Abstract

Background and purpose — Epidemiological studies of full-thickness rotator cuff tears (FTRCTs) have mainly investigated degenerative lesions. We estimated the population-based incidence of acute FTRCT using a new diagnostic model.

Patients and methods — During the period November 2010 through October 2012, we prospectively studied all patients aged 18–75 years with acute onset of pain after shoulder trauma, with limited active abduction, and with normal conventional radiographs. 259 consecutive patients met these inclusion criteria. The patients had a median age of 51 (18–75) years. 65% were males. The patients were divided into 3 groups according to the clinical findings: group I, suspected FTRCT; group II, other specific diagnoses; and group III, sprain. Semi-acute MRI was performed in all patients in group I and in patients in group III who did not recover functionally.

Results — We identified 60 patients with FTRCTs. The estimated annual incidence of MRI-verified acute FTRCT was 16 (95% CI: 11–23) per 105 inhabitants for the population aged 18–75 years and 25 (CI: 18–36) per 105 inhabitants for the population aged 40–75 years. The prevalence of acute FTRCT in the study group was 60/259 (23%, CI: 18–28). The tears were usually large and affected more than 1 tendon in 36 of these 60 patients. The subscapularis was involved in 38 of the 60 patients.

Interpretation — Acute FTRCTs are common shoulder injuries, especially in men. They are usually large and often involve the subscapularis tendon.

The epidemiology of degenerative rotator cuff tears has been studied for decades (CitationCodman and Akerson 1931, Codman 1990, CitationYamamoto et al. 2010, CitationLungo et al. 2012), but little attention has been given to acute ruptures. To our knowledge, there has only been 1 prospective epidemiological study on acute soft-tissue injury of the shoulder (Sorensen et al. 2007). That study found a prevalence of 32% of full-thickness rotator cuff tears (FTRCTs) in patients who were unable to abduct their arm above 90 degrees following an acute trauma of the shoulder.

Most rotator cuff tears are considered to be degenerative in nature (Codman 1990, CitationFukuda 2000, CitationPerry et al. 2009, CitationBenson et al. 2010, CitationDuquin et al. 2010, CitationOh et al. 2010). Differentiation between an acute traumatic tear in a previously healthy tendon, acute symptoms of a chronic tear, and traumatic extension of a chronic tear is difficult, even after advanced imaging techniques or surgery. Physical examination of the shoulder joint in the acute setting is difficult, and lacks accuracy (CitationBak et al. 2010). Specific diagnostic tests have been developed for rotator cuff tears. However, none of these tests have been developed for acute tears.

We started the Acute Shoulder Assessment Project (ASAP) in 2008. This is a screening system with physiotherapists (PTs) being the first-line practitioners who diagnose traumatic soft-tissue injuries of the shoulder in patients with limited abduction and with normal conventional radiographs. Physiotherapists are competent healthcare providers (CitationRazmjou et al. 2013) who are more available than shoulder surgeons. To our knowledge, the incidence of acute FTRCT has never been studied before. We estimated the population-based incidence of acute FTRCT using this new diagnostic screening model.

Patients and methods

Helsingborg Hospital is located in southern Sweden, with a catchment area/urban dominance area covering 268,000 inhabitants. All general practitioners and PTs in this area received written information about the study. From November 2010 through October 2012, 331 consecutive patients with trauma to the shoulder, with acute onset of shoulder pain and with limitations in active abduction, were enrolled from the Emergency Department or local primary care units in our catchment area after an initial physical examination and normal conventional radiographs. Only patients aged 18–75 years were included. Hill-Sachs impression fractures or bony Bankart lesions were not regarded as reasons for exclusion. Patients with severe comorbidity, previous shoulder surgery, glenohumeral osteoarthritis, or rheumatoid arthritis were excluded. The patients underwent physical examination by a PT within 10 days of the initial clinical assessment.

We defined acute rotator cuff tears as tears that occurred after direct or indirect trauma to the shoulder with sudden onset of symptoms in patients without ongoing shoulder disability. The study variables included age, sex, hand dominance, activity and mechanism of injury, previous shoulder discomfort, presence of ecchymosis, deformity or hypotrophy, and passive and active range of motion measured by use of a standard goniometer with the patient sitting. Several physical diagnostic rotator cuff tests were performed.

