Abstract

Background and purpose — Virtual-reality (VR) simulation in orthopedic training is still in its infancy, and much of the work has been focused on arthroscopy. We evaluated the construct validity of a new VR trauma simulator for performing dynamic hip screw (DHS) fixation of a trochanteric femoral fracture.

Patients and methods — 30 volunteers were divided into 3 groups according to the number of postgraduate (PG) years and the amount of clinical experience: novice (1–4 PG years; less than 10 DHS procedures); intermediate (5–12 PG years; 10–100 procedures); expert (> 12 PG years; > 100 procedures). Each participant performed a DHS procedure and objective performance metrics were recorded. These data were analyzed with each performance metric taken as the dependent variable in 3 regression models.

Results — There were statistically significant differences in performance between groups for (1) number of attempts at guide-wire insertion, (2) total fluoroscopy time, (3) tip-apex distance, (4) probability of screw cutout, and (5) overall simulator score. The intermediate group performed the procedure most quickly, with the lowest fluoroscopy time, the lowest tip-apex distance, the lowest probability of cutout, and the highest simulator score, which correlated with their frequency of exposure to running the trauma lists for hip fracture surgery.

Interpretation — This study demonstrates the construct validity of a haptic VR trauma simulator with surgeons undertaking the procedure most frequently performing best on the simulator. VR simulation may be a means of addressing restrictions on working hours and allows trainees to practice technical tasks without putting patients at risk. The VR DHS simulator evaluated in this study may provide valid assessment of technical skill.

Surgical trainees now have less dedicated operating time than their predecessors had, but they are required to reach the same level of competency within a shorter overall training period. It has been calculated that a surgeon finishing his or her training in the UK will have had a greater than 80% reduction in the number of hours of surgical training, down from 30,000 to 6,000 (CitationChikwe et al. 2004). There is a similar pattern elsewhere due to the European Working Time Directive. There is a need to evaluate alternative methods of training, and this is where simulation may have a role.

By its nature, virtual-reality (VR) simulation lends itself to those procedures that can be replicated on a 2-dimensional screen, such as arthroscopy. It can also be applied to procedures such as fracture fixation, where the fluoroscopic intraoperative images can also be recreated on a monitor. However, while there are several papers in the literature on arthroscopic simulation (CitationHowells et al. 2008; CitationBayona et al. 2014), there is little on orthopedic trauma simulation (CitationBlyth et al. 2008, CitationFroelich et al. 2011).

Most recently, CitationPedersen et al. (2014) demonstrated construct validity between novice and experienced surgeons looking at 3 orthopedic trauma modules using the TraumaVision simulator. However, this study did not assess the construct validity of the only clinically validated performance metric for the dynamic hip screw (DHS) procedure, which is the tip-apex distance (TAD) established by CitationBaumgaertner et al. (1995). In addition, the study only showed a difference between novices and experts, but there was no middle-grade training group recruited. After all, it is the middle-grade trainees who will be expected to perform DHS procedures as the primary surgeon while the senior experts supervise them and the junior novices act as assistants.

The TraumaVision simulator (Swemac Orthopaedics, Linkoping, Sweden) is a VR simulator with haptic feedback that aims to recreate the sensation of drilling and reaming cortical and cancellous bone. In this system, various preloaded trauma modules are available. The fixed-angle sliding screw device module (cannulated/ dynamic hip screw (CHS/DHS)) for the fixation of femoral intertrochanteric fractures was chosen for our study.

We assessed the TraumaVision simulator for construct validity: i.e. the ability of the simulator to objectively differentiate between subjects with varying levels of expertise. This criterion was chosen because simulators must reliably discriminate between skill levels before they can be considered for training.

Material and methods

Sample population and stratification

30 postgraduate (PG) orthopedic trainees were recruited during their placement at Imperial NHS Hospitals Trust, and from formal teaching sessions at the department. They were divided into 3 groups of 10 participants each according to clinical experience (the number of DHS procedures performed independently) and years of postgraduate training (PG years). All the participants were practising at the hospital at the time of the study. Novices (1–4 PG years) had performed less than 10 DHS procedures; intermediates (5–12 PG years) had performed between 10 and 100 DHS procedures; and experts (> 12 PG years) had performed over 100 procedures. The level of clinical experience was confirmed by the participant’s Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Programme logbook, which outlined the number of operations observed, assisted, and performed. Median age was 32 (25–40) years with 25 male participants and 5 female participants, and with 28 being right-handed. The mean clinical experience for the 3 groups is summarized in .

