Abstract

Background and purpose — The effects of launch or closure of an entire arthroplasty unit on the first or last patients treated in these units have not been studied. Using a 3-year follow-up, we investigated whether patients who were treated at the launch or closure stage of an arthroplasty unit of a hospital would have a higher risk of reoperation than patients treated in-between at the same units.

Patients and methods — From the Finnish Arthroplasty Register, we identified all the units that had performed total joint arthroplasty and the units that were launched or closed in Finland between 1998 and 2011. The risks of reoperation within 3 years for the 41,748 total hip and knee replacements performed due to osteoarthritis in these units were modeled with Cox proportional-hazards regression, separately for hip and knee and for the launch and the closure stage.

Results — The unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for total hip and knee replacements performed in the initial stage of activity of the units that were launched were similar to the reoperation risks in patients who were operated in these units after the early stage of activity. The unadjusted and risk-adjusted HRs for early reoperation after total hip replacement (THR) were increased at the closure stage (adjusted HR = 1.8, 95% CI: 1.2–2.8). The reoperation risk at the closure stage after total knee replacement (TKR) was not increased.

Interpretation — The results indicate that closure of units performing total hip replacements poses an increased risk of reoperation. Closures need to be managed carefully to prevent the quality from deteriorating when performing the final arthroplasties.

How good are hospitals at maintaining the quality of a treatment they offer over time? Quality of care may be perceived as a relatively stable characteristic, but at some stage the quality of care could deviate from the hospital’s average. For example, variations in the quality of an activity might appear when a specific treatment is launched or when it is being discontinued in a hospital.

The initiation of total joint replacement surgery in a new setting might entail a learning curve, manifest as an increased risk of early reoperation in the initial stage of the unit’s functioning. To initiate replacement surgery in a hospital, the team members must be recruited and the team may have a learning curve (Reagans et al. Citation2005). It would presumably take time for the team to reach full efficiency. In the event that a hospital decides to close a unit performing replacement surgery, members of the surgical team might lose their motivation or seek other employment opportunities, thus leading to a high turnover of the members of the surgical team. As a consequence of this, the quality of care might be affected (Cavanagh 1998, Cummings and Estabrooks Citation2003, Misra-Hebert et al. Citation2004, Buchan Citation2010).

We investigated whether patients who underwent total joint replacement in the launch or closure phase between 1998 and 2011 had a higher risk of reoperation within 3 years than patients who were operated on in the same units after the launch phase or before the closure phase. In addition, we studied the performance of all the units that carried out total joint replacements in Finland, and evaluated the performance of the units that opened or closed in relation to units with continuous total joint replacement surgery over the period 1998–2011.

Patients and methods

Data

We gathered individual-level administrative data on all total hip and knee replacements performed in Finland between 1996 and 2013 from several registers. The Finnish Arthroplasty Register (FAR) was used to identify all total hip and knee replacements, and the patients’ hospital discharge records from the beginning of 1987 to the end of 2013 were extracted from the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register (FHDR). The FAR and FHDR covered all units, both public and private, that performed total joint replacements in the study period. In addition, data on the patients’ purchases of prescribed medications and special reimbursement decisions were gathered from the administrative databases of the Social Insurance Institution (SII) for the period 1998–2013.

The individual-level data on operations, which were used in analysis of the risk of reoperation in the 3 years after the primary surgery, only included operations performed due to osteoarthritis in the period 1998–2011. We also used the individual-level data collected for the Performance, Effectiveness, and Costs of Treatment Episodes (PERFECT) project (Häkkinen Citation2011, Mäkelä et al. Citation2011). According to the PERFECT study protocol, patients who had previously presented with symptoms indicating possible mechanisms other than primary osteoarthritis as the cause of surgery were excluded (diagnoses are listed in Mäkelä et al. Citation2011). Patients who were not Finnish citizens or who were residents of the Åland Islands were also excluded from the individual-level study data, since their use of the hospital service could not be tracked reliably using the Finnish registries.

