Abstract

Background and purpose — Hip fracture patients usually have low body mass index (BMI), and suffer further postoperative catabolism. How BMI relates to outcome in relatively healthy hip fracture patients is not well investigated. We investigated the association between BMI, survival, and independent living 1 year postoperatively.

Patients and methods — This prospective multicenter study involved 843 patients with a hip fracture (mean age 82 (SD 7) years, 73% women), without severe cognitive impairment and living independently before admission. We investigated the relationship between BMI and both 1-year mortality and ability to return to independent living.

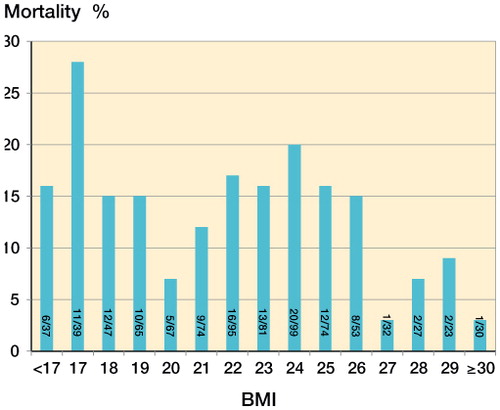

Results — Patients with BMI > 26 had a lower mortality rate than those with BMI < 22 and those with BMI 22–26 (6%, 16%, and 18% respectively; p = 0.006). The odds ratio (OR) for 1-year survival in the group with BMI > 26 was 2.6 (95% CI: 1.2–5.5) after adjustment for age, sex, and physical status. Patients with BMI > 26 were also more likely to return to independent living after the hip fracture (OR = 2.6, 95% CI: 1.4–5.0). Patients with BMI < 22 had similar mortality and a similar likelihood of independent living to those with BMI 22–26.

Interpretation — In this selected group of patients with hip fracture, the overweight and obese patients (BMI > 26) had a higher survival rate at 1 year, and returned to independent living to a higher degree than those of normal (healthy) weight. The obesity paradox and the recommendations for optimal BMI need further consideration in patients with hip fracture.

Up to half of all patients suffering from hip fracture are malnourished upon admission to hospital (Ponzer et al. Citation1999, Bachrach-Lindstrom et al. Citation2000, Fiatarone Singh et al. Citation2009). The trauma and subsequent surgery leads to increased metabolic demands, and a further decline in body weight during the first year postoperatively has been shown (Hedstrom et al. Citation1999). It has also been reported that older individuals have difficulties in increasing protein and energy intake to match the needs that follow major surgery (Sullivan et al. Citation1999, Hebuterne et al. Citation2001). There is no general agreement about the best nutritional marker to use in the postoperative and rehabilitation phase after the fracture. However, body mass index (BMI) is still the most common anthropometric assessment of nutritional status in the elderly as an indicator of malnutrition or obesity, even though it has its limitations in terms of body composition. A recent study on surgical patients in an intensive care unit found an association between increased in-hospital mortality rate and low BMI (< 18.5); in contrast, overweight and obesity was associated with a lower mortality rate (Hutagalung et al. Citation2011). The optimal BMI in old patients with a hip fracture who are known to be in a postoperative catabolic situation (Hedstrom et al. Citation2006) has not been sufficiently investigated. We therefore investigated the association between BMI and 1-year survival in relatively healthy elderly hip fracture patients. A secondary aim was to study the association between BMI and the ability to regain independent living conditions.

Patients and methods

Patients with a hip fracture who were admitted to 4 university hospitals in Stockholm (Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge; Karolinska University Hospital, Solna; Danderyd Hospital; and Stockholm South Hospital) were included consecutively over a 1-year period. Inclusion criteria were age > 65 years, living independently, and no diagnosis of dementia or severe cognitive impairment based on the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ, ≥ 3 correct answers) (Pfeiffer Citation1975). SPMSQ is a 10-item test that is used to detect the presence of cognitive dysfunction. It has been validated with similar rates of sensitivity and specificity to that of the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), which is the most widely used screening test for the assessment of cognitive dysfunction (Haglund and Schuckit Citation1976). In comparison to the MMSE, the SPMSQ is easy to give to bedridden patients, since it does not include writing exercises. In this particular study, patients with severe cognitive impairment and those admitted from nursing homes were excluded.

