Abstract

Background and purpose — For the treatment of leg-length discrepancies (LLDs) of between 2 and 5 cm in adolescent patients, several epiphyseodesis options exist and various complications have been reported. We reviewed the 8- to 15-year outcome after temporary epiphyseodesis in patients with LLD.

Patients and methods — 34 children with LLD of up to 5 cm were included in the study. Mean age at epiphyseodesis was 12.8 (10–16) years. Temporary epiphyseodesis was performed with Blount staples or 8-plates. The LLD was reviewed preoperatively, at the time of implant removal, and at follow-up. Every child had reached skeletal maturity at follow-up. Long-standing anteroposterior radiographs were analyzed with respect to the mechanical axis and remaining LLD at the time of follow-up. Possible complications were noted.

Results — The mean LLD changed from 2.3 (0.9–4.5) cm to 0.8 (–1.0 to 2.6) cm at follow-up (p < 0.001). 21 patients had a final LLD of < 1 cm, and 10 had LLD of < 0.5 cm. At the time of follow-up, in 32 patients the mechanical axis crossed within Steven’s zone 1. No deep infections or neurovascular lesions were seen. 4 implant failures occurred, which were managed by revision.

Interpretation — Temporary epiphyseodesis is an effective and safe option for the treatment of LLD. The timing of the procedure has to be chosen according to the remaining growth, facilitating a full correction of the LLD. If inaccurate placement of staples is avoided, substantial differences between the mechanical axes of both legs at skeletal maturity are rare.

Permanent epiphyseodesis was introduced by Phemister in 1933 (Phemister Citation1933) and temporary epiphyseodesis was introduced by Blount in 1949 (Blount and Clark Citation1949). The effectiveness of both methods for correction of angular deformities has been confirmed by several authors (Howorth Citation1971, Pistevos and Duckworth Citation1977, Stevens et al. Citation1999). However, a variety of complications have been reported, ranging from buried, misplaced, or fractured staples, and premature physeal closure or deviation of the mechanical axis (Frantz Citation1971).

There have only been a few reports on correction of LLD by temporary epiphyseodesis (Sengupta et al. Citation1993, Raab et al. Citation2001, Gorman et al. Citation2009). No reports have concentrated on the incidence and extent of secondary angular deformities at the time of skeletal maturity after temporary epiphyseodesis in patients with LLD. Thus, the primary goals of this study were to evaluate (1) the final difference in limb length, and (2) the final mechanical axis at the time of skeletal maturity in patients who had undergone a temporary epiphyseodesis for the treatment of LLD.

Patients and methods

Patients

Inclusion criteria were (1) a temporary epiphyseodesis performed for LLD of up to 5 cm (predicted LLD at time of skeletal maturity), (2) consistent preoperative, postoperative, and follow-up radiographs, and (3) skeletal maturity at the time of final follow-up examination. In the 6 children with an estimated LLD of less than 2 cm, the treatment decision was carefully discussed with the child and his/her parents.

61 patients with LLD were treated by temporary epiphyseodesis. 34 (21 of them boys) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and underwent follow-up examination. Temporary epiphyseodesis was performed with Blount staples in 30 children and with 8-plates in 4 children. Mean age at the time of epiphyseodesis was 12.8 (10–16) years. 16 children had idiopathic LLD, followed by a secondary LLD in 8 cases ().

Table 1. Patient data

Epiphyseodesis and hardware removal

To predict the LLD at skeletal maturity and to define the optimal time for surgery, we used the Anderson and Green growth-remaining charts and the Paley multiplier method (Anderson et al. Citation1963, Paley et al. Citation2000). The epiphyseodesis was performed at the distal femoral physis, the proximal tibial physis, or both, depending on the location of the main inequality. We inserted 2 Blount staples or one 8-plate on the medial and lateral side of the physis. The fibular physis was not treated. The main goal was a balanced limb length at the time of skeletal maturity, with both knees at the same level. No overcorrection according to the estimated LLD at maturity was intended. The implants should completely bridge the physis. The prongs/screws should be placed parallel to the physis and at an equal distance from the anterior and posterior margins of the bone. To ensure proper positioning of hardware, we performed intraoperative fluoroscopy and postoperative radiography in 2 planes. Implants were removed at maturity or when the limb length was balanced.

Radiographic analysis

Digital radiography at the time of treatment was not available at our institution. 3 radiographs centred over the hip, knee, and ankle joint with an underlying measuring tape were obtained. This technique was common for LLD analysis at our institution until 2008. At the time of follow-up, digital radiography with long, standing anteroposterior radiographs of the lower extremity was available. To ensure that the radiographs are standardized, the patient stands with the back exactly parallel to the back-pillar of the radiographic equipment, patellae forward, with weight balanced on both feet and straight legs.