Reoperations—including revisions of the joint, implant removals, and (in knee cases) the addition of a patellar part—were tracked using both the FAR and the FHDR until December 31, 2013. From the FHDR, the codes NFC* and NGC* of the Finnish version of the NOMESCO classification of surgical procedures (meaning secondary prosthetic replacement of the hip and knee joint) were used to identify the reoperations. Patients suffering from heart failure (WHO International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition (ICD-10) codes I50*), coronary heart disease (I20* to I25*), atrial fibrillation (I48*), hypertension (I10* to I15*, diabetes (E10* to E14*), psychotic disorders (F20* to F31*), cancer (C00* to C99*), or depression (F32* to F34*) were identified based on diagnoses in the hospital discharge records and the special reimbursements for medications for these diseases issued by the SII prior to surgery. For a more detailed description of the registry methodology used, see Peltola et al. (Citation2011). For an analysis of the effects of the selected comorbid conditions on reoperation risk, see Jämsen et al. (Citation2013).

Definitions of launched and closed units, and the stage of surgery

For each unit performing arthroplasty in Finland, we calculated the number of total hip and knee replacements the units had performed each year between 1997 and 2012, using the FAR. We considered a unit that performed total hip or knee replacements in any year between 1998 and 2011, but that had not performed these surgeries in the previous year, to be a unit that had newly opened. Likewise, a unit that did not perform total hip or knee replacement in the year after any of the years 1998–2011 was considered to have been discontinued.

For the launched and closed units that performed at least 200 total joint replacements between 1998 and 2011, we analyzed reoperation risk within 3 years of the primary surgery (using the individual-level data), which is referred to from here on as risk of early reoperation. For the units that were launched or closed, the total hip and knee replacements performed for any reason were assigned order numbers within each unit, based on the date of surgery.

In the units that were launched, the early (or launch) stage was taken to cover the first 100 total hip or knee replacements of the unit. Similarly, the closure stage in the units that were closed was taken to cover the last 100 surgeries in the unit. Our choice of the first or last 100 surgeries was arbitrary, but as the numbers of units that had been launched or closed were presumably low, the data would not permit the use of a continuous—or more finely classified—launch or closure stage.

For all surgeries in the units that were launched, we compared the risk of early reoperation in patients who were operated on in the early stage of the unit’s functioning with that for surgeries performed in these units after the early stage of functioning. In the individual-level analyses of the units that were closed, the risk of early reoperation of the surgeries performed at the closure stage was compared with that for surgeries performed prior to the closure stage.

Statistics

The total joint replacements performed in the launching and closing units were described by giving frequencies or mean values for patient and operation characteristics. We graphically displayed the risk-adjusted reoperation rates with 95% confidence intervals for all units with more than 100 total hip or knee replacements in the study period, using the individual-level study data and separately for hip and knee replacements. The 3-year reoperation rates in the hospitals were based on the observed number of reoperations in 3 years, divided by the expected number of reoperations provided by logistic regression analysis for each unit, with the rate of 1.0 as the average reoperation rate in all units. The factors used in the risk adjustment were sex, age (classified as below 65, 65–69, 70–74, and 75 and over), fixation method (cemented, uncemented, or hybrid), year of surgery, and the comorbid diseases mentioned previously.

We calculated Kaplan-Meier survival curves for total hip and knee replacement patients who were operated on in the launching and closing units that had at least 200 TJRs between 1998 and 2011, separately for hip and knee replacements, with grouping according to the stage of functioning of the unit in which the surgery was performed. We performed Cox proportional-hazards regression modeling to study the association between launch and closure on the one hand and reoperation risk on the other in the 3 years after the primary replacement. The modeling was done separately for hip and knee replacements. The adjusted models included the same confounders as the logistic regression models used in the risk adjustment of hospital-specific reoperation rates described above. Schoenfeld residuals were used to test that the proportional-hazards assumption was not violated in any model. In addition, as the data might include many observations from the same individual, we performed sensitivity analyses including only the first observed operations of the patients. Only the results that were based on the whole data are shown, as the sensitivity analyses gave similar results.