We classified hip fractures as: (1) fracture of the femoral neck (ICD 10; S72.0), undisplaced (Garden I–II) or displaced (Garden III–IV), (2) trochanteric fractures (Jensen-Michaelsen, ICD 10; S72.1), or (3) sub-trochanteric fractures (ICD 10; S72.2). Undisplaced fractures of the femoral neck were generally fixed internally with 2 cannulated screws. The treatment for displaced fractures of the femoral neck was a total hip replacement or hemiarthroplasty for patients > 70 years of age. Trochanteric and sub-trochanteric fractures were fixed internally with a sliding hip screw or an intramedullary nail. Each patient’s physical status was assessed before surgery by the attending anesthesiologist according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification. The number of medical diagnoses were recorded and included: cardiovascular disease, stroke, respiratory disease, renal disease, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and Parkinson’s disease. Cognitive function was assessed using the SPMSQ (Pfeiffer Citation1975). Living conditions both before the hip fracture and 1 year postoperatively were recorded. Independent living was defined as living in an apartment or house, or in a block of service flats. Living conditions that were not defined as independent were nursing home, long-term medical care, rehabilitation center, or other institutional care. Living alone was defined as not having shared housing with a spouse, relative, or friend. The Katz Index of Activities of Daily Living (ADL) was used to assess patients’ requirements for help in everyday life (Katz et al. Citation1963).

Patients were divided into 3 groups depending on the need for walking aids. Weight was measured on a bed scale upon admission, or postoperatively on a wheelchair scale. Height was measured in supine position. We investigated how different BMI related to 1-year survival. According to the results (see below), the patients were categorized into 3 BMI groups: BMI < 22, 22–26, and > 26. A BMI value of 22 was used as a cutoff for underweight and risk of malnutrition, as suggested by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. The upper limit of 26 was chosen after the investigation of how different BMI levels related to 1-year survival, and also since previous Swedish cohort studies have shown an average BMI of about 26 in community-dwelling men and women aged ≥ 70 years in Sweden (Dey et al. Citation1999, Eiben et al. Citation2005). Mortality during the first year after the fracture was determined from the hospital discharge register and the Swedish population records.

Statistics

Differences between groups regarding age were tested with 1-way ANOVA, and this included multiple comparisons between the 3 BMI groups. Contingency tables with the chi-square test were used in the analysis of differences between the 3 BMI groups, and they were also used to identify possible confounders. The associations between the 3 BMI groups and 1-year survival were evaluated using binary logistic regression analysis to calculate odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), both unadjusted and adjusted for age, sex, and ASA score. The association between the BMI groups and ability to live independently after the hip fracture were similarly analyzed and adjusted for age, sex, ASA score, and having shared housing upon admission. Any p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. We used IBM SPSS statistics version 22 for Windows.

Ethics

The study was performed according to the Helsinki Declaration and the protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (entry no. 206-02). All the patients included gave their formal consent. They could choose to withdraw at any time, and integrity was maintained through an anonymous ID number in the data analysis.

Results ()

2,213 patients were admitted for hip fracture over one year. 843 patients with a mean age of 82 (SD 7) years were eligible for the study; 73% were women. The mean BMI of the patients included was 22.7 (SD 3.8). The characteristics of the 3 BMI groups showed statistically significant differences only for age and sex. The proportion of women was higher, and the patients were older in the group with BMI < 22 compared to the 2 other groups, but the age difference was not significant between those with BMI 22–26 and those with BMI > 26 (). The 1-year mortality rate was 16% in patients with BMI < 22 and it was 18% in those with BMI 22–26. The corresponding figure for those with BMI > 26 was 6%. The unadjusted OR for 1-year survival in patients with BMI > 26 was 2.7 (95% CI: 1.3–5.6) compared to the group with BMI < 22 and it was 3.1 (95% CI: 1.5–6.5) compared to the group with BMI 22–26. During the first year, 128 of the 843 patients died (15%). There was a higher mortality rate in men than in women (19% and 14%; p = 0.06). BMI was independently associated with 1-year survival after adjustment for age, sex, and ASA score ().

