Abstract

Background and purpose — Intraoperative periprosthetic femoral fracture is a known complication of cementless total hip arthroplasty (THA). We determined the incidence of—and risk factors for—intraoperative calcar fracture, and assessed its influence on the risk of revision.

Patients and methods — This retrospective analysis included 3,207 cementless THAs (in 2,913 patients). 118 intraoperative calcar fractures were observed in these hips (3.7%). A control group of 118 patients/hips without calcar fractures was randomly selected. The mean follow-up was 4.2 (1.8–8.0) years. Demographic data, surgical data, type of implant, and proximal femur morphology were evaluated to determine risk factors for intraoperative calcar fracture.

Results — The revision rates in the calcar fracture group and the control group were 10% (95% CI: 5.9–17) and 3.4% (CI: 1.3–8.4), respectively. The revision rate directly related to intraoperative calcar fracture was 7.6%. The Hardinge approach and lower age were risk factors for calcar fracture. In the fracture group, 55 of 118 patients (47%) had at least one risk factor, while only 23 of118 patients in the control group (20%) had a risk factor (p = 0.001). Radiological analysis showed that in the calcar fracture group, there were more deviated femoral anatomies and proximal femur bone cortices were thinner.

Interpretation — Intraoperative calcar fracture increased the risk of revision. The Hardinge approach and lower age were risk factors for intraoperative calcar fracture. To avoid intraoperative fractures, special attention should be paid when cementless stems are used with deviant-shaped proximal femurs and with thin cortices.

The use of cementless femoral stems in total hip arthroplasty (THA) has increased in recent years (Mäkelä et al. Citation2010, SHAR Citation2011, THL Citation2011, AOANJRR Citation2012). One reason for this shift has been the associated lower revision rate due to aseptic loosening in young patients (Wechter et al. Citation2013). On the other hand, better survival of THAs with cemented stems than with cementless stems has been found in older patients (Mäkelä et al. Citation2014). A close geometric fit between cementless femoral stems and supporting proximal femoral bone has been proposed to be essential for long-term implant fixation (Soballe et al. 1992, Dorr et al. Citation1993, Fessy et al. Citation1997, Laine et al. Citation2000, Emerson et al. Citation2002, Lecerf et al. Citation2009). Implant designs have been improved and tapered, and porous-coated stems have been introduced (Kim and Kim Citation1993, McLaughlin and Lee Citation1997, McNally et al. Citation2000, Casper et al. Citation2012, Streit et al. Citation2013).

Intraoperative calcar fracture is a known complication of cementless THA (Lindahl Citation2007). Female sex, higher age, smaller stem size, and thin cortical bone have been reported to be risk factors for intraoperative femoral fracture (Napoli et al. Citation2012, Ponzio et al. Citation2015).

We investigated the incidence of and risk factors for intraoperative calcar fracture in cementless THAs. Several radiographic classifications have been proposed to assess the shape and cortical thickness of the proximal femur (Noble et al. Citation1988, Rubin et al. Citation1992, Dorr et al. Citation1993, Husmann et al. Citation1997, Laine et al. Citation2000, Yeung et al. Citation2006, SHAR Citation2011). We used the Noble and Dorr classifications for our radiological analysis of the anatomy of the proximal femur. In addition, we studied whether the femoral component migrated during follow-up, how the fractures were treated, and whether calcar fracture influenced the revision risk.

Patients and methods

Patients

This was a retrospective case-control study. 3,207 THAs (in 2,913 patients, 1,609 males (50%)) underwent cementless THA between January 2004 and December 2009 in 3 participating university hospitals (). The mean follow-up time was 4.2 (1.8–8.0) years.

Table 1. Patient demographics and surgical data

There were 118 intraoperative calcar fractures (3.7%). A control group was formed by selecting THAs from the patient pool of 3,090 THAs without calcar fracture by using a random number generator. The control patients were stratified according to hospital.

