Abstract

Background and purpose — Surgery for metastases of renal cell carcinoma has increased in the last decade. It carries a risk of massive blood loss, as tumors are hypervascular and the surgery is often extensive. Preoperative embolization is believed to facilitate surgery. We evaluated the effect of preoperative embolization and resection margin on intraoperative blood loss, operation time, and survival in non-spinal skeletal metastases of renal cell carcinoma.

Patients and methods — This retrospective study involved 144 patients, 56 of which were treated preoperatively with embolization. The primary outcome was intraoperative blood loss. We also identified factors affecting operating time and survival.

Results — We did not find statistically significant effects on intraoperative blood loss of preoperative embolization of skeletal non-spinal metastases. Pelvic localization and large tumor size increased intraoperative blood loss. Marginal resection compared to intralesional resection, nephrectomy, level of hemoglobin, and solitary metastases were associated with better survival.

Interpretation — Tumor size, but not embolization, was an independent factor for intraoperative blood loss. Marginal resection rather than intralesional resection should be the gold standard treatment for skeletal metastases in non-spinal renal cell carcinoma, especially in the case of a solitary lesion, as this improved the overall survival.

The incidence of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has been increasing (Engholm et al. Citation2010). RCC is characterized by an absence of early warning signs, especially since small tumors rarely produce symptoms. Thus, diagnosis can be delayed until the disease has metastasized (Motzer et al. Citation1996). The lung and bone are the most common sites for metastases (Han et al. Citation2003). Studies have shown that 30–40% of patients either have bone metastases at initial presentation of disease or they develop these later (Schlesinger-Raab et al. Citation2008, Woodward et al. Citation2011). New therapeutic options such as multimodal-targeted therapies have improved the treatment of RCC (Motzer et al. Citation2009). Medical therapy and radiotherapy are the first-line treatments for metastatic RCC. However, as metastases of RCC are relatively resistant to these treatments, surgery may be considered for skeletal metastases (Hwang et al. Citation2014). Indications for surgery with local tumor control are severe pain, restricted function, and impending or pathological fracture. According to a recent study, the proportion of patients with metastatic RCC who receive surgical therapy has increased from 4% to 6% in the last decade (Antczak et al. Citation2014).

The 5-year survival in RCC has been reported to be 77–92% for non-metastatic disease (Ito et al. Citation2015), decreasing to 21% after diagnosis of metastases (Schlesinger-Raab et al. Citation2008). The 5-year survival rate after the first operation for bone metastasis is 11% (Lin et al. Citation2007). There have been several studies on factors that affect survival after metastatic bone disease. In general, nephrectomy, the absence of visceral metastases, and solitary bone metastases improve survival (Toyoda et al. 2007, Yuasa et al. 2011, Hwang et al. Citation2014). Resection of a solitary skeletal lesion with a tumor-free margin appears to increase the survival rate (Baloch et al. Citation2000, Jung et al. Citation2003, Ratasvuori et al. Citation2014).

Surgical treatment of skeletal metastases from RCC carries a risk of massive blood loss, as tumors are hypervascular and the surgery is often extensive (Wilson et al. Citation2010, Robial et al. Citation2012). Preoperative embolization is often used; most authors agree that this reduces intraoperative blood loss substantially, making surgery easier and facilitating radical removal (Chatziioannou et al. Citation2000, Wirbel et al. Citation2005, Nair et al. Citation2013, Pazionis et al. Citation2014). Preoperative embolization in spinal RCC metastases is performed frequently, despite inconsistent effect (Wilson et al. Citation2010, Robial et al. Citation2012, Thiex et al. Citation2013, Quraishi et al. Citation2013, Clausen et al. Citation2015). Similarly, there is no consensus regarding non-spinal metastases. Some studies support the belief that preoperative embolization reduces intraoperative blood loss (Chatziioannou et al. Citation2000, Wirbel et al. Citation2005). Other authors have suggested that feeding vessels that are clearly identified during operation are easily ligated (Baloch et al. Citation2000, Lin et al. Citation2007). However, most of these studies have included only a few patients.