Table 1. Patient characteristics according to the 3 BMI groups

Table 2. The association between BMI and 1-year survival, adjusted for ASA, age, and sex using multivariate logistic regression analysis

Figure 1. 1-year mortality in different BMI groups. The number of patients who died (of the total number in each BMI group) is shown in each bar.

1 year after the fracture, 165 of the surviving 665 patients (25%) had not returned to independent living conditions. The rate of being able to live independently was higher in those with a BMI > 26 than in those with a lower BMI (). The unadjusted OR for independent living 1 year after the fracture in patients with BMI > 26 was 2.8 (95% CI: 1.5–5.2) compared to the group with BMI < 22, and it was 2.7 (95% CI: 1.4–5.0) compared to the group with BMI 22–26. BMI remained statistically significantly associated with independent living 1 year postoperatively, even after adjustment for age, sex, ASA score, and having shared housing upon admission ().

Table 3. The association between BMI and ability to live independently 1 year after hip fracture, adjusted for ASA score, shared housing, age, and sex using multivariate logistic regression analysis

Discussion

In this prospective study of 843 old hip fracture patients living independently and without severe cognitive impairment, overweight or obesity were associated with lower risk of death and a higher degree of independent living 1 year after the fracture. The mortality rate in geriatric patients in general has been considered to be higher in patients who are underweight, when defined, for example, as BMI ≤ 20 (Flodin et al. Citation2000, Weiss et al. Citation2008). We found increased 1-year mortality not only in those with BMI < 22, but also in those with BMI 22–26, compared to patients with BMI > 26. This has not been shown previously in hip fracture patients, although patients with a BMI of ≤ 20 and those with a BMI value in the lowest quartile have previously been reported to be at risk of increased mortality (Meyer et al. Citation1995, Juliebo et al. Citation2010). Consistent with our findings, a recent study on fracture patients in general, aged ≥ 40 years, showed that they had a reduced risk of death when overweight (BMI 25–29.9) or obese (BMI ≥ 30) compared to those with normal weight (BMI ≥ 18.5 but < 25) (Prieto-Alhambra et al. Citation2014). A similarly increased mortality rate has been seen in patients with BMI ≤ 24 undergoing cardiac valve surgery (Thourani et al. Citation2011); there was also a lower risk of dying in obese patients after primary shoulder arthroplasty (Singh et al. Citation2011). These observations have been referred to as “the obesity paradox”, indicating that in elderly patients, obesity is paradoxically associated with a lower—not higher—risk of death (Flegal et al. Citation2013). Our findings may indicate that a larger energy reserve is needed to meet the increased metabolic demands associated with trauma and postoperative catabolism after hip fracture, as in surgery procedures in general (Hebuterne et al. Citation2001, Ljungqvist et al. Citation2007).

The mean age and sex distributions in our study corresponded well with previous reports on hip fracture patients, so they were representative (Ponzer et al. Citation1999, Bachrach-Lindstrom et al. Citation2000). A substantial number of patients had low BMI, indicating risk of malnutrition in accordance with earlier reports (Hommel et al. Citation2007, Batsis et al. Citation2009, Hung et al. Citation2014). The overall 1-year mortality of 15% in the present study is lower than earlier reports of 22–29% (Haleem et al. Citation2008, Hommel et al. Citation2008). This may be explained by our selection of patients, which excluded those with severe cognitive impairment and residents of nursing homes before admission; these factors are well known to be associated with increased mortality (Hommel et al. Citation2008, Neuman et al. Citation2014, Tarazona-Santabalbina et al. Citation2015).