Table 1. The clinical experience of the 3 study groups. Values are average number of operations (rounded down)

Equipment

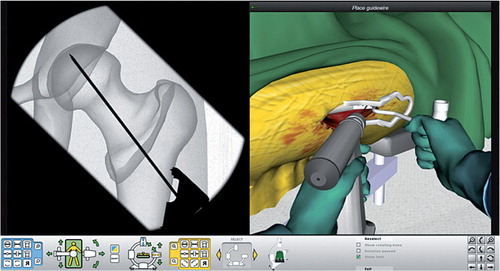

The TraumaVision simulator is controlled via a stylus, which is manipulated in space and used to represent a guide-wire and fixed-angle guide, cannulated reamer, drill, depth gauge, and screwdriver on the computer screen (). This is attached to a Geomagic Touch X (Geomagic, Cary, NC) haptic device that provides positional sensing and high-fidelity force-feedback output (maximum exertable force: 7.9 N; continuous exertable force (24 h): 1.75 N). The haptic feedback allows users to feel resistance when in contact with tissue and bone, to try to recreate realistic feedback, and it even permits tactile differentiation between cortical and cancellous bone.

Metrics

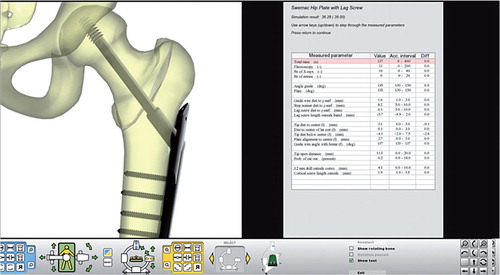

The participants watched a 4-minute video in which they were taken through each step. The simulator records 16 objective performance metrics and then calculates a subjectively weighted total score based on a composite of these metrics (). The most pertinent metrics for this study consisted of 6 indices: (1) number of attempts at guide-wire insertion (n); (2) total time taken (s); (3) total fluoroscopy time (s); (4) tip-apex distance (mm); (5) probability of cutout (%); and (6) overall simulator score (out of 39).

A new attempt at guide-wire insertion was recorded each time the guide wire was withdrawn fully from the bone and reinserted. The probability of cutout was calculated according to Baumgaertner’s curve (CitationBaumgaertner et al. 1995), the principal dependent variable of which was tip-apex distance from the isometric center of the femoral head.

Data analysis

Each performance metric was taken as the dependent variable in 3 regression models: (1) with grade as the independent variable, (2) with experience (number of procedures performed) as the independent variable, and (3) with both grade and experience included as independent variables. The number of procedures performed and probability of cutout variables were log-transformed, as they were negatively skewed and strictly positive. Normal linear regression was used in all cases except where “attempts” was the dependent variable, for which a Poisson regression was fitted. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The data were analyzed using SPSS and R software.

Ethics

The study was approved by Imperial College Medical Education Ethics Committee (MEEC1213-17).

Results

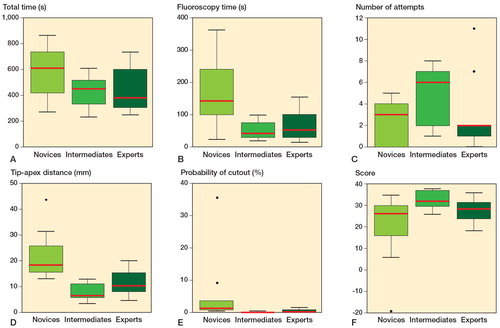

Outcomes for each objective performance metric by grade are shown in , and they are ranked in . This exploratory analysis indicated that 1 of the novice group was an outlier. All regression models were therefore run both with and without this observation; there were no substantial changes in the conclusions. The results given include the outlier.

Figure 3. Box-and-whisker plots of performance metrics of the 3 study groups. The box shows the upper and lower quartile, the red line is the median, the whiskers show the upper and lower limits. The individual dots signify outliers that lie outside the expected range. Intermediates consistently outperformed both novices and experts in all performance metrics except for number of attempts. Experts outperformed novices in all metrics.

Table 2. Group ranking of objective performance. Values are mean (SD) [95% CI]

Total time taken (s)

On average, intermediates took the least amount of time to complete the procedure, followed by experts, and then novices. The intermediates had the lowest spread about the mean (). The novices had the largest range, and also a 50% greater median than the experts. The difference in time taken between the groups was not statistically significant; nor was the effect of experience.

Total fluoroscopy time (s)

Conversely, there was a statistically significant difference in the total fluoroscopy time between intermediates and novices (p = 0.001), and between experts and novices (p = 0.004), with intermediates taking the least time, followed by experts, and with novices taking the most. The intermediate group had the lowest median and spread, followed by the expert group, and the novice group had the most inconsistent outcomes ().

