We present a case of bilateral medial tibia stress syndrome (MTSS) in a 500- to 800-year-old male skeleton with an estimated age at death of between 20 and 30 years. The skeleton came from a Byzantine graveyard in Rhodes, Greece, which was in use between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries AD.

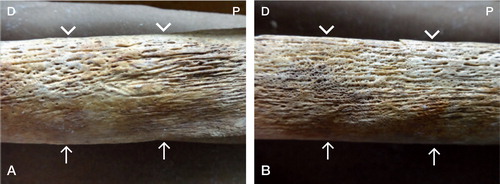

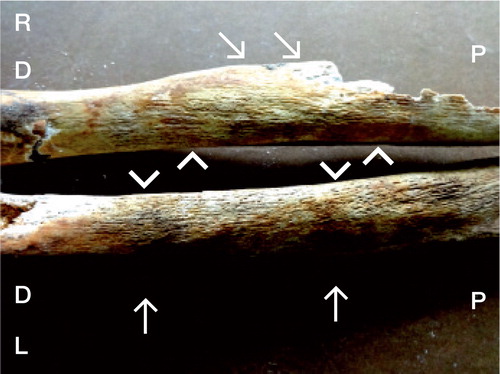

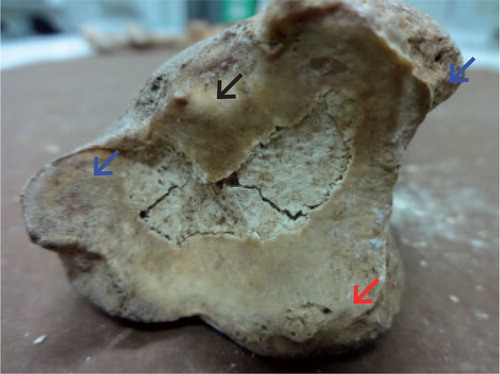

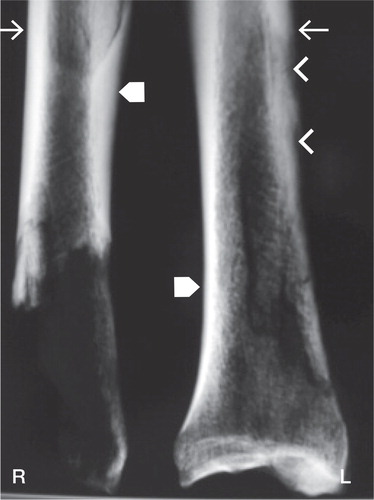

The tibiae exhibit symmetrically developed surface lesions along the posterior-medial aspects involving the middle and distal thirds of diaphyses, in accordance with the pattern of symptom distribution in MTSS. The lesions comprise longitudinal striation and associated pitting, mainly affecting the mid-diaphyses and posterior-medial borders and in finely porous, diffuse tissue predominantly over the distal diaphyses (). Cortical lesions are more prominent in the left tibia while corresponding sites over the right tibia exhibit excessive cortical tissue deposition resulting in an overall robust morphology (). Additionally, there are bilateral focal erosions and osteophytes on distal articular surfaces () (Jurmain and Kilgore Citation1995, Ortner Citation2003). Conventional radiographs confirm the expanded cortical component and disturbed outline along the posterior-medial aspect of the distal left tibia and further reveal the sclerotic distal articular surface, whereas the right tibia shows thickened cortex, markedly increased along the anterior border ().

Figure 1. Medial surface of left tibia, middle third (panel A) and distal third (panel B). Linear arrows show anterior borders and arrowheads show posterior borders. P: proximal end; D: distal end.

Figure 2. Right (R) and left (L) tibiae with lesions distributed over the posterior-medial diaphyseal aspects. The right tibia shows less well developed cortical lesions and differentiated outline consequent to a striking increase in cortical bone. For legends, see Figure 1.

Figure 3. Left tibia: distal articular surface with articular osteophyte (black arrow), marginal osteophytes (blue arrows), and articular surface erosions (red arrow).

Figure 4. Conventional radiograph of right (R) and left (L) distal tibiae. Shown are expanded cortex and irregular outline along the posterior-medial aspect of the left tibia (arrowheads) as well as sclerotic distal articular surface. The right tibia has increased radiodensity corresponding to thickened cortex. Tailed arrows indicate posterior borders and block arrows indicate anterior borders.

Discussion

Indicators of skeletal stress including periosteal striation and osteoarthritis have been assessed in several studies of archaeological populations (Ortner Citation2003). However, to our knowledge, the specific pattern of lesions denoting MTSS has not been reported.

MTSS refers to exercise-induced painful symptoms localized along the posterior-medial aspect of the distal tibia and is a common lower-leg overuse injury distinct from stress fractures and chronic compartment syndrome. The highest incidence is seen in young people with repetitive weight-bearing activities, typically associated with sports and military training (Yates and White Citation2004, Moen et al. Citation2009).

The underlying pathophysiological mechanism is unclear. The “traction-induced injury” theory suggests that tibial periostitis, consequent to traction of the soleus muscle and deep plantar flexors over the periosteum-fascia interface causes the localized pain. In contrast, the bone-bending theory suggests that painful symptoms arise from a stress reaction of bone tissue in response to cyclic loading, mainly involving the distal most strained tibial aspects where newly synthesized tissue is highly porous and sensitive (Yates and White Citation2004, Moen et al. Citation2009).

The skeleton of the young man from medieval Rhodes exhibits tibial bilateral cortical lesions representing periostitis and bone-remodeling changes. Bone striation and vascularization pitting is a periosteal reaction involving deep flexors and soleus muscle-related sites, in accordance with the traction injury theory, whereas finely porous bone deposited over remodeled diaphyseal sites would be a reaction to increased strain, as suggested by the bone-bending theory. It is noteworthy that the lower-leg skeleton exhibits degenerative lesions on the articular surfaces of the ankle joint, a rare site of osteoarthritis (Thomas and Daniels Citation2003), and extensive diaphyseal remodeling, suggesting a history of repetitive loading.

To our knowledge, the macroscopic appearance of a bone surface showing MTSS lesions has not been presented in the literature and cannot be obtained from living patients. Thus, this skeleton from medieval Rhodes presenting lesions with morphological and distributional specificity indicative of MTSS, in association with mechanical adaptation to loading and osteoarthritis lesions, introduces a novel diagnosis in paleopathology, which is also of interest in modern orthopedics.

ASP: examination of skeleton, interpretation of findings, and writing of manuscript. NV: interpretation of findings, and writing and critical evaluation of manuscript. DGT and GL: interpretation of findings and critical evaluation of manuscript. TP: design of the study, recovery and examination of skeleton, interpretation of findings, and critical evaluation of manuscript.

- Jurmain RD, Kilgore L. Skeletal evidence of osteoarthritis: a palaeopathological perspective. Ann Rheum Dis 1995; 54: 443-50.

- Moen MH, Tol JL, Weir A, Steunebrink M, De Winter TC. Medial tibial stress syndrome: a critical review. Sports Med 2009; 39: 523-46.

- Ortner DJ. Identification of pathological conditions in human skeletal remains. 2nd edition. Elsevier 2003.

- Thomas RH, Daniels TR. Ankle arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2003; 85: 923-36.

- Yates B, White S. The incidence and risk factors in the development of medial tibial stress syndrome among naval recruits. Am J Sports Med 2004; 32:7 72-80.