Results

Altogether, 83 units reported total hip and knee replacements to the FAR in the period 1998–2011. Between 1998 and 2011, 19 units started total joint replacement in Finland, and 8 of these performed more than 200 surgeries in the period. Performance of total hip and knee replacements was discontinued in 30 units, and 20 of these had performed more than 200 total hip and knee replacements since 1998 before closing.

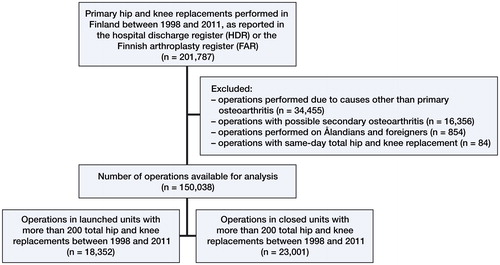

According to the FAR and the FHDR, 201,787 total hip and knee replacements were performed in Finland in the years 1998–2011 (). After exclusions, 150,038 total hip and knee replacements were included in the individual-level study data. Of these surgeries, 7,678 were total hip replacements (THRs) and 10,674 were total knee replacements (TKRs) performed in the units that had launched surgery (). 10,650 THRs and 12,746 TKRs were included in the analysis of the reoperation risk at the closure stage in the units that had closed.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of total hip and knee replacements in launched and closed arthroplasty units in Finland between 1998 and 2011

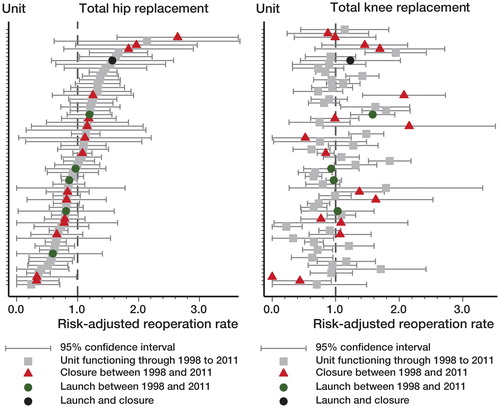

The risk-adjusted 3-year reoperation rates showed that units (with at least 100 surgeries at the individual-level data) varied in their reoperation rates, for both THR and TKR (). For THR, the performance of the units that were launched was better than average—or was average—compared to all the units. For TKR, one launched unit had a poorer performance than the units had on average. In both hip and knee replacement, the performance of the closed units was distributed evenly across the whole spectrum of performance. also shows that a unit’s risk-adjusted reoperation rate in THR was not on a par with its performance in TKR.

Figure 2. Risk-adjusted reoperation rate for reoperation within 3 years, with 95% CI, for units that performed total joint replacements in Finland between 1998 and 2011. Total hip and knee replacements are shown separately, ordered by risk-adjusted rate of hip replacements.

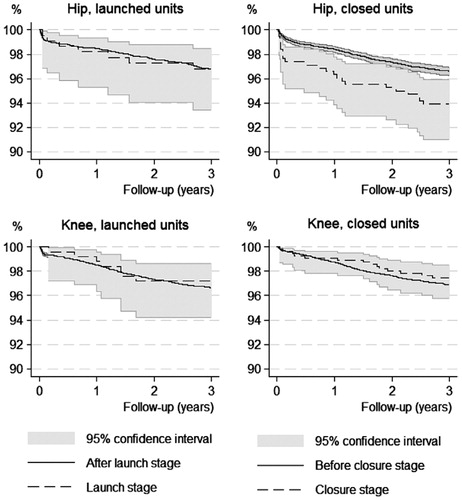

In the newly started units, THRs and TKRs performed at the early stage of functioning did not have different implant survivorship from corresponding surgeries performed after the early stage of functioning in the same units. In the units that were closed, the THRs performed at the closure stage had statistically significantly worse implant survivorship than THRs performed prior to the closure stage (p = 0.004, log-rank test). In TKR, implant survivorship was similar before the closure stage and at the closure stage ().