THAs were done from the lateral decubitus position via the posterolateral or direct lateral (Hardinge) surgical approach. The operations were performed by 39 orthopedic surgeons and by 7 residents under the direct supervision of the senior orthopedic surgeon.

The THAs used 16 different cementless femoral stems (), which were arbitrarily divided into 3 groups based on design: tapered (e.g. Conserve Profemur TL (Wright Medical Technology, Arlington, TN), M/L Taper (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN), and Corail (DePuy Orthopaedics, Warsaw, IN)); fit and fill (e.g. Bi-Metric (Biomet, Warsaw, IN) and Synergy (Smith and Nephew, Memphis, TN); and other (e.g. Reach (Biomet) and Biomet CDH). THAs were performed according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Treatment of the intraoperative calcar fractures included fixation with cables (n = 114) or partial weight bearing without cables (n = 4). In the control group, full immediate weight bearing was allowed for all patients. Reasons for revision were analyzed from the patient medical records and radiographs.

Risk factors

Patient-dependent risk factors (age, sex, diagnosed osteoporosis, long-term oral cortisone medication for any reason, rheumatoid arthritis, and history of alcohol abuse) were analyzed from the patient medical records (). Other patient-dependent factors such as developmental dysplasia of the hip, previous childhood hip osteotomies, and acute and previous hip fractures were also evaluated and considered as potential risk factors. Diagnosis of hip dysplasia was based on the patient medical records. Surgeon’s experience (consultant orthopedic surgeon or resident) was also analyzed as a risk factor.

Table 2. Risk factors for calcar fracture

Radiological analysis

Radiological analyses were based on preoperative and postoperative radiographs, and also the latest radiograph. The first postoperative radiograph was taken in the supine position during the first 48 h after THA. Subsequent radiographs were taken in the standing position. Picture archiving and communication systems (PACS) were used in every participating hospital, and radiological scaling with a magnifying marker was used for every radiograph.

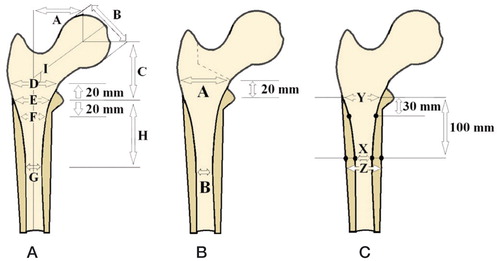

The canal flare index (CFI) was calculated (). The CFI expresses the shape of the proximal femur. CFIs < 3.0 are described as stovepipe-shaped canals, 3.0–4.7 as normal canals, and 4.8–6.5 as champagne flute-shaped canals (Noble et al. Citation1988).

Figure 1. A. Radiological measurements of the proximal femur according to Noble: A, femoral head offset; B, femoral head diameter; C, femoral head position; D, canal width 20 mm above the mid-lesser trochanter line; E, canal width at the mid-lesser trochanter line; F, canal width 20 mm below the mid-lesser trochanter line; G, isthmus diameter; H, isthmus position below the mid-lesser trochanter line; I, neck-shaft angle. B. Radiological canal flare index (CFI) measurements of the proximal femur according to Noble: A, canal width +20 mm above the mid-lesser trochanter line; B, isthmus diameter. CFI = A / B. C. Radiological measurements of the proximal femur: canal-calcar ratio (X / Y) and cortical index ((Z − X) / Z).

Femurs were qualitatively assessed based on 3 distinct patterns of the shape and bone structure of the proximal femur (Dorr et al. Citation1993). Type-A femurs had thick medial and lateral cortices on anterior-posterior radiographs and a large posterior cortex on lateral radiographs. Thick diaphyseal cortices render the proximal femur funnel-shaped. Type-B femurs showed bone loss from the medial cortex on anterior-posterior radiographs and from the posterior cortex on lateral radiographs. The intramedullary canal of type-B femurs was wider than that in type-A femurs. Type-C femurs had lost nearly all medial and posterior cortices; they were thin and might display a fuzzy appearance on radiographs. The intramedullary canal diameter was usually wide on lateral radiographs. Anterior-posterior cortical index, mediolateral cortical index, and the canal-to-calcar ratio were measured () (Dorr et al. Citation1993).