We therefore determined the effect of preoperative embolization and resection margin on intraoperative blood loss and operating time in a large cohort of patients suffering from RCC with non-spinal skeletal metastases. We also investigated factors that influence postoperative survival.

Patients and methods

Patients were identified from prospectively maintained databases at 4 Nordic bone tumor centers (Aarhus, Denmark; Bergen, Norway; Stockholm, Sweden; and Tampere, Finland). All the patients had had surgery for non-spinal skeletal metastases from RCC between October 1999 and June 2014. Metastatic RCC was confirmed histologically. Patient demographics included: age at presentation of pathological fracture, sex, comorbidities (diabetes and heart disease), American Society of Anesthesiologists classification, smoking habits, size (cm) and site of metastases (humerus, femur, pelvis), preoperative diagnostic procedures, hemoglobin value, number of skeletal metastases, and preoperative radiotherapy to the site of metastasis. Treatment of the primary tumor (including nephrectomy) and the presence of organ metastases were also recorded. Information on the surgical resection procedure for metastases, including margins of resection, methods of reconstruction, use of tourniquet, estimated intraoperative blood loss (IBL), and operating time, was taken from the anesthesia forms. Surgical margins were defined as being intralesional in cases where macroscopic tumor was left—as in nailing—or as being marginal in cases were margins were tumor-free. Details on the preoperative embolization procedure were recorded for each patient. There was no strict protocol for when to use preoperative embolization, but the size of the tumor was similar in embolized and non-embolized patients. If a patient underwent preoperative embolization, surgery was always performed within 72 h of the embolization.

Preoperative embolization was performed via ipsilateral or contralateral groin puncture. Feeding arteries (1–7 arteries) were accessed with microcatheters and occluded using various techniques, according to operator and institutional preferences. Detachable platinum coils, liquid embolization materials (acrylic glues), particles (polyvinyl alcohol), gelatin foam powder, or a combination of these methods were used. Most tumors were embolized with platinum coils, particles, or a combination of these. The success of the embolization was evaluated by comparing the pre-embolization and post-embolization angiography images after completion of the procedure. The interventional radiologist who performed the procedure evaluated and classified the degree of devascularization as adequate (approximating more than 75% tumor devascularization based on visual inspection of residual tumor enhancement), suboptimal (between 50% and 75% devascularization), or inadequate (less than 50% devascularization). We analyzed post-embolization and postoperative complications.

Statistics

The primary outcome of the study was intraoperative IBL. The amount of intraoperative IBL was not normally distributed, so logarithmic transformation was used. The variables used in the analyses included the surgical resection margin, preoperative embolization, tumor size, operating time, patient age, comorbidities, preoperative hemoglobin value, operative method, and site of metastases. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to evaluate differences between the groups with or without embolization. The operating time was also considered to be a dependent factor. Patient survival was assessed using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test, and Cox regression analysis was used to identify independent factors affecting survival. The patients for whom the date of death was missing—either because the patient was still alive or had been lost to follow-up—were censored at the last time they were known to be alive. If the reason for death was not cancer, the case was censored. Proportional hazards assumption was taken into account. All the variables were checked with Kaplan-Meier curves. We plotted the cumulative hazards functions for the covariates and checked that lines did not cross each other. Statistical significance was assumed with p-values less than 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 20.0.

Results

There were 148 operations in 144 patients, 99 male and 45 female, with a mean age of 67 (40–90) years at first operation of bone metastasis. 56 of the 148 tumors (38%) were embolized preoperatively. Baseline data for patients with and without embolization were similar (). Adequate post-embolization results were achieved in 46 cases, suboptimal results in 9 cases, and an inadequate result in 1 case ().