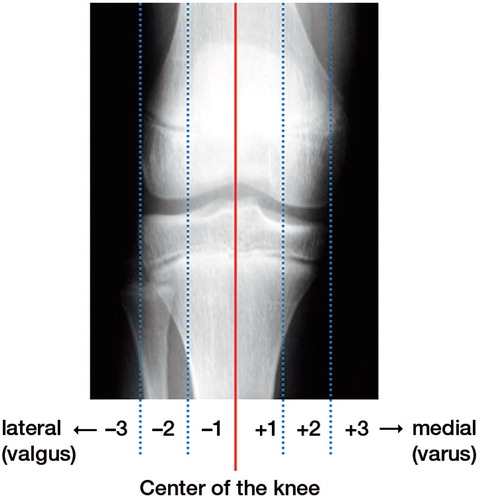

All radiographs were evaluated for limb length in a standardized manner. The long, standing radiographs at the time of follow-up were analyzed for the mechanical axis according to Stevens et al. (Citation2004) (), for the mechanical axis deviation (MAD) referred to the center of the knee joint, the lateral distal femoral angle (LDFA), and the medial proximal tibial angle (MPTA). The uninstrumented leg acted as the reference. Staple placement was graded as adequate or inadequate depending on the location in relationship to the physis: incorrectly placed staples were not parallel to the physis, did not capture the physis, or had dislodged from the original position during the postoperative period.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics are given as mean (range). Student’s paired t-test was used to compare pre- and post-treatment values. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Ethics

The study was approved by the institutional review board (ethics committee, reference number: PV4505). Written informed consent was obtained from the parents and from the participants.

Results

Epiphyseodesis and hardware removal

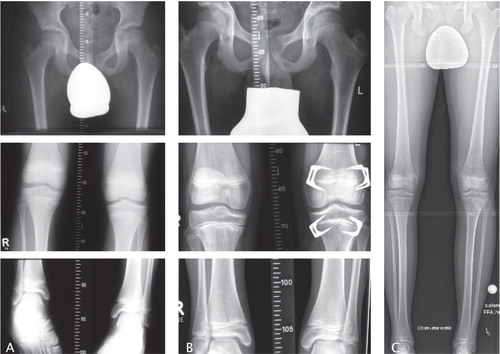

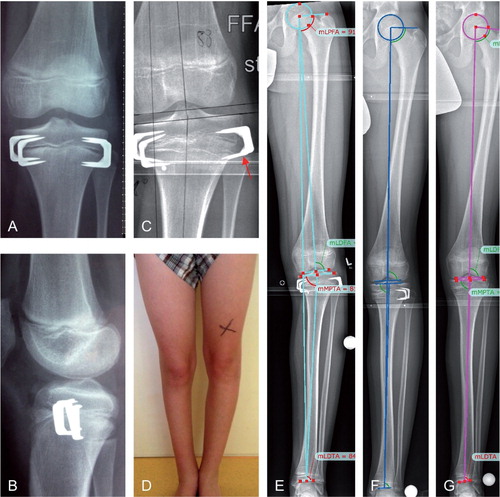

We used Blount staples in 30 children and 8-plates in 4 children. The implants were inserted only on the femoral side in 14 children, and on the tibial side in 8 children. In 12 children, combined femoral and tibial epiphyseodesis was performed ( and ). The position of the implant was rated as being adequate in 32 children. In 2 children, a staple was placed too far anteriorly and was therefore rated as having inadequate placement. In these cases, no complications occurred that necessitated revision surgery. All staples or plates captured the physis at the time of insertion. The 2 children with the misplaced staples had no secondary deformity during the treatment period.

Figure 2. 13-year-old boy with an idiopathic leg-length discrepancy (LLD). A. radiographs centered on the hips, knees, and ankles with LLD of 4.5 cm (right). B. LLD corrrection to 0.1 cm 40 months after femoral and tibial epiphyseodesis. C. Long-standing anteroposterior radiographs at time of follow-up.

In 33 cases, the implants were removed after mean 31 (7–69) months. Mean age at removal was 15.2 (11–19) years (14.5 (11–17) years for girls and 15.5 (13–19) years for boys). In 7 cases, the LLD was balanced before physeal closure. 1 patient did not want to have the staples removed after physeal closure.