Migration of the femoral component during follow-up was evaluated by measuring the distance from the tip of the greater trochanter to the femoral component shoulder, based on postoperative radiographs and the most recently obtained radiograph after calibration of the digital radiographic image measurement tool.

Measurements were re-analyzed after 2 months, by the same observer (SM) to determine intraobserver agreement and by the other observer (JK) to determine interobserver agreement. The reliability of the observers was also evaluated with a parallel test.

Statistics

For continuous variables, comparisons between the calcar fracture group and the control group were done using the Mann-Whitney U-test. For categorical variables, Pearson’s chi-square test was used. Fischer’s exact test was used to analyze differences in operative diagnosis between the groups. The multivariable logistic regression model was used, due to heterogeneity of the variables involved affecting the risk of calcar fracture. The variables selected for analysis are known to be potentially confounding factors for arthroplasty registry database studies. These variables were age, sex, surgical approach, and proximal femur morphology according to Noble and Dorr. The selection of these adjustment variables was based on our own hypotheses and the previous literature. There are many different radiological measurements and classifications of the proximal femur in the literature, but we believe that the Noble and Dorr classifications are the best known and the most often used. Bland-Altman comparison analysis was used to determine the intra- and interobserver agreement, and Pitman’s test of difference was done to study intra- and interobserver reliability. Any p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data were analyzed using SPSS 19.0.0 and Stata 13 software.

Ethics

The ethics review committee of the University of Turku gave permission for this study (ETMK: 78/1801/2013).

Results

The incidence of intraoperative calcar fracture in the 3,207 patients was 3.7%. In the calcar fracture group, the incidence of hip dysplasia was 20%, as compared to 9.3% in the control group (p = 0.001) (). There was no statistically significant difference in follow-up time between the calcar fracture group and the control group.

The multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that the Hardinge approach was an independent risk factor for calcar fracture (OR = 2.4, 95% CI: 1.3–4.4) (). The Hardinge approach was used in 70% of the THAs in the calcar fracture group but in only 47% of the THAs in the control group (p = 0.01) (). The multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that lower age was an independent risk factor for calcar fracture (OR = 0.94, CI: 0.94–1.00; p = 0.03).

There was a statistically significant difference in the distribution of femoral stem types between groups (p = 0.006) (). The mean migration of the femoral component during follow-up was 1.2 (0–23) mm in the calcar fracture group and 0.7 (0–28) mm in the control group (p = 0.2).

Risk factors for calcar fracture

In the calcar fracture group, 55 of the 118 patients (47%) had at least 1 risk factor; in the control group, the corresponding number was 23 of 118 (20%; p = 0.001) ().

Consultant orthopedic surgeons performed 113 of the 118 operations (96%) in the calcar fracture group and 116 of the 118 operations (98%) in the control group. Residents carried out 5 of the 118 THAs (4%) in the calcar fracture group and 2 of the 118 THAs (1.7%) in the control group (p = 0.03).

Influence of calcar fracture on revision surgery

Revision for any reason was performed on 12 of the 118 patients (10%; CI: 5.9–17) in the calcar fracture group and on 4 of the 118 patients (3.4%; CI: 1.3–8.4) in the control group (p = 0.04). In the calcar fracture group, 9 of the 12 revisions were performed as a result of calcar fracture during the index operation. 4 of 9 of these femoral revisions were performed within 2 days after the index surgery. All of these 4 revisions were performed because the intraoperative calcar fracture was not diagnosed until the postoperative radiography. On the other hand, the revision rate after adequate cable fixation during the index surgery was 4% (5/118). There were 8 femoral stem revisions in a subgroup (n = 114) in which the intraoperative calcar fracture was treated with cables and full or partial weight bearing. 4 calcar fractures were treated with partial weight bearing without cables and 1 one of these had a femoral stem revision (p = 0.02).