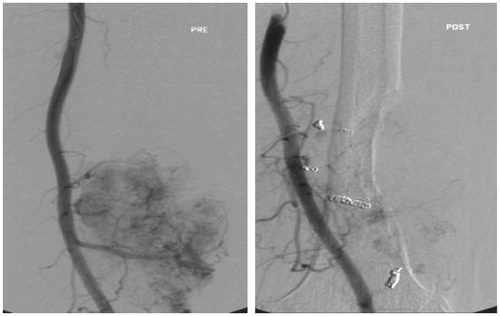

Figure 1. Preoperative embolization performed on a tumor measuring 13 cm located in the distal femur. Since only some residual peripheral tumor enhancement was seen, this was considered to be an adequate embolization outcome. A marginal resection and endoprosthetic replacement resulted in an IBL of 1.3

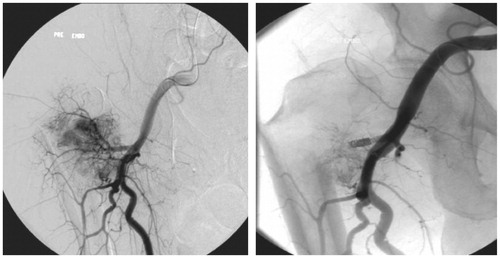

Figure 2. Preoperative embolization performed on a tumor with fracture in the proximal femur measuring 9 cm. Since a clear region of tumor enhancement (about 40% of the tumor) was seen in the lower parts of the tumor, this was considered to be a suboptimal embolization result. An intralesional resection and endoprosthetic replacement resulted in an IBL of 0.2 L.

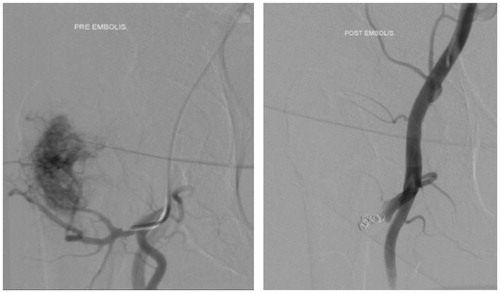

Figure 3. Preoperative embolization performed on a proximal femur tumor measuring 5 cm. In the absence of any tumor enhancement, this was classified as an adequate embolization result. Intralesional resection and endoprosthetic replacement resulted in an IBL of 0.5 L.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients with and without preoperative embolization for skeletal metastases from RCC

There were 140 patients, 86 without embolization and 54 with embolization, with information on IBL. Pelvic location (Mann-Whitney U-test, p < 0.01) and increasing tumor size (p < 0.01) were associated with increased IBL. There were no interactions between these variables. Factors such as age, liver metastasis, overall metastatic load, solitary skeletal metastasis, preoperative hemoglobin value, use of a tourniquet, operating time, operation method, resection margin, and preoperative embolization (including adequate cases) had no apparent effect on IBL (). Embolization did not have a statistically significant positive effect on operating time (Table 3, see Supplementary data). Operating time was significantly shorter with no embolization for tumors in the humerus.;13)

Table 2. A comparison of the factors affecting intraoperative blood loss (IBL) in the different subgroups of cases with and without preoperative embolization, performed using the Mann-Whitney U-test

There were no procedure-related complications during or after embolization. Postoperative complications were reported in 23 cases (16%), including tumor progression (4), nerve damage (1), nail failures (3), massive blood loss (1), prosthetic dislocations (2), wound healing problems (5), non-unions (2), pulmonary embolisms (3), and deep venous thrombosis (1). The embolization procedure did not predispose patients to complications.

The median postoperative survival was 13 (0–150) months. Marginal resection rather than intralesional resection, solitary skeletal metastasis, the absence of organ metastases, a hemoglobin level over 100 g/L, and nephrectomy were associated with better survival rates, but age, tumor size, tumor location, IBL, and preoperative embolization were not (Table 4, see Supplementary data). In the Cox model, solitary metastasis, marginal resection, hemoglobin level over 100 g/L, and nephrectomy were independently associated with better survival rates ().

Table 5. Factors associated with survival (Cox regression analysis)

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we could not find statistically significant effects of preoperative embolization of skeletal non-spinal metastases on intraoperative blood loss, irrespective of whether or not there was an adequate embolization result. This contrasts with several studies that have advocated preoperative embolization of bone metastases from RCC as an effective procedure for minimization of intraoperative bleeding (Olerud et al. Citation1993, Barton et al. Citation1996, Chatziioannou et al. Citation2000). By contrast, 1 study found greater IBL in embolized patients but suggested that this was because of patient selection bias, since embolization was used in larger, more central tumors and at sites where a tourniquet could not be applied to control IBL (Lin et al. Citation2007). In our study, tourniquet use did not have any apparent effect on IBL and the tumors in the embolized and non-embolized groups were similar in both size and location.