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for hip and knee replacements in launched and closed units (with at least 200 TJRs between 1998 and 2011).

The unadjusted and risk-adjusted hazard ratios for THRs and TKRs performed at the early stage of functioning in the newly opened units was different from the reoperation risk in patients who were operated on in the newly opened units after the early stage (). The unadjusted and risk-adjusted hazard ratios for early reoperation after THR were statistically significantly higher at the closure stage (), but there was no increase in reoperation risk at the closure stage after TKR.

Table 2. Unadjusted and risk-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs; with 95% CI) for early revision in the launch stage of units that were opened

Table 3. Unadjusted and risk-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs; with 95% CI) for early revision in the closure stage of units that were closed

Discussion

Teamwork is an essential component in providing good-quality care (see, for example, Manser Citation2009, Bosch et al. Citation2009, Weaver et al. Citation2010, Leonard and Frankel Citation2011). The launch stage involves education and learning-by-doing in the operating team. In orthopedics, operating room teamwork plays a central role in maintaining efficiency, quality of care, and meeting of operating room standards, with deficiencies in communication being a major factor behind, for example, most wrong-site surgeries (Wong et al. Citation2009, Kellett et al. Citation2012, Van Strien et al. Citation2011). Hospital closures have gained attention in the literature, and the consequences of closures have been investigated from the points of view of nurses, physicians, and patients—and also from the standpoint of neighboring hospitals (Dombrosk and Tracy Citation1978, Havlovic et al. Citation1998, Brownell et al. Citation1999, Shanahan et al. Citation1999, Hemmelgarn et al. Citation2001, Liu et al. Citation2001, Cummings and Estabrooks Citation2003). However, the effects of closure on the last patients treated in the units that are to be closed have not been studied.

Of all the units that performed more than 200 total joint replacements between 1998 and 2011, 8 units started and 20 units ended total joint replacement surgery in Finland. The performance of these units, as measured by the risk-adjusted reoperation rate by the end of 2013, appeared to be distributed evenly across the spectrum of performance of all units that had performed total joint replacement over the study period. Our results showed that launch of total joint replacement was not associated with an increased risk of early reoperation for the first 100 patients who were operated on in these units (i.e. during the launch stage) when compared to surgeries after the launch stage. However, the last 100 THRs performed at the closure stage had an increased risk of reoperation compared to THRs in these units before the closure stage. In TKR, such an effect before closure was not found. The reason for an increased risk of reoperation after hip replacement might be luxations, but our data do not allow us to verify this idea.

Our study showed that registry or administrative data can be used in the analysis of the effects of restructuring of hospital services, or of a treatment such as total joint replacement, on the outcomes of treatment. The results suggest that hospital closures should be carefully managed in order to avoid deterioration of the quality of care and patient safety. We believe that the external validity of our results is good, since the effects are mediated through factors related to teamwork and motivation, which are universal phenomena.

The present study had a number of limitations. Most importantly, we did not have data on operating room personnel and personnel turnover at the different stages of operation of a unit. In the data, it was not possible to identify the surgeons, so we were unable to distinguish between experienced and inexperienced surgeons. In Finland, surgeons may operate at several hospitals, and this may have confounded the results. Usually, however, the surgeons who move between hospitals are experienced professionals. If such a surgeon had performed surgery in 1 or more of the units that were to close, when the resident surgeons were not available, this could have had an effect on our results. The possible bias stemming from this could lead to an underestimate of the reoperation risk at the closure stage. Similarly, in the units that started up, the surgeons performing the replacements were more likely to be experienced orthopedists, thus affecting reoperation risk estimates in the launched units.

