Abstract

Background and purpose — Slipped capital femoral epiphysis is thought to result in cam deformity and femoroacetabular impingement. We examined: (1) cam-type deformity, (2) labral degeneration, chondrolabral damage, and osteoarthritic development, and (3) the clinical and patient-reported outcome after fixation of slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE).

Methods — We identified 28 patients who were treated with fixation of SCFE from 1991 to 1998. 17 patients with 24 affected hips were willing to participate and were evaluated 10–17 years postoperatively. Median age at surgery was 12 (10–14) years. Clinical examination, WOMAC, SF-36 measuring physical and mental function, a structured interview, radiography, and MRI examination were conducted at follow-up.

Results — Median preoperative Southwick angle was 22o (IQR: 12–27). Follow-up radiographs showed cam deformity in 14 of the 24 affected hips and a Tönnis grade > 1 in 1 affected hip. MRI showed pathological alpha angles in 15 affected hips, labral degeneration in 13, and chondrolabral damage in 4. Median SF-36 physical score was 54 (IQR: 49–56) and median mental score was 56 (IQR: 54–58). These scores were comparable to those of a Danish population-based cohort of similar age and sex distribution.

Median WOMAC score was 100 (IQR: 84–100).

Interpretation — In 17 patients (24 affected hips), we found signs of cam deformity in 18 hips and early stages of joint degeneration in 10 hips. Our observations support the emerging consensus that SCFE is a precursor of cam deformity, FAI, and joint degeneration. Neither clinical examination nor SF-36 or WOMAC scores indicated physical compromise.

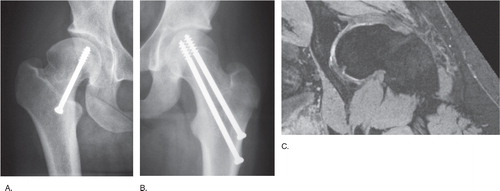

In femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), repeated trauma to the acetabular labrum and adjacent chondral structures may result in labral degeneration, tearing of the labrum, chondral delamination, and osteoarthritis development. Cam-type deformity is characterized by loss of sphericity of the femoral head and decreased head/neck offset laterally and anteriorly (). This deformity has been identified in 17–24% of men and in 4% of women (CitationGosvig et al. 2008, Reichenbach et al. Citation2010) and is believed to be one of the main contributors to osteoarthritic development. The etiology of cam-type deformity remains unclear (Beck et al. Citation2005, Ganz et al. Citation2008, Jessel et al. Citation2009, CitationLeunig et al. 2009, Barros et al. Citation2010, Klit et al. Citation2011), high intensity of sports activity during adolescence has been associated with increased risk of cam-type deformity (Siebenrock et al. Citation2011).

Figure 1. A. CAM-type deformity with characteristic loss of sphericity of the femoral head and decreased head/neck offset laterally and anteriorly after SCFE with in situ screw fixation. B. SCFE with loss of sphericity of the femoral head and decreased head/neck offset laterally and anteriorly and in situ screw fixation. C. Radial reconstruction of a MRI 3T scan showing anterior CAM-type deformity with the characteristic loss of sphericity of the femoral head and decreased head/neck offset anteriorly at 15 years after SCFE with in situ screw fixation.

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is thought to be a precursor of cam-type deformity and therefore possibly also development of osteoarthritis (Murray Citation1965, Stulberg et al. Citation1975, Harris Citation1986, Leunig et al. Citation2000, Citation2009, Beck et al. Citation2005, Ganz et al. Citation2008, Gosvig et al. Citation2008b, Murray and Wilson Citation2008, Mamisch et al. Citation2009, Barros et al. Citation2010, Klit et al. Citation2011). In typical SCFE (), the epiphysis stays in the acetabular socket and the femoral metaphysis is displaced anteriorly and superiorly, creating the impression of an epiphysis that has slipped posteriorly and inferiorly. The consequence is a reduced or complete loss of head/neck offset, which resembles a prototype of cam-type deformity (Harris Citation1986, Mintz et al. Citation2005, Lehmann et al. Citation2006, Jessel et al. Citation2009).

SCFE is the most common hip disorder in adolescence (Lehmann et al. Citation2006, Gholve et al. Citation2009) with a prevalence of asymptomatic so-called silent SCFE of 3% in girls and 10% in boys (Lehmann 2008, personal communication), which is less than the population-based prevalence estimates of cam-type deformity in adults of 4–24% (Lehmann 2008, Gosvig et al. Citation2010, Reichenbach et al. Citation2010) .