Morphological measurements from radiographs

In the calcar fracture group, the patients had narrower proximal femoral canals and more varus femoral necks ().

Table 3. Radiological measurements of femoral canal shape according to Noble (Noble et al. Citation1988)

Table 4. Classification of femoral canal shape according to Noble et al. (Citation1988). 118 hips in each group

Table 5. Radiological measurements according to Dorr et al. (Citation1993)

Table 6. Radiological classification according to Dorr et al. (Citation1993). 118 hips in each group

Table 7. Multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted for age and sex. In the Noble classification, stovepipe-type and champagne flute-type proximal femurs were compared to normal-type proximal femurs. In the Dorr classification, Dorr type-B and Dorr type-C were compared to Dorr type-A

The multivariable logistic regression analyses were done by comparing proximal femur types according Noble and Dorr classifications with adjustment for age and sex (Noble et al. Citation1988, Dorr et al. Citation1993). In the Noble classification, stovepipe-type and champagne flute-type proximal femurs were compared to normal-type proximal femurs to evaluate the risk of intraoperative calcar fracture of these 2 types of proximal femurs. The stovepipe-type proximal femurs did not have a higher risk of intraoperative calcar fracture than normal-type proximal femurs (OR = 1.9, CI: 0.76–4.9; p = 0.2) (). The champagne flute type had a higher risk of having intraoperative calcar fracture than the normal type (OR = 2.8, CI: 1.1–6.9) (). In the Dorr classification, Dorr type B and Dorr type C were compared with Dorr type A. Dorr type B did not have a higher risk of intraoperative calcar fracture than Dorr type A (OR = 1.5, CI: 0.76–2.9) (). There was a higher risk of calcar fracture if the proximal femur was Dorr type C rather than Dorr type A (OR = 6.5, CI: 1.3–33) ().

Intra- and interobserver error

The mean difference between intraobserver measurements ranged from −2.3 mm to 1.3 mm (CI: −3.8 to 3.8) and the mean difference in measured neck-shaft angle was −2.3° (CI: −3.8 to −0.8). The mean difference between interobserver measurements ranged from −0.2 mm to 4.0 mm (CI: −1.7 to 5.8) and the mean difference in measured neck-shaft angle was −2.5° (CI: −5.7 to 0.7). Pitman’s test revealed that there were no statistically significant differences in agreement or in the reliability of intraobserver and interobserver measurements.

Discussion

Second-generation cementless THAs were introduced in the late 1980s, and their use became widespread in the late 1990s (McNally et al. Citation2000, Dumpleton and Manley Citation2005, Kim Citation2005). Correct size and positioning of the femoral component is essential for restoration of the function of the hip and for osseointegration and survival of the implant (Rubin et al. Citation1992). A press-fit stem may cause fracturing of the calcar area of the femur during implantation (Berry Citation2002). Contemporary femoral stems usually have a built-in feature of press-fit, i.e. stems are about 1 mm larger than corresponding broaches. Intraoperative fracture of the calcar area is a well-known complication of cementless THA, but the risk factors for fracture are partly unclear (Berry Citation1999, Lindahl Citation2007).

Heterogeneities in study populations, implants, and surgical approaches affect the incidence of intraoperative calcar fracture after cementless THA. We are not aware of any clinical publication with a study group as large as ours, and where the incidence and reasons for the intraoperative calcar fracture were evaluated in detail. There have been some studies with smaller study groups and with more homogeneous populations and femoral components (Ponzio et al. Citation2015). Reported incidences of intraoperative calcar fracture in these studies have varied between 0.4% and 5.4% (Berry Citation1999, Berend and Lombardi Citation2010, Cameron Citation2004, Ponzio et al. Citation2015). The incidence of calcar fracture in our study was 3.7%, which is similar to that in previous studies.