The studies that have shown any effect of embolization on reducing IBL have had several limitations, including small numbers of patients and the use of statistical methods that were not sensitive to selection bias. Except for its large number of patients, the present study also had similar limitations, including the retrospective design and the possibility of selection bias. There may have been selection bias due to the different medical treatments, which varied considerably, making the numbers of patients in different treatment categories too small for meaningful statistical analysis. There may also have been bias in selecting the types of surgical procedures, in selecting patients for preoperative embolization, and in the different embolization methods. The strength of our study lies in the number of patients: to date, this is the largest published series of patients with non-spinal RCC metastases to be treated surgically with preoperative embolization.

There was a significant correlation between tumor size and IBL irrespective of whether or not there was embolization. This has also been reported in previous studies. Pazionis et al. (Citation2014) found a correlation between tumor size and IBL and operating time. In their case-control study, the association between embolization and reduced blood loss was only seen in femoral procedures, but in a multivariable analysis, tumor size was the only significant factor affecting IBL. In our study, pelvic location was found to be a statistically significant predictor of excessive blood loss, and was probably associated with tumor size because pelvic metastases tended to be larger.

Although IBL is a commonly used outcome measure in evaluation of the efficacy of preoperative embolization, the amount of bleeding is difficult to quantify and may not be an optimal measure for evaluation of the benefits of embolization. Although we adjusted for several confounding factors including resection margin, location of the metastases, and operation method, we did not find any statistically significant differences in IBL between cases with embolization or cases without. No benefit of preoperative embolization in facilitating the operative treatment has been convincingly shown. In our study, preoperative embolization did not reduce operating time—irrespective of the location of the tumor or the method of operation.

Embolization is believed to be a safe procedure. In a study involving 228 embolizations of a variety of tumors, only 1 case with a large groin hematoma and 1 cardiac arrest due to general anesthesia were reported (Nair et al. Citation2013). In our study, there were no major complications related to the embolization procedures. Although embolization is a safe procedure, it is invasive, time-consuming, and expensive. Because we found similar operating times, IBL, and survival between groups with or without embolization, we do not recommend it as a routine procedure. Further research may help to define specific patient groups that might benefit from embolization. Also, the use of embolization for pain control requires further investigation.

Our study confirms the results of previous studies that have demonstrated improved survival with a tumor-free margin of a metastatic lesion in RCC (Baloch et al. Citation2000, Lin et al. Citation2007, Fottner et al. Citation2010). In the present study, several confounding factors such as age, tumor size, and operation method were also taken into account. Even though radiotherapy of skeletal metastases can be used for pain control (Reichel et al. Citation2007), surgery is more effective in restoring function and in preventing local tumor progression (Laitinen et al. Citation2015). Moreover, the metastatic pattern with solitary skeletal metastasis, type of surgery with a tumor-free margin, and prosthetic replacement substantially influence the overall patient and reconstruction survival after surgery for RCC metastases (Jung et al. Citation2003, Fuchs et al. Citation2005, Alt et al. Citation2011, Laitinen et al. Citation2015). In the present study, there were 12 cases in which marginal resection was done even though patients had multiple skeletal metastases. Even in this limited group, marginal resection resulted in significantly better survival than an intralesional resection. The role of nephrectomy in patients with disseminated disease is debatable. It has been reported that nephrectomy increases survival in patients with skeletal metastases (Evenski et al. Citation2012). This could not be analyzed in our material because of the number of patients in appropriate subgroups being too small. However, since our data show that marginal resection improves survival both in patients with solitary metastasis and in those with multiple skeletal metastases, we recommend that in RCC with skeletal metastases, a marginal and not an intralesional resection should be aimed for.