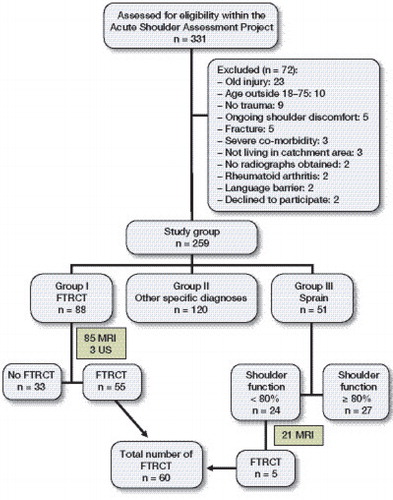

The patients were divided into 3 groups according to their clinical presentation (). Group I comprised 88 patients with positive rotator cuff tests and suspected FTRCT (FTRCT group). MRI was performed within 2 weeks in this group. Group II included 120 patients with other specific shoulder pathologies to explain their pain and disability, including AC joint sprain, calcifying tendinitis, adhesive capsulitis, brachial plexus traction, and shoulder instability. Group III included 51 patients with subtle reduction of active range of motion due to suspected partial tearing of the rotator cuff or a bursal bleeding. These patients were followed up with telephone interview by KEA 3 months after trauma. A clinical examination by a shoulder surgeon was undertaken if the patient rated his or her shoulder function to be less than 80% of their pre-injury level. MRI was performed if rotator cuff tear could not be ruled out at the physical examination. Patients who rated their function to be ≥ 80% were assumed not to have an FTRCT but were encouraged to return to be re-evaluated if there was not full recovery.

Population at risk

The population at risk in this healthcare region was determined through the National Population Registry, Statistics Sweden (www.scb.se/en_/). Studies investigating acute traumatic FTRCTs have shown that these tears are rare in patients less than 40 years of age (CitationBassett and Cofield 1983, CitationIde et al. 2007, CitationNamdari et al. 2008, CitationBjornsson et al. 2011, CitationPetersen and Murphy 2011). Thus, we defined the population at risk as inhabitants aged between 40 and 75 years who lived in the catchment area of Helsingborg Hospital in 2011. In 2011, the population at risk was 118,302 inhabitants.

Magnetic resonance imaging

All MRI examinations were performed on a 1.5 T scanner (Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany). A dedicated shoulder array coil was used. The arm was placed at the side of the body with the thumb pointing upwards. The following 7 sequences, all with a slice thickness of 3–4 mm, a 16-cm field of view (FOV), and 1 as the number of excitations (NEX) were obtained: (1) oblique sagittal T2-weighted turbo spin echo (TSE) (TR/TE = 4,390/80 ms, matrix 179 × 256); (2) oblique coronal T1-wighted (TR/TE = 465/14 ms, matrix 410 × 512); (3) oblique coronal short tau inversion recovery (STIR) (TR/TE = 4,720/27 ms, matrix 410 × 512); (4) oblique coronal proton density-weighted TSE with fat saturation (TR/TE = 3,100/13 ms, matrix 512 × 512); (5) oblique coronal proton density-weighted TSE with fat saturation (TR/TE = 2,890/94 ms, matrix 512 × 512); (6) axial proton density-weighted TSE with fat saturation (TR/TE = 3,530/13 ms, matrix 512 × 512); and (7) axial proton density-weighted TSE with fat saturation (TR/TE = 3,530/94 ms, matrix 512 × 512).

All MRI scans were read by a senior radiologist with more than 10 years’ experience of MRI shoulder examinations. An FTRCT was defined as a discontinuity in the tendon or increased signal on T2-weighted images, isotense compared with fluid, extending from the articular to the bursal side of the tendon (CitationIanotti et al. 1991). The tear size in the sagittal plane (tendons involved) was determined in the oblique sagittal plane according to the classification of CitationThomazeau et al. (1997).

Statistics

Data are presented as median (range) for continuous or ordinal data and as number (%) for categorical data. The annual incidence of FTRCT was calculated using the total number of FTRCTs divided by 2 (the 2-year duration of the study) divided by the number of individuals in the same age group (18–75 years) living in northwestern Skåne (189,370 individuals). For the population at risk (age group 40–75 years), the denominator in the calculation was 118,302.

The 95% confidence interval (CI) of percentages was calculated using the Diagnostic Test Evaluation Calculator of the free-access Interactive Statistical Pages website. CI of the annual incidence was calculated using a web-based CI calculator (single incidence rate; Centre for Clinical Research and Biostatistics, the Chinese University of Hong Kong).

Ethics

This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund (registration number 2011/119).