To test the hypothesis that SCFE results in cam-type deformity, we raised the following questions: (1) does cam-type deformity or (2) do labral degeneration, chondrolabral damage, and osteoarthritic development appear at 10–17 years of follow-up after fixation of SCFE; and (3) is the clinical and patient-reported outcome affected?

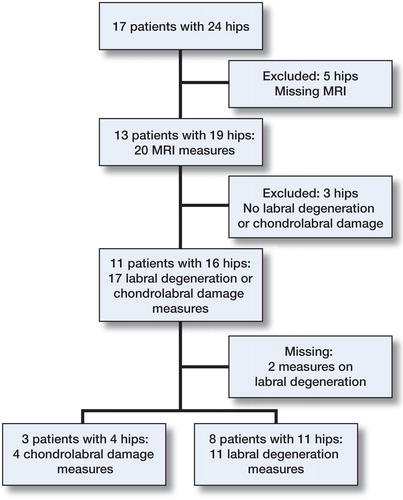

Patients and methods ()

Figure 2. Flow diagram for obtainment of measures of labral degeneration and chondrolabral damage in affected hips.

We searched databases at Aarhus University Hospital and Hvidovre University Hospital and identified 28 patients who had had in situ fixation of SCFE between 1991 and 1998 and had not been converted to a total hip arthroplasty. 17 patients (10 women) with 24 affected hips were willing to participate in this ethics committee-approved study (no. M-20080062).

Of the 17 participating patients, 10 had unilateral SCFE and 7 had bilateral SCFE. 3 patients with unilateral SCFE had prophylactic simultaneous contralateral pinning performed. Based on Southwick’s definitions (Southwick Citation1967), we identified 18 hips with a chronic slip, 2 with acute-on-chronic, 2 with acute slip (pain < 3 weeks), and 2 others whose level of chronicity could not be specified. Median age at surgery was 12 (10–14) years. 1 patient had subsequent proximal femoral valgus osteotomy performed. The patients were evaluated in 2008 with a mean follow-up of 15 (10–17) years. The 11 patients (3 women) who declined to participate in the follow-up had a median age at surgery of 12 (10–13) years.

Hips were operated on with insertion of 1 or 2 screws through a minimal skin incision. The aim was central placement of the screw in the femoral head in both radiographic planes. Patients had postoperative radiographs taken. In many cases they were followed for 1 year postoperatively and in some cases they were followed until radiographic closure of the physis. Radiographic examinations consisted of 2 views, most often AP and Lauenstein views.

All clinical examinations were performed by 2 of the authors: AT in Aarhus and KG in Hvidovre. Follow-up included clinical examination, WOMAC and SF-36 questionnaires, conventional radiography (AP pelvic and Lauenstein views), and MRI. Clinical examination included ROM and the impingement test. The impingement test was performed by internally rotating and adducting the 90o-flexed hip and they were considered positive if groin pain resulted (Troelsen et al. Citation2009). At follow-up, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was assessed using the SF-36 version 1 questionnaire. Data are presented as physical and mental component scores and are compared with normative data for a cohort of similar age from the Danish population (Bjørner et al. Citation1997). To assess hip-specific patient-reported outcome, we used the WOMAC questionnaire (Bellamy et al. Citation2011). Data were transformed to a scale from 0 to 100 (100 being the best possible score), taking into account differences in scale length.

MRI was performed at both hospitals. Hips with retained metal implants (n = 3) were excluded from MRI evaluation as a result of metal artifacts distorting the area close to the implant. All other hips were included and found to be suitable for evaluation, including the opposite hip to those with retained implants. At Aarhus University Hospital, MRI was performed using a Philips 3-T scanner (Best, the Netherlands). Proton density-weighted SPAIR sequences in the sagittal, coronal, and axial planes were obtained followed by a coronal T1 sequence and a T2-weighted 3-D sequence with fat suppression. At Hvidovre University Hospital, all MRIs were performed using a Siemens Trio 3-T scanner (Erlangen, Germany) (). Proton density-weighted fat-saturated turbo spin echo sequences in the coronal, axial, and sagittal planes were obtained, followed by a unique Dess 3-D sequence. Radial reconstructions were obtained from the 3-D sequences around the axis of the femoral neck. Cam malformations were assessed by the alpha angle, as described by Nötzli et al. (Citation2002). Labral degeneration was defined by irregular margins and intermediate signal intensity. Chondrolabral damage was identified by a linear band of high signal intensity, detected in the labrum or at the chondrolabral transition zone. Based on the primary localization of labral degeneration or chondrolabral damage, each condition was assigned to 1 of 4 acetabular quadrants: anteroinferior, anterosuperior, posterosuperior, or posteroinferior (Troelsen et al. Citation2007). Although 1.5-T MRI arthrography has been the gold standard in evaluating labral changes and chondral changes, non-contrast conventional MRI has been valid in detecting structural labral changes (Mintz et al. Citation2005, Robinson Citation2012). All MRIs were assessed by 2 of the authors (EM and KG) as consensus readings; the first is a senior consultant in radiology specialized in orthopedic MRI and the latter is a radiologist with 3 years of experience.

