. Citation2011, Chang et al. Citation2012, Hart et al. Citation2012, Hayter et al. Citation2012). To our knowledge, there has only been 1 study in the literature comparing pseudotumors seen in MRI with those actually found at revision surgery (Liddle et al. Citation2013). That study analyzed 39 failed MoM hips and found that MRI provided a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 59% in detecting pseudotumors. The authors stated that small fluid-filled pseudotumors were often seen in preoperative MRI. These lesions were, however, not always considered significant findings in revision surgery, which may partly explain the low specificity reported in that study (59%).

We are aware that the present study had some limitations. At the time of the revisions, no systematic classification of revision pseudotumor findings was available. Thus, we created a classification based on typical surgical findings and the pseudotumors were classified retrospectively on the basis of surgical notes by 5 orthopedic surgeons. With increasing experience of diagnosing and treating patients with ARMD during the study period, it may be that some surgeons described similar lesions differently at different times. This could have affected the category into which the pseudotumor lesion fell. However, we consider that the absence or presence of pseudotumor would have been registered appropriately in the surgical notes, so that it would have no marked effect on the sensitivity and specificity calculated.

Since all the patients in the study had been revised, the number of false-negative MRI findings in asymptomatic patients (who had no need for revision) remains unknown. This may have biased our results, and resulted in the sensitivity appearing better than it actually was. Naturally, the surgeons performing the revisions were not blinded to preoperative MRI findings, and it is therefore possible that the specificity may have been overestimated. However, these weaknesses affecting sensitivity and specificity are mostly unavoidable when the accuracy of a diagnostic test is evaluated using findings in revision surgery as the baseline.

Even though the retrospective methodology would have left room for error when comparing perioperative findings and MRI, we consider our finding of a poor association between > 1-year-old MRI results and surgical findings to be clinically significant. Even in relatively small subgroups, a statistically significant difference was found in the sensitivities calculated between MRI findings that were over a year old and under a year old. That older images would be less reliable is logical, due to the developing nature of ARMD (Ebreo et al. Citation2013), but there is no definite evidence on how long these reactions take to develop. Guidelines recommending imaging of patients with high-risk components and symptomatic patients have been published, but they do not give suggestions on appropriate intervals for imaging (CitationMHRA 2012, CitationFDA 2013). In a recent study involving repeated MRI, Van der Weegen et al. (Citation2013) reported little or no variation in asymptomatic pseudotumors, suggesting that there was little benefit of repeated imaging within 1 year. CitationThomas et al. (2013) also suggested a year as an interval for repeated cross-sectional imaging, based on their experience of development of ARMD taking several years. Our findings support their conclusions.

A recent study found poor intra- and interobserver reliability for the grading used in our study also (van der CitationWeegen et al. 2014). In the present study, the comparison of MRI and revision classifications yielded a moderate kappa coefficient. One-half of fluid-filled pseudotumors, one-third of the mixed-type pseudotumors, and half of the solid pseudotumors were placed in the same category in both MRI and revision classifications. Some of the discrepancy was most likely due to the evolving nature of these lesions. The amount of fluid or solid contents and the thickness of the wall may change with time. A small amount of solid content may go unnoticed, and also the description of wall thickness may be imprecise, thus making the lesion fall into a different category. This is likely to cause misclassification, especially regarding classes 2a, 2b, and 3. An atypical MRI signal in the lesion may represent solid contents, previous bleeding, increased protein content, or the presence of metal particles. In revision, this kind of lesion may appear either cystic or more solid. MRI appearance of the lesion affects the clinical decision making, so it is important to know how well the findings correlate. Currently, class 2b and 3 pseudotumors are considered to be more severe clinically. Further studies are needed to evaluate the clinical outcome of different types of pseudotumors, and the classification of pseudotumors should be developed accordingly.

OL: study design, literature search, data collection and analysis, interpretation of data, statistics, writing and revision of the manuscript, and final approval. PE, AR, JP, TP, and AE: study design, interpretation of data and statistics, writing and revision of the manuscript, and final approval.

We thank Ms Ella Lehto, RN, for maintaining our study database. The study was supported by the competitive research funds of Pirkanmaa Hospital District, Tampere, Finland (grant 9N044, representing governmental funding). The source of funding had no role at any stage of this investigator-initiated study.

JP has a consultant contract with Zimmer. No commercial companies were involved in planning of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript.

- Almousa SA, Greidanus NV, Masri BA, Duncan CP, Garbuz DS. The natural history of inflammatory pseudotumors in asymptomatic patients after metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 2013; (471) (12): 3814-21.

- Anderson H, Toms AP, Cahir JG, Goodwin RW, Wimhurst J, Nolan JF. Grading the severity of soft tissue changes associated with metal-on-metal hip replacements: Reliability of an MR grading system. Skeletal Radiol 2011; 40 (3): 303-7.