Results

The PT examined 331 patients (60% men) at a median time of 14 (10–40) days after trauma. 72 patients were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria or declined to participate (). 259 participants made up the study group (65% men); median age was 51 (18–75) years. 88 participants with suspected FTRCT were diagnosed by MRI (n = 85) or ultrasound (n = 3, used because of claustrophobia). Patients with MRI-verified FTRCT were recommended to have arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. 47 of the 55 FTRCTs in group I underwent surgery at a median time of 28 (20–48) days after the trauma. All 47 patients had arthroscopy-verified FTRCTs with acute appearance. 8 patients declined surgery. The remaining 33 patients in group I had other lesions ().

Table 1. Diagnoses in group I who did not have acute full-thickness rotator cuff tear (n = 33)

Group II (other specific diagnoses) comprised 120 patients ().

Table 2. Diagnoses in group II (other specific diagnoses) (n = 120)

Group III (sprain) comprised 51 patients. 20 of them rated their shoulder function to be greater than 80%, and they were assumed not to have FTRCT. 7 patients could not be reached by telephone, were contacted by mail, and were encouraged to return for an update clinical examination if they still felt shoulder discomfort. None of them returned during the first 16 months after enrollment in the study, and they were considered not to have FTRCT. 24 patients rated their shoulder function to be less than 80% and were examined by a shoulder surgeon. MRI was performed in all but 3 patients; 5 patients were diagnosed with FTRCT.

The estimated population-based incidence of acute FTRCT was 16 (CI: 11–23) per 105 inhabitants for the age group 18–75 years. The annual incidence of FTRCT for the population at risk (aged 40–75 years) was 25 (CI: 18–36) per 105 inhabitants. The prevalence of acute FTRCT in the study group was 60/259 (23%, CI: 18–28)

The most common lesion was a combined subscapularis and supraspinatus tendon tear, followed by an isolated subscapularis tear (). The subscapularis tendon was involved in 38 of 60 of the rotator cuff tears (63%, CI: 52–76). 36 of the 60 patients (60%, CI: 48–72) had a FTRCT that involved 2 or more tendons.

Table 3. Distribution of the configurations of all MRI-verified full-thickness rotator cuff tears

The injury mechanism included fall from the same level (63%) followed by fall from a height (20%) and no fall (17%). 21% were sports-related injuries, which were mainly caused by skiing. Of the 259 participants, 54% suffered from direct trauma to the shoulder, 30% from indirect trauma, 5% from combined trauma, and 11% were unknown. The same pattern was also seen in the FTRCT patients. 30 patients had direct trauma, 19 had indirect trauma, and 3 had combined trauma. The dominant side was affected in 40 of the 60 FTRCTs.

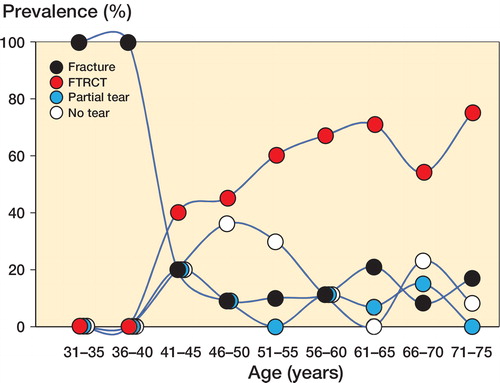

Occult fractures were more common in younger patients, while FTRCTs were more common in older patients. The majority of those who had FTRCTs were males (n = 49, 82%) ().

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report in the literature to define a population-based incidence of acute FTRCTs. We found that acute FTRCTs were common in the general population, with an annual incidence of 25 per 105 of the population at risk. A medium-sized hospital such as ours, with a catchment area of about one-quarter of a million, may diagnose 30 acute FTRCTs annually where surgical intervention is indicated. Sorensen et al. (2007) described a prevalence of 32% in their study population, which contrasts with the 23% found in the present study. The wider inclusion criteria in our study may explain the lower prevalence in our cohort. If we had excluded group II (other specific diagnoses) from our study, the prevalence would have increased to 43%.

The predominance of males in the FTRCT group (82%), compared to 65% in the study cohort, raises many questions. Firstly, this skewed distribution has not been seen with degenerative tears, where there has been an equal male-to-female ratio (CitationYamaguchi et al. 2006, CitationYamamoto et al. 2010). Even so, this finding is not new. A systematic review has shown that 77% of those with acute traumatic FTRCTs were males (CitationMall et al. 2013). Other tendon ruptures show similar male predominance. In a recent study, CitationVosseller et al. (2013) found a male predominance of 84% in patients with Achilles tendon tears. Distal biceps tears are even more rare in the female population (CitationSafran and Graham 2002). This cannot only be explained by the majority of traumas occurring in males. Sex-related differences in muscle strength and tendon quality, injury mechanism, and physical constitution may be other causal factors.