All preoperative radiographs were digitized and—together with follow-up radiographs—examined using Synedra software (Synedra View Personal Version 3; Synedra Information Technologies GmbH, Innsbruck, Austria). All radiographs were assessed by one author (JK). To describe the severity of the SCFE, the Southwick angle was measured on the preoperative radiographs in the frog-leg lateral view (Southwick Citation1967, Citation1984). A Southwick angle in the interval 30° to 50° was considered a moderate slip (Southwick Citation1967, Loder et al. Citation2006). In 8 of 24 hips, measurements of the Southwick angle could not be made because only preoperative AP views were available. The median preoperative Southwick angle was 22° (12–27). The triangular index described by Gosvig et al. (Citation2007) was used to assess whether cam deformity was present at follow-up. An index of > 2 describes definite cam-type deformity. Osteoarthritic changes were assessed according to the Tönnis classification (Tönnis Citation1976). We have previously reported intra- and interobserver variance measures of the Tönnis classification and the triangular index (Gosvig et al. Citation2007, Troelsen et al. Citation2010).

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were performed on all variables of interest. Categorical variables were displayed with crude number (rate), and, if not otherwise stated, data are presented as continuous variables with median and interquartile range (first and third quartile). We assumed dependency in the hips of the same patient. Since some patients had 2 affected hips, empirical 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for all variables to show their accuracy (Efron et al. Citation1996). These CIs are based on bootstraps with 10,000 samplings with replacement at the patient level. Extension, flexion, internal rotation, and external rotation were tested for differences between the affected hips and the unaffected hips. Again, because of the within-patient hip dependency, a bootstrap hypothesis test was preformed with 10,000 permutations at the patient level and we used the t-test to calculate the test statistic. If not otherwise stated, data are presented as median with interquartile range. Data were analyzed using R version 3.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

SF-36 data were processed using the software supplied for the SPSS package.

Results

On conventional radiographs at the last follow-up, the triangular index was pathological (> 2) in 14 of 22 affected hips (rate = 0.3, 95% CI: 0.4–0.9), indicative of cam-type deformity. In 15 of 17 affected hips (88%, CI: 65–100) evaluated by MRI at follow-up, the alpha angle of Nötzli et al. was > 55°, representing a pathological angle indicative of cam-type deformity. The median alpha angle was 83° (IQR: 62–95; CI: 62–95).

1 of 22 affected hips (0.05, CI: 0–0.1) had osteoarthritis, corresponding to a Tönnis grade of > 1 on conventional radiography.

MRI showed labral degeneration in 13 of 19 (rate = 0.7, CI: 0.4–0.9) affected hips and chondrolabral damage in 4 of 19 affected hips (0.2, CI: 0–0.4). Labral degeneration was located anterosuperior in 8 of 11 affected hips (0.7, CI: 0.4–0.1) and posterosuperior in 3 of 11 affected hips (0.3, CI: 0–0.6). Chondrolabral damage was located anterosuperior in 2 of 4 affected hips and posterosuperior in 2 of 4 affected hips.

The median SF-36 physical component score (PCS) was 54 (49–56, CI: 45–56) and the median mental component score (MCS) was 56 (54–58, CI: 55–58). The scores for a cohort with similar age from the Danish population were 56 for the PCS and 56 for the MCS (Bjørner et al. Citation1997). The median WOMAC score of the affected hips was 99 (87–100, CI: 87–100) and that of the unaffected hips was 100 (97–100, CI: 96–100). ROM was similar between affected and unaffected hips (). 6 of 24 affected hips (rate = 0.3, CI: 0.01–0.5) had a positive impingement test, as compared to 1 of 10 unaffected hips (0.1, CI: 0–0.3) ().

