Abstract

Background and purpose — Growth modulation with a medial malleolar screw is used to correct ankle valgus deformity in children with a wide spectrum of underlying etiologies. It is unclear whether the etiology of the deformity affects the angular correction rate with this procedure.

Patients and methods — 79 children (20 girls) with ankle valgus deformity had growth modulation by a medial malleolar screw (125 ankles). To be included, patients had to have undergone screw removal at the time of skeletal maturity or deformity correction, or a minimum follow-up of 18 months, and consistent radiographs preoperatively and at the time of screw removal and/or follow-up. The patients were assigned to 1 of 7 groups according to their underlying diagnoses. The lateral distal tibial angle (LDTA) was analyzed preoperatively, at screw removal, and at follow-up.

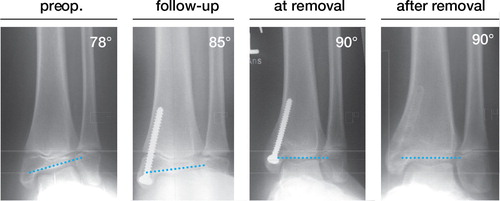

Results — Mean age at operation was 11.7 (7.4–16.5) years. The average lateral distal tibial angle normalized from 80° (67–85) preoperatively to 89° (73–97) at screw removal. The screws were removed after an average time of 18 (6–46) months, according to an average rate of correction of 0.65° (0.1–2.2) per month. No significant differences in the correction rate per month were found between the groups (p = 0.3).

Interpretation — Growth modulation with a medial malleolar screw is effective for the treatment of ankle valgus deformity in patients with a wide spectrum of underlying diagnoses. The individual etiology of the ankle valgus does not appear to affect the correction rate after growth modulation. Thus, the optimal timing of growth modulation mainly depends on the remaining individual growth and on the extent of the deformity.

Ankle valgus deformity may occur in children with various disorders. This deformity usually progresses and causes dynamic malalignment and abnormal loading of the joints of the lower extremity. Associated deformities such as planovalgus feet or hallux valgus occur and they may cause significant problems with gait, shoe wear, and brace fit.

Ankle valgus is most often seen in children with neuromuscular disorders such as myelomeningocele (MMC) (CitationDias 1978, CitationMalhotra et al. 1984), poliomyelitis, and cerebral palsy (CP) (CitationMakin 1965), and it may be overlooked in the presence of concurrent foot deformities. It also occurs in children with postaxial hypoplasia, clubfoot (CitationCoventry and Johnson 1952, CitationThompson et al. 1957, CitationBohne and Root 1977), pseudarthrosis of the fibula (CitationLangenskiöld 1967, CitationDooley et al. 1974, CitationHsu et al. 1974), or hereditary multiple exostoses (HME) (CitationRupprecht et al. 2011, Citation2014, CitationDriscoll et al. 2013). Regardless of these different etiologies, the main goals of treatment are correction of the ankle valgus, prevention of further deformities, resumption of normal activities, and prevention of degenerative changes. Apart from nonoperative management with braces in mild cases, there are many surgical procedures—ranging from a tibial supramalleolar osteotomy, distal tibial wave osteotomy (CitationSharrard and Grosfield 1968, CitationKumar et al. 1990, CitationAbraham et al. 1996), transepiphyseal osteotomy of the distal tibia (CitationLubicky and Altiok 2001), to modulation of growth with a medial malleolar screw or staple (CitationBeals and Skyhar 1984, CitationDavids et al. 1997, CitationRupprecht et al. 2011, CitationStevens et al. 2011).

Until now, it has been unclear whether the underlying diagnosis affects the treatment and results of ankle valgus deformity correction by growth modulation with a medial malleolar screw. We therefore examined the effectiveness of this procedure, the complications associated with it, and the angular correction rate per month with respect to the underlying diagnoses.

Patients and methods

The inclusion criteria in this retrospective study were (1) that the child had had a temporary growth modulation with a medial malleolar screw for the treatment of an ankle valgus; (2) that the child had had screw removal (SR) at the time of skeletal maturity or correction of the deformity, or a minimum postoperative follow-up time of 18 months; and (3) that there were consistent radiographs (standing anteroposterior films of the entire lower leg including the ankle and knee) preoperatively and postoperatively, and also at the time of screw removal and follow-up. Patients with an ankle valgus of < 5° were excluded. If it was unclear whether there was enough remaining growth potential for successful modulation of growth, the skeletal age was analyzed from a radiograph of the left hand. In patients who were close to skeletal maturity (with at least 1 year of growth remaining), no growth modulation was performed. Patients were evaluated clinically and with serial plain radiographs every 3–6 months until they reached skeletal maturity.