Number of attempts at guide-wire insertion

The novices had the fewest attempts on average, then the experts, and the intermediates had the most. With respect to distribution (), the experts had the least spread. Both intermediates and novices shared a median value, but had inverted lower and upper quartile distribution, so that the intermediates had the highest mean number of attempts. There was a statistically significant difference in performance of attempts between groups (p < 0.04).

Tip-apex distance (mm)

There were statistically significant differences in tip-apex distance between groups (p < 0.001), and experience was a significant predictor (p < 0.001). Furthermore, there was a difference between intermediates and novices even after correcting for experience (p < 0.05). Intermediates had the lowest tip-apex distance, followed by experts, and then novices. The intermediate group was also the most consistent ().

Probability of cutout (%)

In keeping with the trend in tip-apex distance, the probability of percentage cutout followed the same pattern (). Intermediates had the lowest probability of cutout, followed by experts, and finally novices. Logarithmic conversion of probability of cutout indicated a statistically significant difference between intermediates and novices (p < 0.001), and between experts and novices (p < 0.001). Experience was also significant in the marginal model where experience was the only independent variable (p = 0.001).

Overall simulator score

The TraumaVision simulator assigns participants an overall score by recording 16 performance metrics and giving each a subjectively weighted rank, to give a final score out of 39. The higher the score, the better the perceived performance. Intermediates scored the highest on average, followed by experts, and finally novices (). Intermediates had the highest average score and also the smallest spread around the mean, with experts close behind (). However, the novice group was the only one with outliers, and had the lowest median with the largest spread. Statistical significance was only found between the intermediate group and their experience against the baseline if taken as independent variables (p = 0.01 and p = 0.02, respectively).

We established construct validity for 5 out of 6 objective performance metrics, to distinguish between simulation scores and level of training. Moreover, the simulator correctly identified those surgeons who currently perform many DHS procedures (the intermediates), followed by those supervising but not necessarily operating (the experts), followed by those with the least experience (the novices).

Discussion

Objective performance metrics analysis

The study showed that intermediate-grade surgeons generally performed best technically, followed by experts and then novices. The 3 groups showed statistically significant differences in performance in 5 out of the 6 objective metrics. Furthermore, intermediates also had the smallest spread around the mean, suggesting more consistent performance. Factors determining clinical success—other than measuring technical skills on this simulator—were taken into account, but in this study we minimized bias and standardized the exercise to validate the simulator.

One plausible reason for intermediates performing highly on the measured metrics could be that in practice, intermediates perform the procedure most frequently of all 3 groups. In our institution, DHS procedures are performed by resident level trainees, often with experts (i.e. attending surgeons) unscrubbed in theater or available nearby in case there are complications. The frequency of DHS surgery on trauma operating lists ensures constant exposure and repeated practice, as reported by CitationEricsson et al. (1993). While experts have amassed the most amount of clinical experience in performing DHS operations since graduating, as seen in , once they have completed their formal training they perform less DHS operations and may undergo a certain amount of skills decay.

It was not surprising that novices had the fewest number of attempts at guide-wire insertion, and intermediates had the most. Novices lack experience in choosing the most appropriate starting point for their guide wire, and may not be aware of the concept of the tip-apex distance. Furthermore, novices may not have developed the visuo-spatial awareness required for fluoroscopic tasks and may have prioritized fewer attempts over optimal guide-wire positioning as a marker of success. Novices also had the longest fluoroscopy times (over 3 times more than intermediates), which affected the total procedural time, and this would increase the patient’s exposure to radiation in the clinical setting.

Conversely, the intermediates were the most exacting in achieving the optimal tip-apex distance—and if not satisfied with the initial attempt, they repositioned the guide wire as many times as necessary. This did not significantly affect the length of the procedure, however. Their visuo-spatial awareness of guide-wire positioning is likely to be more developed as a reflection of their constant clinical exposure.

However, it is important to note that all of the participants in the intermediate and expert groups achieved a tip-apex distance less than the clinically acceptable 25 mm (CitationBaumgaertner et al. 1995), with very low rates of failure expected. This is the key clinical determinant, and it is not known whether the other differences in performance metrics have any clinical relevance. It is also unknown how performance on a simulator correlates with actual clinical performance.

Total procedural time was the only objective metric that was not statistically significantly different between groups. This may have been because the procedure was too short to allow differences to be registered, such that a ceiling effect was introduced. One weakness of this study (and of the simulator) is that it is not possible to test fracture reduction, and this may well be the major determinant of successful outcomes for trochanteric femoral fractures. We hypothesize that this is where the greater experience and skill of the senior surgeon would come into play, and that adding this in would give a truer test of performance.