In conclusion, we were unable to show any benefit of preoperative embolization in preventing intraoperative bleeding and in improving surgical or oncological outcome. A select group of patients may benefit from preoperative embolization, especially if the metastatic lesion is located in the pelvis. This should be addressed in future investigations. In order to improve overall survival, marginal resection—and not intralesional resection—should be the gold standard for surgical management of skeletal metastases in RCC, especially if there are solitary lesions.

and 4 is available on the Acta Orthopaedica website at www.actaorthopaedica.org, identification number 9216.

MR and ML designed the study. MR, ML, RW, BHH, and CT participated in data collection. MR performed the statistical analysis, wrote the first draft, and took care of manuscript revisions. NS offered expert comments on the embolization procedures. All the authors contributed to preparation of the manuscript.

We are grateful for financial support of this study by the Competitive Research Funding of Tampere University Hospital and by the Cancer Society of Finland. Special thanks to Heini Huhtala, our epidemiologist at Tampere University, for sharing her expertise in the statistical analyses and methods used in this study.

No competing interests declared.

- Alt A L, Boorjian S A, Lohse C M, Costello B A, Leibovich B C, Blute M L. Survival after complete surgical resection of multiple metastases from renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 2011; 117 (13): 2873–82.

- Antczak C, Trinh V Q, Sood A, Ravi P, Roghmann F, Trudeau V, Chang S L, Karakiewicz P I, Kibel A S, Krishna N, Nguyen P L, Saad F, Sammon J D, Sukumar S, Zorn K C, M Sun, Trinh Q D. The health care burden of skeletal related events in patients with renal cell carcinoma and bone metastasis. J Urol 2014; 191 (6): 1678–84.

- Baloch K G, Grimer R J, Carter S R, Tillman R M. Radical surgery for the solitary bony metastasis from renal-cell carcinoma. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000; 82 (1): 62–7.

- Barton P P, Waneck R E, Karnel F J, Ritschl P, Kramer J, Lechner G L. Embolization of bone metastases. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1996; 7 (1): 81–8.

- Chatziioannou A N, Johnson M E, Pneumaticos S G, Lawrence D D, Carrasco C H. Preoperative embolization of bone metastases from renal cell carcinoma. Eur Radiol 2000; 10 (4): 593–6.

- Clausen C, Dahl B, Frevert S C, Hansen L V, Nielsen M B, Lonn L. Preoperative embolization in surgical treatment of spinal metastases: single-blind, randomized controlled clinical trial of efficacy in decreasing intraoperative blood loss. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2015; 26 (3): 402–12 e1.

- Engholm G, Ferlay J, Christensen N, Bray F, Gjerstorff M L, Klint A, Kotlum J E, Olafsdottir E, Pukkala E, Storm H H. NORDCAN–a Nordic tool for cancer information, planning, quality control and research. Acta Oncol 2010; 49 (5): 725–36.

- Evenski A, Ramasunder S, Fox W, Mounasamy V, Temple H T. Treatment and survival of osseous renal cell carcinoma metastases. J Surg Oncol 2012; 106 (7): 850–5.

- Fottner A, Szalantzy M, Wirthmann L, Stahler M, Baur-Melnyk A, Jansson V, Durr H R. Bone metastases from renal cell carcinoma: patient survival after surgical treatment. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010; 11: 145.

- Fuchs B, Trousdale R T, Rock M G. Solitary bony metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: significance of surgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005; (431): 187–92.

- Han K R, Pantuck A J, Bui M H, Shvarts O, Freitas D G, Zisman A, Leibovich B C, Dorey F J, Gitlitz B J, Figlin R A, Belldegrun A S. Number of metastatic sites rather than location dictates overall survival of patients with node-negative metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urology 2003; 61 (2): 314–9.

- Hwang N, Nandra R, Grimer R J, Carter S R, Tillman R M, Abudu A, Jeys L M. Massive endoprosthetic replacement for bone metastases resulting from renal cell carcinoma: factors influencing patient survival. Eur J Surg Oncol 2014; 40 (4): 429–34.