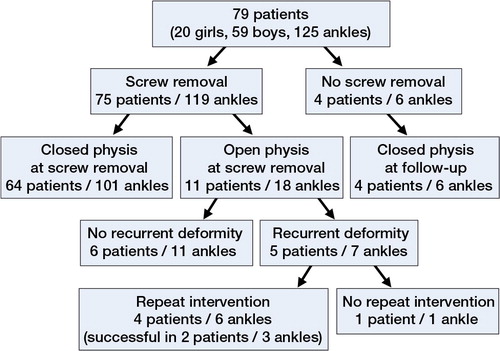

From January 2002 to July 2013, 79 children (20 girls and 59 boys) fulfilled the inclusion criteria (). The average age at the time of surgery was 11.7 (7.4–16.5) years. Growth modulation with a medial malleolar screw was performed on 125 ankles—bilaterally in 46 children and on 1 side in 33 children.

Group assignment

The patients were assigned to 7 different groups according to their diagnosis. Clubfoot was the most common diagnosis (21 children) (). In the “other” group, 3 patients had Down’s syndrome, 2 had scleroderma, and 1 had mucopolysaccharidosis. In 2 other children, the valgus deformity occurred after trauma, and in 1 case it occurred as a result of osteomyelitis.

Table 1. Group assignment

Surgical procedure

Growth modulation with a medial malleolar screw was performed in a standardized manner (CitationRupprecht et al. 2011). In the early years of the study period, a non-cannulated 4.5-mm fully threaded screw was used. Nowadays, we prefer the cannulated 4.5-mm fully threaded screw. With the child supine under general anesthesia, after a small skin incision a 1.2-mm K-wire is introduced into the central portion of the medial malleolus and advanced across the physis into the metaphysis. The position is controlled with fluoroscopy. The non-cannulated screw is introduced after drilling parallel to the K-wire, up to the depth of the desired screw length (usually 4–6.5 cm). The cannulated screw is introduced after pre-drilling over the guide wire. The head of the screw must be flush with the surface of the medial malleolus; the lateral cortex of the tibia should not be engaged by the screw. The screws were removed at maturity, or when the ankle valgus deformity was fully corrected.

Radiographic analysis

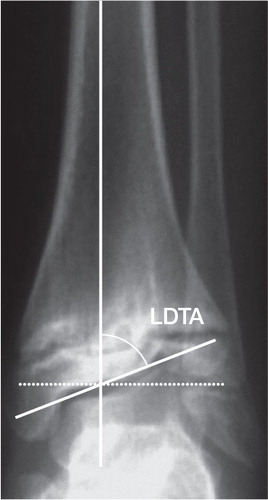

All radiographs were obtained under weight bearing. To identify ankle orientation, the lateral distal tibial angle (LDTA) was analyzed preoperatively, at the time of screw removal, and at follow-up. The lateral distal tibial angle was determined by measuring the angle created by the intersection of the central axis of the tibia and a second line drawn across the epiphyseal surface of the distal tibia (). To determine the remaining growth potential at the time of screw removal and at follow-up, the distal tibial physis was evaluated for signs of closure. Ossification of the distal tibial physis begins laterally. If lateral ossification becomes visible, no substantial growth remains, precluding a rebound phenomenon.

Statistics

Baseline characteristics of the participants are reported as median (range). Due to the presence of dependent measures taken in both sides of a child, we used linear mixed models for analysis. We set alpha = 0.05 as the level of significance. Pairwise comparisons between groups were conducted; if the global F-test of group mean differences was significant, no further alpha correction method was used. All analyses were performed using R software version 2.15, using the lme4 package for mixed models.

Results

No deep wound infections, pathological fractures, or neurovascular lesions were seen, and there were no implant failures. The average preoperative lateral distal tibial angle (from 125 ankle joints) was 80° (67–85). The preoperative ranges for the lateral distal tibial angle varied between the groups (). Patients with HME had statistically significant lower preoperative lateral distal tibial angle than patients in the idiopathic category or patients with clubfoot. In 79 children, the growth modulation was effective in correcting the valgus deformity. In 3 patients (1 with meningomyelocele, 1 with HME, and 1 with idiopathic ankle valgus), the correction was < 5°, most likely due to advanced skeletal age. Until screw removal, the lateral distal tibial angle was normalized to 89° (73–97). The screws were removed after an average time of 18 (6–46) months after the index procedure, according to an average rate of correction of 0.65° (0.1–2.2) per month (123 ankles). The highest correction rate per month was calculated for the patients with clubfoot (0.78°), and the lowest for patients with a meningomyelocele (0.38°). Regarding the correction rate per month, no statistically significant differences were found between the groups (p = 0.3). According to the age at the time of growth modulation, the correction rate per month varied from 0.52° (0.29–0.87) in children less than 10 years of age to 0.72° (0.1–1.67) in children between 13 and 14 years of age. These differences were not statistically significant.