There is consensus concerning the association between advancing age and increasing prevalence of rotator cuff tears. In an MRI study investigating asymptomatic individuals, CitationSher et al. (1995) found a prevalence of FTRCT of 28% in their study population over 60 years and a 4% prevalence in individuals aged 60 years or younger. In a natural history study, CitationYamamoto et al. (2010) found an FTRCT prevalence of 21%, which increased to 45% in patients older than 70 years. The median age of the patients with FTRCTs in our study was 60 years, which is similar to that in the studies by CitationBjornsson et al. (2011) and CitationIde et al. (2007), who also investigated acute tears following shoulder trauma.

The size and location of rotator cuff tears differ in degenerative and acute traumatic tears (CitationMall et al. 2013). The MOON (Multicenter Orthopedic Outcomes Network) Shoulder Group (CitationHarris et al. 2012) reported a single-tendon rate of 71% (supraspinatus). In contrast, we found larger tears and single-tendon tears in only 42% of our patients. The MOON Shoulder Group also reported a 2% rate for subscapularis involvement (compared with 63% in our study). This supports the finding that acute tears are usually larger than degenerative tears, and are more likely to involve the subscapularis tendon.

The difficulty of and the controversy concerning the definition of acute rotator cuff tears may explain our limited knowledge in this topic. Like other authors (CitationLahteenmaki et al. 2006, CitationBjornsson et al. 2011, CitationHantes et al. 2011, CitationPetersen and Murphy 2011), we have defined acute tears as tears that (after a shoulder trauma) cause sudden onset of symptoms such as acute pain and limitation of active forward elevation or abduction in a patient with no ongoing shoulder disability. From different natural history studies, the reported prevalence of asymptomatic rotator cuff tears has varied from from 6% to 34% with increasing age (CitationMoosmayer et al. 2010). As these patients are asymptomatic, they would fit into the acute tear definition. Thus, some of our patients may have had a lesion that could not be diagnosed without pre-injury MRI. However, during surgery, all of the tears appeared to be acute.

The present study had other limitations. Firstly, we did not obtain MRI scans from all the patients, as the MRI resources at our hospital are limited. Furthermore, it is possible that the PT falsely classified some patients as having healthy tendons, which would have reduced the incidence calculated. Finally, we only studied those who sought medical advice. It is possible that there were patients with acute rotator cuff tears who did not ask for medical advice, and such patients would not have been included in the present study.

In summary, we found that acute FTRCT is common in the male population following simple falls, with an annual incidence of 25 per 105 of the population at risk. These tears are usually large, and involve the subscapularis tendon in almost two-thirds of cases.

KEA participated in the design of the study, prepared databases, carried out the calculations, and wrote the first draft. FA contributed to the statistical analysis and revision of the manuscript. KL supervised the study, participated in the design, and helped to draft the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

We thank physiotherapists Madelaine Andersson and Anna Lönnberg for performing physical examinations and monitoring the study, and Torsten Boegård for MRI reviews and radiological advice. The study was supported by grants from the Stig and Ragna Gorthon Research Foundation and the Thelma Zoega Foundation.

No competing interests declared.

- Bak K, Sorensen AK, Jorgensen U. The value of clinical tests in acute full-thickness tears of the supraspinatus tendon: does a subacromial lidocaine injection help in the clinical diagnosis? A prospective study. Arthroscopy 2010; 26: 734–42.

- Bassett RW, Cofield RH. Acute tears of the rotator cuff. The timing of surgical repair. Clin Orthop 1983; (175): 613–8.

- Benson RT, McDonnell SM, Knowles HJ, Rees JL, Carr AJ, Hulley PA. Tendinopathy and tears of the rotator cuff are associated with hypoxia and apoptosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92: 448–53.

- Bjornsson HC, Norlin R, Johansson K, Adolfsson LE. The influence of age, delay of repair, and tendon involvement in acute rotator cuff tears: structural and clinical outcomes after repair of 42 shoulders. Acta Orthop 2011;82:187–192.

- Codman EA. Rupture of the supraspinatus tendon 1911. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1990; (254): 3–26.

- Codman EA, Akerson IB. The Pathology associated with rupture of the supraspinatus tendon. Ann Surg 1931; 93(1): 348–59.