The low number of patients operated on in the units that were launched or closed did not allow a more detailed specification of the learning effect. For instance, it has been shown that introduction of a new hip or knee implant in a hospital entails a learning effect for the first 15 operations only (Peltola et al. Citation2012,Citation2013), and the implementation of a new technique such as hip resurfacing entails a learning curve of around 25 operations (Nunley et al. Citation2010)—or for anterior-supine minimally invasive THA, of around 40 operations (Seng et al. Citation2009). Thus, the 100-patient limit in our study may not have been sufficiently sensitive to effects that would be reflected by only the very first patients who were operated on in the units. In addition, as we did not have information on the dates that closures were announced to the personnel in the units that were to close, we were not able to use calendar time to identify the surgeries performed in the actual closure stage. The coverage, accuracy, and reliability of the Finnish administrative health data used in the study have been shown to be adequate (Jämsen et al. Citation2009, Sund Citation2012).

The incidences of THR and TKR have increased (Pabinger and Geissler Citation2014, Pabinger et al. Citation2015), and to meet this increasing demand new units performing total hip and knee replacement may be established. On the other hand, in a public healthcare system with financial pressure to reorganize the supply of services, centralization of surgery and closure of units is a likely scenario. Decision makers need information on the details of the supply of services and on the consequences that reorganization services may have on the quality of care for the patients. Our study improves our understanding of the dynamic features of surgical teamwork and their effect on quality. The data do not allow us to make strong inferences on whether the differences in outcomes between hospitals are primarily related to the characteristics of the patients or to the performance of the centers. The differences in reoperation rates indicate a need for continuous benchmarking of centers undertaking hip and knee arthroplasty, and auditing of those with poor results.

The outcome of total joint replacement is not independent of changes in the production environment. In particular, before closing a unit, decision makers should pay attention to the quality of the healthcare given. Our findings highlight the fact that closures should be managed carefully to prevent the quality from deteriorating when performing the last arthroplasties in a unit.

MPe conceived the study, prepared and analyzed the data, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. AM, MPa, and SS took part in designing the study, interpreting the results, and editing the manuscript.

The study was supported by funding from Orton Hospital, Helsinki.

No competing interests declared.

- Bosch M, Faber M J, Cruijsberg J, Voerman G E, Leatherman S, Grol R P T M, Hulscher M, Wensing M. Effectiveness of patient care teams and the role of clinical expertise and coordination: a literature review. Med Care Res Rev 2009; 66 (6 suppl): 5S-35S.

- Brownell M D, Roos N P, Burchill C. Monitoring the impact of hospital downsizing on access to care and quality of care. Med Care 1999; 37 (6 Suppl): JS135-50.

- Buchan J. Reviewing the benefits of health workforce stability. Hum Resour Health 2010; 8: 29.

- Cavanagh S J. Nursing turnover: literature review and methodological critique. J Adv Nurs 1989; 14 (7): 587-596.

- Cummings G, Estabrooks C A. The effects of hospital restrucvturing that included layoffs on individual nurses who remained employed: a systematic review of impact. Int J Soc & Social Policy 2003; 23 (8/9): 8-53.

- Dombrosk S, Tracy R M. Impact of hospital closures on nearby hospitals studied. Hospitals 1978; 52 (23): 82-5, 129.

- Havlovic S J, Bouthillette F, van der Wal R. Coping with downsizing and job loss: lessons from the Shaughnessy Hospital closure. Can J Adm Sci Rev Canad Sci Admin 1998; 15 (4): 322-332.

- Hemmelgarn B R, Ghali W A, Quan H. A case study of hospital closure and centralization of coronary revascularization procedures. CMAJ 2001; 164 (10): 1431-1435.

- Häkkinen U. The PERFECT project: measuring performance of health care episodes. Ann Med 2011; 43 (1 Suppl): S1-S3.

- Jämsen E, Huotari K, Huhtala H, Nevalainen J, Konttinen Y T. Low rate of infected knee replacements in a nationwide series–is it an underestimate? Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (2): 205-212.