Follow-up

All 34 patients were available for the follow-up investigation. Mean follow-up time was 7.7 (4.2–15) years. Mean age at this time was 20 (15–28) years.

Leg-length discrepancy (LLD)

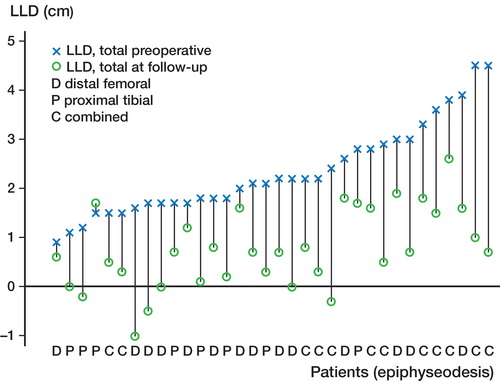

The mean LLD preoperatively was 2.3 (0.9–4.5) cm and the predicted LLD at maturity was 2.6 (1.0-5.0) cm. At the time of implant removal, the LLD was reduced to 0.9 (–1.0 to 2.4) cm (p < 0.001). Subsequently, no alteration occurred until follow-up. Compared with the initial LLD, the temporary epiphyseodesis resulted in a mean LLD correction of 1.6 (–0.2 to 3.8) cm (p < 0.001). 1 child had a final LLD of > 2 cm, 21 children had a final LLD of < 1 cm, and 10 had a final LLD of < 0.5 cm. The mean difference in knee joint level of the operated limb and the uninstrumented limb at the time of follow-up was 0.3 (–3.4 to 2.7) cm (p = 0.2) ( and ).

Table 2. Leg-length-discepancy and mechanical axis

Mechanical axis

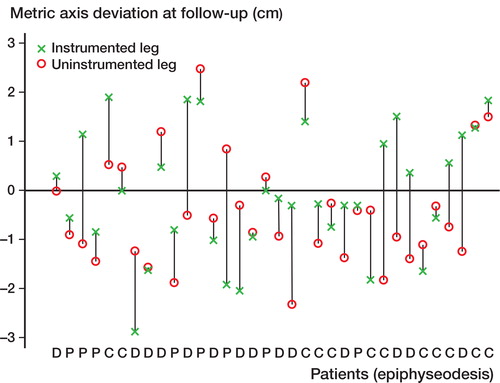

Before epiphyseodesis, none of the children had an angular deformity on clinical examination. At the time of follow-up, the mechanical axis of the operated limb was within Steven’s zone 1 in 32 children (15 medial and 17 lateral), and in zone 2 in 2 children (1 medial and 1 lateral). The mechanical axis of the uninstrumented leg crossed within zone 1 in 33 patients (9 medial and 24 lateral), and in only 1 case within zone 2. No axis deviation into zone 3 occurred.

The mean MAD of the operated leg at follow-up was –0.06 (–2.87 to 1.91) cm, and that of the uninstrumented leg was –0.4 (–2.31 to 2.48) cm (minus designates valgus). We considered a MAD of ≥ 1 cm to be clinically important. Consecutively, [authors: what do you mean by consecutively? /language editor] the axes of both legs differed by 0.34 (–2.77 to 2.78) cm (p = 0.1). The mean LDFA of the instrumented leg at the time of follow-up was 87.2° (81–94), and that of the uninstrumented leg was 86.5° (82–90). The mean MPTA of the operated limb measured 88.3° (83–94) at the time of follow-up, and that of the contralateral leg was 88.1° (82–92). We calculated a mean difference in angle between the instrumented leg and the uninstrumented leg of 0.7° (–8 to 9) according to the LDFA (p = 0.3) and of 0.2° (–7 to 8) according to the MPTA (p = 0.731) ( and ).

Complications

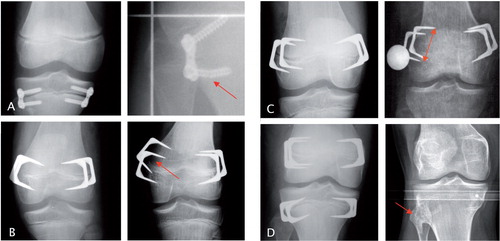

In 26 cases, the entire treatment was unenventful. No deep infections or neurovascular lesions were seen. None of the 34 children had a permanent decrease in knee motion or persistent knee pain. No genu recurvatum occurred. Complications occurred in 8 children (). 4 children had implant failure or loosening (), which was managed by repeated epiphyseodesis in 3 cases. Due to insufficient correction, an additional femoral epiphyseodesis was performed in 1 child and a shortening osteotomy was performed in another child. In 1 case, a medial tibial exostosis occurred after staple removal (). In 3 cases, a secondary angular deformity necessitated implant removal from the concave side. In these cases, a return to a normal mechanical axis was achieved ().