Table 2. Results of radiographic analyses

At the time of screw removal, the distal tibial physis was either completely closed or ossified at the lateral aspect in 64 patients (101 ankles) (). At this stage, the deformity in 3 patients (6 ankles) was not fully corrected. 4 other skeletally mature patients (6 ankles) refused screw removal. 11 patients (18 ankles) were skeletally immature at the time of screw removal. These patients were evaluated until they reached skeletal maturity (mean follow-up after screw removal: 28 months). In 2 patients (1 patient with HME and 1 with clubfoot), an overcorrection into a mild varus deformity occurred. 5 patients (7 ankles) developed a recurrent valgus deformity. 4 of them had HME and 1 had clubfoot. In 4 patients, repeat growth modulation by a medial malleolar screw was performed successfully. In 1 patient, however, the remaining growth potential was insufficient for us to consider another guided growth procedure ().

Discussion

The etiology of ankle valgus in children is poorly understood. The pathophysiology is thought to be a relative shortening of the fibula (CitationWiltse 1972). The talus loses its lateral support and valgus ankle instability occurs, with abnormal loading conditions inhibiting growth of the lateral part of the distal tibial epiphysis (CitationWiltse 1972, CitationHsu et al. 1974, CitationTompkins et al. 2012).

Since the first report by CitationStevens and Belle (1997), growth modulation by use of a medial malleolar screw is known to be an effective treatment option for the treatment of ankle valgus deformity (CitationStevens and Belle 1997, CitationStevens et al. 2011) (). Nowadays, screws, tension band plates, and staples are used (CitationStevens et al. 2011, CitationTompkins et al. 2012, CitationDriscoll et al. 2014). To date, there have been no detailed analyses of the effectiveness of the growth modulation with a medial malleolar screw, focusing on the underlying etiology of ankle valgus deformity. As far as we know, we have reviewed the largest cohort of patients treated with this procedure.

Table 3. Literature review

Growth modulation with a medial malleolar screw was effective in 76 of our children. The underlying diagnoses had no statistically significant influence on the correction rate per month, and on final outcome. Patients with a clubfoot had the highest rates of correction per month (0.78°), and children with meningomyelocele had the lowest (0.38°). However, the individual rates within the groups vary from 0.1° to 2.2° per month.

CitationDriscoll et al. (2013) compared children with and without HME and reported inferior correction rates for patients with exostoses (0.37° vs. 0.51°). In contrast to this report, the correction rate in patients with HME in our series was 0.6°, as compared to an average of 0.65° per month in all patients. Similar rates were reported by CitationDavids et al. (1997) and CitationStevens et al. (2011). In both series, the most commonly associated diagnosis was clubfoot. In another series by CitationStevens and Belle (1997), they calculated an average angular correction of 10° in 4.4 (2.5–7.0) years, giving a correction per month of almost 0.2°. More than half of these patients (18 of 31) had a neuromuscular condition (e.g. cerebral palsy, myelodysplasia). This observation was confirmed in our series, since we calculated the lowest correction rates for children with myelomeningocele (0.39) and cerebral palsy (0.45). This finding is most probably due to the commonly reduced height of patients affected by a meningomyelocele and the reduced growth potential of the extremities involved. Unfortunately, in this retrospective review we had no detailed information about patients’ height at the time of surgery and follow-up. The angular correction rate per month was slightly increased in children close to puberty, but the individual variation in correction rate does not allow well-founded prediction on the basis of age.

The limitations of the present study include the retrospective design. There was no solid clinical outcome information such as complaints from the patients of their parents about visible deformity or change in orthotic tolerance, thus precluding objective comparison of the preoperative situation and the situation at follow-up. As the remaining growth potential is critical for the effectiveness of epiphyseodeses, the age of bone is an important factor. However, we used the chronological age, because the bone age was not available retrospectively. The major strength of the study was the complete long-term follow-up in a large group of patients.