Surgery was performed more often in the calcar fracture group, due to congenital hip dysplasia or hip fracture. There were also less primary OAs in the fracture group than in the control group. The difference in operative diagnosis may also explain the difference in femoral stem types used in the 2 groups; thus, there were more femur stems of “other” type in the calcar fracture group. Compared to consultant orthopedic surgeons, residents were associated with an increased risk of calcar fracture during surgery.

Treatment of an intraoperative calcar fracture is usually done with cable or wire fixation at the level of the lesser trochanter (Berend et al. Citation2004). In the present study, all but 4 intraoperative calcar fractures were treated with cables. The small number of non-cabled patients meant that comparison between the groups was not meaningful.

The multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that the Hardinge approach was an independent risk factor for calcar fracture. During THA perfomed with this approach, the medial gluteal muscle may direct broaches and final implant positions in the medial and anterior directions, introducing stress forces to the medial cortex and predisposing to calcar fracture. Lower age was also found to be an independent risk factor for calcar fracture. The reason for this finding might be that in the calcar fracture group there were more diagnoses other than osteoarthritis, which was the most common operative diagnosis in the control group. In addition, women have been shown to have a higher risk of calcar fracture with cementless stems (Cameron Citation2004, Ponzio et al. Citation2015). There were more calcar fractures in women, although the difference was not statistically significant. A previous study showed that one reason for the higher calcar fracture rates in women might be related to the smaller dimensions of the proximal femur (Bonnin et al. Citation2015). Our study supports this finding, as we found that deviant proximal femurs (champagne flute and stovepipe types) and thin cortices (Dorr type C) may increase the risk of intraoperative calcar fracture.

The geometry of the proximal femur is critical for press-fitting to the femoral stem and subsequent survival of the THA (Rubin et al. Citation1992). The anatomy and morphology of the proximal femur have been studied repeatedly (Rubin et al. Citation1992, Dorr et al. Citation1993, Laine et al. Citation2000, Casper et al. Citation2012). There are wide variations in the shape of the proximal femur (Noble et al. Citation1988). Aging usually narrows the cortices and simultaneously widens the intramedullary canal of the proximal femur (Newell Citation1997, Casper et al. Citation2012). These changes in bone morphology reduce the strength of the proximal femur and the risk of fracture increases (Casper et al. Citation2012). These changes in bone morphology occur earlier in women than in men (Newell Citation1997, Casper et al. Citation2012). The loss of cortical bone has been reported to occur especially in the lateral cortices, which are responsible for supporting secondary tensile forces (Casper et al. Citation2012). Comparison of middle-aged patients with elderly patients has revealed a decrease in the thickness of cortices in the elderly, which leads to increased isthmus width and decreasing CFI (Casper et al. Citation2012). Our CFIs are comparable to those reported from other studies in which the mean patient age was the same as in our study group (Kavanagh et al. Citation1989, Søballe et al. Citation1992, SHAR Citation2011, Casper et al. Citation2012).

We observed more champagne flute-shaped and stovepipe-shaped proximal femurs in the calcar fracture group than in the control group. There were also more Dorr type-C proximal femurs in the calcar fracture group. This wider type variation in proximal femurs in the calcar fracture group may be because there were more women in the fracture group; women have smaller proximal femurs and smaller CFIs than men. Dysplasia also changes proximal femur anatomy, and the incidence of hip dysplasia was higher in the calcar fracture group.

Our study had some limitations. First, Noble’s CFI is based on isthmus position, and there is user-dependent bias in determination of the canal boundary. This bias was eliminated by selecting corrected points along the boundary. In addition, all measurements were performed by the same investigator. Retrospectively obtained data did not allow us to determine whether X-ray templates or digital templating were used, and whether the size of the implanted stem was different from that of the templated one. Secondly, our study did not reveal whether there was a between-group difference in patient satisfaction with THA.