Figure 5. Complications. A. Implant failure. B. Loosening of staples. C. Bending of staples. D. Exostosis after removal of staples.

Figure 6. Secondary angular deformity. A and B. Accurate tibial stapling for LLD correction. C. Loosening of the lateral staples with subsequent varus deformity. D. Clinical picture with varus deformity of the left leg. E. Long, standing anteroposterior radiographs confirming the pathological (varus) mechanical axis. F. Correction of the mechanical axis 6 months after removal of staples from the concave side and replacement of staples at the convex side. G. Mechanical axis at the time of follow-up (FU).

Discussion

Besides nonoperative management for LLD of less than 2 cm, numerous surgical procedures exist: circumferential periosteal release (Wilde and Baker Citation1987), arteriovenous fistula (Hierton Citation1961), lumbar sympathectomy (Barr et al. Citation1950), inclusion of foreign bodies at the metaphyseal level (Castle Citation1971), and pulsed electromagnetic fields on the shorter leg. However, the results of these methods are inconsistent (Raab et al. Citation2001). Osteotomies and callus distraction are preferred in cases with LLD of more than 5 cm. The inhibition of growth by temporary or permanent epiphyseodesis appears to be a more accepted surgical treatment for LLD ranging from 2 to 5 cm.

Ilharreborde et al. (Citation2012) used transphyseal screws (PETS) for the treatment of LLD. The final loss of growth at maturity noted with PETS was only two-thirds of that predicted preoperatively; furthermore, use in the proximal tibia was associated with a substantial rate of complications, including valgus deformity (20%). These results argue for an eventual benefit of temporary epiphyseodesis using staples (Ilharreborde et al. Citation2012, Kemnitz et al. Citation2003), but Cabalzar (Citation1978) concluded that epiphyseal stapling should not be used for correction of LLD, as safer techniques for lengthening of the affected leg are available with low complication rates and the advantage of correction of associated deformities (Cabalzar Citation1978). Gorman et al. (Citation2009) noted inconsistent results in one quarter of their patients who still had a discrepancy in excess of 2 cm after epiphyseal stapling. In recent years, the 8-plate has been used to treat angular deformities and LLD. Lauge-Pedersen and Hägglund (Citation2013) reported that the 8-plate did not reduce growth when applied both medially and laterally in a symmetrical way at the proximal tibial physis for LLD treatment in 2 patients. In the present study, the 4 patients who were treated with 8-plates showed LLD correction similar to that in the patients treated with Blount staples. However, an implant breakage occurred in one case. If the remaining growth potential and the expected LLD correction can be estimated exactly, a percutaneous permanent epiphyseodesis would be the method of choice for LLD treatment, because implant-related complications are avoided and implant removal is not required. Kemnitz et al. (Citation2003) reviewed 57 patients who underwent percutaneous permanent epiphyseodesis for LLD correction. They reported good results in 39 patients with a final LLD of less than 1.5 cm, and identified the error in timing as the main problem associated with this technique.

At the time of follow-up, 33 out of 34 of our patients had a residual LLD of less than 2 cm, and 21 of 34 had less than 1 cm. Similar results have been reported by Watillon et al. (Citation1986), Sengupta et al. (Citation1993), and Raab et al. (Citation2001). Sengupta and colleagues noted a residual LLD of < 1 cm in two-thirds to three-quarters of their patients. A mild overcorrection at the time of skeletal maturity (0.2–1.0 cm) occurred in 4 of our patients. One girl had a final LLD of 2.6 cm, caused by a delayed initial presentation (14 years of age) and LLD of 3.8 cm.