Advanced age, male sex, having comorbidities prior to fracture, pre-fracture level of functioning, a history of dementia, and living situation (alone or not) have been reported to influence the ability to live independently after a hip fracture (Aharonoff et al. Citation2004). No previous studies have shown that overweight and obesity is associated with a higher probability of living independently 1 year after a hip fracture. On the other hand, earlier reports have shown that low BMI and underweight in geriatric patients are risk factors for functional decline (Stuck et al. Citation1999). A low BMI in non-disabled but medically ill patients on admission to hospital has also been shown to be predictive of impaired ADL functioning at the time of discharge (Volpato et al. Citation2007), so it very likely affects the ability to live independently.

Our study had some limitations. We found a statistically significant association between BMI and mortality, but since this was an observational study it is not possible to infer causality. Our inclusion criteria limit the generalizability of our results, because a large proportion of hip fracture patients suffer from dementia and come from nursing homes. However, since patients with hip fracture are highly heterogeneous, we chose to exclude those with severe cognitive impairment and those who were nursing home residents, to obtain a more homogeneous group of healthier patients, living independently. Earlier studies have already shown that survival and functional outcomes are poor after hip fracture in patients suffering from severe cognitive impairment and in those who are nursing home residents (Tarazona-Santabalbina et al. Citation2015, Neuman et al. Citation2014). Low BMI has already been reported to be more common in patients with hip fracture in general than in aged-matched controls. Our purpose was to determine whether this also corresponded to a group of “healthier” hip fracture patients, and also to determine how BMI in this group related to outcome.

We used the SPMSQ to detect the presence of cognitive dysfunction, a symptom seen in both dementia and temporary impairment. Fluctuation in cognitive function upon admission for hip fracture has previously been shown to be more pronounced in patients with mild or moderate cognitive impairment than in patients with severe cognitive impairment or intact cognition (Strömberg et al. Citation1997). An SPMSQ score of ≥ 3 correct answers was one of the inclusion criteria of the study, which made exclusion of patients with temporary impairment less likely. The general physical status of the patients was assessed according to the ASA classification, which as a comorbidity index has been shown to predict mortality in hip fracture patients (Bjorgul et al Citation2010). In addition to ASA score, we also recorded the number of comorbidities to describe the current health status of each patient. Also, one limitation of our study was that BMI does not give any detailed information on body composition such as the distribution or ratio of lean and fat mass; these are factors that may influence outcome. Furthermore, BMI was only registered at baseline, and therefore weight change over time was not followed. The strength of our study was the prospective design with a large number of consecutively included patients; the novelty was the focus on studying a group of relatively healthy elderly hip fracture patients.

Our findings highlight the importance of finding interventions to prevent further weight loss postoperatively in hip fracture patients, many of whom are in a catabolic situation up to 1 year after the fracture (Hedstrom et al. Citation2006). However, the benefit of nutritional supplementation following hip fracture has not been conclusively demonstrated, which may be due to inadequate sample size and methodological problems—as reported in a Cochrane Collaboration Review of 20 randomized trials (Avenell and Handoll Citation2010). That review concluded that nutritional supplementation may have beneficial effects, such as reducing general complications and length of stay. Only 1 trial that evaluated the use of dietetic assistants (food choice, supplements, and assistance with feeding at meal times) showed a trend of lower mortality at 4 months in the intervention group compared to the controls who received usual care (Duncan et al. Citation2006). Another study showed that muscle mass was protected from catabolism after hip fracture only when protein supplementation was combined with an anabolic drug (Tidermark et al. Citation2004).

In summary, overweight and obese patients had a higher1-year survival rate and returned to independent living to a higher degree than those who were of normal or low weight. Thus, elderly patients with a hip fracture may benefit from being overweight, but the underlying mechanisms are unclear.

LF, AL, and MH: study design, data analysis, and writing and editing of the manuscript. TC and JL: data analysis and writing and editing of the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

We thank the Stockholm Hip Fracture Group. Financial support was provided by Karolinska Institutet funding and through the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet.