In conclusion, patients with deviant proximal femurs and wide proximal femur canals with thin cortices were at higher risk of calcar fracture. Patients with indications for surgery other than primary osteoarthritis had a higher risk of intraoperative calcar fracture. The Hardinge approach was associated with a substantially higher risk of intraoperative calcar fracture than the posterior approach. Lower age was also associated with a higher risk of intraoperative calcar fracture, presumably due to increased prevalence of secondary osteoarthritis in the calcar fracture group, as these conditions usually lead to THA in younger patients than primary osteoarthritis does. Our results demonstrate the necessity of considering the various shapes of the proximal femur when selecting cementless femoral stems.

SM participated in planning the study protocol, collecting data, analyzing radiographs, performing statistical analyses, and preparing the manuscript. TM, IK, KM, JK, and VR participated in planning the study protocol, collecting data, and preparing the manuscript. JK also participated by doing the interobserver measurements from the radiographs. HH participated in planning the study protocol, performing statistical analyses, and preparing the manuscript.

This study was made possible by support from the Finnish Arthroplasty Society, the Finnish Research Foundation for Orthopaedics and Traumatology, the Research Foundation of Kuopio University Hospital, the Finnish Cultural Foundation, and the Finnish Medical Foundation Duodecim.

No competing interests declared.

- AOANJRR (Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry) 2012. Publication date: January 2013. Available from http://https://aoanjrr.dmac.adelaide.edu.au/documents/10180/60142/Annual%20Report%202012?version=1.3&t=1361226543157 (last accessed February 01, 2014)

- Berend K R, Lombardi Jr A V. Intraoperative femur fracture is associated with stem and instrument design in primary total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468: 2377–81.

- Berend K R, Lombardi Jr A V, Mallory T H, Chonko D J, Dodds K L, Adams J B. Cerclage wires or cables for the management of intraoperative fracture associated with a cementless, tapered femoral prosthesis: results at 2 to 16 years. J Arthroplasty 2004; 19: 17–21.

- Berry D J. Epidemiology hip and knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999; 30: 183-9.

- Berry D J. Management of periprosthetic fractures: the hip. J Arthroplasty 2002; 17: 11–13.

- Bonnin M P, Neto CC, Aitsiselmi T, Murphy C G, Bossard N, Roche S. Increased incidence of femoral fractures in small femurs and women undergoing uncemented total hip arthroplasty - why? Bone Joint J 2015; 97-B: 741-8.

- Casper D S, Kim G K, Parvizi J, Freeman T A. Morpholofy of the proximal femur differs widely with age and sex. Relevance to design and selection of femoral prostheses. J Orthop Relat Res 2012; 30: 1162-6.

- Cameron H U. Intraoperative hip fractures. J Arthroplasty 2004; 19: 99-103.

- Dumpleton J H, Manley M T. Metal-on-metal total hip replacement. J Arthroplasty 2005; 20: 174-88.

- Dorr L D, Faugere M-C, Mackel A M, Gruen T A, Bognar B, Malluche H H. Structural and cellular assessment of bone quality of proximal femur. Bone 1993; 14: 231-42.

- Emerson Jr R H, Head W C, Emerson C B, Rosenfeldt W, Higgins L L. A comparison of cemented and cementless titanium femoral components used for primary total hip arthroplasty: a radiographic and survivorship study. J Arthroplasty 2002; 17: 584-91.

- Fessy M H, Seutin B, Béjui J. Anatomical basis for the choice of the femoral implant in the total hip arthroplasty. Surg Radiol Anat 1997; 19: 283-6.

- Husmann O, Rubin P J, Leyvraz P F, de Roguin B, Argenson J N. Three-dimensional morphology of the proximal femur. J Arthroplasty 1997; 12: 444-50.

- Kavanagh B F, Dewitz M A, Ilstrup D M, Stauffer R N, Coventry M B. Charnley total hip arthroplasty with cement: Fifteen- year results. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1989; 71: 1496-503.