Comparison with the literature

CitationBlyth et al. (2008) developed a more basic desktop-based VR simulation for the manual positioning of a DHS using only a mouse and key strokes. However, not all the steps had to be performed by the user, they did not perform any of the psycho-motor movements required in surgery, and there was no haptic feedback. The only study in the literature that was similar to our study was performed by CitationFroelich et al. (2011), who assessed the construct validity of a precursor of the TraumaVision simulator using 15 residents with mixed experience. However, only the initial few steps were tested, with guide-wire insertion and use of the cannulated reamer. They found no difference between the groups concerning time taken and tip-apex distance. As in our findings, they did show that novice residents had fewer attempts at placing the guide wire, which they attributed to “a willingness to accept or inability to recognise a less than optimal starting point” when compared with the more senior groups. Similarly, they also found that the more senior group of residents used less fluoroscopy and they were more comfortable with the anticipated final position of the wire.

The study by CitationFroelich et al. (2011) had a few limitations, however. Due to time constraints and limited access to the simulator, novice and senior residents performed the procedure 6 and 4 consecutive times, respectively. This may have inadvertently introduced bias and affected the final results, as learning may have taken place as the participants became increasingly familiar with the simulator. Similarly, CitationPedersen et al. (2014) allowed their participants to have a 20-minute warm-up time but did not account for the inevitable training or learning effect before recording the results of the formal assessment. Since each participant learns at a different pace, a 20-minute warm-up time does not guarantee a level playing field before formal assessment. Only one metric (percentage of maximum score) was statistically significant, but in our study we have demonstrated significant differences in 5 out of the same 6 metrics after adding an intermediate group and with stricter standardization—such as no warm-up time.

Future work

Future studies looking at larger population samples may help to inform us of the average time and number of attempts required by a trainee to achieve competence. Exposure to video gaming in postgraduate groups may also lead to better performance on the simulator. However, a correlation between video gaming and performance on the same VR DHS simulator has only been demonstrated in medical students, by CitationKhatri et al. (2014).

Conclusion

This study proves construct validity of a haptic VR DHS trauma simulator. The results show that the surgeons who perform this procedure most frequently also perform best on the simulator. Simulation has the potential to be an important adjunct to traditional orthopedic training. The detailed level of objective feedback provided by the simulator is not available in the operating theater, and provides precise guidance on areas for improvement. It may also facilitate individualized learning and could be used in the assessment and selection of future trauma surgeons if appropriately validated.

KA and KS contributed equally (joint first authors). KA, KS, JC, NS, and CG devised the study. KA and KS devised the methodology, performed data collection, and wrote the drafts. MS and KS collated and analyzed the data. JC, NS, and CG supervised the study and reviewed the final draft.

No competing interests declared.

- Bayona S, Akhtar K, Gupte C, Emery RJ, Dodds AL, Bello F. Assessing performance in shoulder arthroscopy: The Imperial Global Arthroscopy Rating Scale (IGARS). J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96(13): e112.

- Baumgaertner MR, Curtin SL, Lindskog DM, Keggi JM. The value of the tip-apex distance in predicting failure of fixation of peritrochanteric fractures of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995; 77(7): 1058-64.

- Blyth P, Stott NS, Anderson IA. Virtual reality assessment of technical skill using the Bonedoc DHS simulator. Injury 2008; 39 (10): 1127-33.

- Chikwe J, de Souza AC, Pepper JR. No time to train the surgeons. BMJ 2004; 328 (7437): 418-9.

- Ericsson KA, Krampe RT, Tesch-Romer C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol Rev 1993; 100(3): 363– 406.

- Froelich JM, Milbrandt JC, Novicoff WM, Saleh KJ, Allan DG. Surgical simulators and hip fractures: a role in residency training? J Surg Educ 2011; 68 (4): 298-302.

- Howells NR, Gill HS, Carr AJ, Price AJ, Rees JL. Transferring simulated arthroscopic skills to the operating theatre: a randomised blinded study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90 (4): 494-9.

- Khatri C, Sugand K, Anjum S, Vivekanantham S, Akhtar K, Gupte C. Does video gaming affect orthopaedic skills acquisition? A prospective cohort-study. PLoS ONE 2014; 9 (10): e110212.

- Pedersen P, Palm H, Ringsted C, Konge L. Virtual-reality simulation to assess performance in hip fracture surgery. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (4): 403-7.