- Bozic KJ, Kurtz S, Lau E, Ong K, Chiu V, Vail TP, Rubash HE, Berry DJ. The epidemiology of bearing surface usage in total hip arthroplasty in the united states. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2009; 91 (7): 1614-20.

- Chang EY, McAnally JL, Van Horne JR, Statum S, Wolfson T, Gamst A, Chung CB. Metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: Do symptoms correlate with MR imaging findings? Radiology 2012; 265 (3): 848-57.

- Ebreo D, Bell PJ, Arshad H, Donell ST, Toms A, Nolan JF. Serial magnetic resonance imaging of metal-on-metal total hip replacements. follow-up of a cohort of 28 mm ultima TPS THRs. Bone Joint J 2013; 95-B (8): 1035-9.

- Grammatopolous G, Pandit H, Kwon YM, Gundle R, McLardy-Smith P, Beard DJ, Murray DW, Gill HS. Hip resurfacings revised for inflammatory pseudotumour have a poor outcome. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009; 91 (8): 1019-24.

- Hart AJ, Sabah SA, Bandi AS, Maggiore P, Tarassoli P, Sampson B, A Skinner J. Sensitivity and specificity of blood cobalt and chromium metal ions for predicting failure of metal-on-metal hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011; 93 (10): 1308-13.

- Hart AJ, Satchithananda K, Liddle AD, Sabah SA, McRobbie D, Henckel J, Cobb JP, Skinner JA, Mitchell AW. Pseudotumors in association with well-functioning metal-on-metal hip prostheses: A case-control study using three-dimensional computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2012; 94 (4): 317-25.

- Hayter CL, Gold SL, Koff MF, Perino G, Nawabi DH, Miller TT, Potter HG. MRI findings in painful metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012; 199 (4): 884-93.

- Herbert R. Confidence interval calculator (2013). Available from http://www.pedro.org.au/english/downloads/confidence-interval-calculator/

- Kwon YM, Glyn-Jones S, Simpson DJ, Kamali A, McLardy-Smith P, Gill HS, Murray DW. Analysis of wear of retrieved metal-on-metal hip resurfacing implants revised due to pseudotumours. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010; 92 (3): 356-61.

- Langton DJ, Joyce TJ, Jameson SS, Lord J, Van Orsouw M, Holland JP, Nargol AV, De Smet KA. Adverse reaction to metal debris following hip resurfacing: The influence of component type, orientation and volumetric wear. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011; 93 (2): 164-71.

- Liddle AD, Satchithananda K, Henckel J, Sabah SA, Vipulendran KV, Lewis A, Skinner JA, Mitchell AW, Hart AJ. Revision of metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty in a tertiary center. Acta Orthop 2013; 84 (3): 237-45.

- Medicines and healthcare products regulatory agency (MHRA). (Internet) Medical device alert: All metal-on-metal (MoM) hip replacements (MDA/2010/069). (cited 2013 Dec 27); Available from: http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/dts-bs/documents/medicaldevicealert/con093791.pdf

- Medicines and healthcare products regulatory agency (MHRA). (Internet) Medical device alert: All metal-on-metal (MoM) hip replacements (MDA/2012/036). (cited 2013 Dec 27); Available from: http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/dts-bs/documents/medicaldevicealert/con155767.pdf

- Pandit H, Glyn-Jones S, McLardy-Smith P, Gundle R, Whitwell D, Gibbons CL, Ostlere S, Athanasou N, Gill HS, Murray DW. Pseudotumours associated with metal-on-metal hip resurfacings. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008; 90 (7): 847-51.

- Reito A, Puolakka T, Elo P, Pajamaki J, Eskelinen A. High prevalence of adverse reactions to metal debris in small-headed ASRTM hips. Clin Orthop 2013; (471) (9): 2954-61.

- Thomas MS, Wimhurst JA, Nolan JF, Toms AP. Imaging metal-on-metal hip replacements: The norwich experience. HSS J 2013; 9 (3): 247-56.

- US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (internet) Information for orthopaedic surgeons. (updated 2013 Jan 17; cited 2013 Dec 27); Available from http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ImplantsandProsthetics/MetalonMetalHipImplants/ucm241667.htm

- van der Weegen W, Brakel K, Horn RJ, Hoekstra HJ, Sijbesma T, Pilot P, Nelissen RG. Asymptomatic pseudotumours after metal-on-metal hip resurfacing show little change within one year. Bone Joint J 2013; 95-B (12): 1626-31.

- van der Weegen W, Brakel K, Horn RJ, Wullems JA, Das HP, Pilot P, Nelissen RG. Comparison of different pseudotumor grading systems in a single cohort of metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty patients. Skeletal Radiol 2014; 43 (2): 149-55.

- Wynn-Jones H, Macnair R, Wimhurst J, Chirodian N, Derbyshire B, Toms A, Cahir J. Silent soft tissue pathology is common with a modern metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (3): 301-7.