Abstract

Background and purpose — Avascular necrosis (AVN) is a major cause of disability after treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), leading to femoral head deformity, acetabular dysplasia, and osteoarthritis in adult life. Type-II AVN is characterized by retarded growth in the lateral aspect of the physis or by premature lateral fusion, which produces a valgus deformity of the head on the neck of the femur. We investigated the effect of medial percutaneous hemi-epiphysiodesis as a novel technique in the treatment of late-diagnosed type-II AVN.

Patients and methods — 9 patients (11 hips) with a diagnosis of type-II AVN who underwent medial percutaneous hemi-epiphysiodesis after the surgical treatment for DDH were included in the study. 10 patients (12 hips) with the same diagnosis but who did not undergo hemi-epiphysodesis were chosen as a control group. Preoperative and postoperative articulotrochanteric distances, head-shaft angles, CE (center-edge) angles, and physeal inclination angles were measured. The treatment group underwent medial hemi-epiphysodesis at a mean age of 8 years. The mean ages of the treatment group and the control group at final follow-up were 14 and 12 years respectively. The mean duration of follow-up was 5.7 years in the treatment group and 8.3 years in the control group.

Results — Preoperative articulotrochanteric distance, head-shaft angle, and functional outcome at the final follow-up assessment were similar in the 2 groups. However, preoperative and postoperative CE angles and physeal inclination angles differed significantly in the treatment group (p < 0.05). The final epiphyseal valgus angles were better in the treatment group than in the control group (p = 0.05). The treatment group improved after the operation.

Interpretation — Medial percutaneous epiphysiodesis performed through a mini-incision under fluoroscopic control is a worthwhile modality in terms of changing the valgus tilt of the femoral head.

Avascular necrosis (AVN) of the proximal femoral epiphysis is an iatrogenic complication of treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) (CitationDanielsson 2000, CitationDhar 2003, Domalzki and Synder 2004, CitationRoposch et al.2013). A late abnormality that may be the manifestation of the lateral portion of the capital femoral growth plate in type-II AVN alters the morphology of hip joint (CitationKalamchi and MacEwen 1980). When a progressive valgus deformity occurs in a patient with type-II AVN, problems associated with hip dysplasia may follow (CitationSiffert 1981, CitationCampbell and Tarlos 1990, CitationKim et al. 2000, CitationWu et al. 2010, CitationHerring 2014). Due to inadequate coverage, reduced contact area between acetabulum and femoral head leads to early secondary osteoarthritis (Aronson 1986, Inoue et al. 2000, CitationHerring 2014).

The treatment decision for type-II AVN is challenging. Procedures such as varus femoral osteotomy and redirectional acetabular osteotomy have been used with a view to preventing future degenerative disease. However, these procedures are technically difficult and may result in serious complications (CitationSiebenrock et al. 2013). On the other hand, as the main pathology is the growth disturbance at the lateral aspect of the femoral head, some form of arrest of the medial portion of the growth plate may be more logical in the treatment of type-II AVN (CitationHerring 2014). We analyzed the radiographic and clinical outcomes of 11 hips in 9 patients with late-diagnosed type-II AVN who underwent percutaneous hemi-epiphysiodesis of the femoral head.

Patients and methods

12 patients (11 of them girls; 14 hips) with a diagnosis of Kalamchi type-II AVN between 1996 and 2002 participated into the study after surgical treatment for DDH. Of these, 1 patient refused surgery and 2 did not appear for follow-up examinations. The remaining 9 patients (8 girls; 11 hips) constituted the treatment group of the study. As a control group, 10 consecutive patients (9 girls; 12 hips) with similar demographics who did not undergo medial hemi-epiphysiodesis were chosen from another clinic. The mean age of the treatment group at the time of operation was 9 years. The mean duration of follow-up was 5.7 years for the treatment group and 8.3 years for the control group. At the time of the final follow-up, the mean age of the treatment group was 14 years and the mean age of the control group was 12 years.