Table 1. ROM for affected and unaffected hips

Table 2. Association between the variables

Discussion

During the last two decades, it has become increasingly evident that even subtle hip deformities can cause FAI, and thereby osteoarthritis development. SCFE is known to be a precursor of cam deformity, and thereby OA. However, no studies have evaluated the clinical and radiological presentation, including MRI and patient-reported outcome, at long-term follow-up. We therefore asked the following questions: (1) does cam deformity or (2) do labral degeneration, chondrolabral damage, and osteoarthritic development appear at 10–17 years of follow-up after fixation of SCFE; and (3) is the clinical and patient-reported outcome affected?

Our study had several limitations. Firstly, it was a small study cohort of 17 patients and 24 affected hips, which limit general conclusions. However, our database searches ensured that all patients eligible for inclusion were invited, reducing the potential for selection bias. Secondly, clinical follow-up was performed by 2 authors, 1 at each center. This could, as a result of interobserver variability, have biased the results at follow-up. However, the radiographic evaluations were performed by single observers only, thus eliminating interobserver variability. Thirdly, although 10- to 17-year follow-up is considered long-term in classical hip surgery, this may not be so in the context of development of degenerative joint disease. Thus, our follow-up cannot be considered final, and further degenerative joint disease can be anticipated.

On both standard AP pelvic radiographs and MRI, we found that most hips had signs of cam-type structural hip deformity. On MRI, the measured pathological alpha angles revealed a wide range of reduced femoral head/neck offset and cam deformity. Furthermore, all alpha angles were above the suggested normal value of 42° (Nötzli et al. Citation2002, Beaule et al. Citation2005, Miese et al. Citation2010). In agreement with our findings, on plain AP radiographs Zilkens et al. (Citation2011), Fraitzl et al. (Citation2007), and Wensaas et al. (Citation2012) found a reduced head/neck offset in most patients after SCFE.

Only 1 previous study () has evaluated the consequences of SCFE by MRI (Miese et al. Citation2010). We found a wide range of increased alpha angles and mainly an anterosuperior localization of labral degeneration and chondrolabral damage. These findings are similar to the observations by Miese et al. in their MRI study of 26 patients (35 hips) 12 years after SCFE. Furthermore, the anterosuperior localization of degenerative changes is reported in several studies on hips with cam-type deformity (Leunig et al. Citation2000, Citation2009, Ganz et al. Citation2008, Reichenbach et al. Citation2011). In their cross-sectional MRI study of asymptomatic young men, Reichenbach et al. (Citation2010) found cam deformity, cartilage damage, and labral degeneration in the same location, the anterosuperior quadrant of the acetabulum. Similar to what we found, Miese et al. (Citation2010) found preosteoarthritic changes on T2-weighted MRI in 33 patients 12 years after SCFE. Like us, they did not find any relationship between preosteoarthritic changes and the clinical presentation. In agreement with our findings, Zilkens et al. (Citation2011) found no signs of osteoarthritis on plain AP radiographs at follow-up of 38 patients 11 years after SCFE. Wensaas et al. (Citation2012) found OA in 10 of 43 SCFE hips 37 years after SCFE. The high prevalence of anterosuperior pre-osteoarthritic changes and reduced head/neck offset found in this young patient group adds to the hypothesis that SCFE results in cam-type deformity and FAI (Beck et al. Citation2005, Ganz et al. Citation2008, Jessel et al. Citation2009, Leunig et al. 2009, Barros et al. Citation2010, Klit et al. Citation2011).

Table 3. SCFE follow-up studies evaluating CAM deformity, osteoarthritis, and patient-reported outcome

The patient-reported HRQoL and hip-specific outcome (SF-36 and WOMAC questionnaires) did not reveal any signs of hip symptoms or functional compromise. These findings are consistent with the literature, in which symptomatic joint degeneration resulting from cam-type deformity normally does not develop until the fifth decade of life (Stulberg et al. Citation1975, Boyer et al. Citation1981, Beck et al. Citation2005, Wei et al. Citation2011, Wensaas et al. Citation2011, Citation2012). However, Zilkens et al. (Citation2011) found decreased SF-36 scores but only for the subscale parameters of physical function and role physical. While 2 studies (Southwick Citation1967, Mamisch et al. Citation2009) have shown that patients with SCFE have reduced ROM, especially in internal rotation and flexion, our patients had normal ROM. However, reduced ROM correlates with the degree of slip (Southwick Citation1967, Tönnis Citation1976, Loder et al. Citation2006, Fraitzl et al. Citation2007, Mamisch et al. Citation2009), and our patients all had mild or moderate slip. We observed that a positive impingement test was more frequent in affected hips than in unaffected hips, thus indicating at least some joint affection.