Apart from over- and under-correction of LLD, a possible complication of epiphyseodesis is secondary angular deformity. In a series of 54 patients with LLD and a minimum follow-up of 2 years, Gorman et al. (Citation2009) reported a shift in the mechanical axis of > 1 cm toward varus in 27 patients after Blount stapling. To correct the varus deformity, a high tibial osteotomy became necessary in 6 cases. In contrast to that report, Sengupta and Gupta (Citation1993) noted an angular deformity in only 8 (2%) of 503 cases after stapling for LLD correction, requiring a staple removal from the concave side in 3 patients and an osteotomy in 2. Raab et al. (Citation2001) reported a mild deviation (4–9°) in the mechanical axis in 4 of 24 patients after stapling, but none of these patients needed an osteotomy. In the present study, no difference between the mechanical axes of both legs occurred at skeletal maturity. In 32 of 34 patients, the axes crossed within Steven’s zone 1, representing a physiological situation. An osteotomy did not become necessary to treat secondary angular deformities in any of our patients. In 3 patients, a staple removal from the concave side was successfully performed during the treatment period. We had no cases with superficial or deep wound infections and no neurovascular complications. Raab et al. (Citation2001) found no cases of deep infection after Blount’s stapling for correction of length discrepancies and angular deformities of the leg in 48 patients. Gorman et al. (Citation2009) reported 2 cases of a superficial suture abscess in a series of 54 patients after staple epiphyseodesis for limb-length inequality.

The limitations of our study include the retrospective design and the absence of preoperative standing anteroposterior radiographs of the lower extremity, precluding an accurate comparison of the mechanical axis before and after treatment. In addition, we cannot comment on sagittal plane deformities because we did not have standardized lateral radiographs at follow-up. Apart from the evaluation of the mechanical axis in the frontal plane, the analysis of the sagittal plane is of major interest. The sagittal plane uncovers recurvatum or procurvatum deformities, for example, which influence the functional range of motion. The major strength of the present study was the complete long-term follow-up in a large group of mature patients.

MS: data collection and interpretation, writing; KR: data analysis; SB: statistical analysis and interpretation; RS: study design, correction; MR: study design, interpretation, writing, correction.

No competing interests declared.

- Anderson M, Green WT, Messner MB. The classic growth and predictions of growth in the lower extremities. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1963; 45: 1-14.

- Barr JS, Stinchfield AJ, Reidy JA . Sympathica ganglionectomy and limb length in poliomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1950; 32: 793-802.

- Blount WP, Clarke GR. Control of bone growth by epiphyseal stapling. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1949; 31: 464–78.

- Cabalzar A. Erfahrungen mit der temporären Epiphyseodese nach Blount. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb 1978; 116: 335–62.

- Castle M. Epiphyseal stimulation. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1971; 53: 326–34.

- Frantz C. Epiphyseal stapling: a comprehensive review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1971; 77: 149–57.

- Gorman TM, Vanderwerff R, Pond M, MacWilliams B, Santora SD. Mechanical axis following staple epiphysiodesis for limb-length inequality. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2009; 91(10): 2430–9.

- Hierton T. Arteriovenous fistula for discrepancy in length of lower extremities. Acta Orthop Scand 1961; 31: 26–44.

- Howorth B. Knock knees. With special reference to the stapling operation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1971; (77): 233–46.

- Ilharreborde B, Gaumetou E, Souchet P et al. Efficacy and late complications of percutaneous epiphysiodesis with transphyseal screws. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2012; 94-B (2): 270-5.

- Kemnitz S, Moens P, Fabry G. Percutaneous epiphysiodesis for leg length inequality. J Pediatr Orthop B 2003; 12 (1): 69-71.

- Lauge-Pedersen H, Hägglund G. Eight plate should not be used for treating leg length discrepancy. J Child Orthop 2013; 7(4): 285-8.

- Paley D, Bhave A, Herzenberg JE, Bowen JR. Multiplier method for predicting limb-length discrepancy. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2000; 82(10): 1432–46.

- Phemister DB. Operative arrest of longitudinal growth of bones in the treatment of deformities. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1933; 15: 1–15.

- Pistevos G, Duckworth T. The correction of genu valgum by epiphyseal stapling. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1977; 59: 72–6.

- Raab P, Wild A, Seller K, Krauspe R. Correction of length discrepancies and angular deformities of the leg by Blount’s epiphyseal stapling. Eur J Pediatr 2001; 160: 668–74.

- Sengupta A, Gupta P. Epiphyseal stapling for leg equalization in developing countries. Int Orthop 1993; 17(1): 37–42.

- Stevens PM, Maguire M, Dales MD, Robins AJ. Physeal stapling for idiopathic genu valgum. J Pediatr Orthop 1999; 19(5): 645–9.

- Stevens PM, MacWilliams B, Mohr RA. Gait analysis of stapling for genu valgum. J Pediatr Orthop 2004; 24(1): 70–4.

- Watillon M, Hoet F. Epiphyseal stapling in the treatment of leg length inequality. Acta Orthop Belg 1986; 52: 209–16.

- Wilde GP, Baker G CW. Circumferential periosteal release in the treatment of children with leg length inequality. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1987; 69: 817–21.