- Ito N, Kojima S, Teramukai S, Mikami Y, Ogawa O, Kamba T. Outcomes of curative nephrectomy against renal cell carcinoma based on a central pathological review of 914 specimens from the era of cytokine treatment. Int J Clin Oncol 2015; [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1007/s10147-015-0840-5.

- Jung S T, Ghert M A, Harrelson J M, Scully S P. Treatment of osseous metastases in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003; (409): 223–31.

- Laitinen M, Parry M, Ratasvuori M, Wedin R, Albergo J I, Jeys L, Abudu A, Carter S, Gaston L, Tillman R, Grimer R. Survival and complications of skeletal reconstructions after surgical treatment of bony metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2015; 41(7): 886–92.

- Lin P P, Mirza A N, Lewis V O, Cannon C P, Tu S M, Tannir N M, Yasko A W. Patient survival after surgery for osseous metastases from renal cell carcinoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89 (8): 1794–801.

- Motzer R J, Bander N H, Nanus D M. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1996; 335 (12): 865–75.

- Motzer R J, Hutson T E, Tomczak P, Michaelson M D, Bukowski R M, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik C, Pili R, Bjarnason G A, Garcia-del-Muro X, Sosman J A, Solska E, Wilding G, Thompson J A, Kim S T, Chen I, Huang X, Figlin R A. Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27 (22): 3584–90.

- Nair S, Gobin Y P, Leng L Z, Marcus J D, Bilsky M, Laufer I, Patsalides A. Preoperative embolization of hypervascular thoracic, lumbar, and sacral spinal column tumors: technique and outcomes from a single center. Interv Neuroradiol 2013; 19 (3): 377–85.

- Olerud C, Jonsson H, Jr, Lofberg A M, Lorelius L E, Sjostrom L. Embolization of spinal metastases reduces peroperative blood loss. 21 patients operated on for renal cell carcinoma. Acta Orthop Scand 1993; 64 (1): 9–12.

- Pazionis T J, Papanastassiou I D, Maybody M, Healey J H. Embolization of hypervascular bone metastases reduces intraoperative blood loss: a case-control study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472 (10): 3179–87.

- Quraishi N A, Purushothamdas S, Manoharan S R, Arealis G, Lenthall R, Grevitt M P. Outcome of embolised vascular metastatic renal cell tumours causing spinal cord compression. Eur Spine J 2013; 22Suppl1: S27–32.

- Ratasvuori M, Wedin R, Hansen B H, Keller J, Trovik C, Zaikova O, Bergh P, Kalen A, Laitinen M. Prognostic role of en-bloc resection and late onset of bone metastasis in patients with bone-seeking carcinomas of the kidney, breast, lung, and prostate: SSG study on 672 operated skeletal metastases. J Surg Oncol 2014; 110 (4): 360–5.

- Reichel L M, Pohar S, Heiner J, Buzaianu E M, Damron T A. Radiotherapy to bone has utility in multifocal metastatic renal carcinoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007; 459: 133–8.

- Robial N, Charles Y P, Bogorin I, Godet J, Beaujeux R, Boujan F, Steib J P. Is preoperative embolization a prerequisite for spinal metastases surgical management? Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2012; 98 (5): 536–42.

- Schlesinger-Raab A, Treiber U, Zaak D, Holzel D, Engel J. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a population-based study with 25 years follow-up. Eur J Cancer 2008; 44 (16): 2485–95.

- Thiex R, Harris M B, Sides C, Bono C M, Frerichs K U. The role of preoperative transarterial embolization in spinal tumors. A large single-center experience. Spine J 2013; 13 (2): 141–9.

- Wilson M A, Cooke D L, Ghodke B, Mirza S K. Retrospective analysis of preoperative embolization of spinal tumors. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010; 31 (4): 656–60.

- Wirbel R J, Roth R, Schulte M, Kramann B, Mutschler W. Preoperative embolization in spinal and pelvic metastases. J Orthop Sci 2005; 10 (3): 253–7.

- Woodward E, Jagdev S, McParland L, Clark K, Gregory W, Newsham A, Rogerson S, Hayward K, Selby P, Brown J. Skeletal complications and survival in renal cancer patients with bone metastases. Bone 2011; 48 (1): 160–6.