In conclusion, our observations support the emerging consensus that SCFE is a precursor of cam deformity, FAI, and joint degeneration.

Study idea and design: KG, KS, and AT. Collection of data: JK, KG, EM, JG, and AT. Analysis and/or interpretation of data: all authors. Writing of draft manuscript: JK, AT, and TK. Editing and approval of manuscript: all authors.

We thank physicist Peter Magnusson for development of the unique Dess 3-D sequence used in this study. We also thank the surgeons at Aarhus University Hospital and Hvidovre University Hospital for their work with this patient group over the years.

No competing interests declared.

- Barros H JM, Camanho GL, Bernabé AC, Rodrigues MB, Leme L EG. Femoral head-neck junction deformity is related to osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop 2010; (48) (7): 1920–5.

- Beaule P, Zaragoza E, Motamedi K, Copelan N, Dorey F. Three-dimensional computed tomography of the hip in the assessment of femoroacetabular impingement. J Orthop Res 2005; 23 (6): 1286–92.

- Beck M, Kalhor M, Leunig M, Ganz R. Hip morphology influences the pattern of damage to the acetabular cartilage: femoroacetabular impingement as a cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2005; 87 (7): 1012–8.

- Bellamy N, Wilson C, Hendrikz J. Population-based normative values for the Western Ontario and McMaster (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index: part I. Semin Arthritis Rheum. Elsevier Inc. 2011; 41 (2): 139–48.

- Bjørner JB, Damsgaard MT, Watt T, Bech P, Rasmussen NK, Kristensen TS, et al Dansk maual til SF-36. 1997.

- Boyer DW, Mickelson MR, Ponseti IV. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Surgery 1981; 63 (I): 85–95.

- Efron B, Halloran E, Holmes S. Bootstrap confidence levels for phylogenetic trees. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996; 93 (23): 13429–34.

- Fraitzl CR, Käfer W, Nelitz M, Reichel H. Radiological evidence of femoroacetabular impingement in mild slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a mean follow-up of 14.4 years after pinning in situ. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2007; 89 (12): 1592–6.

- Ganz R, Leunig M, Leunig-Ganz K, Harris WH. The etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip: an integrated mechanical concept. Clin Orthop 2008; (466)(2): 264–72.

- Gholve PA, Cameron DB, Millis MB. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis update. Curr Opin Pediatr 2009; 21 (1): 39–45.

- Gosvig KK, Jacobsen S, Palm H, Sonne-Holm S, Magnusson E. A new radiological index for assessing asphericity of the femoral head in cam impingement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2007; 89 (10): 1309–16.

- Gosvig K, Jacobsen S, Sonne-Holm S, Gebuhr P. The prevalence of Cam-type deformity of the hip joint: A survey of 4151 subjects of the Copenhagen Osteoarthritis Study. Acta Radiol 2008a; 4: 436–41.

- Gosvig KK, Jacobsen S, Sonne-Holm S, Gebuhr P. The prevalence of cam-type deformity of the hip joint: a survey of 4151 subjects of the Copenhagen Osteoarthritis Study. Acta Radiol 2008b; 49 (4): 436–41.

- Gosvig KK, Jacobsen S, Sonne-Holm S, Palm H, Troelsen A. Prevalence of malformations of the hip joint and their relationship to sex, groin pain, and risk of osteoarthritis: a population-based survey. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2010; 92 (5): 1162–9.

- Harris WH. Etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop 1986; (213): 20–33.

- Jessel B RH, Zurakowski D, Zilkens C, Burstein D, Gray ML, Kim Y. Radiographic and patient factors associated with pre-radiographis osteoarthritis in hip dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2009; 91: 1120–9.

- Klit J, Gosvig K, Jacobsen S, Sonne-Holm S, Troelsen A. The prevalence of predisposing deformity in osteoarthritic hip joints. Hip Int (Internet) 2011; 21 (5): 537–41.

- Lehmann CL, Arons RR, Loder RT, Vitale MG. The epidemiology of slipped capital femoral epiphysis: an update. J Pediatr Orthop 2006; 26 (3): 286–90.

- Leunig M, Casillas MM, Hamlet M, Hersche O, Nötzli H, Slongo T, et al. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: early mechanical damage to the acetabular cartilage by a prominent femoral metaphysis. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71 (4): 370–5.