- Aharonoff G B, Barsky A, Hiebert R, Zuckerman J D, Koval K J. Predictors of discharge to a skilled nursing facility following hip fracture surgery in New York State. Gerontology 2004; 50 (5): 298–302.

- Avenell A, Handoll HH. Nutritional supplementation for hip fracture aftercare in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (Online) 2010 (1). Available from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/cochranelibrary/search

- Bachrach-Lindstrom M A, Ek A C, Unosson M. Nutritional state and functional capacity among elderly Swedish people with acute hip fracture. Scand J Caring Sci 2000; 14 (4): 268–74.

- Batsis J A, Huddleston J M, Melton L J t, Huddleston P M, Lopez-Jimenez F, Larson D R, et al. Body mass index and risk of adverse cardiac events in elderly patients with hip fracture: a population-based study. J Am Geriatr Sci 2009; 57 (3): 419–26.

- Bjorgul K, Novicoff W M, Saleh K J. American Society of Anesthesiologist Physical Status score may be used as a comorbidity index in hip fracture surgery. J Arthroplasty 2010; 25(6Suppl): 134–7.

- Dey D K, Rothenberg E, Sundh V, Bosaeus I, Steen B. Height and body weight in the elderly. A 25-year longitudinal study of a population aged 70 to 95 years. Eur J Clin Nutr 1999; 53 (12): 905–14.

- Duncan D G, Beck S J, Hood K, Johansen A. Using dietetic assistants to improve the outcome of hip fracture: a randomised controlled trial of nutritional support in an acute trauma ward. Age Ageing; 2006; 35 (2):148–53.

- Eiben G, Dey D K, Rothenberg E, Steen B, Björkelund C, Bengtsson C, Lissner L. Obesity in 70-year Swedes: Secular changes over 30 years. Int J Obes 2005; 25 (7): 810–17.

- Fiatarone Singh M A, Singh N A, Hansen R D, Finnegan T P, Allen B J, Diamond T H, et al. Methodology and baseline characteristics for the Sarcopenia and Hip Fracture study: a 5-year prospective study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2009; 64 (5): 568–74.

- Flegal K M, Kit B K, Orpana H, Graubard B I. Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2013; 309 (1): 71–82.

- Flodin L, Svensson S, Cederholm T. Body mass index as a predictor of 1 year mortality in geriatric patients. Clin Nutr 2000; 19 (2): 121–5.

- Haglund R M, Schuckit M A. A clinical comparison of tests of organicity in elderly patients. J Gerontol 1976; 31: 654–9.

- Haleem S, Lutchman L, Mayahi R, Grice J E, Parker M J. Mortality following hip fracture: trends and geographical variations over the last 40 years. Injury 2008; 39 (10): 1157–63.

- Hebuterne X, Bermon S, Schneider S M. Ageing and muscle: the effects of malnutrition, re-nutrition, and physical exercise. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2001; 4 (4): 295–300.

- Hedstrom M, Saaf M, Dalen N. Low IGF-I levels in hip fracture patients. A comparison of 20 coxarthrotic and 23 hip fracture patients. Acta Orthop Scand 1999; 70 (2): 145–8.

- Hedstrom M, Ljungqvist O, Cederholm T. Metabolism and catabolism in hip fracture patients: nutritional and anabolic intervention–a review. Acta Orthop 2006; 77 (5): 741–7.

- Hommel A, Bjorkelund K B, Thorngren K G, Ulander K. Nutritional status among patients with hip fracture in relation to pressure ulcers. Clin Nutr 2007; 26 (5): 589–96.

- Hommel A, Ulander K, Bjorkelund K B, Norrman P O, Wingstrand H, Thorngren K G. Influence of optimised treatment of people with hip fracture on time to operation, length of hospital stay, reoperations and mortality within 1 year. Injury 2008; 39 (10): 1164–74.