The diagnosis of AVN was done radiographically. Standard AP radiographs of the pelvis were taken with the patients placed supine and both legs in neutral position, to minimize the effect of rotation of the hip joints. Articulotrochanteric distance, head-shaft angle, center-edge (CE) angle, and physeal inclination angle were measured. Preoperative radiographic measurements refer to values before the initial hip surgery for DDH in both groups. Postoperative measurements refer to the final follow-up values after hemi-epiphysiodesis in the treatment group and to the final follow-up values after DDH surgery in the control group. All the measurements were performed in blind fashion. The interobserver variability was studied using 2 of the authors (BÖ and AR) and the intraobserver error was evaluated using 1 author (BÖ). To evaluate intra- and interobserver agreement, a 3 week interval separated the first and second measurements. Interobserver agreement was high in both the first and the second evaluation (Kendall tau-b, p < 0.001). Intraobserver agreement was also high (Kendall tau-b, p < 0.0001). We measured pelvic rotation and tilt by the method described by van der CitationBrom et al. (2011) to limit the systematic error in assessing the radiological measurements caused by pelvic misalignment. All the radiographs acquired were within approximately ± 4˚ rotation and ± 4˚ tilt intervals, which is considered acceptable. Clinical assessments at final follow-up were made according to McKay’s criteria (CitationMcKay 1974). Patient characteristics in both groups are given in and .

Table 1. Patient characteristics

Table 2. Radiological measurements

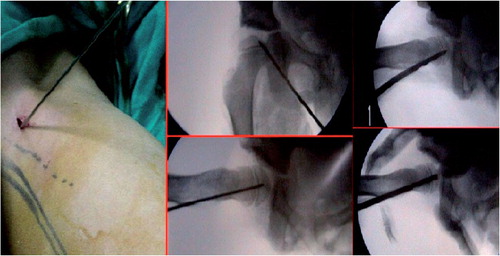

Surgical technique

All procedures were performed in supine position under general anesthesia. The hip joint was flexed and abducted to obtain a suitable entry point. Under image intensifier, the capital femoral physis was visualized and directly approached medially with the aid of a 1.2-mm Kirschner wire. The medial physis was almost totally destroyed by making 2 or 3 penetrations with the 3.5-mm drill in different directions, while being careful to leave the peripheral region intact in order not to cause collapse ().

The postoperative regimen included full weight bearing immediately. Patients were followed up clinically and radiographically for assessment of correction of the epiphyseal valgus deformity.

Statistics

Parametric tests were used to analyze variables with homogeneous variance and normal distribution, whereas non-parametric tests were used to analyze variables without homogeneous variance and normal distribution. In order to determine whether parametric tests could be used, we first confirmed the homogeneity of the variance and the normality of the distribution of the variables by using Levene’s test and a the Shapiro-Wilk W test, respectively. Independent-samples t-test and Mann-Whitney U-tests were used to compare continuous variables between independent groups where necessary, while Wilcoxon signed ranks test was used to compare discontinuous variables between dependent groups. Interobserver and intraobserver agreement was measured using the Kendall tau-b concordance coefficient.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 22.0 and PAST (paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis).

Results ( and )

There was no statistically significant difference when the treated hips were compared with the control group regarding preoperative articulotrochanteric distances and head-shaft angles at the final follow-up assessment. Preoperative and postoperative physeal inclination angles differed significantly in the treatment group (p = 0.002) ( and ). The treatment group also improved in terms of final epiphyseal valgus angles relative to the control group (p = 0.05).

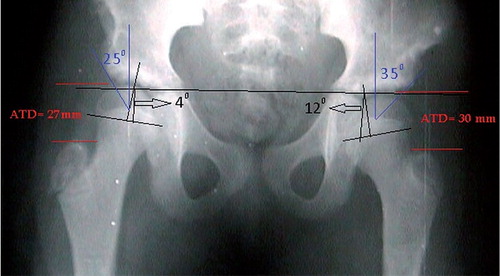

Figure 2. Preoperative epiphyseal and acetabular coverage angles in a bilateral type-II AVN patient.