- Leunig M, Beaulé PE, Ganz R. The concept of femoroacetabular impingement: current status and future perspectives. Clin Orthop 2009; (467) (3): 616–22.

- Loder RT, O’Donnell PW, Didelot WP, Kayes KJ. Valgus slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop Part B 2006; 26: 594–600.

- Mamisch TC, Kim Y-J, Richolt JA, Millis MB, Kordelle J. Femoral morphology due to impingement influences the range of motion in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop 2009; (467) (3): 692–8.

- Miese FR, Zilkens C, Holstein A, Bittersohl B, Kröpil P, Jäger M, et al. MRI morphometry, cartilage damage and impaired function in the follow-up after slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Skeletal Radiol 2010; 39 (6): 533–41.

- Mintz DN, Hooper T, Connell D, Buly R, Padgett DE, Potter HG. Magnetic resonance imaging of the hip: detection of labral and chondral abnormalities using noncontrast imaging. Arthroscopy 2005; 21 (4): 385–93.

- Murray AW, Wilson N IL. Changing incidence of slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a relationship with obesity? J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008; 90 (1): 92–4.

- Murray RO. The aetiology of primary osteoarthritis of the hip. Br J Radiol 1965; 38: 810–24.

- Nötzli HP, Wyss TF, Stoecklin CH, Schmid MR, Treiber K, Hodler J. The contour of the femoral head-neck junction as a predictor for the risk of anterior impingement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2002; 84 (4): 556–60.

- Reichenbach S, Jüni P, Werlen S, Nüesch E, Pfirrmann CW, Trelle S, et al. Prevalence of cam-type deformity on hip magnetic resonance imaging in young males: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010; 62 (9): 1319–27.

- Reichenbach S, Leunig M, Werlen S, Nüesch E, Pfirrmann CW, Bonel H, et al Association between cam-type deformities and MRI-detected structural damage of the hip: A cross-sectional study in young males. Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63 (12): 4023–30.

- Robinson P. Conventional 3-T MRI and 1.5-T MR arthrography of femoroacetabular impingement. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012; 199 (3): 509–15.

- Siebenrock KA, Ferner F, Noble PC, Santore RF, Werlen S, Mamisch TC. The Cam-type deformity of the proximal femur arises in childhood in response to vigorous sporting activity. Clin Orthop 2011; (469): 3229–40.

- Southwick WO. Osteotomy through the lesser trochanter for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1967; 49: 807–35.

- Southwick WO. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1984; 66: 1151–2.

- Stulberg D, Cordell L, Harris WH, Ramsey P, MacEwen D. Unrecognized childhood hip disease: a major cause of idiopathic osteoarthritis of the hip. Hip Proc Third Open Sci Meet Hip Soc 1975: 212–28.

- Troelsen A, Jacobsen S, Bolvig L, Gelineck J, Rømer L, Søballe K. Ultrasound versus magnetic resonance arthrography in acetabular labral tear diagnostics: a prospective comparison in 20 dysplastic hips. Acta Radiol 2007; 48 (9): 1004–10.

- Troelsen A, Mechlenburg I, Gelineck J, Bolvig L, Jacobsen S, Søballe K. What is the role of clinical tests and ultrasound in acetabular labral tear diagnostics? Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (3): 314–8.

- Troelsen A, Rømer L, Kring S, Elmengaard B, Søballe K. Assessment of hip dysplasia and osteoarthritis : Variability of different methods. Acta Radiol 2010; 51 (2): 187–93.

- Tönnis D. Normal values of the hip joint for the evaluation of X-rays in children and adults. Clin Orthop 1976; (119): 39–47.

- Wei S, Zhen-cai S, Yu-run Y, Bai-liang W, Wan-shou G, Zhao-hui L. Early and middle term results after surgical treatment for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Orthop Surg 2011; 3 (1): 22–7.

- Wensaas A, Svenningsen S, Terjesen T. Long-term outcome of slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a 38-year follow-up of 66 patients. J Child Orthop 2011; 5 (2): 75–82.

- Wensaas A, Gunderson RB, Svenningsen S, Terjesen T. Femoroacetabular impingement after slipped upper femoral epiphysis: the radiological diagnosis and clinical outcome at long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg (Br)(internet) 2012; 94 (11): 1487–93.

- Zilkens C, Bittersohl B, Jäger M, Miese F, Schultz J, Kircher J, et al. Significance of clinical and radiographic findings in young adults after slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Int Orthop 2011; 35 (9): 1295–301.