- Kim Y-H. Long-term results of the cementless porouscoated anatomic total hip prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005; 87: 623-7.

- Kim Y-H, Kim V E M. Uncemented porous-coated anatomic total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1993; 75: 6-14.

- Laine H J, Lehto M U, Moilanen T. Diversity of proximal femoral medullary canal. J Arthroplasty 2000; 15: 86-92.

- Lecerf G, Fessy M H, Philippot R, et al. Femoral offset: anatomical concept, definition, assessment, implications for preoperative templating and hip arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2009; 95: 210-9.

- Lindahl H. Epidemiology of periprosthetic femur fracture around a total hip arthroplasty. Injury 2007; 38: 651-4.

- McLaughlin J R, Lee K R. Total hip arthroplasty with an uncemented femoral component. Excellent result at ten-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1997; 79: 900-7.

- McNally S A, Shepperd J A, Mann C V, Walczak J P. The results at nine to twelve years of the use of a hydroxyapatite- coated femoral stem. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000; 82: 378-82.

- Mäkelä KT, Eskelinen A, Paavolainen P, Pulkkinen P, Remes V. Cementless total hip arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis in patients aged 55 years and older. Results of the 8 most common cementless designs compared to cemented reference implants in the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2010; 81: 42-52.

- Mäkelä K T, Matilainen M, Pulkkinen P, Fenstad A M, Havelin L, Engesaeter L, Furnes O, Pedersen A B, Overgaarg S, Kärrholm J, Malchau H, Garellick G, Ranstam J, Eskelinen A. Failure rate of cemented and uncemented total hip replacements: register study of compined Nordic database of four nations. BMJ 2014; 348: f7592.

- Napoli N, Jin J, Peters K, Wustrack R, Burch S, Chau S, Cauley J, Ensrud K, Kelly M, Black D M. Are women with thicker cortices in the femoral shaft at higher risk of subtrochanteric/diaphyseal fractures? The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 7: 2414-22.

- Newell R L M. The calcar femorale: a tale of historical neglect. Clin Anatomy 1997; 10: 27-30.

- Noble P C, Alexander J W, Lindahl J L, Yew D T, Granberry W M, Tullos H S. The anatomic basis of femoral component design. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988; (235); 148-66.

- Ponzio D Y, Shahi A, Park A G, Purtill J J. Intraoperative proximal femoral fracture in primary cementless total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30: 1418-22.

- Rubin P J, Leyvrax P F, Aubaniac J M, Argenson J N, de Roquin B. The Morphology of the proximal femur. A three-dimensional radiographic analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1992; 74: 28-32.

- SHAR (Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register) 2011. Publication date: October 2012, Available from http://www.shpr.se. (last accessed September 09, 2014)

- Søballe K, Hansen E S, B-Rasmussen H, Jorgensen P H, Bünger C. Tissue ingrowth into titanium and hydroxyapatite-coated implants during stable and unstable mechanical conditions. J Orthop Res 1992; 10: 285-99.

- Streit M R, Innmann M M, Merle C, Bruckner T, Aldinger P R, Gotterbarm T. Long-term (20- to 25-year) results of an uncemented tapered titanium femoral component and factors affecting survivorship. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471: 3262-9.

- THL (The National Institute for Health and Welfare). Lonkka- ja polviproteesit Suomessa 2010. Tilastoraportti 23/2011. Publication date: 22.03.2013. Available from http://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/104402/Tr09_13.pdf?sequence=1 (last accessed October 10, 2014)

- Wechter J, Comfort T K, Tatman P, Mehle S, Gioe T J. Improved survival of uncemented versus cemented femoral stems in patients aged < 70 years in a community total joint registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471: 3588-95.

- Yeung Y Y, Chiu K Y, Yau W P, Tang W M, Cheung W Y, Ng T P. Assessment of the proximal femoral morphology using plain radiograph - can it predict the bone quality? J Arthroplasty 2006; 21: 508-13.