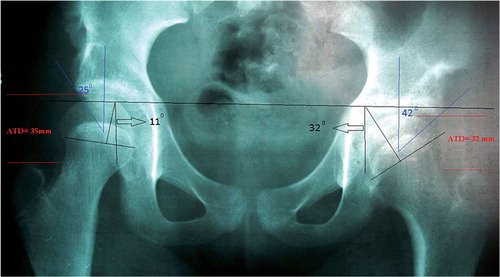

Figure 3. Postoperative epiphyseal and acetabular coverage angles in the same bilateral type-II AVN patient. There is significant correction on the left side.

Correction of the physeal valgus is expressed as the difference between the preoperative and postoperative physeal inclination angles. Alteration in the physeal inclination angle (from preoperatively to postoperatively) in the control group was 4° (0–7), and it was 10° (2–27) in the study group. Both groups showed statistically significant improvements in epiphyseal inclination angle. However, when the correction rate in the 2 groups was compared, it was borderline significant in the treatment group (p = 0.05).

There were no statistically significant differences in functional outcomes between the 2 groups. There were no major or minor complications related to the surgical procedure, including joint penetration and neurovascular injury.

Discussion

CitationKim et al. (2000) stated that only slightly more than half of type-II AVN patients end up with satisfactory results when left untreated. Traditionally partial hemi-epiphysiodesis is the treatment of choice when the epiphysis is partially affected in a growing child. This method is non-invasive, cheap, and effectively achieves partial closure of the hemiepiphysis (CitationBowen et al.1984). Well-designed animal and clinical trials have shown that using a combination of drills and high-speed burs effectively produce adequate epiphysiodesis (CitationCanalle et al. 1986, CitationAtar et al. 1991). In contrast, corrective osteotomies, which are used in the treatment of type-II AVN, address the resulting deformity rather than the partial growth disturbance occurring at the lateral side of the immature femoral head epiphysis. The main disadvantage of the osteotomies is that they treat a resulting deformity rather than trying to prevent it (CitationSiebenrock et al. 2013).

Furthermore, hospitalization, immobilization, and delayed weight bearing are other issues to be considered. When the deformity is discovered early, provided that the physis is still open and there is still potential growth, hemiephypysiodesis could be an alternative treatment modality.

In 1980, Kalamchi and MacEwen described a classification system emphasizing the growth disturbances associated with various degrees of physeal arrest. The most common type of growth disturbance in this classification system is type II, representing about one-third of cases. Also, the authors stated that type-II AVN may not be evident until the patient is more than 13 years old (mean: 9 years old). These authors stressed that “it may be difficult to identify this group early”. It may appear at any time until skeletal maturity (CitationDomzalski and Synder 2004). The mean age of our patients at operation was 8.

We do not know of any studies investigating the outcomes of percutaneous medial hemi-epiphysodesis in physeal valgus deformity after the treatment of DDH. We found that a medial percutaneous hemi-epiphysiodesis might solve the progressive valgus tilting of the femoral head. However, concerns about the altered hip mechanics in these patients should be kept in mind. Despite this operation being effective in changing the epiphyseal slope angle, long-term follow-up is needed because there is no evidence to suggest that it also improves outcome in hip dysplasia.

Our findings suggest that after the surgical insult on the medial epiphysis, adequate growth retardation is obtained to provide symmetrical epiphyseal growth retardation on both sides of the plate. Thus, favorable outcomes can be obtained even though a complete bony union cannot be formed. We can speculate that all our patients had enough remaining growth potential for satisfactory correction with medial hemi-epiphysiodesis to be achieved. Furthermore, as the proximal femoral physis is responsible for only about one-third of the growth of the femur, leg length discrepancy is not an important issue when hemi-epiphysodesis is performed.

None of our patients in the treatment group presented varus tilt of the femoral physis. However, over- or undercorrection of the deformity should be a matter of concern in younger patients. CitationRoposch et al. (2013) reported that osteonecrosis of the femoral head inhibited acetabular remodeling. We did not obtain substantial differences in terms of correction of femoral shaft angle, but we were able to improve the coverage of the femoral heads.