In summary, growth modulation with a medial malleolar screw is effective for treatment of ankle valgus deformity in patients with a wide spectrum of underlying diagnoses. The individual etiology of the ankle valgus does not appear to influence the angular correction rate substantially after this procedure, although children with neuromuscular conditions had lower correction rates per month than children affected by clubfoot. The individual correction rates differed substantially and exceeded the variance within the groups. Thus, the optimal timing of the growth modulation for correction of an ankle valgus primarily depends on the remaining individual growth potential and the extent of the deformity.

MR and ASS: study design, collection and interpretation of data, and writing. SB and KR: collection of data. EV: statistical analysis and interpretation of data. RS: study design and correction of manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

- Abraham E, Lubicky J P , Songer M N, et al. Supramalleolar osteotomy for ankle valgus in myelomeningocele. J Pediatr Orthop 1996; 16: 774-781.

- Beals R K, Skyhar M. Growth and development of the tibia, fibula, and ankle joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1984; (182): 289-92.

- Bohne W H, Root L. Hypoplasia of the fibula. Clin Orthop 1977: (125): 107-12.

- Coventry M B, Johnson E WJr. Congenital absence of the fibula. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1952: 34-A: 1-55.

- Davids J R, Valadie A L, Ferguson R L, et al. Surgical management of ankle valgus in children: use of a transphyseal medial malleolar screw. J Pediatr Orthop 1997; 17: 3-8

- Dias L S. Ankle valgus in children with myelomeningocele. Dev Med Child Neurol 1978; 20: 627-33.

- Dooley B J, Menelaus M B, Melbourne, Paterson D C. Congenital pseudarthrosis and bowing of the fibula. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1974; 56-B(4): 739-43.

- Driscoll M, Linton J, Sullivan E, Scott A. Correction and recurrence of ankle valgus in skeletally immature patients with multiple hereditary exostoses. Foot Ankle Int 2013; 34(9): 1267-73.

- Driscoll M D, Linton J, Sullivan E, Scott A. Medial malleolar screw versus tension-band plate hemiepiphysiodesis for ankle valgus in the skeletally immature. J Pediatr Orthop 2014; 34(4): 441-6.

- Hsu L C S, O‘Brien JP, Yau ACMC, et al. Valgus deformity of the ankle in children with fibular pseudoarthrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1974; 56: 503-10.

- Kumar S J, Keret D, MacEwen G D. Corrective cosmetic supramalleolar osteotomy for valgus deformity of the ankle joint: a report of two cases. J Pediatr Orthop 1990; 10: 124-127.

- Langenskiöld A. Pseudoarthrosis of the fibula and progressive valgus deformity of the ankle in children: treatment by fusion of the distal tibial and fibular metaphyses. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1967; 49: 463-70.

- Lubicky J P, Altiok H. Transphyseal osteotomy of the distal tibia for correction of valgus/varus deformities of the ankle. J Pediatr Orthop 2001; 21(1): 80-8.

- Makin M. Tibio-fibular relationship in paralysed limbs. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1965; 47: 500-6.

- Malhotra D, Puri R, Owen R. Valgus deformity of the ankle in children with spina bifida aperta. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1984; 66: 381-5.

- Rupprecht M, Spiro A S, Rueger J M, Stücker R. Temporary screw epiphyseodesis of the distal tibia: a therapeutic option for ankle valgus in patients with hereditary multiple exostosis. J Pediatr Orthop 2011; 31(1): 89-94.

- Rupprecht M, Spiro A S, Schlickewei C, et al. Rebound of ankle valgus deformity in patients with hereditary multiple exostosis. J Pediatr Orthop 2014 Jun 24. [Epub ahead of print]

- Sharrard W J W, Grosfield I. The management of deformity and paralysis of the foot in myelomeningocele. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1968; 50: 456-65.

- Stevens P M, Belle R M. Screw epiphysiodesis for ankle valgus. J Pediatr Orthop 1997;17:9-12.

- Stevens P M, Kennedy J M, Hung M. Guided growth for ankle valgus. J Pediatr Orthop 2011; 31(8): 878-83.

- Thompson T C, Straub L R, Arnold W D. Congenital absence of the fibula. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1957: 39-A: I 229-36.

- Tompkins M, Eberson C, Ehrlich M. Hemiepiphyseal stapling for ankle valgus in multiple hereditary exostoses. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2012; 41(2): 23-6.

- Wiltse L. Valgus deformity of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1972: 54-A: 595-606.