- Jämsen E, Peltola M, Eskelinen A, Lehto M U. Comorbid diseases as predictors of survival of primary total hip and knee replacements: a nationwide register-based study of 96 754 operations on patients with primary osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72 (12): 1975-1982.

- Kellett C F, Mackay N D, Smith J M. The WHO checklist is vital, but staff operating room etiquette skills may be as important in reducing errors in arthroplasty theatre. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; 94-B (SUPP XXXVIII): 123.

- Leonard M W, Frankel A S. Role of effective teamwork and communication in delivering safe, high-quality care. Mt Sinai J Med 2011; 78 (6): 820-826.

- Liu L, Hader J, Brossart B, White R, Lewis S. Impact of rural hospital closures in Saskatchewan, Canada. Soc Sci Med 2001; 52 (12): 1793-1804.

- Manser T. Teamwork and patient safety in dynamic domains of healthcare: a review of the literature. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2009; 53 (2): 143-151.

- Misra-Hebert A D, Kay R, Stoller J K. A Review of physician turnover: rates, causes, and consequences. Am J Med Qual 2004; 19 (2): 56-66.

- Mäkelä K T, Peltola M, Sund R, Malmivaara A, Häkkinen U, Remes V. Regional and hospital variance in performance of total hip and knee replacements: a national population-based study. Ann Med 2011; 43 (1 Suppl): S31-S38.

- Nunley R M, Zhu J, Brooks P J, Engh C A Jr, Raterman S J, Rogerson J S, Barrack R L. The learning curve for adopting hip resurfacing among hip specialists. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468 (2): 382-91.

- Pabinger C, Geissler A. Utilization rates of hip arthroplasty in OECD countries. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014; 22 (6): 734-741.

- Pabinger C, Lothaller H, Geissler A. Utilization rates of knee-arthroplasty in OECD countries. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015 May 29. pii: S1063-4584(15)01165-6. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.05.008. [Epub ahead of print].

- Peltola M, Juntunen M, Häkkinen U, Rosenqvist G, Seppälä T T, Sund R. A methodological approach for register-based evaluation of cost and outcomes in health care. Ann Med 2011; 43 (1 Suppl): S4-S13.

- Peltola M, Malmivaara A, Paavola M. Introducing a knee endoprosthesis model increases risk of early revision surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012; 470 (6): 1711-1717.

- Peltola M, Malmivaara A, Paavola M. Hip prosthesis introduction and early revision risk. A nationwide population-based study covering 39,125 operations. Acta Orthop 2013; 84 (1): 25-31.

- Reagans R, Argote L, Brooks D. Individual experience and experience working together: predicting learning rates from knowing who knows what and knowing how to work together. Manag Sci 2005; 51 (6): 869-881.

- Seng B E, Berend K R, Ajluni A F, Lombardi Jr A V. Anterior-supine minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty: defining the learning curve. Orthop Clin North Am 2009; 40 (3): 343-350.

- Shanahan M, Brownell M D, Roos N P. The unintended and unexpected impact of downsizing: costly hospitals become more costly. Med Care 1999; 37 (6 Suppl): JS123-34.

- Sund R. Quality of the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register: a systematic review. Scand J Public Health 2012; 40 (6): 505-515.

- Van Strien T, Dankelman J, Bruijn J, Feilzer Q, Rudolphy V, Van Der Linden Van Der Zwaag E, Van Der Heide H, Valstar E, Nelissen R. Efficiency and safety during knee arthroplasty surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93-B (SUPP II): 115.

- Weaver S J, Rosen M A, DiazGranados D, Lazzara E H, Lyons R, Salas E, Knych S A, McKeever M, Adler L, Barker M, King H. Does teamwork improve performance in the operating room? A multilevel evaluation. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2010; 36 (3): 133-142.

- Wong D A, Herndon J H, Canale S T, Brooks R L, Hunt T R, Epps H R, Fountain S S, Albanese S A, Johanson N A. Medical errors in orthopaedics. Results of an AAOS member survey. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91 (3): 547-557.