- Duquin TR, Buyea C, Bisson LJ. Which method of rotator cuff repair leads to the highest rate of structural healing? A systematic review. Am J Sports Med 2010; 38: 835–41.

- Fukuda H. Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears: A modern view on Codman’s classic. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2000; 9: 163–8.

- Hantes ME, Karidakis GK, Vlychou M, et al. A comparison of early versus delayed repair of traumatic rotator cuff tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011; 19: 1766–70.

- Harris JD, Pedroza A, Jones GL. Predictors of pain and function in patients with symptomatic, atraumatic full-thickness rotator cuff tears: A time-zero analysis of a prospective patient cohort enrolled in a structured physical therapy program. Am J Sports Med 2012; 40: 359–66.

- Ianotti JP, Zlatkin MB, Esterhai JL, Kressel HY, Dalinka MK, Spindler KP. Magnetic resonance imaging of the shoulder. Sensitivity, specificity and predictive value. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1991; 73: 17–29.

- Ide J, Tokiyoshi A, Hirose J, Mizuta H. Arthroscopic repair of traumatic combined rotator cuff tears involving the subscapularis tendon. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89: 2378–88.

- Lahteenmaki HE, Virolainen P, Hiltunen A, Heikkila J, Nelimarkka OI. Results of early operative treatment of rotator cuff tears with acute symptoms. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2006; 15: 148–53.

- Lungo UG, Berton A, Papapietro N, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Epidemiology, genetics and biological factors of rotator cuff tears. Med Sport Sci 2012; 57: 1–9.

- Mall NA, Lee AS, Chahal J. An evidenced-based examination of the epidemiology and outcomes of traumatic rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy 2013; 29: 366–76.

- Moosmayer S, Tariq R, Stiris MG, Smith HJ. MRI of symptomatic and asymptomatic full-thickness rotator cuff tears. Acta Orthop 2010; 81: 361–6.

- Namdari S, Henn R F III, Green A. Traumatic anterosuperior rotator cuff tears: The outcome of open surgical repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008; 90: 1906–13.

- Oh JH, Kim JY, Lee HK, Choi JA. Classification and clinical significance of acromial spur in rotator cuff tear: heel-type spur and rotator cuff tear. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468: 1542–50.

- Perry SM, Getz CL, Soslowsky LJ. After rotator cuff tears, the remaining (intact) tendons are mechanically altered. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2009; 18: 52–7.

- Petersen SA, Murphy TP. The timing of rotator cuff repair for the restoration of function. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011; 20: 62–8.

- Razmjou H, Robarts S, Kennedy D, McKnight C, Macleod AM, Holtby R. Evaluation of an advanced-practice physical therapist in a specialty shoulder clinic: diagnostic agreement and effect on wait times. Physiother Can 2013; 65: 46–55.

- Safran MR, Graham SM. Distal biceps tendon ruptures. Incidence, demographics, and the effect of smoking. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002; 404: 275–83.

- Sher JS, Uribe JW, Posada A, Murphy BJ, Zlatkin MB. Abnormal findings on magnetic resonance imaging of asymptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995; 77: 10–15.

- Sorensen AK, Bak, Krarup AL, Thune CH, Nygaard M, Jorgensen U, et al. Acutev rotator cuff tear: Do we miss the early diagnosis? A prospective study showing a high incidence of rotator cuff tears after shoulder trauma. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007; 16: 174–80.

- Thomazeau H, Boukobza E, Morcet N, Chaperon J, Langlais F. Prediction of rotator cuff repair results by magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1997; 344: 275–83.

- Vosseller JT, Ellis SJ, Levine DS, et al. Achilles tendon rupture in women. Foot Ankle Int 2013; 34: 49–53.

- Yamaguchi K, Ditsios K, Middleton WD, Hildebolt CF, Galatz LM, Teefey SA. The demographic and morphological features of rotator cuff disease. A comparison of asymptomatic and symptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88: 1699–704.

- Yamamoto A, Takagishi K, Osawa T, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010; 19: 116–20.

- http://www.cct.cuhk.edu.hk/stat/confidence%20interval/CI%20for%20single%20rate.htm (Accessed on 7th December 2014). C.I. Calculator: Single Incidence Rate, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Centre for Clinical Research and Biostatistics.

- http://www.scb.se/en_/. National Population Registry, Statistics Sweden.

- http://www.statpages.org/confint.html (Accessed 26th August 2014). Exact Binomial and Poisson Confidence Intervals. Diagnostic Test Evaluation Calculator, The Interactive Statistical Pages website.