We did not observe complete radiographic osseous bridging in our patients at follow-up. In addition, substantial osseous bridging across the superior portion of the physeal plate could not be clearly identified in many hips with type-II AVN. Therefore, the procedure described here is able to correct the valgus deformity by providing growth disturbance at the medial side rather than by resulting in osseous bridging.

Our study had several limitations. The sample size was small. Also, the learning curve should be considered. Finally, the long-term outcome of the procedure is unknown.

The procedure we describe is technically demanding, with a risk of complications such as joint penetration and neurovascular injury. Because the growth plates are not perfectly flat, there is a technical challenge in making sure that the tip of the tool is at the growth plate and remains there. The surgeon should be careful not to inadvertently enter the joint space.

We believe that the advantages of the procedure far outweigh the risks, and we suggest that it should be an alternative treatment modality for physeal valgus deformity due to type-II AVN. Furthermore, performing a medial epiphysiodesis does not complicate subsequent surgical corrections.

We thank Prof. Ali Bicimoglu for his valuable contributions and for help in drawing up the control group of this study.

HA: conception of the study, interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation. BÖ and CK: data processing, interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation. AR: statistical analysis and manuscript preparation. OK: conception of study and interpretation of data.

No competing interests declared.

- Atar D, Lehman WB, Grant AD, Strongwater A. Percutaneus epiphysiodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991; 73(1): 173.

- Bowen JR, Johnson WJ. Percutaneous epiphysiodesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1984; (190); 170–173.

- Campbell P, Tarlos SD. Lateral tethering of the proximal femoral physis complicating the treatment of congenital hip dysplasia. J Pediat Orthop 1990; 10: 6–8

- Canalle ST, Russell T A Holcomb RL. Percutaneous epiphysiodesis: experimental study and preliminary clinical results. J Pediatr Orthop 1986; 6(2): 150–6.

- Danielsson L. Late-diagnosed DDH: A prospective 11-year follow-up of 71 consecutive patients (75 hips). Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71(3): 232–42.

- Dhar S Developmental dysplasia of the hip-Management between 6 months and three years of life. Indian J Orthop 2003; 37834: 227–232.

- Domzalski M, Synder M. Avascular necrosis after surgical treatment for development dysplasia of the hip. Int Orthop 2004; 28: 65–8.

- Herring JA. Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. In: Tachdjian’s Pediatric Orthopeedics. Fifth edition. Saunders, Elsevier Inc. 2014; 1: 521–523

- Kalamchi A, MacEwen G D Avascular necrosis following treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1980; 62: 876–88.

- Kim HW, Morcuende JA, Dolan LA, Weinstein SL. Acetabular development in developmental dysplasia of the hip complicated by lateral growth disturbance of the capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000; 82: 1692–700.

- McKay DW. A comparison of the innominate and pericapsular osteotomy in the treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. Clin Orthop 1974; (98): 124–32.

- Roposch A, Ridout D, Protopapa E, Nicolaeu N, Gelfer Y. Osteonecrosis complicating developmental dysplasia of the hip compromises subsequent acetabular remodeling? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471(7): 2318–26.

- Siebenrock KA, Steppacher SD, Alberts CE, et al. Diagnosis and management of developmental dysplasia of the hip from triradiate closure through young adulthood. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95(8): 749–55.

- Siffert RS. Patterns of deformity of the developing hip. Clin Orthop 1981; (160): 14–29.

- Van der Brom MJ, Groote ME, Vincken KI, Beek FJ, Bartels LW. Pelvic rotation and tilt can cause misinterpretation of the acetabular index measured on radiographs. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469: 1743–9.

- Wu KW, Wang TM, Huang SC, Kuo KN, Chen CW. Analysis of osteonecrosis following Pemberton acetabuloplasty in developmental dysplasia of the hip: long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92(11): 2083–94.