- Hung L W, Tseng W J, Huang G S, Lin J. High short-term and long-term excess mortality in geriatric patients after hip fracture: a prospective cohort study in Taiwan. BMC Musculoskel Disord 2014; 15: 151.

- Hutagalung R, Marques J, Kobylka K, Zeidan M, Kabisch B, Brunkhorst F, et al. The obesity paradox in surgical intensive care unit patients. Intensive Care Med 2011; 37 (11): 1793–9.

- Juliebo V, Krogseth M, Skovlund E, Engedal K, Wyller T B. Medical treatment predicts mortality after hip fracture. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2010; 65 (4): 442–9.

- Katz S, Ford A B, Moskowitz R W, Jackson B A, Jaffe M W. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 1963; 185: 914–9.

- Ljungqvist O, Soop M, Hedstrom M. Why metabolism matters in elective orthopedic surgery: a review. Acta Orthop 2007; 78 (5): 610–5.

- Meyer H E, Tverdal A, Falch J A. Body height, body mass index, and fatal hip fractures: 16 years’ follow-up of 674,000 Norwegian women and men. Epidemiology 1995; 6 (3): 299–305.

- Neuman M D, Silber J H, Magaziner J S, Passarella M A, Mehta S, Werner R M. Survival and functional outcomes after hip fracture among nursing home residents. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174 (8): 1273–80.

- Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1975; 23 (10): 433–41.

- Ponzer S, Tidermark J, Brismar K, Soderqvist A, Cederholm T. Nutritional status, insulin-like growth factor-1 and quality of life in elderly women with hip fractures. Clin Nutr 1999; 18 (4): 241–6.

- Prieto-Alhambra D, Premaor M O, Aviles F F, Castro A S, Javaid M K, Nogues X, et al. Relationship between mortality and BMI after fracture: a population-based study of men and women aged >/=40 years. J Bone Miner Res 2014; 29 (8): 1737–44.

- Singh J A, Sperling J W, Cofield R H. Ninety day mortality and its predictors after primary shoulder arthroplasty: an analysis of 4,019 patients from 1976-2008. BMC Musculoskel Disord 2011; 12: 231.

- Strömberg L, Lindgren U, Nordin C, Ohlen G, Svensson O. The appearance and disappearance of cognitive impairment in elderly patients during treatment for hip fracture. Scand J Caring Sci 1997; 11:167–75.

- Stuck A E, Walthert J M, Nikolaus T, Bula C J, Hohmann C, Beck J C. Risk factors for functional status decline in community-living elderly people: a systematic literature review. Soc Sci Med (1982) 1999; 48 (4): 445–69.

- Sullivan D H, Sun S, Walls R C. Protein-energy undernutrition among elderly hospitalized patients: a prospective study. JAMA 1999; 281 (21): 2013–9.

- Tarazona-Santabalbina F J, Belenguer-Varea A, Rovira Daudi E, Salcedo Mahiques E, Cuesta Peredo D, Domenech-Pascual J R, et al. Severity of cognitive impairment as a prognostic factor for mortality and functional recovery of geriatric patients with hip fracture. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2015; 15 (3): 289–95

- Tidermark J, Ponzer S, Carlsson P, Söderqvist A, Brismar K, Tengstrand B, Cederholm T. Effects of protein-rich supplementation and nandrolone in lean elderly women with femoral neck fractures. Clin Nutr 2004; 23 (4):587–596.

- Thourani V H, Keeling W B, Kilgo P D, Puskas J D, Lattouf O M, Chen E P, et al. The impact of body mass index on morbidity and short- and long-term mortality in cardiac valvular surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011; 142 (5): 1052–61.

- Weiss A, Beloosesky Y, Boaz M, Yalov A, Kornowski R, Grossman E. Body mass index is inversely related to mortality in elderly subjects. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23 (1): 19–24.

- Volpato S, Onder G, Cavalieri M, Guerra G, Sioulis F, Maraldi C, et al. Characteristics of nondisabled older patients developing new disability associated with medical illnesses and hospitalization. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22 (5): 668–74.